ideas

Since quite a long time neuroscientists know where the process of creative thinking takes place in the brain: mainly in the frontal lobe. The part of the brain behind our forehead is responsible for the production of ideas that are not only original, rare and uncommon but also appropriate, thus useful and adaptive. Against that background, findings about impairments in creative cognition as a consequence of frontal lobe damages are not surprising.

The neuroscientists Shamay-Tsoory et al. however, looked at this relation a little bit closer. Lesions in the frontal lobe do not always entail negative consequences for creativity. Rather on the contrary.

{ United Academics | Continue reading }

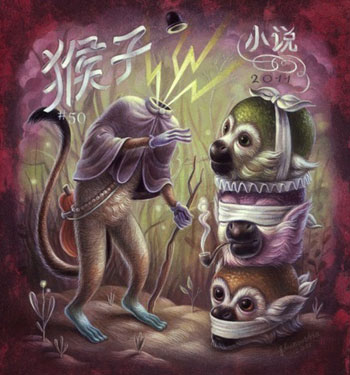

artwork { Femke Hiemstra }

brain, ideas | March 26th, 2012 1:12 pm

Today’s word: the business term for membership services (gyms, streaming music) being paid for but not used is “breakage.”

{ Sasha Frere-Jones }

photo { Nathaniel Ward }

Linguistics, photogs | March 26th, 2012 7:44 am

Researchers have established a direct link between the number of friends you have on Facebook and the degree to which you are a “socially disruptive” narcissist, confirming the conclusions of many social media skeptics.

People who score highly on the Narcissistic Personality Inventory questionnaire had more friends on Facebook, tagged themselves more often and updated their newsfeeds more regularly.

The research comes amid increasing evidence that young people are becoming increasingly narcissistic, and obsessed with self-image and shallow friendships.

A number of previous studies have linked narcissism with Facebook use, but this is some of the first evidence of a direct relationship between Facebook friends and the most “toxic” elements of narcissistic personality disorder.

{ Guardian | Continue reading }

photo { Leo Berne }

quote { Hamilton Nolan/Gawker }

gross, ideas, psychology, social networks, technology | March 25th, 2012 11:18 am

Defamiliarization or ostranenie is the artistic technique of forcing the audience to see common things in an unfamiliar or strange way, in order to enhance perception of the familiar.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

photo { Philip-Lorca diCorcia }

Linguistics, ideas, photogs | March 23rd, 2012 12:13 pm

The problem with the web is that it largely began as a world separate from meatspace. Today, most people use their real names, but this wasn’t always the case. When I started going online in the mid-90s, no one even knew my gender. I preferred that, not because I was hiding, but because I feel very strongly that I should be judged by my thoughts, not who people assume I am by seeing I am a woman, by attaching a handful of preconceived notions to what I am saying because they see my photo and think I’m too young or too old or attractive or unattractive. (…)

There is nothing wrong with wishing that it were possible to compartmentalize your digital conversations in the same way you do your meatspace exchanges. Unfortunately for us, this is not the direction the web is going, which is why pseudonymous accounts and the networks who accept them are so very, very important.

{ AV Flox | Continue reading }

image { Mark Gmehling }

experience, ideas, technology | March 23rd, 2012 11:48 am

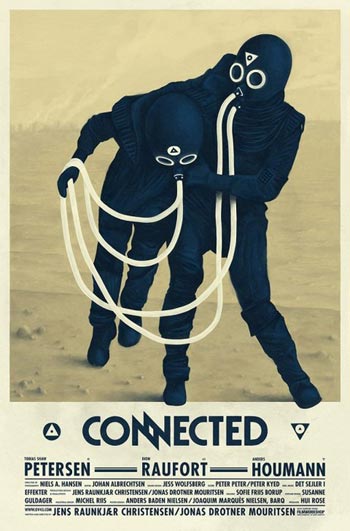

A Christian missionary sets out to convert a remote Amazonian tribe. He lives with them for years in primitive conditions, learns their extremely difficult language, risks his life battling malaria, giant anacondas, and sometimes the tribe itself. In a plot twist, instead of converting them he loses his faith, morphing from an evangelist trying to translate the Bible into an academic determined to understand the people he’s come to respect and love.

