psychology

Even though boys express a wider range of emotions than girls do as infants, boys are typically discouraged from showing their emotions as they grow older due to traditional ideas about masculinity and gender roles. Crying frequency between boys and girls shows little difference until the age of eleven or twelve when girls overtake boys.

Being told that “big boys don’t cry,” boys are socialized against any display of strong emotion considered inappropriate while crying is specifically targeted as being “feminine” behaviour. There can be enormous culture differences over when and under what circumstances men and women are allowed to cry but men are often expected to be more stoic and unemotional in most situations. […]

Though crying among men seems more tolerated, there are still strong biases against men crying in public. In a 2001 study of undergraduate males in the United States, only 23 percent of males reported crying when feeling helpless as opposed to 58 percent of females with similar sex differences being noted in the United Kingdom and Israel.

{ Psychology Today | Continue reading }

photo { Stephen DiRado, Martha’s Vineyard/Beach People: Aquinnah, MA. }

genders, psychology | November 5th, 2013 2:47 pm

Our ability to exhibit self-control to avoid cheating or lying is significantly reduced over the course of a day, making us more likely to be dishonest in the afternoon than in the morning, according to findings published in Psychological Science.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Johan Rosenmunthe }

psychology | October 30th, 2013 12:55 pm

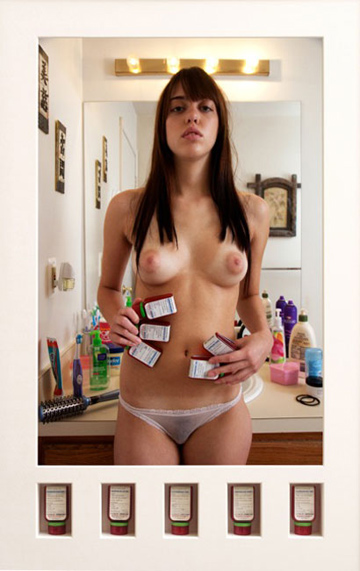

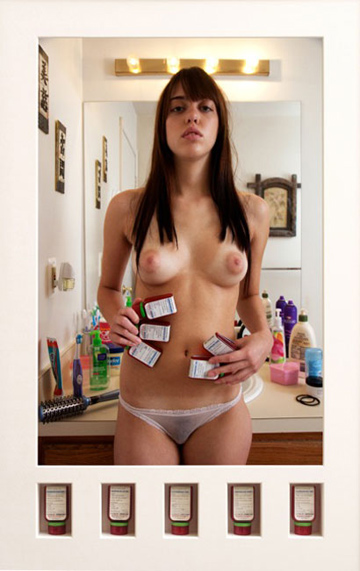

Earlier studies already showed that people that just experienced or recalled an embarrassing situation — that is a public action that observers could consider as foolish or inappropriate — often feel motivated to avoid social contact or to repair their image. Sunglasses and restorative cosmetics could help with that. A team of researchers now investigated the actual effectiveness of these coping strategies. […]

Hiding the face and repairing the face weren’t equally effective in these experiments. Face restoring products seemed to relieve feelings of embarrassment and restore willingness to interact with others. Simply hiding the face didn’t seem to help.

{ United-Academics | Continue reading }

faces, psychology | October 25th, 2013 11:14 am

There is a motif, in fiction and in life, of people having wonderful things happen to them, but still ending up unhappy. We can adapt to anything, it seems—you can get your dream job, marry a wonderful human, finally get 1 million dollars or Twitter followers—eventually we acclimate and find new things to complain about.

If you want to look at it on a micro level, take an average day. You go to work; make some money; eat some food; interact with friends, family or co-workers; go home; and watch some TV. Nothing particularly bad happens, but you still can’t shake a feeling of stress, or worry, or inadequacy, or loneliness.

