theory

I understand by ‘God’ the perfect being, where a being is perfect just in case it has all perfections essentially and lacks all imperfections essentially. […]

Given that there are good reasons for thinking that the premises of the Compossibility Argument (CA) are true, it seems to me we have a good reason to think that God’s existence is possible. Of course, this does not, by itself, allow us to conclude to the much more important thesis that God exists, and so the atheist can consistently admit God’s possibility and maintain her atheism.

{ C’Zar Bernstein/Academia | Continue reading }

The omnipotence paradox states that: If a being can perform any action, then it should be able to create a task which this being is unable to perform; hence, this being cannot perform all actions. Yet, on the other hand, if this being cannot create a task that it is unable to perform, then there exists something it cannot do.

One version of the omnipotence paradox is the so-called paradox of the stone: “Could an omnipotent being create a stone so heavy that even he could not lift it?” If he could lift the rock, then it seems that the being would not have been omnipotent to begin with in that he would have been incapable of creating a heavy enough stone; if he could not lift the stone, then it seems that the being either would never have been omnipotent to begin with or would have ceased to be omnipotent upon his creation of the stone.

The argument is medieval, dating at least to the 12th century, addressed by Averroës (1126–1198) and later by Thomas Aquinas. Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (before 532) has a predecessor version of the paradox, asking whether it is possible for God to “deny himself”.

[…]

A common response from Christian philosophers, such as Norman Geisler or Richard Swinburne is that the paradox assumes a wrong definition of omnipotence. Omnipotence, they say, does not mean that God can do anything at all but, rather, that he can do anything that’s possible according to his nature.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

related { Jesus and Virgin Mary spotted on Google Earth pic }

theory | June 2nd, 2014 11:51 am

The arguments for ditching notes and coins are numerous, and quite convincing. In the US, a study by Tufts University concluded that the cost of using cash amounts to around $200 billion per year – about $637 per person. This is primarily the costs associated with collecting, sorting and transporting all that money, but also includes trivial expenses like ATM fees. Incidentally, the study also found that the average American wastes five and a half hours per year withdrawing cash from ATMs; just one of the many inconvenient aspects of hard currency.

While coins last decades, or even centuries, paper currency is much less durable. A dollar bill has an average lifespan of six years, and the US Federal Reserve shreds somewhere in the region of 7,000 tons of defunct banknotes each year.

Physical currency is grossly unhealthy too. Researchers in Ohio spot-checked cash used in a supermarket and found 87% contained harmful bacteria. Only 6% of the bills were deemed “relatively clean.” […]

Stockholm’s homeless population recently began accepting card payments. […]

Cash transactions worldwide rose just 1.75% between 2008 and 2012, to $11.6 trillion. Meanwhile, non traditional payment methods rose almost 14% to total $6.4 trillion.

{ TransferWise | Continue reading }

The anal stage is the second stage in Sigmund Freud’s theory of psychosexual development, lasting from age 18 months to three years. According to Freud, the anus is the primary erogenous zone and pleasure is derived from controlling bladder and bowel movement. […]

The negative reactions from their parents, such as early or harsh toilet training, can lead the child to become an anal-retentive personality. If the parents tried forcing the child to learn to control their bowel movements, the child may react by deliberately holding back in rebellion. They will form into an adult who hates mess, is obsessively tidy, punctual, and respectful to authority. These adults can sometimes be stubborn and be very careful over their money.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

related { Hackers Hit Mt. Gox Exchange’s CEO, Claim To Publish Evidence Of Fraud | Where are the 750k Bitcoins lost by Mt. Gox? }

economics, psychology, theory | March 10th, 2014 8:28 am

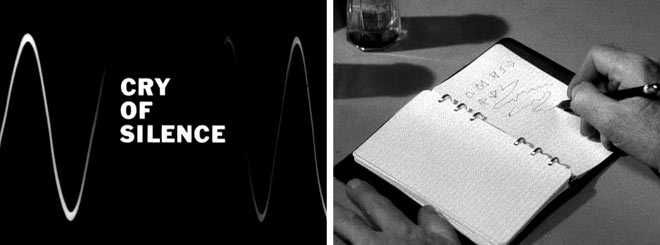

Quantum physics is famously weird, counterintuitive and hard to understand; there’s just no getting around this. So it is very reassuring that many of the greatest physicists and mathematicians have also struggled with the subject. The legendary quantum physicist Richard Feynman famously said that if someone tells you that they understand quantum mechanics, then you can be sure that they are lying. And Conway too says that he didn’t understand the quantum physics lectures he took during his undergraduate degree at Cambridge.

