beaux-arts

When you knew that it was over, were you suddenly aware, that the autumn leaves were turning to the color of her hair?

The Windmills of Your Mind, music written by Michel Legrand, with Alan Bergman and Marilyn Bergman; lyrics by Alan Bergman and Marilyn Bergman; from the 1968 film The Thomas Crown Affair.

Noel Harrison performed the song for the film score. It won the Academy Award for Best Original Song in 1969 (Harrison’s father, the British actor Rex Harrison, had performed the previous year’s Oscar-winning “Talk to the Animals”).

The opening two melodic sentences were adapted from Mozart’s second movement from his Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Viola and Orchestra.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading | Lyrics and guitar chord transcription | Listen | Download }

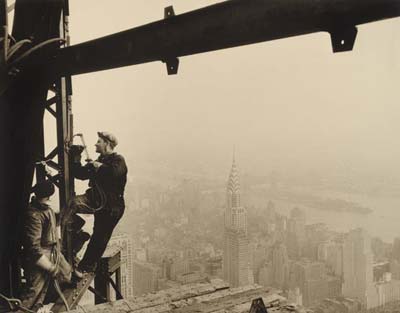

‘A hundred times have I thought New York is a catastrophe and 50 times: It is a beautiful catastrophe.’ –Le Corbusier

In late 1929, Alfred E. Smith, the leader of a group of investors erecting the Empire State Building, announced that they were increasing the height of the building to 1,250 feet from 1,050. Mr. Smith, a past governor of New York, denied that competition with the 1,046-foot-high Chrysler Building was a factor. “We are measuring its rise by principles of economic investment rather than spectacular standards,” he told The New York Times.

The extra 200 feet, it was announced, was to serve as a mooring mast for dirigibles so that they could dock in Midtown, rather than out in Lakehurst, N.J., the station used by the German Graf Zeppelin. Mr. Smith said that at the Empire State Building, airships like the Graf, almost 800 feet long, would “swing in the breeze and the passengers go down a gangplank”; seven minutes later they would be on the street.

But the Germans, who dominated dirigible technology, had not asked for a docking station, and passenger traffic on dirigibles was still minuscule. The mast camouflaged the quest for boasting rights to the world’s tallest building, an ambition to which it seemed indecent to admit.

photo { Lewis W. Hine, Welders on the Empire State Building, circa 1930 }

It must be a movement then, an actuality of the possible as possible

Beyond the practical experiences and impressions being held for ages from ancient times, the scientific observations and surveys indicate that psychopathological symptoms, especially those belonging to the bipolar mood disorder (bipolar I and II), major depression and cyclothymia categories occur more frequently among writers, poets, visual artists and composers, compared to the rates in the general population. Self-reports of writers and artists describe symptoms in their intensively creative periods which are reminiscent and characteristic of hypomanic states. Further, cognitive styles of hypomania (e.g. overinclusive thinking, richness of associations) and originality-prone creativity share many common as indicated by several authors.

Among the eminent artists showing most probably manic-depressive or cyclothymic symptoms were: E. Dickinson, E. Hemingway, N. Gogol, A. Strindberg, V. Woolf, Lord Byron (G. Gordon), J. W. Goethe, V. van Gogh, F. Goya, G. Donizetti, G. F. Händel, O. Klemperer, G. Mahler, R. Schumann, and H. Wolf. Based on biographies and other studies, brief descriptions are given in the present article on the personality character of Gogol; Strindberg, Van Gogh, Händel, Klemperer, Mahler, and Schumann.

Further example is the enigmatic silence and withdrawal from opera composing of Gioacchino Rossini (1792-1868), which is still a matter of various theories and explanations. Until his life of 37 years he composed 39 operas and lived almost another 40 years without composing any new one. Biographies show that severe depressive sufferings played a role in that withdrawal and silence, while in his juvenile years most probably hypomanic personality traits contributed to the extreme achievements and very fast composing techniques. Analysing the available biographies of Rossini and the character of music he composed (e.g. opera buffa, Rossini crescendo) strongly suggests the medical diagnosis of a bipolar affective illness.

