Just look through it. There can be no two opinions on the matter.

{ Ty Segall, So Alone, 2008 | Thanks Douglas }

{ Ty Segall, So Alone, 2008 | Thanks Douglas }

Astrophysicists think they know how to destroy a black hole. The puzzle is what such destruction would leave behind.

The idea of a body so massive that its escape velocity exceeds the speed of light dates back to the English geologist John Michell who first considered it in 1783. In his scenario, a beam of light would travel away from the massive body until it reached a certain height and then returned to the surface.

Modern thinking about black holes is somewhat different, not least because special relativity tells us that the speed of light is a universal constant. The critical concept that physicists focus on today is the event horizon: a theoretical boundary in space through which light and other objects can pass in one direction but not in the other. Since light cannot escape, the event horizon is what makes a black hole black.

The event horizon is somewhat of a disappointment to many astrophysicists because the interesting physics, the stuff beyond the known laws of the universe, all occurs inside it and is therefore hidden from us.

What physicists would like, therefore, is way to get rid of the event horizon and expose the inner workings to proper scrutiny. Doing this would destroy the black hole but reveal something far more bizarre and exotic.

Today, Ted Jacobson at the University of Maryland and Thomas Sotiriou and the University of Cambridge explain how this might be done in an entertaining and remarkably accessible account of the challenge.

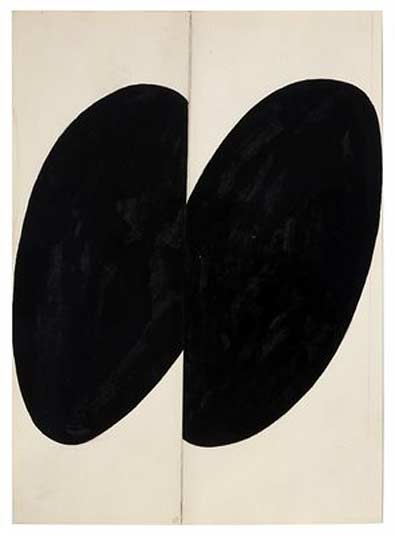

artwork { Ellsworth Kelly, Black Forms, 1955 | ink, graphite and collage on paper }

If you’re having trouble getting a date, French researchers suggest that picking the right soundtrack could improve the odds. Women were more prepared to give their number to an ‘average’ young man after listening to romantic background music, according to research that appears today in the journal Psychology of Music, published by SAGE.

There’s plenty of research indicating that the media affects our behaviour. Violent video games or music with aggressive lyrics increase the likelihood of aggressive behaviour, thoughts and feelings – but do romantic songs have any effect? This question prompted researchers Nicolas Guéguen and Céline Jacob from the Université de Bretagne-Sud along with Lubomir Lamy from Université de Paris-Sud to test the power of romantic lyrics on 18-20 year old single females. And it turns out that at least one romantic love song did make a difference.

{ DJ Fly, DMC World Champion 2008 }

{ Lisa Shaw, Growing apart }

{ Felt w/ elizabeth fraser from Cocteau Twins, Primitive Painters }

“While I remained at Paris, near you, my father,” said Fleur-de-Marie, “I was so happy, oh! so completely happy, that those delicious days would not be too well paid for by years of suffering. You see I have at least known what happiness is.”

“During some days, perhaps?”

“Yes, but what pure and unmingled felicity! Love surrounded me then, as ever, with the tenderest care. I gave myself up without fear to the emotions of gratitude and affection which every moment raised my heart to you. The future dazzled me: a father to adore, a second mother to love doubly.

