ideas

There are notes and notes, of course: notes to oneself and notes to others; notes taken, made, jotted, and passed. Mash, doctor’s, suicide, and condolence notes. Field, class, and case notes; notes for general circulation; foot and head notes, notes of hand. But it’s the bookish notes that academics care most about, the ones that intervene between the things we read and the things we write. […]

In his 1689 De arte Excerpendi, the Hamburg rhetorician Vincent Placcius described a scrinium literatum, or literary cabinet, whose multiple doors held 3,000 hooks on which loose slips could be organized under various headings and transposed as necessary. Two of the cabinets were eventually built, one for Placcius’s own use and one acquired by Leibniz. It was an early manifestation of the principle that still governs our response to the knowledge explosion: The remedy for the problems created by information technology is more information technology. […]

There’s no evidence that Leibniz made any use of his literary cabinet. Despite his lifelong interest in organizational schemes—he designed one of the earliest book-indexing systems—Leibniz’s note-taking was as disorganized as it was obsessive.

{ Geoffrey Nunberg/The Chronicle of Higher Education | Continue reading }

flashback, ideas | January 10th, 2013 3:51 am

Age-otori (Japanese): To look worse after a haircut

Tingo (Pascuense language of Easter Island): To borrow objects one by one from a neighbor’s house until there is nothing left

Backpfeifengesicht (German): A face badly in need of a fist

{ via The Atlantic | Continue reading }

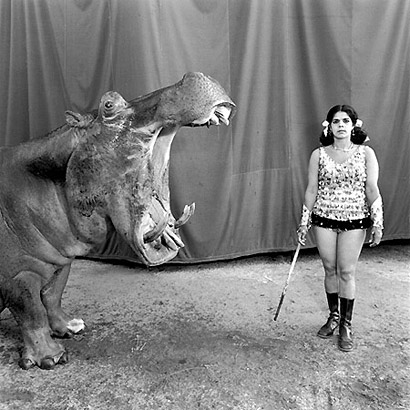

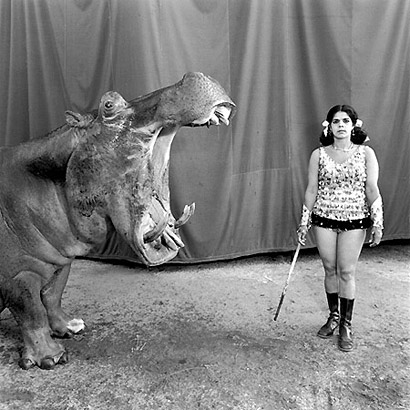

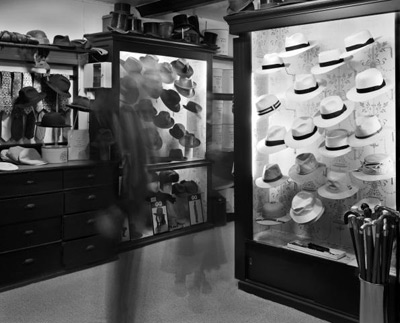

photo { Mary Ellen Mark }

Linguistics, within the world | January 9th, 2013 3:19 pm

The mystery of the art market is that some people would rather possess an object of marginal utility than the ultra-usable money they exchange for it. This is the mystery of all markets in which taste is transformed into appetite by a nonpecuniary cloud of discourse that surrounds the negotiation. There is always a tipping point at which one’s taste for Picasso or freedom or pinot noir becomes a necessity, or at least something one would rather not do without. The exact nature of this “something” is effervescent and indistinct.

