Catching a frisbee is difficult. Doing so successfully requires the catcher to weigh a complex array of physical and atmospheric factors, among them wind speed and frisbee rotation. Were a physicist to write down frisbee-catching as an optimal control problem, they would need to understand and apply Newton’s Law of Gravity.

Yet despite this complexity, catching a frisbee is remarkably common. Casual empiricism reveals that it is not an activity only undertaken by those with a Doctorate in physics. It is a task that an average dog can master. Indeed some, such as border collies, are better at frisbee-catching than humans.

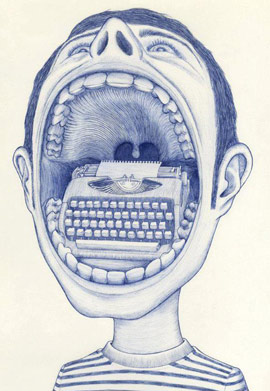

So what is the secret of the dog’s success? The answer, as in many other areas of complex decision-making, is simple. Or rather, it is to keep it simple. For studies have shown that the frisbee-catching dog follows the simplest of rules of thumb: run at a speed so that the angle of gaze to the frisbee remains roughly constant. Humans follow an identical rule of thumb.

Catching a crisis, like catching a frisbee, is difficult. Doing so requires the regulator to weigh a complex array of financial and psychological factors, among them innovation and risk appetite. Were an economist to write down crisis-catching as an optimal control problem, they would probably have to ask a physicist for help.

Yet despite this complexity, efforts to catch the crisis frisbee have continued to escalate. Casual empiricism reveals an ever-growing number of regulators, some with a Doctorate in physics. Ever-larger litters have not, however, obviously improved watchdogs’ frisbee-catching abilities. No regulator had the foresight to predict the financial crisis, although some have since exhibited supernatural powers of hindsight.

So what is the secret of the watchdogs’ failure? The answer is simple. Or rather, it is complexity. For what this paper explores is why the type of complex regulation developed over recent decades might not just be costly and cumbersome but sub-optimal for crisis control. In financial regulation, less may be more.

[…]

Modern finance is complex, perhaps too complex. Regulation of modern finance is complex, almost certainly too complex. That configuration spells trouble. As you do not fight fire with fire, you do not fight complexity with complexity. Because complexity generates uncertainty, not risk, it requires a regulatory response grounded in simplicity, not complexity.

Delivering that would require an about-turn from the regulatory community from the path followed for the better part of the past 50 years. If a once-in-a-lifetime crisis is not able to deliver that change, it is not clear what will. To ask today’s regulators to save us from tomorrow’s crisis using yesterday’s toolbox is to ask a border collie to catch a frisbee by first applying Newton’s Law of Gravity.

{ Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City | PDF }