Along the way, the former missionary discovers that the language these people speak doesn’t follow one of the fundamental tenets of linguistics, a finding that would seem to turn the field on its head, undermine basic assumptions about how children learn to communicate, and dethrone the discipline’s long-reigning king, who also happens to be among the most well-known and influential intellectuals of the 20th century.

{ The Chronicle of Higher Education | Continue reading }

image { The Connected Poster }

Linguistics | March 23rd, 2012 11:35 am

Philosophically, a realist is someone who holds that our theories are descriptions of how the world really is. Yet realist explanations of the behaviour of elementary particles face a fundamental challenge. Although electrons, for example, would seem to be simple entities – they have no internal structure – a satisfactory description of their behaviour in classical Newtonian terms, as if they were little balls, proved impossible. Theorists therefore turned to building mathematical models which could predict electron behaviour rather than explain electrons in realist terms.

Instrumentalism is this view that theories are useful for explaining and predicting phenomena, rather than that they necessarly describe the world. Yet the mathematical apparatus underpinning such instrumentalism, such as Dirac’s use of infinite-dimensional Hilbert [abstract mathematical] spaces, and Feynman’s sums-over-all-possible-histories, are so powerful, and so beautiful, that the lack of a convincing realist alternative has so far not proved to be a significant handicap in the development of quantum physics and its technological applications. In fact, quantum theory in its instrumental form has provided the most successful explanation of all time, by being the most powerful of all scientific theories. But Deutsch wants a realist quantum theory.