{ Eugene Sue, Mysteries of Paris, 1842-1843 | Continue reading }

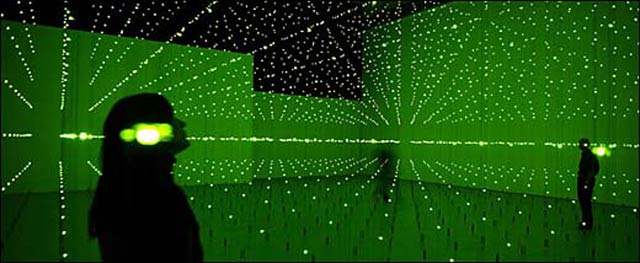

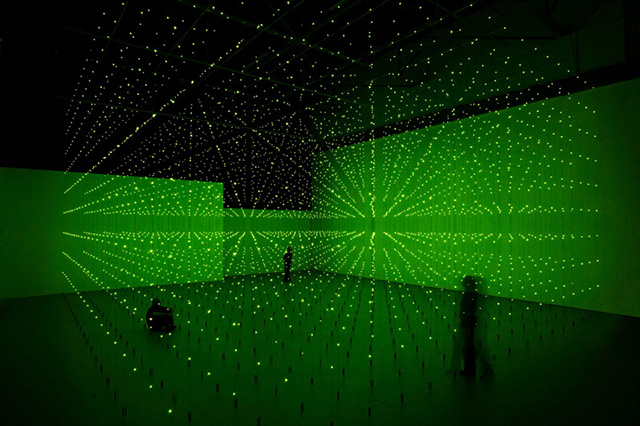

…being green really is tough, so tough that the color itself fails dismally. The cruel truth is that most forms of the color green, the most powerful symbol of sustainable design, aren’t ecologically responsible, and can be damaging to the environment.

“Ironic, isn’t it?” said Michael Braungart, the German chemist who co-wrote “Cradle to Cradle,” the best-selling sustainable design book, and co-founded the U.S. design consultancy McDonough Braungart Design Chemistry. “The color green can never be green, because of the way it is made. It’s impossible to dye plastic green or to print green ink on paper without contaminating them.”

This means that green-colored plastic and paper cannot be recycled or composted safely, because they could contaminate everything else. The crux of the problem is that green is such a difficult color to manufacture that toxic substances are often used to stabilize it.

Take Pigment Green 7, the commonest shade of green used in plastics and paper. It is an organic pigment but contains chlorine, some forms of which can cause cancer and birth defects. Another popular shade, Pigment Green 36, includes potentially hazardous bromide atoms as well as chlorine; while inorganic Pigment Green 50 is a noxious cocktail of cobalt, titanium, nickel and zinc oxide.

If you look at the history of green, it has always been troublesome. Revered in Islamic culture for evoking the greenery of paradise, it has played an accident-prone role in Western art history. From the Italian Renaissance to 18th-century Romanticism, artists struggled over the centuries to mix precise shades of green paint, and to reproduce them accurately. (…)

Green even has a toxic history. Some early green paints were so corrosive that they burnt into canvas, paper and wood. Many popular 18th- and 19th-century green wallpapers and paints were made with arsenic, sometimes with fatal consequences. One of those paints, Scheele’s Green, invented in Sweden in the 1770s, is thought by some historians to have killed Napoleon Bonaparte in 1821, when lethal arsenic fumes were released from the rotting green and gold wallpaper in his damp cell on the island of Saint Helena.

images { Erwin Redl, Matrix II, 2000 | light-emitting diode installation }

{ Bill Evans, 1966}

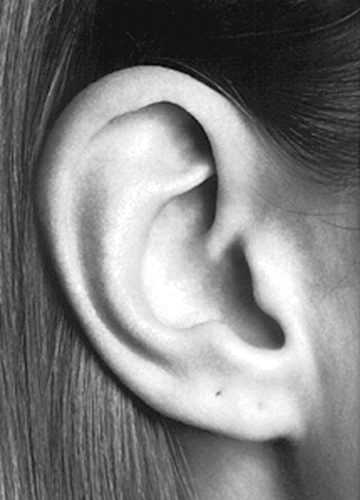

An earworm is a song going around in your head that you can’t get rid of. Some claim that earworms are like a cognitive itch, we scratch them by repeating the tune over and over in our heads.

In new research, Beaman & Williams (2010) asked 103 participants aged 15-57 all about their earworm experiences. Here’s what they found:

• Many earworms were pop songs, although adverts and TV/film themes and video game tunes were also mentioned.

• One-third generally experienced the chorus or refrain over and over again, but almost half said that it varied.

• 10% of participants reported that earworms stopped them doing other things.

• Contrary to popular belief those with musical training were no more likely to experience earworms. (…)

For most of us earworms are relatively untroubling. And if you are tempted to moan then just be thankful you’re not the 21-year-old described in a case report by Praharaj et al. (2009). This man had had music from Hindi films going around in his head against his will for between 2 and 45 minutes at a time, up to 35 times a day, for five years. Unfortunately even powerful drugs couldn’t stop the music.

