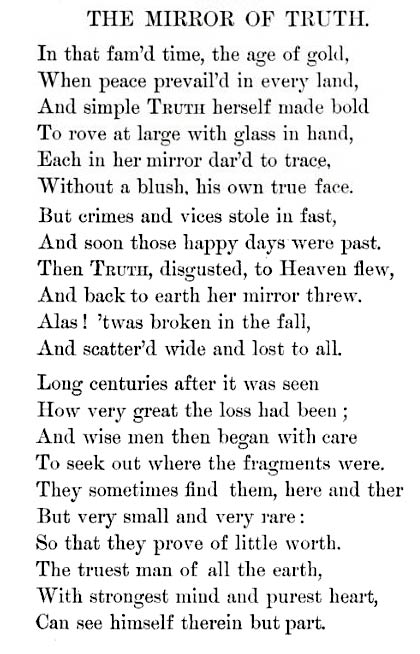

We are still living under the reign of logic: this, of course, is what I have been driving at. But in this day and age logical methods are applicable only to solving problems of secondary interest. The absolute rationalism that is still in vogue allows us to consider only facts relating directly to our experience. Logical ends, on the contrary, escape us. It is pointless to add that experience itself has found itself increasingly circumscribed. It paces back and forth in a cage from which it is more and more difficult to make it emerge. It too leans for support on what is most immediately expedient, and it is protected by the sentinels of common sense. Under the pretense of civilization and progress, we have managed to banish from the mind everything that may rightly or wrongly be termed superstition, or fancy; forbidden is any kind of search for truth which is not in conformance with accepted practices. It was, apparently, by pure chance that a part of our mental world which we pretended not to be concerned with any longer — and, in my opinion by far the most important part — has been brought back to light. For this we must give thanks to the discoveries of Sigmund Freud. On the basis of these discoveries a current of opinion is finally forming by means of which the human explorer will be able to carry his investigation much further, authorized as he will henceforth be not to confine himself solely to the most summary realities.

{ André Breton, Manifesto of Surrealism, 1924 | Continue reading }

Surrealism had the longest tenure of any avant-garde movement, and its members were arguably the most “political.” It emerged on the heels of World War I, when André Breton founded his first journal, Literature, and brought together a number of figures who had mostly come to know each other during the war years. They included Louis Aragon, Marc Chagall, Marcel Duchamp, Paul Eluard, Max Ernst, René Magritte, Francis Picabia, Pablo Picasso, Phillippe Soupault, Yves Tanguey, and Tristan Tzara. Some were “absolute” surrealists and others were merely associated with the movement, which lasted into the 1950s. (…)

André Breton was its leading light, and he offered what might be termed the master narrative of the movement.

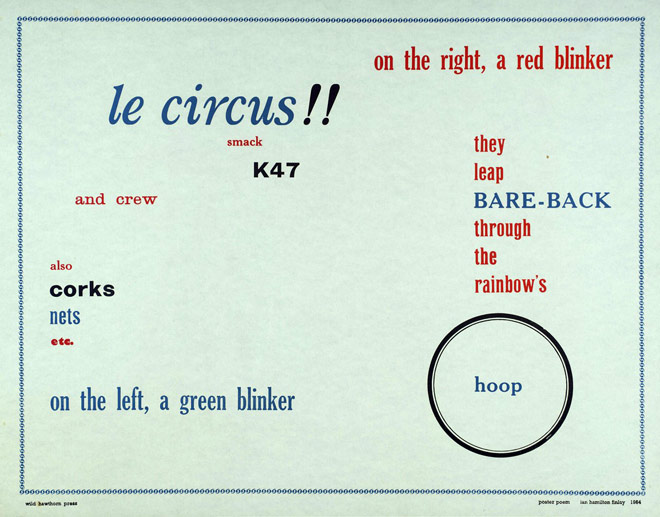

No other modernist trend had a theorist as intellectually sophisticated or an organizer quite as talented as Breton. No other was [as] international in its reach and as total in its confrontation with reality. No other [fused] psychoanalysis and proletarian revolution. No other was so blatant in its embrace of free association and “automatic writing.” No other would so use the audience to complete the work of art. There was no looking back to the past, as with the expressionists, and little of the macho rhetoric of the futurists. Surrealists prized individualism and rebellion—and no other movement would prove so commercially successful in promoting its luminaries. The surrealists wanted to change the world, and they did. At the same time, however, the world changed them. The question is whether their aesthetic outlook and cultural production were decisive in shaping their political worldview—or whether, beyond the inflated philosophical claims and ongoing esoteric qualifications, the connection between them is more indirect and elusive.

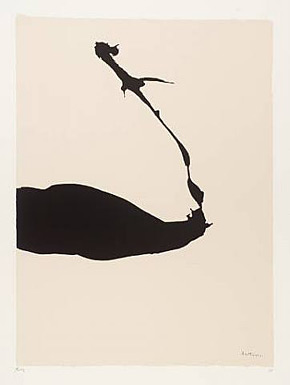

Surrealism was fueled by a romantic impulse. It emphasized the new against the dictates of tradition, the intensity of lived experience against passive contemplation, subjectivity against the consensually real, and the imagination against the instrumentally rational. Solidarity was understood as an inner bond with the oppressed.

{ Logos | Continue reading }