The key to this confusion is that quantum physics is fundamentally different to any of the previous theories explaining how the physical world works. In the great rush of discoveries of new quantum theory in the 1920s, the most surprising was that quantum physics would never be able to exactly predict what was going to happen. In all previous physical theories, such as Newton’s classical mechanics or Einstein’s theories of special and general relativity, if you knew the current state of the physical system accurately enough, you could predict what would happen next. “Newtonian gravitation has this property,” says Conway. “If I take a ball and I throw it vertically upwards, and I know its mass and I know its velocity (suppose I’m a very good judge of speed!) then from Newton’s theories I know exactly how high it will go. And if it doesn’t do exactly as I expect then that’s because of some slight inaccuracy in my measurements.”

Instead quantum physics only offers probabilistic predictions: it can tell you that your quantum particle will behave in one way with a particular probability, but it could also behave in another way with another particular probability. “Suppose there’s this little particle and you’re going to put it in a magnetic field and it’s going to come out at A or come out at B,” says Conway, imagining an experiment, such as the Stern Gerlach experiment, where a magnetic field diverts an electron’s path. “Even if you knew exactly where the particles were and what the magnetic fields were and so on, you could only predict the probabilities. A particle could go along path A or path B, with perhaps 2/3 probability it will arrive at A and 1/3 at B. And if you don’t believe me then you could repeat the experiment 1000 times and you’ll find that 669 times, say, it will be at A and 331 times it will be at B.”

{ The Free Will Theorem, Part I | Continue reading | Part II | Part III }

Physics, theory | March 4th, 2014 4:26 pm

The key way that economists model behavior is by assuming that people have preferences about things. Often, but not always, these preferences are expressed in the form of a utility function. But there are some things that could happen that could seriously mess with this model. Most frightening are “framing effects”. This is when what you want depends on how it’s presented to you. […]

One of the most important tools we have to describe people’s behavior over time is the notion of time preference, also called “discounting”. This means that we assume that people care about the future less than they care about the present. Makes sense, right? But while certain kinds of discounting cause people’s choices to be inconsistent, other kinds would cause people to make inconsistent decisions. For example, some people might choose not to study hard in college, even though they realize that someday they’ll wake up and say “Man, if I could go back in time I would have studied more in college!”. This kind of thing is called hyperbolic discounting. It would make it a lot harder to model human behavior. But the models would still be possible to make.

But what would be really bad news is if people’s time preferences switched depending on framing effects! If that happened, then it would be very, very hard to model individual decision-making over time.

Unfortunately, that is exactly what experimental economist David Eil of George Mason University has found in a new experiment.

{ Noahpinion | Continue reading }

economics, psychology, theory | January 31st, 2014 1:50 pm

Since 1955, The Journal of Irreproducible Results has offered “spoofs, parodies, whimsies, burlesques, lampoons and satires” about life in the laboratory. Among its greatest hits: “Acoustic Oscillations in Jell-O, With and Without Fruit, Subjected to Varying Levels of Stress” and “Utilizing Infinite Loops to Compute an Approximate Value of Infinity.” The good-natured jibes are a backhanded celebration of science. What really goes on in the lab is, by implication, of a loftier, more serious nature.

It has been jarring to learn in recent years that a reproducible result may actually be the rarest of birds. Replication, the ability of another lab to reproduce a finding, is the gold standard of science, reassurance that you have discovered something true. But that is getting harder all the time. With the most accessible truths already discovered, what remains are often subtle effects, some so delicate that they can be conjured up only under ideal circumstances, using highly specialized techniques.