{ Philosophy Now | Continue reading }

artwork { Olaf Brzeski, Dream, Spontaneous Combustion, 2008 }

ideas, theory | March 23rd, 2012 11:15 am

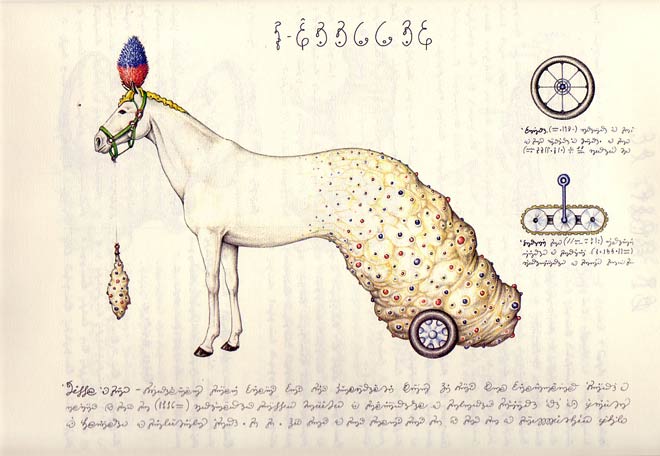

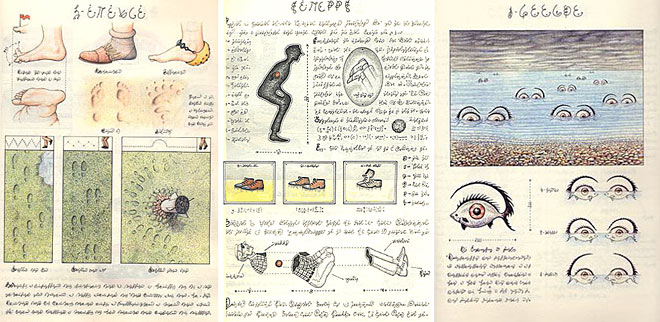

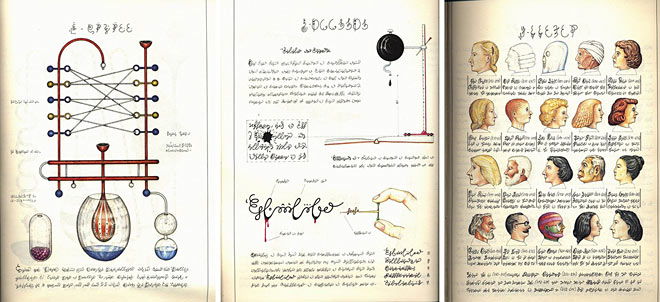

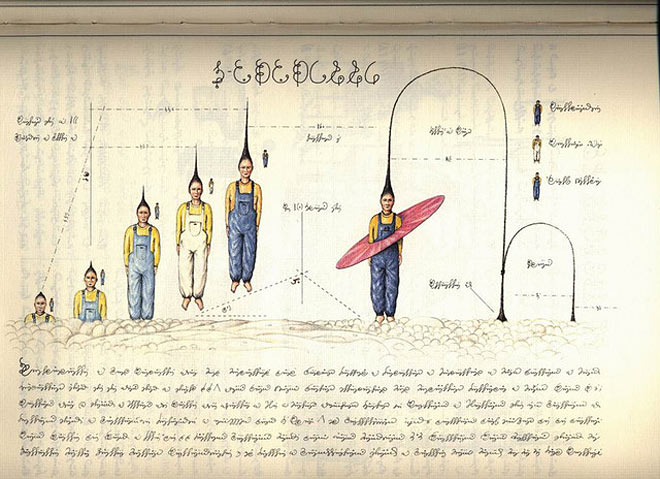

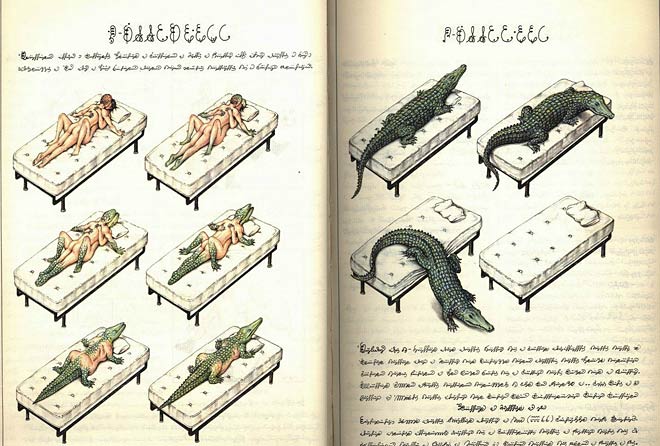

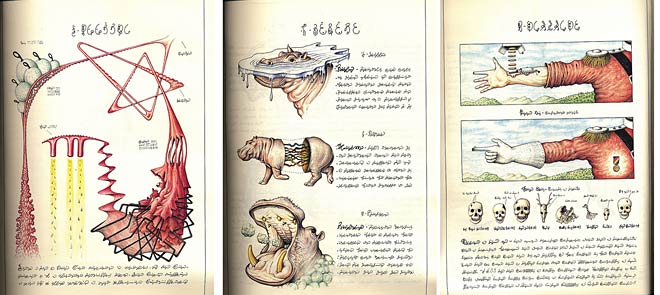

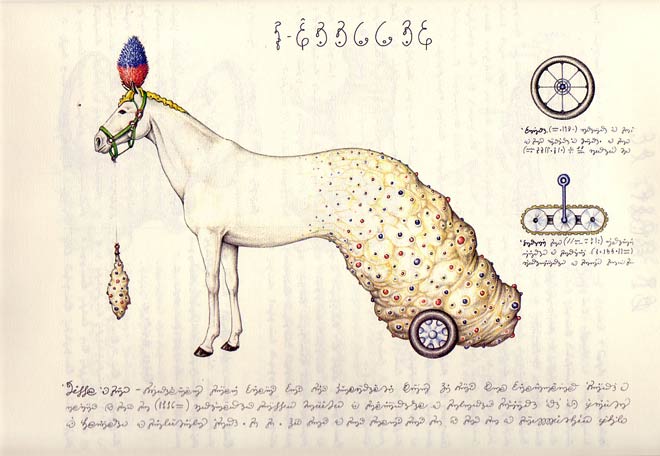

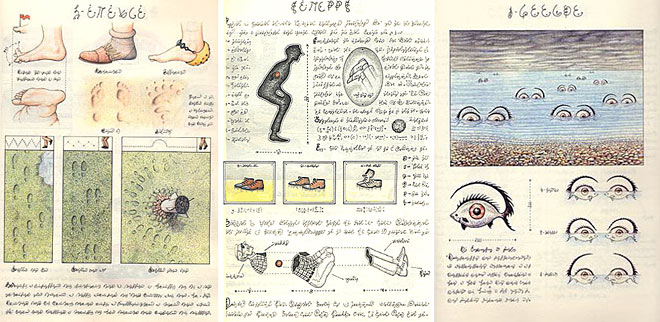

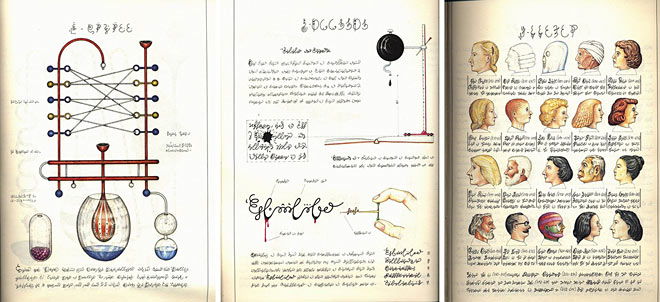

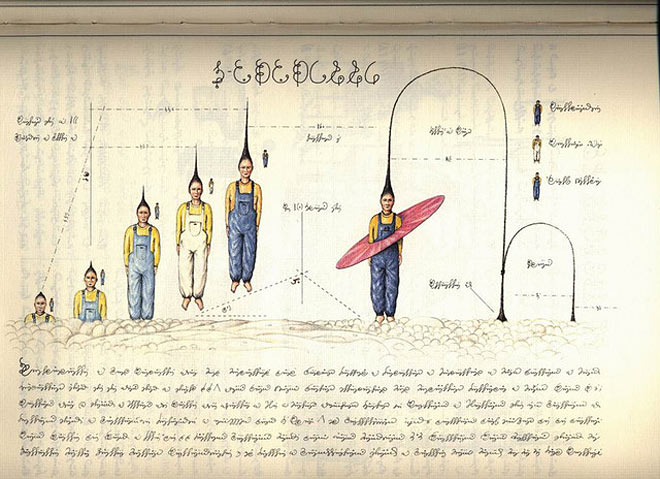

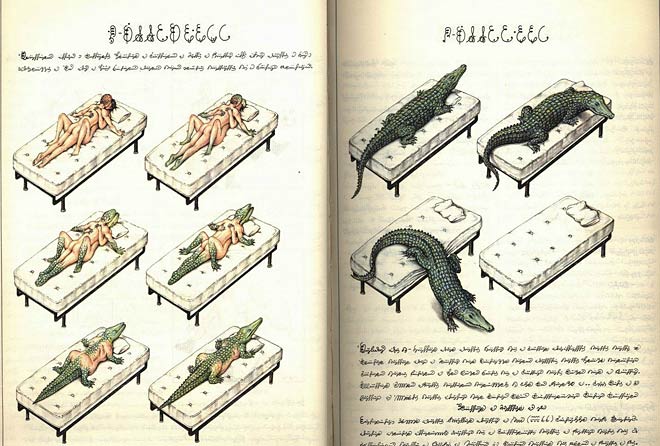

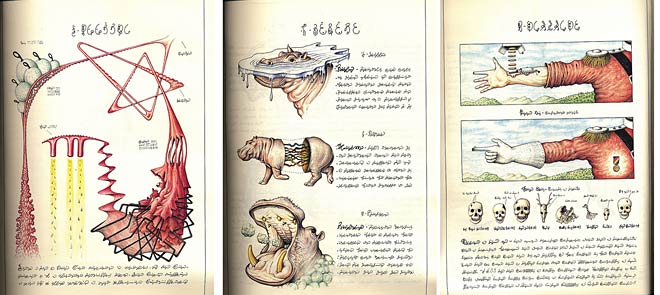

Codex Seraphinianus, originally published in 1981, is an illustrated encyclopedia of an imaginary world, created by the Italian artist, architect and industrial designer Luigi Serafini during thirty months, from 1976 to 1978. The book is approximately 360 pages long (depending on edition), and written in a strange, generally unintelligible alphabet. (…)

The book is an encyclopedia in manuscript with copious hand-drawn colored-pencil illustrations of bizarre and fantastical flora, fauna, anatomies, fashions, and foods. It has been compared to the Voynich manuscript,[3] “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius”, and the works of M.C. Escher[6] and Hieronymus Bosch. (…)