{ PsyBlog | Continue reading }

It sometimes feel like our minds are not on the same team as us. I want to go to sleep, but it wants to keep me awake rerunning events from my childhood. I want to forget the lyrics from that stupid 80s pop song but it wants to repeat them over and over again ad nauseam. (…)

Perpetual thoughts of food drive people to obesity, persistent negative thoughts cue depression and traumatic events push back into consciousness to be relived over and over again. (…)

Although it makes perfect intuitive sense to try and suppress unwanted thoughts, unfortunately the very process we use to do this contains the seeds of its own destruction. The more we try and push intrusive thoughts down, the more they pop back up, stronger than ever.

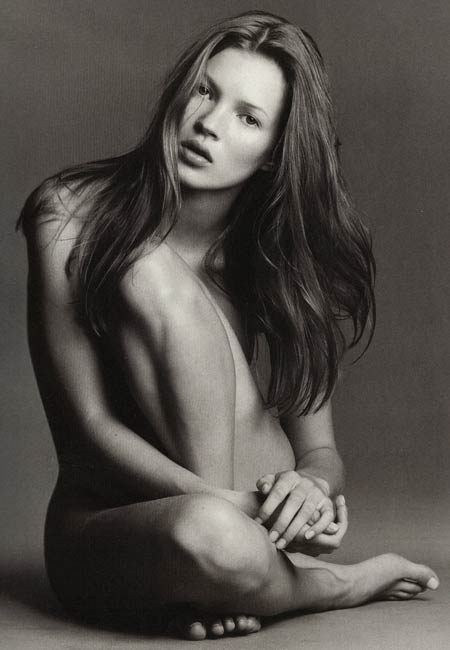

photos { Kate Moss photographed by Michael Thompson, 1993 }

related { Kate Moss shows off six piercings after visit to tattoo parlour, 2009 }

bonus:

Emily Haines, lead singer of the Canadian band Metric, sings on “Help, I’m Alive,” the hit single from last year’s Fantasies. It’s not so much a rhetorical question as it is a brave reclamation of self-purpose: it’s Haines flipping the bird at the imagined glass ceilings and self-doubt she condemned on previous records. Any why shouldn’t she? Even in a fractured musical climate that doesn’t invite or invent figureheads like it once did, Emily Haines has recently been elevated to the role of indie pop’s cool big sister. At a recent sold-out show at New York City’s Terminal 5, she prowled the stage with the devastating cool of a feline predator. (…)

NIKA: What about the Lady Gaga effect?

HAINES: I can honestly say it makes me laugh and I really don’t care. It has nothing to with music. I mean, it’s fascinating. Show up wearing Kermit the Frog, why not? It’s fun and she has a good time. It has nothing to do with the world that I live in.

Over the past year or so, Stanley Fish has occasionally devoted his New York Times blog to the notion that, as he put it recently, higher education is “distinguished by the absence” of a relationship between its activities and any “measurable effects in the world.” (…) “The humanities, Fish claimed, do not have an extrinsic utility—an instrumental value—and therefore cannot increase economic productivity, fashion an informed citizenry, sharpen moral perceptions, or reduce prejudice and discrimination. (…)

The real issue, as Fish concedes, is not whether art, music, history, or literature has instrumental value, but whether academic research into those subjects has such value. Few would claim that art and literature have no intrinsic worth, and very few would claim that they possess no measurable utility. Students at Harvard Medical School, for instance, like students at a growing number of medical schools across the country, now take art courses. Studying works of art, researchers believe, makes students more observant, more open to complexity, and more-flexible thinkers—in short, better doctors. (…)

In fact, humanities research already has instrumental value. That value, however, is rarely immediate or predictable. Consider the following examples: (…)

“Stream of consciousness” was a phrase first used by William James, in 1890, to describe the flow of perception in the human mind. It was later adopted by literary critics like Melvin J. Friedman, author of the 1955 book Stream of Consciousness: A Study in Literary Method, who used the term to explain the unedited forms of interior monologue common in modernist novels of the 1920s. However, by his own acknowledgment, Knuth’s innovations were most clearly influenced by the work of the Belgian computer scientist Pierre-Arnoul de Marneffe, who was in turn inspired by Arthur Koestler’s 1967 book, The Ghost in the Machine, on the structure of complex organisms. And that book took its title and its point of departure from a key piece of 20th-century humanities research, Gilbert Ryle’s The Concept of Mind (1949), which challenged Cartesian dualism.