Fears that this is resulting in some questionable findings began to emerge in 2005, when Dr. John P. A. Ioannidis, a kind of meta-scientist who researches research, wrote a paper pointedly titled “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False.”

[…]

The fear that much published research is tainted has led to proposals to make replication easier by providing more detailed documentation, including videos of difficult procedures. […] Scientists talk about “tacit knowledge,” the years of mastery it can take to perform a technique. The image they convey is of an experiment as unique as a Rembrandt.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

science, theory, uh oh | January 25th, 2014 7:55 am

What if the universe had no beginning, and time stretched back infinitely without a big bang to start things off? That’s one possible consequence of an idea called “rainbow gravity,” so-named because it posits that gravity’s effects on spacetime are felt differently by different wavelengths of light, aka different colors in the rainbow. […]

“It’s a model that I do not believe has anything to do with reality,” says Sabine Hossenfelder of the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

Physics, theory | December 10th, 2013 3:27 pm

For a couple years now I’ve been fascinated by some recent ideas about how complexity evolves. Darwin’s great insight was recognizing how natural selection could create complex traits. All that was needed was a series of intermediates that raised the reproductive success of organisms. But recently some researchers have developed ideas in which natural selection doesn’t play such a central role.

One idea, laid out in the book Biology’s First Law, holds that life has a built-in propensity to get more complex–even in the absence of natural selection. According to another idea, called constructive neutral evolution, mutations can change simple structures into more complex ones even if those mutations don’t provide an advantage. The scientists who are championing these ideas don’t see them as refuting natural selection, but, rather, complementing it, and enriching our understanding of how evolution works.

{ Carl Zimmer | Continue reading | More: Scientists are exploring how organisms can evolve elaborate structures without Darwinian selection }

science, theory | July 17th, 2013 9:20 am

Big news from the annals of science last week. A British newspaper reports that the mysteries of the universe may have been solved by a hedge-fund economist who left academia 20 years ago. Eric Weinstein’s theory – he calls it geometric unity – posits a 14-dimensional “observerse”, which contains our work-a-day, four-dimensional, space-time universe.

{ The National | Continue reading | More: Guardian }

photo { Alessandra Celauro }

photogs, theory | May 30th, 2013 12:29 pm

Modern physics deals with some ridiculously non-intuitive stuff. Objects act as though they gain mass the faster they move. An electron can’t decide if it’s a particle, a wave or both. However, there is one statement that takes the cake on sounding like crazy talk: Empty space isn’t empty.

If you take a container, pump all the air out of it, shield it from electric fields and plop it in the deepest of intergalactic space to get it away from gravitational fields, that container should contain absolutely nothing. However, that’s not what happens.

At the quantum scale, space is a writhing, frantic, ever-changing foam, with particles popping into existence and disappearing in the wink of an eye. This is not just a theoretical idea—it’s confirmed. How can this bizarre idea be true?

Even though in classical physics we are taught that energy is conserved, which means it cannot change, one of the tenets of quantum mechanics says that energy doesn’t have to be conserved if the change happens for a short enough time. So even if space had zero energy, it would be perfectly OK for a little energy to pop into existence for a tiny split second and then disappear—and that’s what happens in empty space. And since energy and matter are the same (thank Einstein for teaching us that E=mc2 thing), matter can also appear and disappear.

And this appears everywhere. At the quantum level, matter and antimatter particles are constantly popping into existence and popping back out, with an electron-positron pair here and a top quark-antiquark pair there. This behavior is the reason that scientists call these ephemeral particles “quantum foam”: It’s similar to how bubbles in foam form and then pop.

{ Fermilab | Continue reading }

photo { Robert Adams }

photogs, science, theory | February 2nd, 2013 6:26 am

String theory is an attempt to describe all particles and all forces in nature in one unified theoretical framework. It encompasses quantum mechanics and gravity, and it is based on the idea that the fundamental building blocks of matter are not particles, but strings: objects which have some length, and which can vibrate in different ways.