In a talk at the Oxford University Society of Bibliophiles held on 12 May 2009, Serafini stated that there is no meaning hidden behind the script of the Codex, which is asemic; that his own experience in writing it was closely similar to automatic writing; and that what he wanted his alphabet to convey to the reader is the sensation that children feel in front of books they cannot yet understand, although they see that their writing does make sense for grown-ups.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading | Thanks to Adam John Williams }

books, visual design | March 23rd, 2012 10:05 am

Love is an alien invasion coordinated with sleeper cell revolts. Someone penetrates you and leaves behind a colony that allows the monster inside them to ventriloquize your thoughts. It’s the opportunity that that part of us which cries out to be dominated and longs to be victimized has been waiting for ever since we were born. Everyone knows the best scene in The Manchurian Candidate is the one where Frank Sinatra and Janet Leigh meet on the train. It captures the indistinguishabilty of love from brainwashing, even and especially at its inception. Love is a cancer. You can’t just cut it out. You have to poison your whole body to beat it, kill yourself just enough to keep on living. Love is White Power. Love is Vichy France.

–-Rick Santorum, National Association of Women Against Women, inaugural address

{ If you can read this you’re lying | Continue reading }

painting { Jules Lefebvre, Odalisque, 1874 }

ideas, relationships | March 21st, 2012 2:58 pm

A team of physicists published a paper drawing on Google’s massive collection of scanned books. They claim to have identified universal laws governing the birth, life course and death of words.

Published in Science, that paper gave the best-yet estimate of the true number of words in English—a million, far more than any dictionary has recorded (the 2002 Webster’s Third New International Dictionary has 348,000). More than half of the language, the authors wrote, is “dark matter” that has evaded standard dictionaries.

The paper also tracked word usage through time (each year, for instance, 1% of the world’s English-speaking population switches from “sneaked” to “snuck”). It also showed that we seem to be putting history behind us more quickly, judging by the speed with which terms fall out of use. References to the year “1880″ dropped by half in the 32 years after that date, while the half-life of “1973″ was a mere decade. (…)

English continues to grow—the 2011 Culturonomics paper suggested a rate of 8,500 new words a year. The new paper, however, says that the growth rate is slowing. Partly because the language is already so rich, the “marginal utility” of new words is declining: Existing things are already well described. This led them to a related finding: The words that manage to be born now become more popular than new words used to get, possibly because they describe something genuinely new (think “iPod,” “Internet,” “Twitter”).

