psychology

Common parlance such as “ray of hope” depicts an association between hope and the perception of brightness. Building on research in embodied cognition and conceptual metaphor, we examined whether incidental emotion of hopelessness can affect brightness perception, which may influence people’s preference for lighting. Across four studies, we found that people who feel hopeless judge the environment to be darker (Study 1). As a consequence, hopeless people expressed a greater desire for ambient brightness and higher wattage light bulbs (Studies 2 and 3). Study 4 showed the reversal of the effect — being in a dimmer (vs. brighter) room induces greater hopelessness toward the perceived job search prospects. Taken together, these results suggest that hopeless feeling seems to bias people’s perceptual judgment of ambient brightness, which may potentially impact their electricity consumption.

{ SAGE }

psychology | August 7th, 2014 9:46 am

Using data from an online hotel reservation site, the authors jointly examine consumers’ quality choice decision at the time of purchase and subsequent satisfaction with the hotel stay.

They identify three circumstantial variables at the time of purchase that are likely to influence both the choice decisions and the postpurchase satisfaction: the time gap between purchase and consumption, distance between purchase and consumption, and time of purchase (business/nonbusiness hours).

The authors incorporate these three circumstantial variables into a formal two-stage economic model and find that consumers who travel farther and make reservations during business hours are more likely to select higher-quality hotels but are less satisfied.

{ JAMA | Continue reading }

photo { Philip Lorca-diCorcia, Roy, ‘in his 20s’, Los Angeles, California, $50 (Hustlers series), 1990-1992 }

photogs, psychology, transportation | August 7th, 2014 9:17 am

Everybody knows that men are women have some biological differences – different sizes of brains and different hormones. It wouldn’t be too surprising if there were some neurological differences too. The thing is, we also know that we treat men and women differently from the moment they’re born, in almost all areas of life. Brains respond to the demands we make of them, and men and women have different demands placed on them. […]

They report finding significant differences between the sexes, but don’t show the statistics that allow the reader to evaluate the size of any sex difference against other factors such as age or individual variability. […] A significant sex difference could be tiny compared to the differences between people of different ages, or compared to the normal differences between individuals.

{ The Conversation | Continue reading }

The most important thing to take from this research is – as the authors report – increasing gender equality disproportionately benefits women. This is because – no surprise! – gender inequality disproportionately disadvantages women. […] But the provocative suggestion of this study is that as societies develop we won’t necessarily see all gender differences go away. Some cognitive differences may actually increase when women are at less of a disadvantage.

{ Mind Hacks | Continue reading }

genders, neurosciences, psychology | July 30th, 2014 2:46 pm

What you order may have less to do with what you want and more to do with a menu’s layout and descriptions.

After analyzing 217 menus and the selections of over 300 diners, a Cornell study published this month showed that when it comes to what you order for dinner, two things matter most: what you see on the menu and how you imagine it will taste.

{ Cornell | Continue reading }

economics, food, drinks, restaurants, psychology | July 29th, 2014 9:51 am

Connecting with others increases happiness, but strangers in close proximity routinely ignore each other. Why? Two reasons seem likely: Either solitude is a more positive experience than interacting with strangers, or people misunderstand the consequences of distant social connections. […]

Prior research suggests that acting extroverted—that is, acting bold, assertive, energetic, active, adventurous, and talkative (the exact list has varied by study)—in laboratory experiments involving group tasks like solving jigsaw puzzles and planning a day together, generally leads to greater positive affect than acting introverted—lethargic, passive, and quiet—in those same situations. […]

Connecting with a stranger is positive even when it is inconsistent with the prevailing social norm. […]

Our experiments tested interactions that lasted anywhere from a few minutes to as long as 40 minutes, but they did not require repeated interactions or particularly long interactions with the same random stranger. Nobody in the connection condition, for instance, spent the weekend with a stranger on a train. Indeed, some research suggests that liking for a stranger may peak at a relatively short interaction, and then decline over time as more is learned about another person.

If, however, the amount of time spent in conversation with a distant stranger is inversely related to its pleasantness at some point along the time spectrum, then this only makes the results of our experiments even more surprising. On trains, busses, and waiting rooms, the duration of the conversation is relatively limited. These could be the kinds of brief “social snacks” with distant others that are maximally pleasant, and yet people still routinely avoid them.

