ideas

The parent-offspring conflict theory delineates a zone of conflict between the mother and her offspring over weaning. We expect that the mother would try to wean her offspring off a little earlier than the offspring would be ready to wean themselves, thereby entering the zone of conflict for a short span of time. Though the theory was originally formulated in the context of weaning, it is also relevant in other contexts where a parent and his/her offspring have conflicting interests. Conflict has been reported over feeding, grooming, traveling, evening nesting, and mating in various species.

There are several theoretical models that address parent-offspring conflict in different contexts like reproduction, intra-brood competition, sexual conflict, and parental favoritism toward particular offspring. Though relatedness between parents, offspring and siblings can be measured easily, it is not easy to measure precisely parental investment and the costs and benefits to the concerned parties in nature. In some studies attempts have been made to quantify parental care in terms of milk ingested by offspring, sometimes as a correlate of weight gain by the individual pups, and sometimes by the duration of suckling. However, we have to accept that there is considerable variation in the suckling rates of individual pups, and in hunger levels of individuals, and hence such measures can only provide a rough estimate of parental investment. It is therefore not surprising that empirical tests of the theory in a field set up are sparse, especially in the original context of weaning. The parent-offspring conflict theory has in fact been claimed to be one of the most contentious subjects in behavioral and evolutionary ecology and also one of the most recalcitrant to experimental investigation.

{ arXiv | PDF }

animals, science, theory | May 13th, 2012 3:55 pm

A new study suggests that, by disrupting your body’s normal rhythms, your alarm clock could be making you overweight.

The study concerns a phenomenon called “social jetlag.” That’s the extent to which our natural sleep patterns are out of synch with our school or work schedules. Take the weekends: many of us wake up hours later than we do during the week, only to resume our early schedules come Monday morning. It’s enough to make your body feel like it’s spending the weekend in one time zone and the week in another. […]

Previous work with such data has already yielded some clues. “We have shown that if you live against your body clock, you’re more likely to smoke, to drink alcohol, and drink far more coffee,” says Roenneberg. […]

The researchers also found that people of all ages awoke and went to bed an average of 20 minutes later between 2002 and 2010. Work and school times have remained the same, meaning that social jetlag has increased during this period.

{ Science | Continue reading }

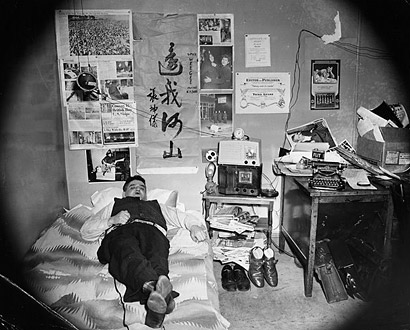

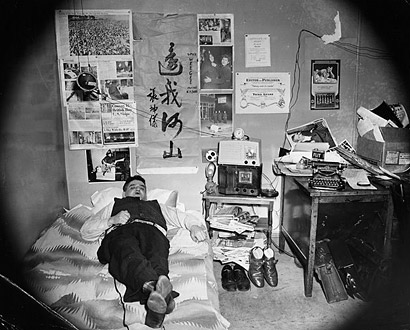

photo { Weegee in his apartment, police radio by his bedside }

health, science, sleep, time | May 11th, 2012 1:58 pm

The hypothesis was that people who used particular basic word orders would have more children. Testing this hypothesis directly, basic word order is a significant predictor of the number of children a person has (linear regression, controlling for age, sex, if the person was married, if they were employed their level of education and religion, t-value for basic word order = -18.179, p < 0.00001, model predicts 36% of the variance).

It turns out that speakers of SOV languages have more children than speakers of SVO languages, while speakers with no dominant order have the fewest children on average.