{ WSJ | Continue reading }

image { Larry Welz }

Linguistics | March 20th, 2012 12:32 pm

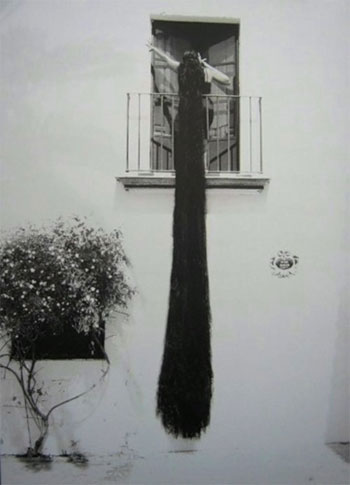

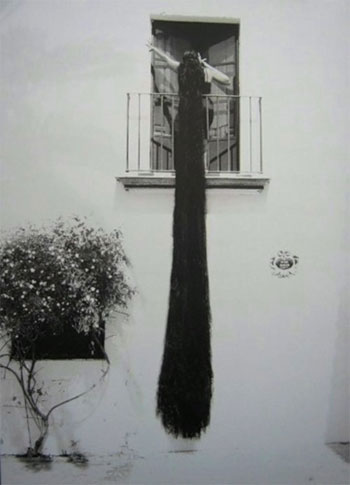

Throughout the centuries hair has been a symbol of status for wealth, class, rank, slavery, royalty, strength, manliness or femininity. And, it still holds a place of value in our postmodern era. Two novels that include hair as a major theme are Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (1991) and Don Delillo’s Cosmopolis (2003). These two authors create characters heavily involved in the Wall Street world but also swallowed up in their depthless narcissism.

In American Psycho we are introduced to twenty-eight year old Patrick Bateman, a psychopath serial killer who is also a wealthy, narcissistic Wall Street broker. Bateman’s first person narrative is filled with the gruesome crimes he commits, but they are narrated in such a way that it is never clear if he is actually performing the murders. He is obsessed with the material world and confines his life to eating at fancy restaurants, womanizing, purchasing name brand clothes and the most up-to-date electronics, and ensuring the preciseness of his hair.

Twenty-eight year old Eric Packer of Cosmopolis follows many of the traits of his predecessor, but, instead of aimless wandering from fashionable restaurants to name brand designer shops, Packer sets out across New York on a mini-epic journey for a haircut. In his maximum security limousine, Packer views the world from multiple digital screens and purposefully loses his entire financial portfolio in a gamble against the Japanese yen. Within these two novels, hair functions as the external symbol of inward turmoil. Hair becomes a primary symbol through which these two authors create a harsh critique of the modern world of technology, consumerism, and emptiness.

{ Wayne E. Arnold | Continue reading }

books, hair | March 20th, 2012 12:20 pm

Most of us would agree that King Tut and the other mummified ancient Egyptians are dead, and that you and I are alive. Somewhere in between these two states lies the moment of death. But where is that? The old standby — and not such a bad standard — is the stopping of the heart. But the stopping of a heart is anything but irreversible. We’ve seen hearts start up again on their own inside the body, outside the body, even in someone else’s body. Christian Barnard was the first to show us that a heart could stop in one body and be fired up in another. Due to the mountain of evidence to the contrary, it is comical to consider that “brain death” marks the moment of legal death in all fifty states. (…)

Sorensen says that the idea of “irreversibility” makes the determination of death problematic. What was irreversible, say, twenty years ago, may be routinely reversible today. He cites the example of strokes. Brain damage from stroke that was irreversible and led irrevocably to death in the 1940s was reversible in the 1980s. In 1996 the FDA approved tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), a clot-dissolving agent, for use against stroke. This drug has increased the reversibility of a stroke from an hour after symptoms begin to three hours.

In other words, prior to 1996, MRIs of the brains of stroke victims an hour after the onset of symptoms were putative photographs of the moment of death, or at least brain death. Today those images are meaningless.

{ Salon | Continue reading }

health, ideas | March 20th, 2012 12:09 pm

You’re famous for denying that propositions have to be either true or false (and not both or neither) but before we get to that, can you start by saying how you became a philosopher?