{ Dave Hickey | Continue reading }

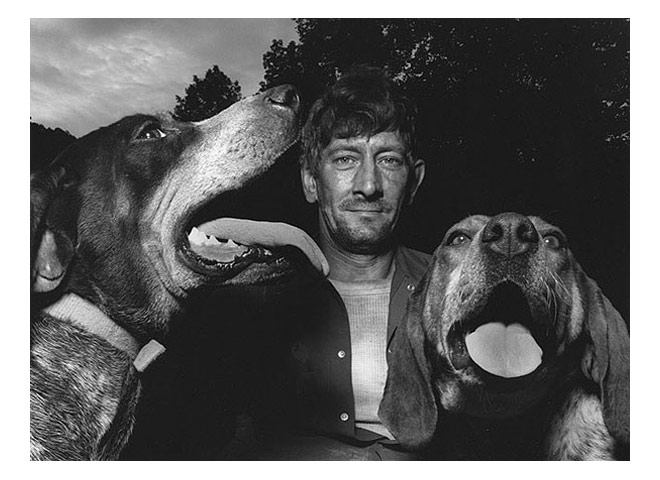

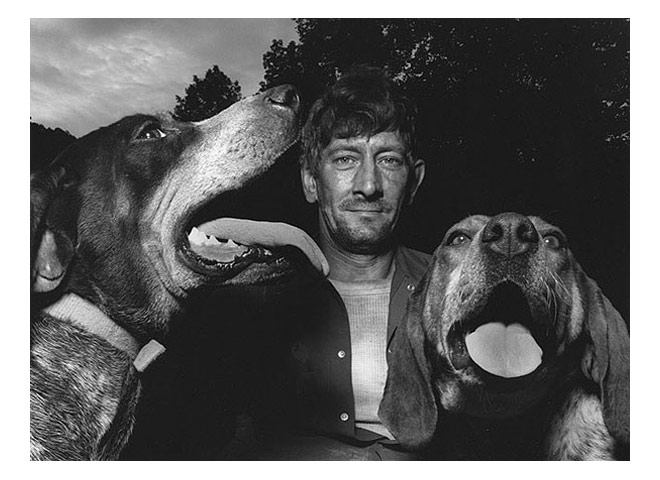

photo { Shelby Lee Adams }

art, economics, ideas, photogs | January 7th, 2013 2:16 pm

Slowly, but surely, robots (and virtual ’bots that exist only as software) are taking over our jobs; according to one back-of-the-envelope projection, in ninety years “70 percent of today’s occupations will likewise be replaced by automation.” […]

If history repeats itself, robots will replace our current jobs, but, says Kelly, we’ll have new jobs, that we can scarcely imagine:

In the coming years robot-driven cars and trucks will become ubiquitous; this automation will spawn the new human occupation of trip optimizer, a person who tweaks the traffic system for optimal energy and time usage. Routine robosurgery will necessitate the new skills of keeping machines sterile. When automatic self-tracking of all your activities becomes the normal thing to do, a new breed of professional analysts will arise to help you make sense of the data.

Well, maybe. Or maybe the professional analysts will be robots (or least computer programs), and ditto for the trip optimizers and sterilizers.

{ The New Yorker | Continue reading }

economics, future, ideas, robots & ai | January 1st, 2013 11:24 am

Perhaps no other human trait is as variable as human height. […] The source of that variation is something that anthropologists have been trying to root out for decades. Diet, climate and environment are frequently linked to height differences across human populations.

More recently, researchers have implicated another factor: mortality rate. In a new study in the journal Current Anthropology, Andrea Bamberg Migliano and Myrtille Guillon, both of the University College London, make the case that people living in populations with low life expectancies don’t grow as tall as people living in groups with longer life spans.

{ Smithsonian | Continue reading }

science, theory | December 27th, 2012 3:22 pm

Two recent articles in TiGS by Gerald Crabtree float the notion that we, as a species, are gradually declining in average intellect because we are accumulating mutations that deleteriously affect brain development or function. The observations that prompted this view seem to be: (i) intellectual disability can be caused by mutations in any one of a very large number of genes; and (ii) de novo mutations arise at a low but steady rate in every new egg or sperm. He further proposes that (iii) genes involved in brain development or function are especially vulnerable to the effects of such mutations. Considered in isolation, these could reasonably lead to the conclusion that mutations reducing intelligence must be constantly accumulating in the human gene pool. Thankfully, these factors do not act in isolation.

If we, as a species, were simply constantly accumulating new mutations, then one would predict the gradual degradation of every aspect of fitness over time, not just intelligence. Indeed, life could simply not be sustained over evolutionary time in the face of such genetic entropy. Fortunately (for the species, although not for all individual members), natural selection is an attentive minder. […]

Whether causally or as a correlated indicator, intelligence is strongly associated with evolutionary fitness, even in current societies. The threat posed by new mutations to the intellect of the species is therefore kept in check by the constant vigilance of selection. Thus, despite ready counter-examples from nightly newscasts, there is no scientific reason to think that we humans are on an inevitable genetic trajectory towards idiocy.

{ Cell | Continue reading }

genes, ideas, science | December 18th, 2012 2:23 pm

We have past, present and future; we can imagine various time relationships such as imagining some time in the future from the prospective of looking back at it from even further into the future. But we can also abandon identifying a particular time when we imagine. For example we can simulate what it would be like to be in another’s shoes or what it would be like to be in a different place. Instead of time-traveling, we can space-travel or identity-travel. It seems that the evidence so far implies that future and atemporal imagined events are represented similarly. But there are differences between temporal and atemporal imaginings.