{ Replicated Typo | Continue reading }

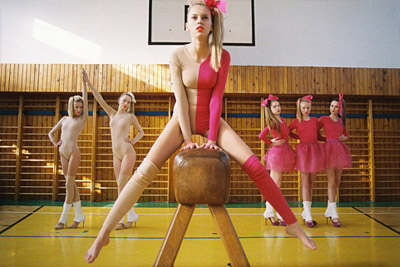

photo { Michal Pudelka }

Linguistics, kids | May 11th, 2012 1:47 pm

Small children (age 4-6) who were exposed to a large number of children’s books and films had a significantly stronger ability to read the mental and emotional states of other people. … The more absorbed subjects were in the story, the more empathy they felt, and the more empathy they felt, the more likely the subjects were to help when the experimenter “accidentally” dropped a handful of pens… Reading narrative fiction … fosters empathic growth and prosocial behavior. […]

Psychologists have found that people who watch less TV are actually more accurate judges of life’s risks and rewards than those who subject themselves to the tales of crime, tragedy, and death that appear night after night on the ten o’clock news. That’s because these people are less likely to see sensationalized or one-sided sources of information, and thus see reality more clearly.

{ OvercomingBias | Continue reading }

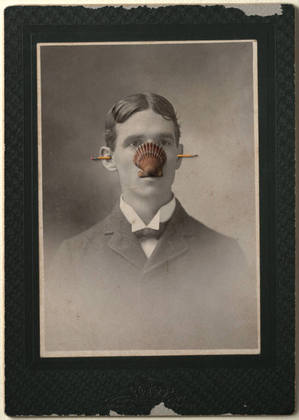

image { Gary Stephen Brotmeyer }

books, ideas, media, psychology | May 11th, 2012 12:06 pm

I’m what they call a media ecologist, so I believe in media environments — both explicit ones and implicit ones. So it’s like the lightbulb is a media environment, right? You turn on the lightbulb, and you have a different environment because of that medium. But print is a media environment that encourages certain ways of looking at the world. Television changes us. Internet is a media environment. Somehow our media environment, combined with our economic environment, can really amplify one another’s effects in dangerous ways.

Way back in the mid-1990s — when Wired announced that we’re living in an attention economy, when everyone came up with these metrics to measure eyeball hours and the “stickiness” of websites — there was this competition to get our attention. Parallel to that is the sudden emergence of all these attention disorders and new prescriptions for Ritalin. So I’m thinking, we’re living in an attention economy, in which it’s been declared by Wall Street that the one commodity we’ve got to extend in order to make more money is human attention. And then we start drugging our children to pay more attention. I can’t help but worry. Not that there’s a specific conspiracy — Oh, let’s drug the children so they pay more attention — but rather, we’re living in a world where the brunt of our technological know-how is being spent on maintaining attention. Kids start to show these defense mechanisms against paying attention.

{ Douglas Rushkoff interviewed by Samantha Hinds | Continue reading }

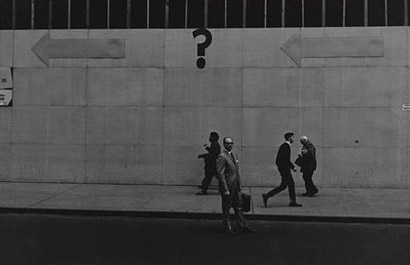

photo { Christian Patterson }

ideas | May 9th, 2012 3:51 pm

Modernity became obsessed with analysis and the elimination of vague, ambiguous, or contradictory ideas. We fell almost completely under its sway and came to imagine that the picture of reality that such thinking provided gave us the best way to understand our world and our place in it.

It was as if we had finally found our way out of the cave and into the kind of light that Plato had thought existed with the Platonic forms. It appeared that modern thinkers had found their way out of the shadowy and mysterious realm of our actual experience and found the kind of certainty that Plato had sought.

Today, however, we are able to see that from a very different perspective because of what we know concerning the human brain. We now know that as appealing as such certainty is, it merely represents one way that the human brain is capable of thinking. Instead of the moving picture of our actual experience, we are capable of ideas that represent snap shots, which make the distances, perspectives, and relations that we actually experience appear fixed and give us the kind of clear and distinct ideas that we crave.