{ Steven Gubser on String Theory | Continue reading }

images { 1 | 2 }

science, theory | January 18th, 2013 9:36 am

Perhaps no other human trait is as variable as human height. […] The source of that variation is something that anthropologists have been trying to root out for decades. Diet, climate and environment are frequently linked to height differences across human populations.

More recently, researchers have implicated another factor: mortality rate. In a new study in the journal Current Anthropology, Andrea Bamberg Migliano and Myrtille Guillon, both of the University College London, make the case that people living in populations with low life expectancies don’t grow as tall as people living in groups with longer life spans.

{ Smithsonian | Continue reading }

science, theory | December 27th, 2012 3:22 pm

Implicit in the rationalist literature on bargaining over the last half-century is the political utility of violence. Given our anarchical international system populated with egoistic actors, violence is thought to promote concessions by lending credibility to their threats. In dyadic competitions between a defender and challenger, violence enhances the credibility of his threat via two broad mechanisms familiar to theorists of international relations. First, violence imposes costs on the challenger, credibly signaling resolve to fight for his given preferences. Second, violence imposes costs on the defender, credibly signaling pain to him for noncompliance (Schelling 1960, 1966). All else equal, this forceful demonstration of commitment and punishment capacity is believed to increase the odds of coercing the defender’s preferences to overlap with those of the challenger in the interest of peace, thereby opening up a proverbial bargaining space. Such logic is applied in a wide range of contexts to explain the strategic calculus of states, and increasingly, non-state actors.

From the vantage of bargaining theory, then, empirical research on terrorism poses a puzzle. For non-state challengers, terrorism does in fact signal a credible threat in comparison to less extreme tactical alternatives. In recent years, however, a spate of empirical studies across disciplines and methodologies has nonetheless found that neither escalating to terrorism nor with terrorism encourages government concessions. In fact, perpetrating terrorist acts reportedly lowers the likelihood of government compliance, particularly as the civilian casualties rise. The apparent tendency for this extreme form of violence to impede concessions challenges the external validity of bargaining theory, as traditionally understood. In Kuhnian terms, the negative coercive value from escalating represents a newly emergent anomaly to the reigning paradigm, inviting reassessment of it (Kuhn 1962).

That is the purpose of this study.

{ International Studies Quarterly | PDF }

related { Making China’s nuclear war plan | PDF }

fights, ideas, theory | October 19th, 2012 12:55 pm

When humans evolved bigger brains, we became the smartest animal alive and were able to colonise the entire planet. But for our minds to expand, a new theory goes, our cells had to become less willing to commit suicide – and that may have made us more prone to cancer.

When cells become damaged or just aren’t needed, they self-destruct in a process called apoptosis. In developing organisms, apoptosis is just as important as cell growth for generating organs and appendages – it helps “prune” structures to their final form.

By getting rid of malfunctioning cells, apoptosis also prevents cells from growing into tumours. […]

McDonald suggests that humans’ reduced capacity for apoptosis could help explain why our brains are so much bigger, relative to body size, than those of chimpanzees and other animals. When a baby animal starts developing, it quickly grows a great many neurons, and then trims some of them back. Beyond a certain point, no new brain cells are created.

Human fetuses may prune less than other animals, allowing their brains to swell.

{ NewScientist | Continue reading }

brain, health, science, theory | October 15th, 2012 11:53 am

Two traits that set humans apart from other primates—big brains and the ability to walk upright—could be at odds when it comes to childbirth. Big brains and the big heads that encase them are hard to push through the human birth canal, but a wider pelvis might compromise bipedal walking. Scientists have long posited that nature’s solution to this problem, which is known as the “obstetric dilemma,” was to shorten the duration of gestation so that babies are born before their heads get too big. As a result, human babies are relatively helpless and seemingly underdeveloped in terms of motor and cognitive ability compared to other primates.