{ thoughts on thoughts | Continue reading }

neurosciences, time | December 14th, 2012 2:00 am

We live in an image society. Since the turn of the 20th century if not earlier, Americans have been awash in a sea of images – in advertisements, in newspapers and magazines, on billboards, throughout the visual landscape. We are highly attuned to looks, first impressions and surface appearances, and perhaps no image is more seductive to us than our own personal image. In 1962, the cultural historian Daniel Boorstin observed that when people talked about themselves, they talked about their images. If the flourishing industries of image management — fashion, cosmetics, self-help — are any indication, we are indeed deeply concerned with our looks, reputations, and the impressions that we make. For over a hundred years, social relations and conceptions of personal identity have revolved around the creation, projection, and manipulation of images. […]

In what follows, I want to contemplate one legal consequence of the advent of the image society: the evolution of an area of law that I describe as the tort law of personal image. By the 1950s, a body of tort law – principally the privacy, defamation, publicity, and emotional distress torts4 — had developed to protect a right to control one’s own image, and to be compensated for emotional and dignitary harms caused by egregious and unwarranted interference with one’s self-presentation and public identity. The law of image gave rise to the phenomenon of the personal image lawsuit, in which individuals sued to vindicate or redress their image rights. By the postwar era, such lawsuits had become an established feature of the sociolegal landscape, occupying not only a prominent place on court dockets but also in the popular imagination. The growth in personal image litigation over the course of the 20th century was driven by Americans’ increasing sense of entitlement to their personal images. A confluence of social forces led individuals to cultivate a sense of possessiveness and protectiveness towards their images, which was legitimated and enhanced by the law.

This article offers a broad overview of the development of the modern “image torts” and the phenomenon of personal image litigation.

{ Samantha Barbas/SSRN | Continue reading }

ideas, law | December 13th, 2012 2:34 pm

Eternalism is a philosophical approach to the ontological nature of time, which takes the view that all points in time are equally “real”, as opposed to the presentist idea that only the present is real.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading | Thanks James }

time | December 12th, 2012 1:18 pm

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been the type of person who would rather eat five cookies or none at all. I’d rather give a desert away than share it, would rather devour than savor. My hormones fluctuate on a reliable monthly cycle, delivering a week of ravenous hunger against a week of complete ambivalence toward food. During the times when I’m eating-crazed, I love food and feel intensely happy because of my love of it. During the times when I’m eating-apathetic, I feel like food has no impact on my life, my interests, or my desires. These are not states I summon. They are states that occur and subside of their own accord. […]

The assumption in most food consumption advice directed toward women is that they are in the process of trying to lose weight or, at the very least, maintain it, hence the popular “guilt-free” title for so many recipes in women’s magazines. Any woman who pays attention to her food consumption is assumed to be interested first and foremost in body modification.

{ Charlotte Shane/TNI | Continue reading }

experience, food, drinks, restaurants, ideas | December 5th, 2012 3:02 pm

If everyone knows a tenth of the population dishonestly claims to observe alien spaceships, this can make it very hard for the honest alien-spaceship-observer to communicate fact that she has actually seen an alien spaceship.

{ OvercomingBias | Continue reading }

ideas | December 4th, 2012 5:57 am

ideas, photogs, technology | November 18th, 2012 4:11 pm

The three most disruptive transitions in history were the introduction of humans, farming, and industry. If another transition lies ahead, a good guess for its source is artificial intelligence in the form of whole brain emulations, or “ems,” sometime in roughly a century.

{ Overcoming Bias | Continue reading }

A case can be made that the hypothesis that we are living in a computer simulation should be given a significant probability. The basic idea behind this so-called “Simulation argument” is that vast amounts of computing power may become available in the future, and that it could be used, among other things, to run large numbers of fine-grained simulations of past human civilizations. Under some not-too-implausible assumptions, the result can be that almost all minds like ours are simulated minds, and that we should therefore assign a significant probability to being such computer-emulated minds rather than the (subjectively indistinguishable) minds of originally evolved creatures. And if we are, we suffer the risk that the simulation may be shut down at any time.

