olfaction

By conveying cues of their current fertility, females can provide valuable reproductive information to conspecifics. Our closest relatives, non-human primates, employ diverse strategies, including olfactory cues from the anogenital region, to communicate information about female fertility. While their shared phylogeny with humans suggests that analogous olfactory cues may have been preserved in modern women, empirical evidence is lacking.

In a comprehensive two-fold approach, we investigated fertility-related shifts in the chemical composition of women’s vulvar volatiles as well as men’s ability to perceive them. We collected vulvar odour from 28 naturally cycling women […]

Simulating a first encounter, 139 men evaluated a total of 274 vulvar odour samples from 28 women, collected on different cycle days. […]

men’s attraction to vulvar odour was not significantly predicted by female fertility. Overall, our data suggests a relatively low retention of chemical fertility cues in vulvar odour of modern women.

{ Evolution and Human Behavior | Continue reading }

hormones, olfaction, relationships | August 12th, 2025 3:55 am

When you’re smelling the air while outside, you’re taking in a complicated bouquet of molecules floating through the atmosphere. But when the smell follows you inside on your clothes and hair, it’s made up largely of two compounds.

The first is ozone […] “That metallic smell that you’re smelling is actually an ozone smell” […] ozone is composed of three oxygen atoms, making it highly reactive. This makes it easy for ozone to stick into the porous surfaces of your clothes and hair.

The second scent is geosmin, a natural compound with a richer, earthy smell. If you like the smell of rain, also known as petrichor, geosmin is the main compound responsible for this smell. […] “Humans can smell geosmin better than sharks can smell blood in the water” […] Anthropologists believe humans developed this elevated perception to help our ancestors literally sniff out water, Elliott said, by identifying it underground or predicting rainfall. […]

On the molecular level, smells take the form of odor molecules detected by our noses’ olfactory sensory neurons. That means that the smell of the outdoors is genuine traces from the world around us — particles of dirt, air, plant matter and bacteria — that linger on us. Smell molecules often get tangled or attached on your skin, clothes and hair. […]

Herz suggests pregnant women, and parents in general, perceive their sense of smell to be stronger, and find many smells especially intense. This can be attributed to a general hyper vigilance. According to the NIH, smell sensitivity tests reveal a negligible difference in olfactory ability before, after or during pregnancy.

The human nose can detect at least 1 trillion odors. But being able to name them all is a notoriously difficult skill. The prestigious Givaudan Perfumery School in Paris asks students to memorize 500 fragrance components within their first year; career perfumers like Elliott might be able to possess and memorize thousands.

{ Washington Post | Continue reading }

evolution, olfaction | May 4th, 2025 10:05 am

NYC man sells fart for $85, cashing in on NFT craze […] Ramírez-Mallis and his fellow farters compiled the recordings into a 52-minute “Master Collection” audio file. Now, the top bid for the file is currently $183. Individual fart recordings are also available for 0.05 Ethereum, or about $85 a pop.

{ NY Post | Continue reading }

unrelated { Illegal Content and the Blockchain }

cryptocurrency, haha, noise and signals, olfaction | March 19th, 2021 6:53 am

All primates, including humans, engage in self-face-touching at very high frequency. The functional purpose or antecedents of this behaviour remain unclear. In this hybrid review we put forth the hypothesis that self-face-touching subserves self-smelling. […] Although we speculate that self-smelling through self-face-touching is largely an unconscious act, we note that in addition, humans also consciously smell themselves at high frequency.

{ PsyArXiv | Continue reading }

photo { Olivia Locher }

faces, olfaction | March 10th, 2020 9:56 am

First of all, I can remember very specific odors in extraordinary detail pretty much indefinitely. Moreover, I can conjure the memory of these odors exactly and at will. I have it on excellent authority from several researchers at the Monell Chemical Senses Center that this is a very rare capacity. […]

Secondly, I can mentally and very accurately forecast how the perceived odor of any given substance will change at various levels of concentration. […]

Thirdly and largely because of the two previously mentioned strange abilities, I can imagine discrete odors and know what will happen when I combine and arrange them while adjusting their concentrations – entirely in my head without even opening a bottle or picking up a pipette.