“All these fascinating phenomena in human evolution—bipedalism, difficult childbirth, wide female hips, big brains, relatively helpless babies—have traditionally been tied together with the obstetric dilemma,” said Holly Dunsworth, an anthropologist at the University of Rhode Island and lead author of the research. “It’s been taught in anthropology courses for decades, but when I looked for hard evidence that it’s actually true, I struck out.” The first problem with the theory is that there is no evidence that hips wide enough to deliver a more developed baby would be a detriment to walking, Dunsworth said. Anna Warrener, a post-doctoral researcher at Harvard University and one of the paper’s co-authors, has studied how hip breadth affects locomotion with women on treadmills. She found that there is no correlation between wider hips and a diminished locomotor economy.

Then Dunsworth looked for evidence that human pregnancy is shortened compared to other primates and mammals. She found well-established research to the contrary. “Controlling for mother’s body size, human gestation is a bit longer than expected compared to other primates, not shorter,” she said. “And babies are a bit larger than expected, not smaller. Although babies behave like it, they’re not born early.”

For mammals in general, including humans, gestation length and offspring size are predicted by mother’s body size. Because body size is a good proxy for an animal’s metabolic rate and function, Dunsworth started to wonder if metabolism might offer a better explanation for the timing of human birth than the pelvis.

{ Medical Xpress | Continue reading }

photo { Steve McCurry }

kids, science, theory | August 28th, 2012 9:00 am

One of the worst parts of being pregnant […] is what is commonly referred to as morning sickness.

This term for the nausea and vomiting accompanying pregnancy is something of a misnomer, actually, since such gastrointestinal issues certainly aren’t limited to the morning hours. Rather, for those women who do get green around the gills (and not all do; more on that later) sudden bouts of toilet-hugging can happen morning, noon and night. […]

Why, if it is indeed an evolutionary adaptation, does pregnancy sickness not occur in all (or at least, almost all) pregnant women? […]

So what does Gallup say is the real culprit behind nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy? Semen. More specifically, unfamiliar semen.

Gallup’s evolutionary reinterpretation of pregnancy sickness is quite new—so new, in fact, that it hasn’t been put to a test. But at the 2012 meeting of the Northeastern Evolutionary Psychology Society in Plymouth, N.H., he and graduate student Jeremy Atkinson laid out a set of explicit predictions that, if borne out by data, would support their model and may lead scholarship away from the traditional embryo-protection account.

First, the authors predict that the intensity of pregnancy sickness should be directly proportional to the frequency of insemination by the child’s father. “Risk factors for morning sickness,” they reason, “should include condom use, infrequent insemination, and not being in a committed relationship.” In fact, Gallup and Atkinson believe that lesbians with little (if any) previous exposure to semen who are impregnated by artificial insemination should have some of the worst cases of nausea and vomiting. Also, pregnancy sickness should wane in severity from one consecutive pregnancy to the next, but only assuming that the same man sires each successive offspring. By contrast, a change in paternity between offspring should reinstate pregnancy sickness.

{ Slate | Continue reading }

health, kids, science, sex-oriented, theory | July 11th, 2012 12:57 pm

Could mirror universes or parallel worlds account for dark matter — the ‘missing’ matter in the Universe? In what seems to be mixing of science and science fiction, a new paper by a team of theoretical physicists hypothesizes the existence of mirror particles as a possible candidate for dark matter. An anomaly observed in the behavior of ordinary particles that appear to oscillate in and out of existence could be from a “hypothetical parallel world consisting of mirror particles,” says a press release from Springer. “Each neutron would have the ability to transition into its invisible mirror twin, and back, oscillating from one world to the other.”

{ Universe Today | Continue reading }

photo { Aaron Fowler }

mystery and paranormal, photogs, space, theory | June 20th, 2012 6:32 am

Women are picky. The general idea is that females invest more in reproduction, and, as such, need to be more selective about their partners. This purportedly has its root in anisogamy, a complicated word to say that egg cells are more expensive to produce, and lesser in number, than sperm cells. Basically, females have to use their egg cells carefully, while men can go around and generously spread their sperm. […]

Two main suggestions:

• Sexy sons: choosy females pick sexy males to mate with. Their offspring inherits both the preference and the attractiveness. And a positive feedback loop follows.