In the seventh book of the Republic, Plato sets forth his famous allegory of the cave. The traditional understanding interpreted it as Plato arguing that both becoming and being were real because there were two different worlds or realms of reality. One was the world of sense-data, which the Pre-Socratic philosopher, Heraclitus argued was purely a matter of becoming. In this world, nothing ever exists in a pure state of being but is always becoming something else.

Plato however, claimed that there was another world where things did exist in a pure state of being. Parmenides and several other Pre-Socratic philosophers had long claimed that the world of which Heraclitus spoke was an illusory world produced by a naïve trust in our unreliable senses and that in fact reason showed us that only being truly existed and all becoming and change was illusory. Plato agreed with both Heraclitus and Parmenides: he believed that the world of our sense data was real and not merely illusory, but there was also a world of pure being - the parallel universe that Plato would come to describe as the world of the forms.

{ The Philosopher | Continue reading }

photo { Steve Schapiro, Samuel Beckett Looking at Parrot, New York, 1964 }

brain, ideas | May 9th, 2012 7:32 am

Team-building exercises, simulation games, educational games, puzzle-solving activities, office parties, themed dress-down days, and colorful, aesthetically-stimulating workplaces are notable examples of this trend. […]

This is a relatively new conception of the relation between work and play. Until very recently, play was seen as the antithesis of work (see Kavanagh, this issue). Classical industrial theory, for example, hinges on a fundamental distinction between waged labour and recreation. Play at work is thought to pose a threat not only to labour discipline, but also to the very basis of the wage bargain: In exchange for a day’s pay, workers are expected to leave their pleasures at home. […]

When employees are urged to reach out to their ‘inner child,’ it becomes clear that the distinction between work and play is increasingly difficult to maintain in practice.

With such blurring of work and play, the traditional boundary between economic and artistic production also disappears. In much of the business literature on play, the entrepreneur and the artist melt into one figure. […]

Yet while contemporary organizations have colonized play for profit-seeking purposes, this inevitably has unforeseen consequences. Play may turn back against the organization and disrupt its smooth functioning; the managers who open a game in the organization may find that they lose control over it and come to realize that play is occasionally able to usurp work rather than stimulate it. Play serves organizational objectives only insofar as it is kept within certain ludic limits. […]

This special issue emerged from an ephemera conference on ‘Work, Play and Boredom’ held at the University of St Andrews in May 2010. At the heart of the conference was the idea that ‘boredom’ might be an appropriate concept for rethinking the interconnections between work and play in present-day organizations.

{ ephemera | PDF }

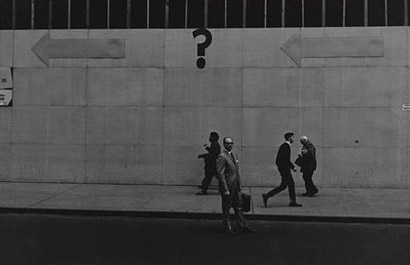

photo { Lee Friedlander, New York City, 1962 }

economics, ideas, leisure | May 8th, 2012 10:54 am

If we look at how communication works we find that words and phrases have a great influence on attention. They bring into the consciousness of the listener the concepts that are uttered. This is what meaning is – the concepts that a word or phrase can steer attention towards. This is what communication is – the sharing of attention by two (or more) brains on a sequence of concepts.

So it is not surprising that it is useful to talk to oneself. What we are doing when we self-talk is to steer our consciousness. In recent paper, Lupyan and Swingley look at how self-directed speech affects searching.

{ Thoughts on thoughts | Continue reading }

Linguistics, psychology | May 8th, 2012 10:54 am

When you “lose yourself” inside the world of a fictional character while reading a story, you may actually end up changing your own behavior and thoughts to match that of the character, a new study suggests.