{ CB I Hate Perfume | Continue reading | Thanks Tim }

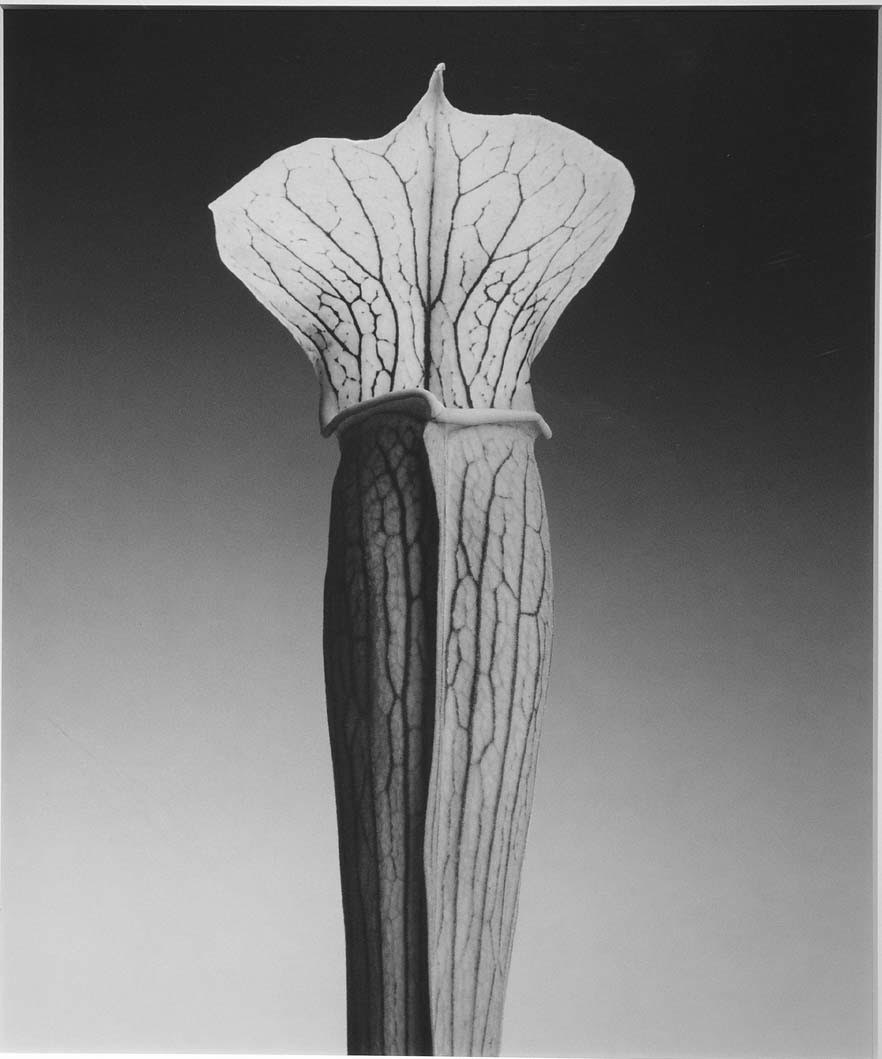

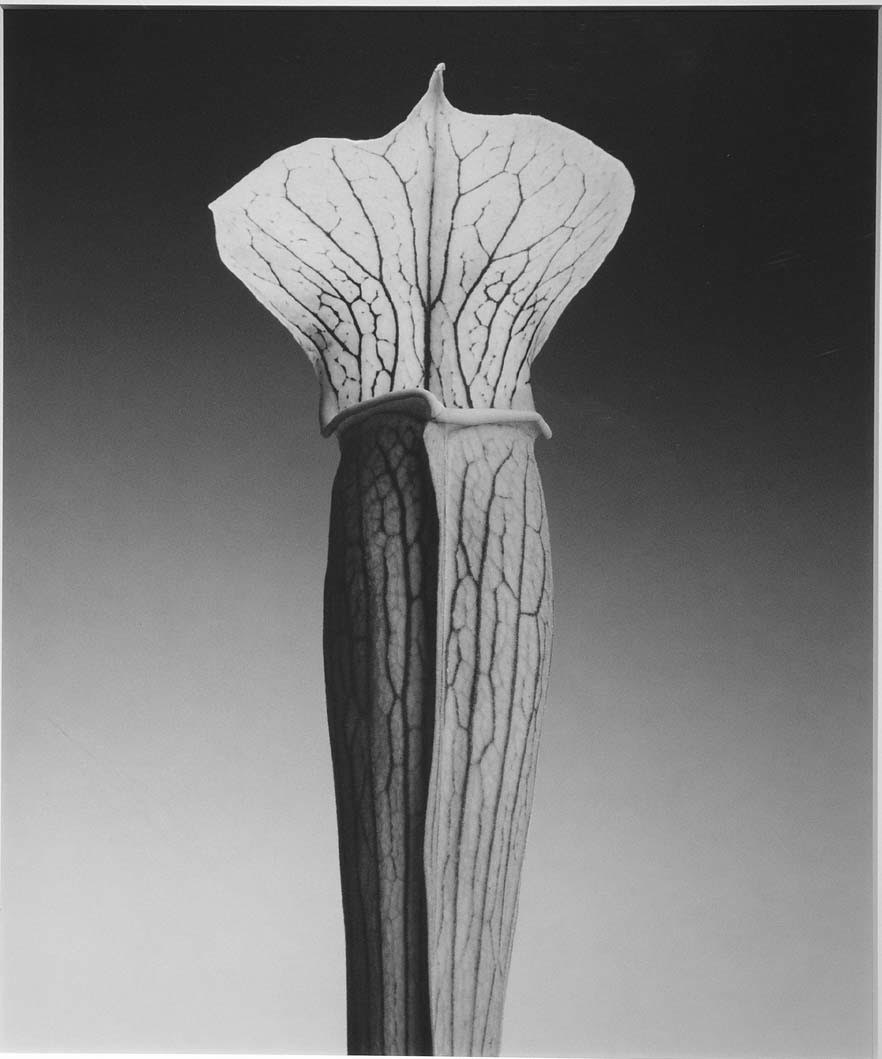

photo { Robert Mapplethorpe, Jack in the Pulpit, 1988 }

experience, olfaction | January 24th, 2019 5:08 pm

The tendency of people to forge friendships with people of a similar appearance has been noted since the time of Plato. But now there is research suggesting that, to a striking degree, we tend to pick friends who are genetically similar to us in ways that go beyond superficial features.

For example, you and your friends are likely to share certain genes associated with the sense of smell.

Our friends are as similar to us genetically as you’d expect fourth cousins to be, according to the study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. This means that the number of genetic markers shared by two friends is akin to what would be expected if they had the same great-great-great-grandparents. […]

The resemblance is slight, just about 1 percent of the genetic markers, but that has huge implications for evolutionary theory.

{ Washington Post | Continue reading }

polyvinyl chloride, colored with oil, mixed technique and accessories { Duane Hanson, Children Playing Game, 1979 }

genes, olfaction, relationships | April 25th, 2016 11:38 am

Most humans perceive a given odor similarly. But the genes for the molecular machinery that humans use to detect scents are about 30 percent different in any two people, says neuroscientist Noam Sobel. […] This variation means that nearly every person’s sense of smell is subtly different. [….]

Sobel and his colleagues designed a sensitive scent test they call the “olfactory fingerprint.” […] People with similar olfactory fingerprints showed similarity in their genes for immune system proteins linked to body odor and mate choice. […]

It has been shown that people can use smell to detect their genetic similarity to others and avoid inbreeding, says neuroscientist Joel Mainland of Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia.

{ Science News | Continue reading }

photo { Juergen Teller, Octopussy, Rome, 2008 }

genes, olfaction | June 23rd, 2015 2:04 pm

A fragrant object lies before you—say, a flower, some stinky cheese, or a smelly sock. Molecules break off from the object, evaporating into the air and floating towards your face. A sniff pulls the molecules into your nostril, where they travel through your nasal cavity towards your olfactory neurons, which extend out through holes in your skull into the mucus layer of your nose. The molecules activate receptors studding the outside layer of individual neurons, which send a message to your brain that something smells.