Well, I was trained as a mathematician. I wrote my doctorate on (classical) mathematical logic. So my introduction into philosophy was via logic and the philosophy of mathematics. But I suppose that I’ve always had an interest in philosophical matters. I was brought up as a Christian (not that I am one now). And even before I went to university I was interested in the philosophy of religion – though I had no idea that that was what it was called. Anyway, by the time I had finished my doctorate, I knew that philosophy was more fun than mathematics, and I was very fortunate to get a job in a philosophy department (at the University of St Andrews), teaching – of all things – the philosophy of science. In those days, I knew virtually nothing about philosophy and its history. So I have spent most of my academic life educating myself – usually by teaching things I knew nothing about; it’s a good way to learn! Knowing very little about the subject has, I think, been an advantage, though. I have been able to explore without many preconceptions. And I have felt free to engage with anything in philosophy that struck me as interesting.

{ Graham Priest interviewed by Richard Marshal | Continue reading }

photo { Robert Whitman }

ideas | March 19th, 2012 3:04 pm

Several theories claim that dreaming is a random by-product of REM sleep physiology and that it does not serve any natural function.

Phenomenal dream content, however, is not as disorganized as such views imply. The form and content of dreams is not random but organized and selective: during dreaming, the brain constructs a complex model of the world in which certain types of elements, when compared to waking life, are underrepresented whereas others are over represented. Furthermore, dream content is consistently and powerfully modulated by certain types of waking experiences.

On the basis of this evidence, I put forward the hypothesis that the biological function of dreaming is to simulate threatening events, and to rehearse threat perception and threat avoidance.

To evaluate this hypothesis, we need to consider the original evolutionary context of dreaming and the possible traces it has left in the dream content of the present human population. In the ancestral environment, human life was short and full of threats. Any behavioral advantage in dealing with highly dangerous events would have increased the probability of reproductive success. A dream-production mechanism that tends to select threatening waking events and simulate them over and over again in various combinations would have been valuable for the development and maintenance of threat-avoidance skills.

Empirical evidence from normative dream content, children’s dreams, recurrent dreams, nightmares, post traumatic dreams, and the dreams of hunter-gatherers indicates that our dream-production mechanisms are in fact specialized in the simulation of threatening events, and thus provides support to the threat simulation hypothesis of the

{ Antti Revonsuo/Behavioral and Bain Sciences | PDF }

archives, psychology, science, theory | March 19th, 2012 3:02 pm

We have all had arguments. Occasionally these reach an agreed upon conclusion but usually the parties involved either agree to disagree or end up thinking the other party hopelessly stupid, ignorant or irrationally stubborn. Very rarely do people consider the possibility that it is they who are ignorant, stupid, irrational or stubborn even when they have good reason to believe that the other party is at least as intelligent or educated as themselves.

Sometimes the argument was about something factual where the facts could be easily checked e.g. who won a certain football match in 1966.

Sometimes the facts aren’t so easily checked because they are difficult to understand but the problem is clear and objective. (…)

Sometimes the facts aren’t as mathematical or logical as the Monty Hall solution. Each party to the argument appeals to ‘facts’ which the other party disputes. (…)

Sometimes the arguments boil down to differences in values. For example, what tastes better chocolate or vanilla ice cream, or who is prettier Jane or Mary? In these cases there isn’t really a correct answer – even when a large majority favors a particular alternative. Values also have a strong way of influencing what people accept as evidence or indeed what they perceive at all.

The interesting thing is that when the disagreement isn’t a pure values difference it should always be possible to reach agreement.

{ Garth Zietsman | Continue reading }

controversy, ideas, relationships | March 19th, 2012 12:13 pm

New support for the value of fiction is arriving from an unexpected quarter: neuroscience.

Brain scans are revealing what happens in our heads when we read a detailed description, an evocative metaphor or an emotional exchange between characters. Stories, this research is showing, stimulate the brain and even change how we act in life.