Researchers at Ohio State University examined what happened to people who, while reading a fictional story, found themselves feeling the emotions, thoughts, beliefs and internal responses of one of the characters as if they were their own - a phenomenon the researchers call “experience-taking.”

They found that, in the right situations, experience-taking may lead to real changes, if only temporary, in the lives of readers.

{ Ohio State University | Continue reading }

photo { Joel Sternfeld }

books, psychology | May 7th, 2012 1:44 pm

Are straight people born that way? (…) We have to start with a more fundamental question: What do we mean when we say someone is “straight”? At the most basic level, we seem to be imagining female bodies that are specifically sexually aroused by male bodies, and vice versa.

Laboratory studies (…) suggest that, while such people probably do exist — at least in North America, where many sexologists have focused their attentions – it’s not uncommon for straight-identified people to be at least a little aroused by the idea of same-sex relations.

The media has tended to broadcast the news that gay-identified men and straight-identified men have quite discernible arousal patterns when they are shown various kinds of sexual stimuli. And that’s true. But if you look closely at the data, you’ll see that most straight-identified men do tend to show a little bit of arousal across sex categories (as do gay-identified men).

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

painting { Ingres, Madame Moitessier, 1856 }

ideas, relationships, science, sex-oriented | May 3rd, 2012 12:41 pm

It is possible to have Hunger-Games-like situations where everyone strongly expects everyone to fight until only one is left standing. And yes, in such situations you are better off hitting first, before they can hit you. But the first question you should always ask is, just how sure are you that you are in fact in such a situation.

This is what I think every time I hear people talk about inevitable future conflicts, be they Earth v. alien, robots v. humans, human v. animal, west v. east, rich v. poor, liberal v. conservative, religious vs. athiest, smart v. dumb, etc. Yes, if enough folks will see this as unrestrained war to the death, then you should consider striking first. And yes, there probably will be some sort of war eventually. But if you are wrong about the war being likely soon, you could cause vast needless destruction.

{ Overcomingbias | Continue reading }

photo { Facundo Pires }

ideas | May 3rd, 2012 12:41 pm

The first perspective produces legislative atrocities like the proposed New York City bill that would have penalized taxi drivers for transporting prostitutes. (…)

I’m in favor of legalizing all forms of sex work for adults—not because I think it’s necessarily such great work, but because I think being a legal worker is better than being an illegal worker.

{ Jacobin | Continue reading }

economics, ideas, sex-oriented | May 3rd, 2012 7:54 am

For decades, a small group of scientific dissenters has been trying to shoot holes in the prevailing science of climate change, offering one reason after another why the outlook simply must be wrong.

Over time, nearly every one of their arguments has been knocked down by accumulating evidence, and polls say 97 percent of working climate scientists now see global warming as a serious risk.

Yet in recent years, the climate change skeptics have seized on one last argument that cannot be so readily dismissed. Their theory is that clouds will save us.

They acknowledge that the human release of greenhouse gases will cause the planet to warm. But they assert that clouds — which can either warm or cool the earth, depending on the type and location — will shift in such a way as to counter much of the expected temperature rise and preserve the equable climate on which civilization depends.

Their theory exploits the greatest remaining mystery in climate science, the difficulty that researchers have had in predicting how clouds will change. The scientific majority believes that clouds will most likely have a neutral effect or will even amplify the warming, perhaps strongly, but the lack of unambiguous proof has left room for dissent.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

photo { Robert Whitman }

climate, theory | May 1st, 2012 8:59 am

In 1927, Gestalt psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik noticed a funny thing: waiters in a Vienna restaurant could only remember orders that were in progress. As soon as the order was sent out and complete, they seemed to wipe it from memory.

