In the late 1960s and ‘70s, working with the New York City Planning Commission, the sociologist William H. Whyte conducted groundbreaking granular studies of the city’s public spaces, spending hours filming and photographing and taking notes about how people behave in public. Where do they like to sit? Where do they like to stand? When they bump into people they know, how long do their conversations last? […]

Whyte and his acolytes formulated conclusions that were, for their time, counterintuitive. For example, he discovered that city people don’t actually like wide-open, uncluttered spaces. Despite the Modernist assumption that what harried urban people need are oases of nature in the city, if you bother to watch people, you see that they tend to prefer narrow streets, hustle and bustle, crowdedness. Build a high-rise with an acre of empty plaza around it, and the plaza may seem desolate, even dangerous. People will avoid it. If you want people to linger, he wrote, give them seating — but not just benches, which make it impossible for people to face one another. Movable chairs can be better. Also: Never cordon off a fountain.

[…]

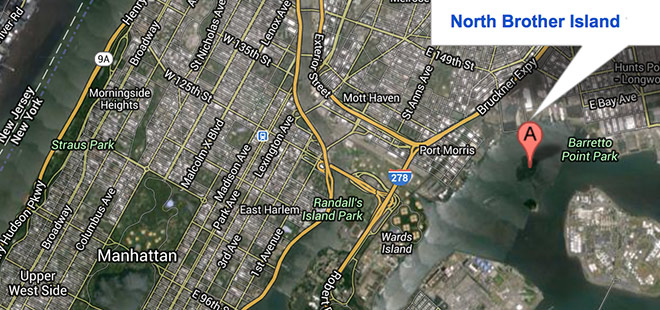

For his dissertation at the University of Toronto, Hampton studied an extraordinary early experiment in wired living. In the mid-1990s, a consortium that included IBM and Apple helped raise more than $100 million to turn a new suburban development in Newmarket, Ontario, a Toronto suburb, into the neighborhood of the future. As houses went up, more than half of them got high-speed Internet (this in the age of dial-up), advanced browser software for their computers, a tool for videoconferencing between houses and a Napster-like tool for music sharing. He treated the other homes as a control group. From October 1997 through August 1999, Hampton lived in a basement apartment in the new development, observing and interviewing his neighbors.

Hampton found that, rather than isolating people, technology made them more connected. […] [T]hey were much more successful at addressing local problems, like speeding cars and a small spate of burglaries. They also used their Listserv to coordinate offline events, even sign-ups for a bowling league. Hampton was one of the first scholars to marshal evidence that the web might make people less atomized rather than more.

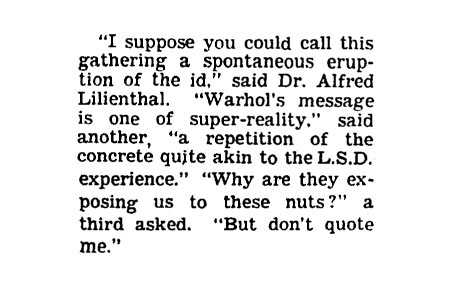

Hampton crudely summarized his former M.I.T. colleague Sherry Turkle’s book “Alone Together.” “She said: ‘You know, today, people standing at a train station, they’re all talking on their cellphones. Public spaces aren’t communal anymore. No one interacts in public spaces.’ I’m like: ‘How do you know that? We don’t know that. Compared to what? Like, three years ago?’ ”

Turkle said that her decades of observation are pretty conclusive: “When you watch a mother texting as she pushes a stroller — and I follow that mother for blocks, I walk alongside — you know it. You know that the streetscape used to include mothers who spoke to their children.”

[…]

According to Hampton, our tendency to interact with others in public has, if anything, improved since the ‘70s. The P.P.S. films showed that in 1979 about 32 percent of those visited the steps of the Met were alone; in 2010, only 24 percent were alone in the same spot. When I mentioned these results to Sherry Turkle, she said that Hampton could be right about these specific public spaces, but that technology may still have corrosive effects in the home: what it does to families at the dinner table, or in the den. Rich Ling, a mobile-phone researcher in Denmark, also noted the limitations of Hampton’s sample. “He was capturing the middle of the business day,” said Ling, who generally admires Hampton’s work. For businesspeople, “there might be a quick check, do I have an email or a text message, then get on with life.” Fourteen-year-olds might be an entirely different story.

{ NY Times | Continue reading | Thanks Jane JL! }