Comparing to the general population, bipolar mood disorder is highly overrepresented among writers and artists. The cognitive and other psychological features of artistic creativity resemble many aspects of the hypomanic symptomatology. It may be concluded that bipolar mood traits might contribute to highly creative achievements in the field of art. At the same time, considering the risks, the need of an increased medical care is required.

Totally Enormous Extinct Dinosaurs Remix

download { CFCF’s mix at PS1 | Letherette’s mix | Phoenix, Wolfgang Amadeus Phoenix }

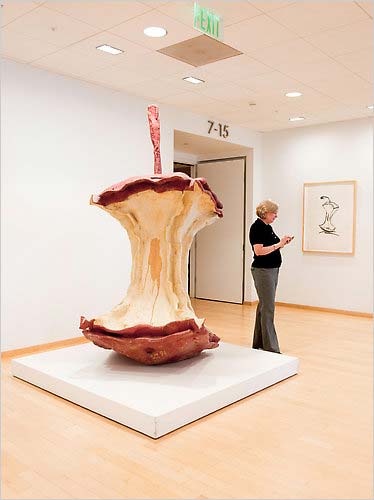

The alchemists

{ It was just another day at the Gap, the clothing chain, where for many years much of the extraordinary art collection of the company’s founders, Don and Doris Fisher, has been hidden away in these ground-floor rooms. Although the collection includes more than 1,100 works, mostly from the 1960s on, they have been seen by relatively few people: Gap employees, the occasional museum tour group and those in the upper echelons of the art world who have the right connections. News media coverage has always been tightly restricted, and Mr. Fisher, who directed the Gap for more than 40 years until his death at 81 last September, refused to give interviews about his holdings for most of that time. | NY Times | Continue reading }

How you’ll have a perfect orgasm and scream for more

Although the audio program Auto-Tune is best known for the singing-through-a-fan, robotic vocal style that has dominated pop radio in recent years with stars like Lady Gaga, T-Pain and countless others, Auto-Tune is in fact widely used in the studio and at concerts to make artists’ sound pitch-perfect.

“Quite frankly, [use of Auto-Tune] happens on almost all vocal performances you hear on the radio,” said Marco Alpert, vice president of marketing for Antares Audio Technologies, the company that holds the trademark and patent for Auto-Tune.

The beauty of Auto-Tune, Alpert said, is that instead of an artist having to sing take after take, struggling to get through a song flawlessly, Auto-Tune can clean up small goofs. (…)

Auto-Tune’s invention sprung from a quite unrelated field: prospecting for oil underground using sound waves. Andy Hildebrand, a geophysicist who worked with Exxon, came up with a technique called autocorrelation to interpret these waves. During the 1990s, Hildebrand founded the company that later became Antares, and he applied his tools to voices.

The recording industry pounced on the technology, and the first song credited (or bemoaned) for introducing Auto-Tune to the masses was Cher’s 1998 hit “Believe.”

Although a success with audio engineers, Auto-Tune remained largely out of sight until 2003 when rhythm and blues crooner T-Pain discovered its voice-altering effects.

‘Superman can fly high way up in the sky cause we believe he can.’ –Luther Vandross

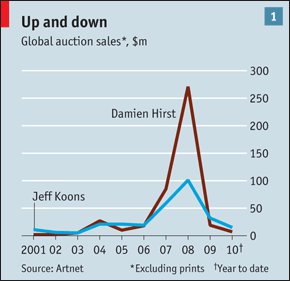

{ But who exactly bought what? Even Mr Hirst admits, “I’m still finding out.” Dealers acquired some works, but 81% of the buyers were private collectors purchasing directly. | How Damien Hirst grew rich at the expense of his investors | The Economist | full story }

{ The Art Damien Hirst Stole | more | Thanks Tim }

Shut your eyes and open your mouth

Italian scientists are to try to establish whether there really is such a phenomenon as Stendhal Syndrome — the giddiness, sweaty state of confusion and even hallucinations that are supposedly aroused when one looks at great works of art.