Zeigarnik then did what any good psychologist would: she went back to the lab and designed a study. A group of adults and children was given anywhere between 18 and 22 tasks to perform (both physical ones, like making clay figures, and mental ones, like solving puzzles)—only, half of those tasks were interrupted so that they couldn’t be completed. At the end, the subjects remembered the interrupted tasks far better than the completed ones—over two times better, in fact. (…)

Your mind (…) wants to finish. It wants to keep working – and it will keep working even if you tell it to stop. All through those other tasks, it will subconsciously be remembering the ones it never got to complete. Psychologist Arie Kruglanski calls this a Need for Closure, a desire of our minds to end states of uncertainty and resolve unfinished business. This need motivates us to work harder, to work better, and to work to completion.

The Zeigarnik Effect that has been demonstrated many times, in many contexts – but each time I see it or read about it, I can’t help but think of (…) Socrates’ reproach in The Phaedrus that the written word is the enemy of memory. (…)

Ernest Hemingway telling George Plimpton in his 1958 Paris Review interview that, “though there is one part of writing that is solid and you do it no harm by talking about it, the other is fragile, and if you talk about it, the structure cracks and you have nothing.”

{ Maria Konnikova/Scientific American | Continue reading }

photo { Picasso, Le peintre et son modèle, 1914 }

ideas, psychology | May 1st, 2012 8:59 am

David Eagleman, neuroscientist: Take the vast, unconscious, automated processes that run under the hood of conscious awareness. We have discovered that the large majority of the brain’s activity takes place at this low level. The conscious part – the “me” that flickers to life when you wake up in the morning – is only a tiny bit of the operations. This understanding has given us a better understanding of the complex multiplicity that makes a person. A person is not a single entity of a single mind: a human is built of several parts, all of which compete to steer the ship of state. As a consequence, people are nuanced, complicated, contradictory. We act in ways that are sometimes difficult to detect by simple introspection. (…)

Raymond Tallis, former professor of geriatric medicine: [You] present us as more helpless, ignorant and zombie-like than is compatible with the kinds of lives we actually live and, what’s more, with doing brain science.

{ Guardian | Continue reading }

related { How free is the will? }

photo { Heiner Luepke }

ideas, neurosciences | April 30th, 2012 11:04 am

The scientists individually told each member of another group of randomly selected people, “I hate to tell you this, but no one chose you as someone they wanted to work with.” (…) the whole point of going through all of this as far as the students knew, was to sit in front of a bowl containing 35 mini chocolate-chip cookies and judge those cookies on taste, smell, and texture. The subjects learned they could eat as many as they wanted while filling out a form commonly used in corporate taste tests. The researchers left them alone with the cookies for 10 minutes.

This was the actual experiment – measuring cookie consumption based on social acceptance. How many cookies would the wanted people eat, and how would their behavior differ from the unwanted? (…) Why did the rejected group feel motivated to keep mushing cookies into their sad faces? (…)

The answer has to do with something psychologists now call ego depletion, and you would be surprised to learn how many things can cause it, how often you feel it, and how much in life depends on it.

{ You Are Not So Smart | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology | April 30th, 2012 5:57 am

The worst part of philosophy is the philosophy of science; the only people, as far as I can tell, that read work by philosophers of science are other philosophers of science. It has no impact on physics whatsoever, and I doubt that other philosophers read it because it’s fairly technical. And so it’s really hard to understand what justifies it. And so I’d say that this tension occurs because people in philosophy feel threatened, and they have every right to feel threatened, because science progresses and philosophy doesn’t. (…) Well, yeah, I mean, look I was being provocative.

{ Lawrence Krauss | Continue reading }

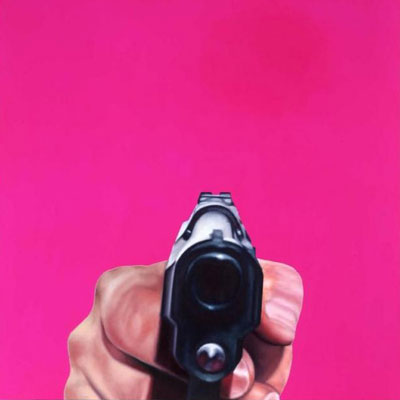

artwork { James Rosenquist, Pink Condition, 1996 }

ideas | April 26th, 2012 10:50 am

Forget your personal tragedy.