There is, then, a visible legacy of utility that begins with research into Descartes and leads to important innovations in computer science. (…)

Examples of research with unclear instrumental value abound, in all disciplines. Scientists at the University of British Columbia have found that working in front of a blue wall (and not a red one) improves creative thinking.

{ Stephen J. Mexal/The Chronicle of Higher Education | Continue reading }

Alberto Giacometti’s six-foot-tall bronze Walking Man I sold at Sotheby’s London in February 2010 for the equivalent of $104.3 million, and was briefly (until overtaken this month by a Picasso) the most expensive artwork ever sold at auction. It remains, by far, the most expensive work available in multiple examples. The sculpture, cast by the artist himself in 1961, was reportedly bought by Lily Safra, widow of banker Edmund Safra. (…)

But by most people’s standards it is a very large sum of money; and in relation to the production cost of the sculpture it is an absurdly large sum of money. To make a copy of Walking Man I today (I am told by Morris Singer Foundry, which does much casting for artists in the UK) would cost in the region of $25,000, including the price of the bronze. If we allow for Giacometti’s time to make the piece, it does not substantially alter the enormity of the disparity between production cost and market price. Given that the sculpture exists in an edition of six, it would seem that, back in the early 1960s, Giacometti single-handedly created more than a half a billion dollars of goods, at today’s prices, in at most a few weeks. (…) Writing about the Giacometti sale, the Australian journalist Andrew Frost posed the question that no doubt many people ask themselves even if they do not utter it out loud: “Since the material value of art is negligible, we’re paying for something — but what?”

Pablo Picasso, legend has it, had an answer to this: you are paying for “a lifetime of experience.” But this explanation fails when we consider the market in work by Picasso himself. The most expensive works by Picasso that have been sold at auction are the 1932 Nude, Green Leaves and Bust, purchased recently for $106.5 million; and a 1905 Rose Period painting, Garcon a la Pipe, which was auctioned for $104.2 million in 2004. Allowing for inflation, the Garcon cost more in real terms than the Nude. Picasso, born in 1881, was roughly 24 years old when he painted it, and he eventually lived to 91: the art he produced in his old age, with a “lifetime of experience” behind him, is worth less, not more.

A sense of the disconnect between the production cost and market price of artworks has already become a part of modern consciousness. (…)

Recently a number of books have been published by economists who aim to reveal the mechanism that leads to the formation of staggering prices for art, especially modern art. As part of their analyses, these economists have attempted to define exactly what the quality or qualities are that collectors pay for. Among these books are Don Thompson’s The $12 Million Stuffed Shark, David W. Galenson’s Artistic Capital, and Olav Velthuis’s Talking Prices. Of course, theories of art can be more sophisticated than those proposed in the above books, but as a rule they don’t directly address the question “What are we paying for?” By applying the principle of Follow The Money, maybe we can arrive at an insight into art itself.

Thompson’s theory is that the price of the preserved shark to which his title alludes (a work by Damien Hirst) and of other expensive works of contemporary art is a reflection of “brand equity” produced by marketing and publicity. He compares explicitly the purchase of a “branded” artwork, i.e. one blessed by the gallery-auction-museum-press apparatus, to the purchase of a Louis Vuitton handbag, and suggests that branding is relied upon by buyers as a substitute for their own judgment, about which they feel insecure.

photo { Isabelle Pateer }

Ever since ancient times, scholars have puzzled over the reasons that some musical note combinations sound so sweet while others are just downright dreadful. The Greeks believed that simple ratios in the string lengths of musical instruments were the key, maintaining that the precise mathematical relationships endowed certain chords with a special, even divine, quality. Twentieth-century composers, on the other hand, have leaned toward the notion that musical tastes are really all in what you are used to hearing.

Now, researchers reporting online on May 20th in Current Biology, a Cell Press publication, think they may have gotten closer to the truth by studying the preferences of more than 250 college students from Minnesota to a variety of musical and nonmusical sounds. (…)

The researchers’ results show that musical chords sound good or bad mostly depending on whether the notes being played produce frequencies that are harmonically related or not. Beating didn’t turn out to be as important. Surprisingly, the preference for harmonic frequencies was stronger in people with experience playing musical instruments. In other words, learning plays a role—perhaps even a primary one, McDermott argues.