The condition is named after the 19th-Century French author Stendhal, who wrote of feeling utterly overwhelmed by the Renaissance masterpieces he saw during a trip to Florence in 1817.

{ Independent.ie | Continue reading | Thanks Tim }

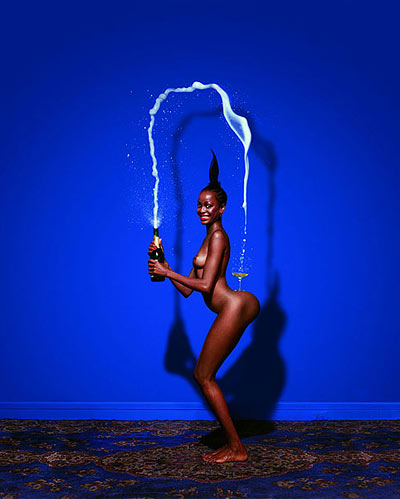

photo { Tookie Smith photographed by Jean-Paul Goude, 70s }

You call that an argument? No, that’s a fact. The argument’s leaning over there against the door jamb.

{ Pierre Huyghe, Third Memory, 1999 | Third Memory takes as its point of departure a bank robbery committed by John Woytowicz in Brooklyn in 1972; three years later the crime became the subject of Sidney Lumet’s film Dog Day Afternoon, starring Al Pacino. Huyghe tracked down Woytowicz and asked him to retell the story. Using a two-channel video projection, a television interview, and posters, Huyghe builds from a “first memory” of the original crime to a “second memory” with the film’s recreation of that crime, to arrive at a “third memory,” a rich blurring of the documented and the imagined. | San Francisco Museum of Modern Art | University of Virginia | Art Museum }

Second as a flow, and third for their meaning

It made me wonder if genius can be defined by the degree to which something intellectual can be felt as a physical experience.

For example, most people feel something when they listen to music. But I suspect gifted musicians feel it in an entirely different way than I do. I could never memorize all the notes in a song because for me it would be an exercise in rote memorization. For someone gifted in music, memorizing a song is easier because such a person would remember how each part felt. Feelings create memories more easily than intellectual experiences. The stronger the feeling, the easier the memory.

‘A happy marriage is the union of two good forgivers.’ –Robert Quillen

When you say “I’m not going to participate in your art because I think it’s obscene” on the one hand you’re slapping someone in the face — what you think of as beautiful, I think should not be seen but, to be honest, on the other hand you’re often validating them. If people in the main-stream hadn’t freaked out about Robert Maplethorpe you’d probably have no idea who he was, unless you were prone to reading the fine print on the backs of Patti Smith albums. So complaints about art help define it. In part you know if you should like it because of who hates it. And it’s also free advertising.