{ Journal of Experimental Psychology: General | PDF | More: These Psychologists Think We’d Be Happier If We Talked to Strangers More }

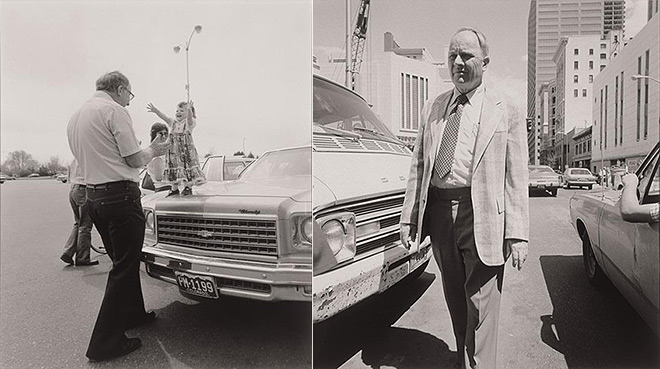

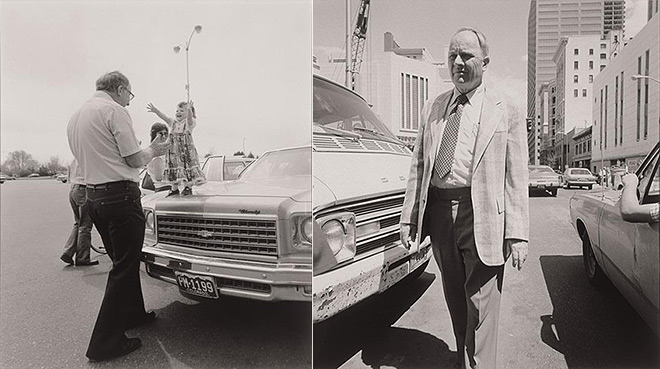

photos { Robert Adams, Our Lives and Our Children, 1981 }

psychology, relationships | July 21st, 2014 7:19 am

Major theories propose that spontaneous responding to others’ actions involves mirroring, or direct matching.

Responding to facial expressions is assumed to follow this matching principle: People smile to smiles and frown to frowns.

We demonstrate here that social power fundamentally changes spontaneous facial mimicry of emotional expressions, thereby challenging the direct-matching principle.

{ Journal of Experimental Psychology: General | PDF }

faces, psychology | July 21st, 2014 6:54 am

In general, we can detect a lie only about 54% of the time. […] We may not be very good detectors of lies, but as a species we are incredibly good at lying. […]

The more intelligent an animal is, the more likely it is to lie, which puts us humans right at the top of the ladder. Research has also shown that the best liars are also the best at detecting lies. […]

Given our increasing intelligence and the fairly basic methods used in lie detection, it seems unlikely that we’ll produce lie detectors that can pass muster in the near future. We have yet to fully understand the underlying psychological processes of lying so asking a machine to code it is ambitious, to say the least.

{ The Conversation | Continue reading }

images { Tilman Zitzmann | 2 }

psychology | July 17th, 2014 1:41 pm

An extensive literature addresses citizen ignorance, but very little research focuses on misperceptions. Can these false or unsubstantiated beliefs about politics be corrected? […] Results indicate that corrections frequently fail to reduce misperceptions among the targeted ideological group. We also document several instances of a ‘‘backfire effect’’ in which corrections actually increase misperceptions among the group in question.

{ Springer Science+Business Media | PDF }

ideas, psychology | July 16th, 2014 2:22 pm

Study: A 3 Second Interruption Doubles Your Odds of Messing Up

It’s called “contextual jitter” — in the time it takes to silence your cell phone, you’ve already lost track of what you were doing.

When their attention was shifted from the task at hand for a mere 2.8 seconds, they became twice as likely to mess up the sequence. The error rate tripled when the interruptions averaged 4.4 seconds.

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

psychology | July 15th, 2014 12:09 pm

Recent experimental studies show that emotions can have a significant effect on the way we think, decide, and solve problems. This paper presents a series of four experiments on how emotions affect logical reasoning.

In two experiments different groups of participants first had to pass a manipulated intelligence test. Their emotional state was altered by giving them feedback, that they performed excellent, poor or on average. Then they completed a set of logical inference problems (with if p, then q statements) either in a Wason selection task paradigm or problems from the logical propositional calculus.

Problem content also had either a positive, negative or neutral emotional value. Results showed a clear effect of emotions on reasoning performance. Participants in negative mood performed worse than participants in positive mood, but both groups were outperformed by the neutral mood reasoners.