We are all bitched from the start and you especially have to hurt like hell before you can write seriously. But when you get the damned hurt use it—don’t cheat with it. Be as faithful to it as a scientist—but don’t think anything is of any importance because it happens to you or anyone belonging to you.

{ Ernest Hemingway to Scott Fitzgerald | Continue reading }

experience, ideas | April 26th, 2012 10:25 am

Food intended to be eaten hot, and supplied hot, is subject to 20 per cent VAT. Food intended to be eaten hot, but not supplied hot – fish and chips bought in a supermarket – is zero rated. But what of food supplied hot and intended to be eaten cold such as freshly baked bread? (…)

Fine, but arbitrary, distinctions, are endemic in tax systems. But problems such as these are not confined to tax policy. When we regulate bank capital, we observe that a loan to another financial institution differs from a mortgage. But what of a loan to another financial institution whose repayment depends on the performance of a mortgage?

{ John Kay | Continue reading }

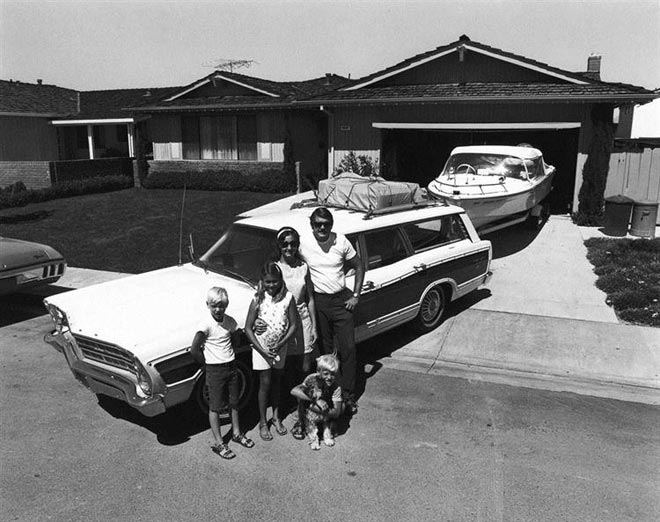

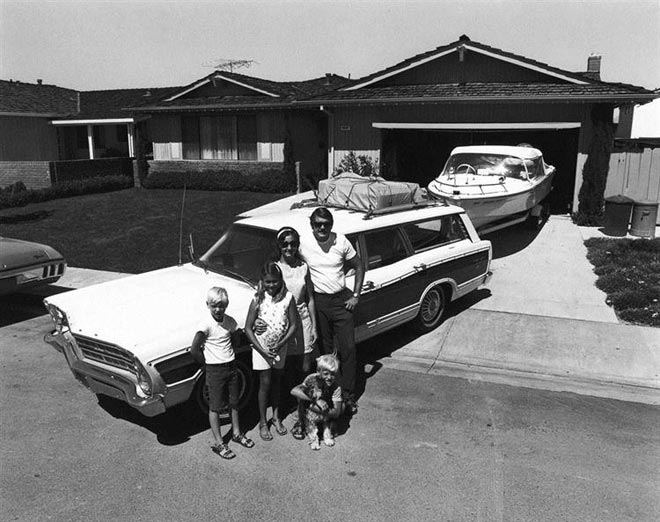

photo { Bill Owens }

economics, ideas | April 26th, 2012 7:40 am

I call it the Argument from Hypocrisy. It goes something like this:

1. Lots of people say that X is wrong.

2. But these people almost always do X.

3. Therefore, even the opponents of X don’t really believe X is wrong.

4. So X probably isn’t really wrong.

{ Bryan Caplan/EconLib | Continue reading }

ideas | April 25th, 2012 3:40 pm