{ Kyle Cassidy | Continue reading | Thanks Richard! }

Wake this time next year

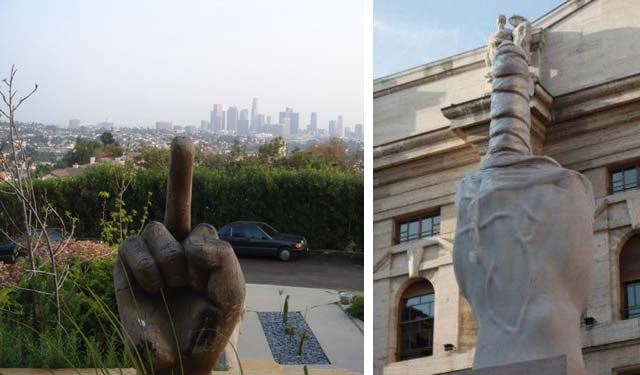

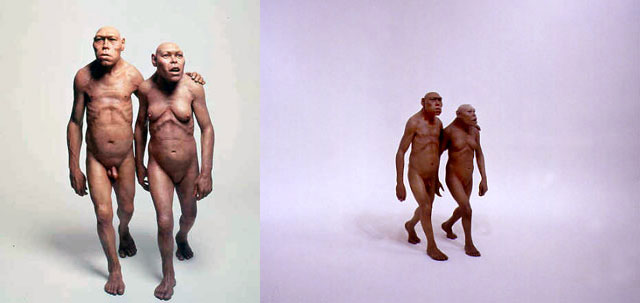

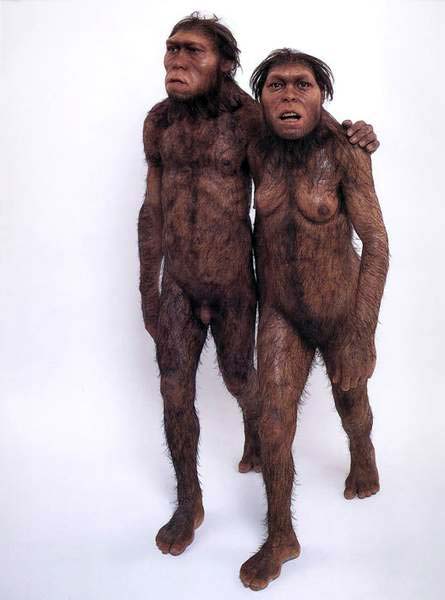

{ 1. Unsourced image | 2. Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 2000 }

Let’s just go walking in the rain

For jazz fans, nothing could be more tantalizing than the excerpts made available by the National Jazz Museum in Harlem of newly discovered recordings from the 1930s and ’40s. Nearly 1,000 discs containing performances by masters like Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Billie Holiday and the long-neglected Herschel Evans suddenly re-emerged when the son of the audio engineer, William Savory, sold them to the museum.

The museum is doing its best to clean up and digitize the recordings. But because of the way copyright laws work, excerpts may be all that fans can hear for some time. The museum paid for the discs, but cannot distribute the music until it has found a way to compensate the estates of the musicians, many of which may be very difficult to track down after all these decades. Hawkins’s saxophone solo on “Body and Soul” may be reason enough for Congress to revisit this issue and free historical documents from excessive legal fetters.

Copyright laws are designed to ensure that authors and performers receive compensation for their labors without fear of theft and to encourage them to continue their work. The laws are not intended to provide income for generations of an author’s heirs, particularly at the cost of keeping works of art out of the public’s reach.

The Savory collection, like other sound recordings made before 1972, is covered by a patchwork of state copyright and piracy laws that in some cases allow copyrights to remain until the year 2067.

Yes, bread of angels it’s called. There’s a big idea behind it, kind of kingdom of God is within you feel.

“The problem is all inside your head”, she said to me. The answer is easy if you take it logically. (…) She said it grieves me so to see you in such pain, I wish there was something I could do to make you smile again. I said I appreciate that. (…) She said why don’t we both just sleep on it tonight, and I believe in the morning you’ll begin to see the light. And then she kissed me and I realized she probably was right.

{ Paul Simon, Fifty Ways to Leave Your Lover, 1975 | Lyrics }

50 Ways to Leave Your Lover is a 1975 hit song by Paul Simon, from his album Still Crazy After All These Years. It became number one on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 on February 7, 1976, and remained there for three weeks.

Written after Simon’s divorce from first wife Peggy Harper, the song is a mistress’s humorous advice to a husband on ways to end a relationship. Studio drummer Steve Gadd created the unique drum beat that became the hook and color for the song consisting of an almost military beat. The song was recorded in a small New York City studio on Broadway.

{ Paul Simon, live on BBC TV, December 27, 1975 }

‘A change in the weather is sufficient to recreate the world and ourselves.’ –Marcel Proust

{ Levitation & Paco Fernandez feat. Cathy Battistessa, Oh Home, 1999 }

{ The Style Council, Mick’s Company, 1984 | B-side of the single My Ever-Changing Moods }

{ Smiley Culture, Shan A Shan, 1984 }