{ Nick Bostrom | Continue reading | Related: Nick Bostrom, Are you living in a computer simulation?, 2003 }

photo { Matthew Pillsbury }

future, ideas, photogs, technology | November 17th, 2012 3:44 am

Rousseau at fifty-three — afflicted by illness, temperamental and alone, an anguished, paranoiac conscience — sitting up at his desk in Wootton, in the 1760s: “Nothing about me must remain hidden or obscure. I must remain incessantly beneath the reader’s gaze, so that he may follow me in all the extravagances of my heart and into every last corner of my life.”

The Confessions are Rousseau’s response, in the form of a remedy, to the pain and contradictions of a human heart filled with content that can no longer be transmitted vertically, toward the heavens. The task of the accused to supply proof of innocence, to authenticate the rightness of his conduct, requires a new, lateral kind of divination. A community of readers, not saints, is what counts.

{ Ricky D’Ambrose/TNI | Continue reading }

photo { Brittany Markert }

ideas, photogs | November 16th, 2012 12:47 pm

This article looks in more depth at the different ways in which ideas about cashless societies were articulated and explored in pre-1900 utopian literature. Taking examples from the works of key writers such as Thomas More, Robert Owen, William Morris and Edward Bellamy, it discusses the different ways in which the problems associated with conventional notes-and-coins monetary systems were tackled as well as looking at the proposals for alternative payment systems to take their place. Ultimately, what it shows is that although the desire to dispense with cash and find a more efficient and less-exploitable payment system is certainly nothing new, the practical problems associated with actually implementing such a system remain hugely challenging.

{ MPRA/Academia | Continue reading }

economics, ideas | November 16th, 2012 3:55 am

I think we felt that happiness, the ideal of happiness, making happiness the goal of life is very vacuous. We thought rather that happiness is a subjective state of feeling. And if what you want to do is maximize this subjective state of feeling–being happy–then I think all you have to do is invent a psychic aspirin that makes you happy the whole time. I think drug dealers sort of promise something like that as well. But you wouldn’t want to say about someone made perpetually happy by being drugged or taking pills that that person is leading a good life. I think there’s a moral objection to that immediately comes. People will say: We were built for something else. We were made for something else; not to be idiotically happy the whole time. So, it’s the subjective element there that if you want to maximize happiness, you are really wanting to maximize just a state of feeling, divorced entirely from the pursuit of those things that would justifiably make you happy. I think that’s our main critique of happiness. Happiness is a byproduct of an achievement of doing something well, of realizing your potential, flourishing, and things of that kind.

{ Robert Skidelsky/EconTalk | Continue reading }

ideas | November 14th, 2012 10:11 am

James Joyce | November 6th, 2012 1:02 pm

In quantum mechanics, the uncertainty principle is any of a variety of mathematical inequalities asserting a fundamental limit to the precision with which certain pairs of physical properties of a particle, such as position x and momentum p, can be known simultaneously. The more precisely the position of some particle is determined, the less precisely its momentum can be known, and vice versa. The original heuristic argument that such a limit should exist was given by Werner Heisenberg in 1927, after whom it is sometimes named, as the Heisenberg principle. […]

Historically, the uncertainty principle has been confused with a somewhat similar effect in physics, called the observer effect, which notes that measurements of certain systems cannot be made without affecting the systems.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

photo { Jason Lazarus }

ideas, photogs, science | November 5th, 2012 2:50 pm

Assume that you can’t redistribute happiness or wealth within the marriage. If your spouse is unhappy you will be unhappy and if your spouse is happy you are likely to be happy; happy wife, happy life.

If you can’t redistribute happiness the play to make is to maximize total happiness. Maximizing total happiness means accepting apparent reductions in happiness when those result in even larger increases in happiness for your spouse. If you maximize the total, however, there will be more to go around and the reductions will usually be temporary.

{ Marginal Revolution | Continue reading }

photo { Sergiy Barchuk }

guide, ideas, relationships | November 4th, 2012 8:28 am

Every several years, IQ tests test have to be “re-normed” so that the average remains 100. This means that a person who scored 100 a century ago would score 70 today; a person who tested as average a century ago would today be declared mentally retarded. […]

Do rising IQ scores really mean we are getting smarter? […]

Implicit in Flynn’s argument that we are becoming “more modern” is that IQ gains are due to environmental factors, not genetic ones. […] He invokes environmental factors, for example, to explain the shrinking male/female IQ gap and debunk notions of innate differences in intelligence between men and women. He uses similar reasoning to explain IQ differences between developed and developing countries.

{ TNR | Continue reading }

photo { Johan Willner }

ideas, science, within the world | October 26th, 2012 9:18 am