Humans have around 350 types of receptors on 40 million neurons, which in combination allow us to distinguish more than a trillion different odors. Despite this incredible power of olfaction, the human sense of smell is often neglected, considered a holdover from our animal past or a source of unseemly sensations. It doesn’t help that odors are often literally beneath us; the evolutionary argument goes that when early humans started walking upright, our nose got farther away from the smells on the ground, decreasing the relative importance of olfaction for getting around. Evidence contradicting this story came from a 2006 study which recruited undergraduate students to get on all fours and track the scent of chocolate oil dripped on grass. They were remarkably good at it, showing that our “bad” sense of smell isn’t biologically determined—it’s just that we’re out of practice. […]

We know a lot about how a smell signal travels from an activated receptor on a neuron to the brain. This pathway has been worked out in painstaking detail, with cascades of cellular switches and neural action potentials that signal our brain. […] But how does a smelly molecule activate its receptor in the first place? There is still no satisfactory answer to this question despite nearly a century of research.

{ The New Inquiry | Continue reading }

photo { Juno Calypso, Disenchanted Simulation, 2013 }

olfaction | February 16th, 2015 1:22 pm

Noise cancellation is a traditional problem in statistical signal processing that has not been studied in the olfactory domain for unwanted odors.

In this paper, we use the newly discovered olfactory white signal class to formulate optimal active odor cancellation using both nuclear norm-regularized multivariate regression and simultaneous sparsity or group lasso-regularized non-negative regression.

As an example, we show the proposed technique on real-world data to cancel the odor of durian, katsuobushi, sauerkraut, and onion.

{ IEEE Workshop on Statistical Signal Processing | PDF }

olfaction | July 25th, 2014 10:06 am

Human skin is inhabited and re-populated depending on health conditions, age, genetics, diet, the weather and climate zones, occupations, cosmetics, soaps, hygienic products and moisturizers. All these factors contribute to the variation in the types of microbes. Population of viruses, for example, can include a mixture of good ones - like bacteriophages fighting acne-causing Propionibacterium - and bad ones - as highly contagious Mesles. Bacterial communities include thousands of species of Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Cyanobacteria, Proteobacteria, and fungi Malassezia. […]

The major odor-causing substances are sulphanyl alkanols, steroid derivatives and short volatile branched-chain fatty acids.

Most common sulphanyl alkanol in human sweat, 3-methyl-3-sulfanylhexan-1-ol is produced by bacteria in several ways. […] Besides being a major descriptor of human sweat odor, is also present in beers.

{ Aurametrix | Continue reading }

olfaction, science | September 10th, 2013 12:16 pm

Sex pheromones are chemical compounds released by an animal that attract animals of the same species but opposite sex. They are often so specific that other species can’t smell them at all, which makes them useful as a secret communication line for just that species. But this specificity raises an intriguing question: When a new species evolves and uses a new pheromone signaling system, what comes first: the ability to make the pheromone or the ability to perceive it? […]

Any individuals that make a new and different scent would then be perceived by the receivers as being the wrong species and they won’t attract any mates. If you don’t attract mates, you can’t pass on your new genes for your new scent. This produces a strong pressure to make a scent that is as similar as the scent produced by everyone else as possible (this is called stabilizing selection). With this intense pressure to be like everyone else, how did the incredible diversity of species-specific pheromones come to be?

{ Nature | Continue reading }

animals, olfaction, science | August 7th, 2013 6:05 am

On a street in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, an unremarkable gray box protrudes from a telephone pole. Inside the box lies a state-of-the-art airflow-sampling device, one part of an experiment to track how a gas disperses through the city’s streets and subway system. […]

The goal of the project is to develop a model for how a dangerous airborne contaminant, such as sarin gas or anthrax, would spread throughout the city in the event of a terrorist attack or accidental release.

The scientists released tiny amounts of a colorless, nontoxic gas at several locations around the city. The airflow samplers, located at various points throughout the city, measured the gas to determine how fast and how far it spread.

{ LiveScience | Continue reading }

unrelated { Eproctophilia is a paraphilia in which people are sexually aroused by flatulence. The following account presents a brief case study of an eproctophile. | Improbable }

crime, olfaction, technology | July 27th, 2013 5:39 am

The sense of smell is one of our most powerful connections to the physical world. Our noses contain hundreds of different scent receptors that allow us to distinguish between odours. When you smell a rose or a pot of beef stew, the brain is responding to scent molecules that have wafted into your nose and locked on to these receptors. Only certain molecules fit specific receptors, and when they slot together, like a key in a lock, this triggers changes in cells. In the case of scent receptors, specialised neurons send messages to the brain so we know what we have sniffed. […]

In the last ten years, however, reports have trickled in from bemused biologists that these receptors, as well as similar ones usually found on taste buds, crop up all over our bodies.