{ 50 Cent, Hate It Or Love It, G-Unit remix}

{ Nightcommunication EP | Andrea Gemolotto, Leo Mas, Sergio Portaluri }

{ The Smiths, This Night Has Opened My Eyes }

{ Martha Argerich plays Ravel, Jeux d’eau }

Green Buildings: Dow says many buildings are actually getting less efficient

Mike Kontranowski, Strategic Marketing Manager of Dow Building Solution’ Thermax brand of rigid insulating board, presented a sobering analysis of the direction of building efficiency during the Summit. Although buildings of all types have become more energy efficient on a per square foot basis for the past 50 years, many buildings constructed over the past decade have bucked the trend and have begun regressing on energy efficiency. This reversal comes despite newfound interest in “green building” among governments, occupants, and the building owners themselves, and despite the plethora of insulation, window, equipment, and other devices that yield far greater efficiencies. More surprisingly, many of the buildings are LEED (Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design) certified, because energy efficiency is only one of many metrics that accrue points needed for certification.

The proximate cause of the backslide in efficiency is a switch to less expensive aluminum wall studs in place of wood or block in recent years. Because aluminum is such a good conductor of heat, walls that are otherwise well-insulated – with insulation batts installed between the studs – see an overall insulating R-value of the wall drop in half, from 11 or more to 5. Thermal images of walls are particularly poignant, showing relatively small amounts of heat escaping from between the studs, while the studs themselves were lit up like Christmas trees.

{ Lux Research Analyst Blog | Continue reading | via Josh Wolfe }

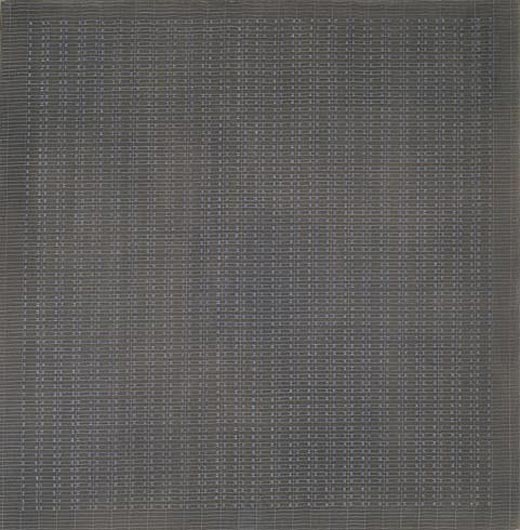

{ Agnes Martin, The Tree, 1964 | oil and pencil on canvas | Of the genesis of her paintings, Martin said, “When I first made a grid I happened to be thinking of the innocence of trees and then this grid came into my mind and I thought it represented innocence, and I still do.” }

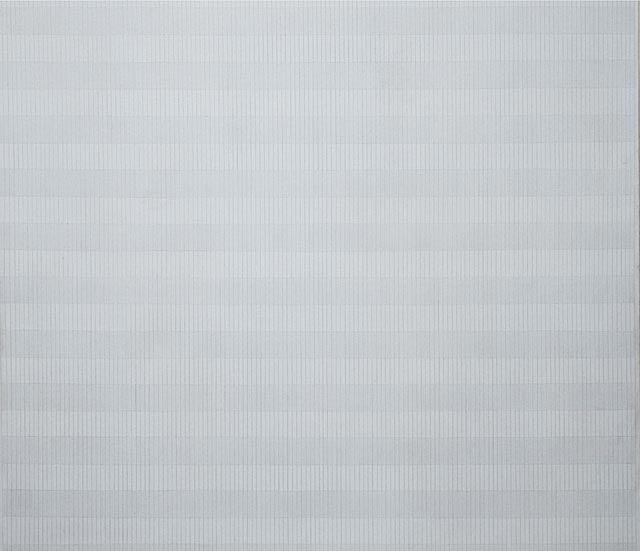

{ Agnes Martin, White Flower, 1960 | oil on canvas }

{ Agnes Martin Interview, 1997 | via Doug/Ed }

vaguely related { Paintings worth up to $613 million stolen in Paris. British art crime investigator Dick Ellis, director of Art Management Group, said: “If these estimates of the value are true then this could be the biggest theft in history. | more }