Researchers have long known that the “classical” language regions, like Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area, are involved in how the brain interprets written words. What scientists have come to realize in the last few years is that narratives activate many other parts of our brains as well, suggesting why the experience of reading can feel so alive. Words like “lavender,” “cinnamon” and “soap,” for example, elicit a response not only from the language-processing areas of our brains, but also those devoted to dealing with smells. (…)

Researchers have discovered that words describing motion also stimulate regions of the brain distinct from language-processing areas. (…)

The brain, it seems, does not make much of a distinction between reading about an experience and encountering it in real life; in each case, the same neurological regions are stimulated. (…) Fiction — with its redolent details, imaginative metaphors and attentive descriptions of people and their actions — offers an especially rich replica. Indeed, in one respect novels go beyond simulating reality to give readers an experience unavailable off the page: the opportunity to enter fully into other people’s thoughts and feelings. (…) Scientists call this capacity of the brain to construct a map of other people’s intentions “theory of mind.” Narratives offer a unique opportunity to engage this capacity, as we identify with characters’ longings and frustrations, guess at their hidden motives and track their encounters with friends and enemies, neighbors and lovers. (…)

Reading great literature, it has long been averred, enlarges and improves us as human beings. Brain science shows this claim is truer than we imagined.

{ NYT | Continue reading }

books, neurosciences, psychology | March 19th, 2012 12:10 pm

Wallace had been taking Nardil for his depression since 1989. Nardil is a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, or MAOI, a member of the earliest generation of antidepressants; newer drugs are usually not only more effective against the illness but also less likely to cause collateral damage. In 2007 Wallace was a happy man, writing, married since 2004, for the first time, to the artist Karen Green, and teaching at Pomona College, one of the distinguished Claremont Colleges, where he had an endowed professorial chair that gave him pretty much free rein. After dinner at a Persian restaurant in Claremont one evening, he developed excruciating stomach pains that lasted several days. His doctor suspected a dire food interaction with Nardil, and suggested Wallace go off that outdated medication and try something newer. Wallace had already suspected for several months that Nardil was impeding the flow of The Pale King—though it evidently had not interfered with Infinite Jest—so the idea sounded promising. But then Wallace tried doing without any medication at all, and he landed in the hospital in the fall of 2007. After that he went on one drug after another but never really gave any of them the chance to be effective. Not wanting to foul his home, he tried suicide by overdose in a nearby motel, but survived. A course of twelve electroconvulsive treatments failed to work. He went back on Nardil; it did not kick in quickly enough. Not caring any more what he fouled, on September 12, 2008, he waited for his wife to leave for her gallery, wrote her a two-page note, and hanged himself on the patio of their Claremont home. He left a neat stack of manuscript pages in his garage office for his wife to find.

{ The Claremont Institute | Continue reading }

drugs, experience, ideas | March 18th, 2012 12:00 pm

The treatment of addiction and dependence on, and misuse of, alcohol and other drugs is one of the largest unmet needs in medicine today, so the development of new treatments is a pressing need. However, we have seen the development and use of different terminologies for different drug addictions, which confuses prescribers, users and regulators alike. Here we try to clarify terminology of treatment models based on the pharmacology of treatment agents. This editorial covers all drugs that are used for their pleasurable effects and which therefore can lead to harmful/hazardous use, dependence and addiction. These include nicotine, alcohol and abused prescription drugs such as benzodiazepines, as well as opioids and stimulants.

{ SAGE | Continue reading }

Linguistics, drugs, health | March 16th, 2012 4:10 pm

It is well known that in theory and in reality people cooperate more when then expect to interact over more repetitions, and when they care more about the future.

{ Overcoming Bias | Continue reading }

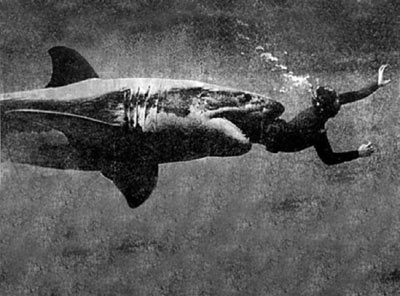

unrelated { Self-Piercing at Thailand Vegetarian Festival }

ideas, relationships | March 16th, 2012 3:39 pm

photo { Emma Hardy }

ideas, photogs | March 15th, 2012 8:11 am