• Good genes: male attractiveness signals additional quality, or more precisely breeding value for fitness. The sons of attractive males inherit these qualities along with the ‘being sexy.’ Here, there is a link between attractiveness and ‘quality.’

{ The Beast, the bard and the bot | Continue reading }

images { 1. Phillip Pearstein | 2 }

relationships, science, theory | May 16th, 2012 12:14 pm

The great innovations come with side-effects. I have encountered people who said this about our chronic back pains being a side-effect of upright walking. It is a great thing but may have a couple of weak spots. We would actually be surprised if evolution didn’t take some time in a shake down of a new species.

A recent paper in Cell by 20 authors has tackled the question of whether autism is the unfortunate result of the malfunctioning of a relatively new aspect of the human brain.

{ Thoughts on thoughts | Continue reading }

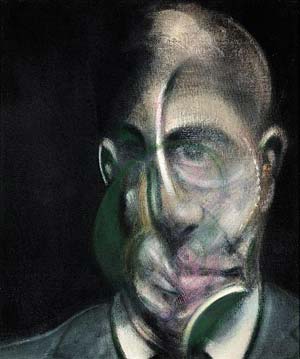

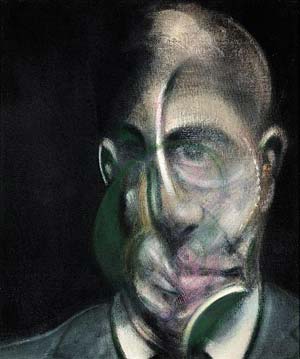

painting { Francis Bacon, Portrait of Michel Leiris, 1976 }

Francis Bacon, brain, theory | May 15th, 2012 5:39 am

The parent-offspring conflict theory delineates a zone of conflict between the mother and her offspring over weaning. We expect that the mother would try to wean her offspring off a little earlier than the offspring would be ready to wean themselves, thereby entering the zone of conflict for a short span of time. Though the theory was originally formulated in the context of weaning, it is also relevant in other contexts where a parent and his/her offspring have conflicting interests. Conflict has been reported over feeding, grooming, traveling, evening nesting, and mating in various species.

There are several theoretical models that address parent-offspring conflict in different contexts like reproduction, intra-brood competition, sexual conflict, and parental favoritism toward particular offspring. Though relatedness between parents, offspring and siblings can be measured easily, it is not easy to measure precisely parental investment and the costs and benefits to the concerned parties in nature. In some studies attempts have been made to quantify parental care in terms of milk ingested by offspring, sometimes as a correlate of weight gain by the individual pups, and sometimes by the duration of suckling. However, we have to accept that there is considerable variation in the suckling rates of individual pups, and in hunger levels of individuals, and hence such measures can only provide a rough estimate of parental investment. It is therefore not surprising that empirical tests of the theory in a field set up are sparse, especially in the original context of weaning. The parent-offspring conflict theory has in fact been claimed to be one of the most contentious subjects in behavioral and evolutionary ecology and also one of the most recalcitrant to experimental investigation.

{ arXiv | PDF }

animals, science, theory | May 13th, 2012 3:55 pm

For decades, a small group of scientific dissenters has been trying to shoot holes in the prevailing science of climate change, offering one reason after another why the outlook simply must be wrong.

Over time, nearly every one of their arguments has been knocked down by accumulating evidence, and polls say 97 percent of working climate scientists now see global warming as a serious risk.

Yet in recent years, the climate change skeptics have seized on one last argument that cannot be so readily dismissed. Their theory is that clouds will save us.

They acknowledge that the human release of greenhouse gases will cause the planet to warm. But they assert that clouds — which can either warm or cool the earth, depending on the type and location — will shift in such a way as to counter much of the expected temperature rise and preserve the equable climate on which civilization depends.

Their theory exploits the greatest remaining mystery in climate science, the difficulty that researchers have had in predicting how clouds will change. The scientific majority believes that clouds will most likely have a neutral effect or will even amplify the warming, perhaps strongly, but the lack of unambiguous proof has left room for dissent.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

photo { Robert Whitman }

climate, theory | May 1st, 2012 8:59 am