{ BBC | Continue reading }

genes, olfaction | July 16th, 2013 1:57 pm

The objective of this study was to determine test characteristics (i.e., intra- and interobserver variability, intraassay variability, sensitivity, and specificity) of an evaluation of odor from vaginal discharge (VD) of cows in the first 10 days postpartum conducted by olfactory cognition and an electronic device, respectively. […]

The study revealed a considerable subjectivity of the human nose concerning the classification into healthy and sick animals based on the assessment of vaginal discharge.

{ Journal of Dairy Science }

animals, gross, olfaction, science | July 10th, 2013 9:26 am

Around 1 in 7,500 otherwise healthy people are born with no sense of smell, a condition known as isolated congenital anosmia (ICA). So dominant are sight and hearing to our lives, you might think this lack of smell would be fairly inconsequential. In fact, a study of individuals with ICA published last year showed just how important smell is to humans. Compared with controls, the people with ICA were more insecure in their relationships, more prone to depression and to household accidents.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

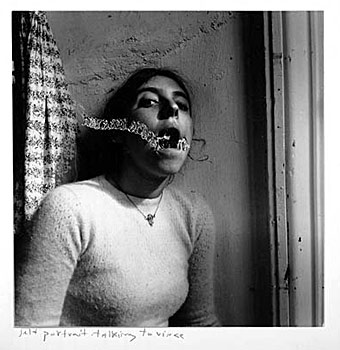

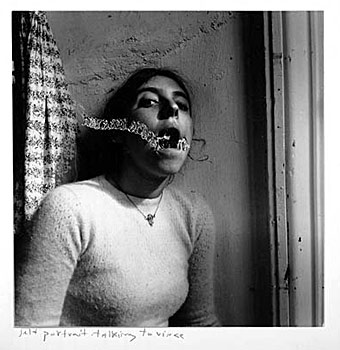

photo { Francesca Woodman, Self-portrait talking to Vince, Providence, RI (RISD), 1975-78 }

olfaction, relationships | April 4th, 2013 12:37 pm

Men who were born without a sense of smell report having far fewer sexual partners than other men do, and women with the same disorder report being more insecure in their partnerships, according to new research.

The researchers don’t know why romantic difficulties could be tied to smell, but they say one possibility is that people with anosmia, or no sense of smell, are insecure, having missed many emotional signals all their life.

{ LiveScience | Continue reading }

photos { Sarah Pickering, Fuel Air Explosion (L), Land Mine (R) }

olfaction, sex-oriented | January 28th, 2013 8:04 am

Explicit communication involves the deliberate, conscious choosing of words and signals to convey a specific message to a recipient or target audience. […] Much of human communication is also implicit, and occurs subconsciously without overt individual attention. Examples include nonverbal communication and subconscious facial expressions, which have been argued to contribute significantly to human communication and understanding. […] Additionally, recent studies conducted by evolutionary psychologists and biologists have revealed that other animals, including humans, may also communicate information implicitly via the production and detection of chemical olfactory cues. Of specific interest to evolutionary psychologists has been the investigation of human chemical cues indicating female reproductive status. These subliminally perceived chemical cues (odors) are often referred to as pheromones.

For two decades, psychologists studying ovulation have successfully employed a series of “T-shirt studies” supporting the hypothesis that men can detect when a woman is most fertile based on olfactory detection of ovulatory cues. However, it is not known whether the ability to detect female fertility is primarily a function of biological sex, sexual orientation, or a combination of both.

Using methodologies from previous T-shirt studies, we asked women not using hormonal contraceptives to wear a T-shirt for three consecutive nights during their follicular (ovulatory) and luteal (non-ovulatory) phases. Male and female participants of differing sexual orientations then rated the T-shirts based on intensity, pleasantness, and sexiness.

Heterosexual males were the only group to rate the follicular T-shirts as more pleasant and sexy than the luteal T-shirts. Near-significant trends also indicated that heterosexual men and non-heterosexual women consistently ranked the T-shirts, regardless of menstrual stage, to be more intense, pleasant, and sexy than did non-heterosexual men and heterosexual women.

{ Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology | PDF }

hormones, olfaction, relationships, sex-oriented | January 25th, 2013 8:44 am

Did you know that around 85% of humans only breathe out of one nostril at a time? This fact may surprise you, but even more remarkable is the following: our body follows a pattern and switches from breathing out of one nostril to the other in a cyclical way. Typically, every four hours it switches from left to right, or right to left.

{ United Academics | Continue reading }

images { John Stezaker, The Voyeur, 1979 | 2 }

halves-pairs, olfaction, science | January 17th, 2013 9:58 am

Pleasantness of an odor is attributed mainly to associative learning: The odor acquires the hedonic value of the (emotional) context in which the odor is first experienced. Associative learning demonstrably modifies the pleasantness of odors, particularly odors related to foods. Experimentally, classical conditioning paradigms (Pavlovian conditioning) have been shown to modify the responses to odors, not only in animals but also in humans (olfactory conditioning).

In olfactory conditioning an olfactory stimulus is the conditioned stimulus that has been paired with an unconditioned stimulus (e.g., taste). For instance, the pleasantness of odors with originally neutral hedonic value was improved after the odors were paired as few as three times with the pleasant unconditioned stimulus, sweet taste. This type of conditioning, where liking of a stimulus changes because the stimulus has been paired with another, positive or negative, stimulus is called evaluative conditioning.

Naturally occurring evaluative conditioning may be important also in modifying the pleasantness of a partner’s body odors (conditioned stimulus) that are encountered initially during affection and sexual intercourse (unconditioned stimulus), because the sexual experiences presumably provide strong, positive, emotional context.

Searches for human pheromones have focused on androstenes, androgen steroids occurring in apocrine secretions, for example, axillary (underarm) sweat, motivated by the fact that one of them, androstenone, functions as a sex pheromone in pigs. However, some 20–40% of adult humans, depending on age and sex, cannot smell androstenone, although their sense of smell is otherwise intact. To date, no convincing evidence exists to demonstrate that any single compound is able to function as a sexual attractant in humans, although several other types of pheromonal effects (e.g., kin recognition) have been observed.

While many studies have explored potential physiological and behavioral effects of the odors of androstenes, we asked a different question: Could an odor (conditioned stimulus) that is perceived during sexual intercourse gain hedonic value from the intercourse experience (presumably a pleasant unconditioned stimulus) through associative learning? While experimental challenges limit human studies of this kind, we approached the question by asking young adults, randomly sampled regarding the level of sexual experience and olfactory function, to rate the pleasantness of body-related (androstenone and isovaleric acid) and control odorants (chocolate, cinnamon, lemon, and turpentine). We compared the responses of participants with and without experience in sexual intercourse and hypothesized that those with intercourse experience would rate the pleasantness of the odor of androstenone higher than would those without such experience. […]

The results suggest that, among women, sexual experience may modify the pleasantness of the odor of androstenone.

{ Archives of Sexual Behavior/Springer | Continue reading }

olfaction, relationships, sex-oriented | December 7th, 2012 3:00 pm

The study, reported in The Journal of Neuroscience [2007], provides the first direct evidence that humans, like rats, moths and butterflies, secrete a scent that affects the physiology of the opposite sex. (…)

He found that the chemical androstadienone — a compound found in male sweat and an additive in perfumes and colognes — changed mood, sexual arousal, physiological arousal and brain activation in women.

Yet, contrary to perfume company advertisements, there is no hard evidence that humans respond to the smell of androstadienone or any other chemical in a subliminal or instinctual way similar to the way many mammals and even insects respond to pheromones, Wyart said. Though some humans exhibit a small patch inside their nose resembling the vomeronasal organ in rats that detects pheromones, it appears to be vestigial, with no nerve connection to the brain.

“Many people argue that human pheromones don’t exist, because humans don’t exhibit stereotyped behavior. Nonetheless, this male chemical signal, androstadienone, does cause hormonal as well as physiological and psychological changes in women.” (…)

Sweat has been the main focus of research on human pheromones, and in fact, male underarm sweat has been shown to improve women’s moods and affect their secretion of luteinizing hormone, which is normally involved in stimulating ovulation.

Other studies have shown that when female sweat is applied to the upper lip of other women, these women respond by shifting their menstrual cycles toward synchrony with the cycle of the woman from whom the sweat was obtained.

{ ScienceDaily | Continue reading }

archives, hormones, olfaction, relationships | April 9th, 2012 2:12 pm