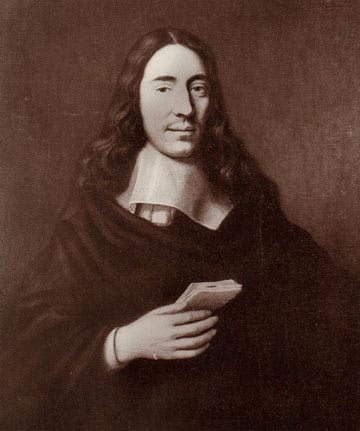

Bento de Spinoza was born on November 24, 1632, to a promi nent merchant family among Amsterdam’s Portuguese Jews. This Sephardic community was founded by former New Christians, or conversos—Jews who had been forced to convert to Catholicism in Spain and Portugal in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centu ries—and their descendants. After fleeing harassment by the Iberian Inquisitions, which doubted the sincerity of the conversions, many New Christians eventually settled in Amsterdam and a few other northern cities by the early seventeenth century. With its generally tolerant environment and greater concern for economic prosperity than religious uniformity, the newly independent Dutch Republic (and especially Holland, its largest province) offered these refugees an opportunity to return to the religion of their ancestors and re establish themselves in Jewish life. There were always conservative sectors of Dutch society clamoring for the expulsion of the “Portuguese merchants” in their midst.8 But the more liberal regents of Amsterdam, not to mention the more enlightened elements in Dutch society at large, were unwilling to make the same mistake that Spain had made a century earlier and drive out an economi cally important part of its population, one whose productivity and mercantile network would make a substantial contribution to the flourishing of the Dutch Golden Age.

The Spinoza family was not among the wealthiest of the city’s Sephardim, whose wealth was in turn dwarfed by the fortunes of the wealthiest Dutch. They were, however, comfortably well-off. Spinoza’s father, Miguel, was an importer of dried fruit and nuts, mainly from Spanish and Portuguese colonies. (…)

mainly from Spanish and Portuguese colonies. To judge both by his accounts and by the respect he earned from his peers, he seems for a time to have been a fairly successful businessman. (…)

Spinoza may have excelled in school, but, contrary to the story long told, he did not study to be a rabbi. In fact, he never made it into the upper levels of the educational program, which involved advanced work in Talmud. In 1649, his older brother Isaac, who had been helping his father run the family business, died, and Spinoza had to cease his formal studies to take his place. When Miguel died in 1654, Spinoza found himself, along with his other brother, Gabriel, a full-time merchant, running the firm Bento y Gabriel de Spinoza. He seems not to have been a very shrewd merchant, however, and the company, burdened by the debts left behind by his father, floundered under their direction. Spinoza did not have much of a taste for the life of commerce anyway. Financial success, which led to status and respect within the Portuguese Jewish community, held very little attraction for him. (…)

By the early to mid-1650s, Spinoza had decided that his future lay in philosophy, the search for knowledge and true happiness, not in the importing of dried fruit.

Around the time of his disenchantment with the mercantile life, Spinoza began studies in Latin and the classics. (…) Although distracted from business affairs by his studies and undoubtedly experiencing a serious weakening of his Jewish faith as he delved ever more deeply into the world of pagan and gentile letters, Spinoza kept up appearances and continued to be a mem ber in good standing of the Talmud Torah congregation through out the early 1650s. He paid his dues and communal taxes, and even made the contributions to the charitable funds that were ex pected of congregants.

And then, on July 27, 1656, the following proclamation was read in Hebrew before the ark of the Torah in the crowded synagogue on the Houtgracht: “The gentlemen of the ma’amad [the congregation’s lay governing board] hereby proclaim that they have long known of the evil opin ions and acts of Baruch de Spinoza. (…) Spinoza should be excommunicated and expelled from the people of Israel. By decree of the angels and by the command of the holy men, we excommunicate, expel, curse, and damn Baruch de Espinoza. (…) No one is to communicate with him, orally or in writing, or show him any favor, or stay with him under the same roof, or come within four cubits of his vicinity, or read any treatise composed or written by him.”

We do not know for certain why Spinoza was punished with such extreme prejudice. That the punishment came from his own community—from the congregation that had nurtured and edu cated him, and that held his family in high esteem—only adds to the enigma. Neither the herem itself nor any document from the period tells us exactly what his “evil opinions and acts” were sup posed to have been, or what “abominable heresies” or “monstrous deeds” he is alleged to have practiced and taught. He had not yet published anything, or even composed any treatise. Spinoza never refers to this period of his life in his extant letters and thus does not offer his correspondents (or us) any clues as to why he was expelled.

{ Steven Nadler, A Book Forged in Hell: Spinoza’s Scandalous Treatise and the Birth of the Secular Age, Chapter 1 | Continue reading }