Problem content also had an effect on reasoning performance. In a second set of experiments, participants with exam or spider phobia solved logical problems with contents that were related to their anxiety disorder (spiders or exams). Spider phobic participants’ performance was lowered by the spider-content, while exam anxious participants were not affected by the exam-related problem content.

Overall, unlike some previous studies, no evidence was found that performance is improved when emotion and content are congruent. These results have consequences for cognitive reasoning research and also for cognitively oriented psychotherapy and the treatment of disorders like depression and anxiety.

{ Frontiers | Continue reading }

photo { Ester Grass Vergara }

psychology | July 15th, 2014 11:00 am

Trivers (1976) introduced his theory of self-deception over three decades ago. According to his theory, individuals deceive themselves to better deceive others by placing truthful information in the unconscious while consciously presenting false information to others as well as the self without leaving cues to be detected of deception. […]

Humans and other primates live in hierarchical social groups where status influences resource distribution. High-status individuals who attained their position either by force or social intelligence have more resources than low-status individuals and have the power to punish the latter for rule violations. Low-status individuals who are under constant surveillance often attempt to hide resources from high-status individuals. In this case, low-status individuals should be more motivated to deceive, whereas high-status individuals should be more motivated to detect deception. High-status individuals have more honest means (through force or by changing the rules) to acquire resources than do low-status individuals. High-status individuals also have more resources—including information leading to the deception detection—and the means to punish deceivers. In contrast, low-status individuals are more limited detectors who may face revenge for detecting deception. Detecting deception does not enhance fitness if the detector is unable to punish but may be retaliated by the deceiver. There is thus more pressure to perfect deception when one has the need to deceive but also faces increased chances to be caught and punished. The same pressure to better deceive is much reduced when one expects little punishment from the detector if caught deceiving or has other honest means to pursue the same fitness gains. Social status may therefore shift selection pressure to favor low-status individuals over high-status individuals as fearful deceivers and the high-status individuals over low-status individuals as vigilant detectors. Thus, Trivers’ arms race between deception and detection is likely to have played out between low-status deceivers and high-status detectors, leading to people deceiving themselves to better deceive high- rather than low- or equal-status others. […]

According to Trivers (2000), a blatant deceiver keeps both true and false information in the conscious mind but presents only falsehoods to others. In doing so, the deceiver may leave clues about the truth due to its conscious access. A self-deceiver keeps only false information in consciousness. Lying to others and to the self at the same time, the self-deceiver thus leaves no clues about the truth retained in the unconscious mind. […]

Memory and its distortion may be temporarily employed first to keep truthful information away from both self and others and later to retrieve accurate information to benefit the self. Using a dual-retrieval paradigm, we tested the hypothesis that people are likely to deceive themselves to better deceive high- rather than equal-status others.

College student participants were explicitly instructed (Study 1 and 2) or induced (Study 3) to deceive either a high-status teacher or an equal-status fellow student. When interacting with the high- but not equal-status target, participants in three studies genuinely remembered fewer previously studied items than they did on a second memory test alone without the deceiving target.

The results support the view that self-deception responds to status hierarchy that registers probabilities of deception detection such that people are more likely to self-deceive high- rather than equal-status others.

{ Evolution Psychology | PDF }

art { Eric Yahnker }

psychology, relationships | July 11th, 2014 1:01 pm

Drawing on theorizing and research suggesting that people are motivated to view their world as an orderly and predictable place in which people get what they deserve, the authors proposed that (a) random and uncontrollable bad outcomes will lower self-esteem and (b) this, in turn, will lead to the adoption of self-defeating beliefs and behaviors.

Four experiments demonstrated that participants who experienced or recalled bad (vs. good) breaks devalued their self-esteem (Studies 1a and 1b), and that decrements in self-esteem (whether arrived at through misfortune or failure experience) increase beliefs about deserving bad outcomes (Studies 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b). Five studies (Studies 3–7) extended these findings by showing that this, in turn, can engender a wide array of self-defeating beliefs and behaviors, including claimed self-handicapping ahead of an ability test (Study 3), the preference for others to view the self less favorably (Studies 4–5), chronic self-handicapping and thoughts of physical self-harm (Study 6), and choosing to receive negative feedback during an ability test (Study 7).

The current findings highlight the important role that concerns about deservingness play in the link between lower self-esteem and patterns of self-defeating beliefs and behaviors. The theoretical and practical implications of these findings are discussed.

{ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology | PDF }

psychology | July 7th, 2014 2:32 pm

This study compared the effectiveness of four classic moral stories in promoting honesty in 3- to 7-year-olds. Surprisingly, the stories of “Pinocchio” and “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” failed to reduce lying in children. In contrast, the apocryphal story of “George Washington and the Cherry Tree” significantly increased truth telling. Further results suggest that the reason for the difference in honesty-promoting effectiveness between the “George Washington” story and the other stories was that the former emphasizes the positive consequences of honesty, whereas the latter focus on the negative consequences of dishonesty.

{ Psychological Science | PDF }

art { Sara Cwynar, Print Test Panel (Darkroom Manuals), 2013 }

kids, psychology | July 2nd, 2014 1:41 pm

In the language of social psychology, the situationist view attributes behavior mainly to external, rather than internal forces. Hence, heroism and villainy are unrelated to individual differences in personality or even conscious decisions based on one’s values. This seems to imply a rather passive view of human behavior in which people are largely at the mercy of circumstances outside themselves, rather than rational actors capable of making choices. However, if features of the person can be disregarded in favour of situational forces, then it is very difficult to explain why it is that the same situation can elicit completely opposite responses from different people. This would seem to suggest that situations elicit either heroic or villainous responses in a random way that cannot be predicted, or that situational factors alone are insufficient to explain the choices that people make in difficult circumstances. An alternative view is that situations do not so much suppress the individual personality, as reveal the person’s latent potential (Krueger, 2008). Therefore, a dangerous situation for example might reveal one person’s potential for bravery and another’s potential for cowardice.

{ Eye on Psych | Continue reading }

psychology | July 1st, 2014 11:06 am

Four experiments examined the interplay of memory and creative cognition, showing that attempting to think of new uses for an object can cause the forgetting of old uses. […] Additionally, the forgetting effect correlated with individual differences in creativity such that participants who exhibited more forgetting generated more creative uses than participants who exhibited less forgetting. These findings indicate that thinking can cause forgetting and that such forgetting may contribute to the ability to think creatively.

{ APA/Psycnet | Continue reading }

art { Kazumasa Nagai }

ideas, psychology | June 30th, 2014 8:18 am

Individuals often wish to conceal their internal states. Anxiety over approaching a potential romantic partner, feelings of disgust over a disagreeable entrée served at a dinner party, or nervousness over delivering a public speech—all are internal states one may wish, for a variety of reasons, to keep private.

Research suggests that individuals are typically better at disguising their internal states than they believe—i.e., people are prone to an illusion of transparency, or a belief that their thoughts, feelings, and emotions are more apparent to others than is actually the case.

This illusion derives from the difficulty people have in getting beyond their own phenomenological experience when attempting to determine how they appear to others. The adjustment one makes from the ‘‘anchor’’ of one’s own phenomenology, like adjustments to anchors generally, tends to be insufficient. As a result, people exaggerate the extent to which their internal states ‘‘leak out’’ and overestimate the extent to which others can detect their private feelings. […]

As Miller and McFarland (1991) note, “in anxiety-provoking situations, it is often very difficult for people to believe that, despite feeling highly nervous, they do not appear highly nervous.” […]

[T]he realization that one’s nervousness is less apparent than one thinks may be useful in alleviating speech anxiety: If individuals can be convinced that their internal sensations are not manifested in their external appearance, one source of their anxiety can be attenuated, allowing them to relax and even improving the quality of their performance. Thus, speakers who know about the illusion of transparency may tend to give better speeches than speakers who do not.

{ Journal of Experimental Social Psychology | PDF }

burnt photograph glued to mirror { Douglas Gordon, Self-portrait of You + Me (Halle Berry), 2006 }

psychology | June 19th, 2014 11:48 am

We all know the awkward feeling when a conversation is disrupted by a brief silence. This paper studies why such moments can be unsettling. We suggest that silences are particularly disturbing if they disrupt the conversational flow.

A mere four-seconds silence (in a six-minute video clip) suffices to disrupt the conversational flow and make one feel distressed, afraid, hurt, and rejected. These effects occur despite participants’ unawareness of the short, single silence. […]

Finally, the present research reveals that although people do not consciously notice brief silences, they are influenced by conversa- tional disfluency in a way quite similar to ostracism experiences (e.g., Williams, 2001). That is, people report feeling more rejected and experience more negative emotions when a conversation is disrupted by a silence, rather than when it flows. Thus, disrupted flow can implicitly elicit feelings of rejection, confirming human sensitivity to social exclusion cues.

{ Journal of Experimental Social Psychology | PDF }

noise and signals, psychology, relationships | June 10th, 2014 2:17 pm

The paper, by Winegard et al., opens with the following vignette:

A bereaved wife every weekend walks one mile to place flowers on her deceased husband’s cemetery stone. Neither rain nor snow prevents her from making this trip, one she has been making for 2 years. However poignant the scene, and however high our temptation to exclude it from the cold logic of scientific scrutiny, it presents researchers with a perplexing puzzle that demands reflection. The deceased husband, despite all of his widow’s solicitude, cannot return to repay his wife’s devotion. Why waste time, energy, effort, resources—why, in other words, grieve for a social bond that can no longer compensate such dedication?

[…]

Their explanation is that bearing these costs acts as a signal. Drawing on Costly Signaling Theory (CST), they argue that paying these costs sends signals to other people regarding one’s value as a social partner. […] These signals, then, are actually – and unknowingly – directed toward new potential mates who might now consider the individual attractive as a long-term mate based on the quality, costliness, and honesty of the display.

{ The Evolutionary Psychology Blog | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships | June 6th, 2014 7:07 am

In his groundbreaking research, Geoffrey Miller (1999) suggests that artistic and creative displays are male-predominant behaviors and can be considered to be the result of an evolutionary advantage. The outcomes of several surveys conducted on jazz and rock musicians, contemporary painters, English writers (Miller, 1999), and scientists (Kanazawa, 2000) seem to be consistent with the Millerian hypothesis, showing a predominance of men carrying out these activities, with an output peak corresponding to the most fertile male period and a progressive decline in late maturity.

One way to evaluate the sex-related hypothesis of artistic and cultural displays, considered as sexual indicators of male fitness, is to focus on sexually dimorphic traits. One of them, within our species, is the 2nd to 4th digit length (2D:4D), which is a marker for prenatal testosterone levels.

This study combines the Millerian theories on sexual dimorphism in cultural displays with the digit ratio, using it as an indicator of androgen exposure in utero. If androgenic levels are positively correlated with artistic exhibition, both female and male artists should show low 2D:4D ratios. In this experiment we tested the association between 2D:4D and artistic ability by comparing the digit ratios of 50 artists (25 men and 25 women) to the digit ratios of 50 non-artists (25 men and 25 women).

Both male and female artists had significantly lower 2D:4D ratios (indicating high testosterone) than male and female controls. These results support the hypothesis that art may represent a sexually selected, typically masculine behavior that advertises the carrier’s good genes within a courtship context.

{ Evolutionary Psychology | PDF }

previously { Contrary to decades of archaeological dogma, many of the first artists were women }

art, hormones, psychology | June 4th, 2014 2:07 pm

Flirting is a class of courtship signaling that conveys the signaler’s intentions and desirability to the intended receiver while minimizing the costs that would accompany an overt courtship attempt. […]

Flirtation is marked by “mixed signals”: sidelong glances and indirect overtures. The human ethologist Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt, synthesizing decades of comparative study of human social behavior, reported that flirtatious gestures and expressions are cross-culturally consistent. He found that partially obscured actions such as quick looks and coy giggles behind a hand were common elements of flirtation in cultures from pastoral Africa to urban Europe to Polynesia. “Turning toward a person and then turning away,” he wrote, “are typical elements of human flirting behavior.” That indirect flirtation is recognizable as its own category of signaling suggests it might require a separate functional explanation. What do courting humans gain by making some courtship signals oblique?

Here we propose that the explanation for the subtlety of human courtship lies in the potential costs imposed by both intended and unintended receivers of courtship signals, either in the form of damage to social capital or of interference and intervention by third parties. […]

Third parties constitute an additional source of potential courtship costs. […] “Interception” occurs when a third party detects a signal and procures some information from it, as when a predator uses a prey animal’s mating call to locate the caller. […] Among courting humans, the most straightforward interception costs involve physical violence related to jealousy: Courting someone who already has a partner or admirer can bring swift and direct consequences if one is observed by that rival. […]

Signalers who skillfully assess and adjust to social context (i.e., good flirts) display their quality not through high-intensity displays that index physical prowess and condition, but through sensitive signal-to-context matching that indicates behavioral flexibility and social intelligence.

{ Evolutionary Psychology | PDF }

psychology, relationships | June 4th, 2014 1:36 pm