According to Dr. Rick Hanson, a neuropsychologist, our brains are naturally wired to focus on the negative, which can make us feel stressed and unhappy even though there are a lot of positive things in our lives. True, life can be hard, and legitimately terrible sometimes. Hanson’s book (a sort of self-help manual grounded in research on learning and brain structure) doesn’t suggest that we avoid dwelling on negative experiences altogether—that would be impossible. Instead, he advocates training our brains to appreciate positive experiences when we do have them, by taking the time to focus on them and install them in the brain. […]

The simple idea is that we we all want to have good things inside ourselves: happiness, resilience, love, confidence, and so forth. The question is, how do we actually grow those, in terms of the brain? It’s really important to have positive experiences of these things that we want to grow, and then really help them sink in, because if we don’t help them sink in, they don’t become neural structure very effectively. So what my book’s about is taking the extra 10, 20, 30 seconds to enable everyday experiences to convert to neural structure so that increasingly, you have these strengths with you wherever you go. […]

As our ancestors evolved, they needed to pass on their genes. And day-to-day threats like predators or natural hazards had more urgency and impact for survival. On the other hand, positive experiences like food, shelter, or mating opportunities, those are good, but if you fail to have one of those good experiences today, as an animal, you would have a chance at one tomorrow. But if that animal or early human failed to avoid that predator today, they could literally die as a result.

That’s why the brain today has what scientists call a negativity bias.[…] For example, negative information about someone is more memorable than positive information, which is why negative ads dominate politics. In relationships, studies show that a good, strong relationship needs at least a 5:1 ratio of positive to negative interactions.

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

photo and pill bottles { Richard Kern }

brain, guide, psychology | October 25th, 2013 10:27 am

For all the subtlety of its characterization, the book doesn’t just provide a chilling psychological portrait, it conjures up an entire world. The clue is in the name: On some level we’re to imagine that the American Psychiatric Association is a body with real powers, that the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual” is something that might actually be used, and that its caricature of our inner lives could have serious consequences. Sections like those on the personality disorders offer a terrifying glimpse of a futuristic system of repression, one in which deviance isn’t furiously stamped out like it is in Orwell’s unsubtle Oceania, but pathologized instead. Here there’s no need for any rats, and the diagnostician can honestly believe she’s doing the right thing; it’s all in the name of restoring the sick to health. DSM-5 describes a nightmare society in which human beings are individuated, sick, and alone.

{ The New Inquiry | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology | October 23rd, 2013 1:56 pm

The explosion in music consumption over the last century has made ‘what you listen to’ an important personality construct – as well as the root of many social and cultural tribes – and, for many people, their self-perception is closely associated with musical preference. We would perhaps be reluctant to admit that our taste in music alters - softens even - as we get older.

Now, a new study suggests that - while our engagement with it may decline - music stays important to us as we get older, but the music we like adapts to the particular ‘life challenges’ we face at different stages of our lives.

It would seem that, unless you die before you get old, your taste in music will probably change to meet social and psychological needs.

One theory put forward by researchers, based on the study, is that we come to music to experiment with identity and define ourselves, and then use it as a social vehicle to establish our group and find a mate, and later as a more solitary expression of our intellect, status and greater emotional understanding.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Olivia Locher }

music, photogs, psychology, time | October 15th, 2013 11:44 am

Shoppers are more likely to buy a product from a different location when a pleasant sound coming from a particular direction draws attention to the item, according to a new study in the Journal of Consumer Research.

“Suppose that you are standing in a supermarket aisle, choosing between two packets of cookies, one placed nearer your right side and the other nearer your left. While you are deciding, you hear an in-store announcement from your left, about store closing hours,” write authors Hao Shen (Chinese University of Hong Kong) and Jaideep Sengupta (Hong Kong University of Science and Technology). “Will this announcement, which is quite irrelevant to the relative merits of the two packets of cookies, influence your decision?”

In the example above, most consumers would choose the cookies on the left because consumers find it easier to visually process a product when it is presented in the same spatial direction as the auditory signal, and people tend to like things they find easy to process.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

economics, noise and signals, psychology | October 15th, 2013 11:22 am

psychology, relationships | October 8th, 2013 3:15 pm

There are many theories about why humans cry ranging from the biophysical to the evolutionary. One of the most compelling hypotheses is Jeffrey Kottler’s, discussed at length in his 1996 book The Language of Tears. Kottler believes that humans cry because, unlike every other animal, we take years and years to be able to fend for ourselves. Until that time, we need a behavior that can elicit the sympathetic consideration of our needs from those around us who are more capable (read: adults). We can’t just yell for help though—that would alert predators to helpless prey—so instead, we’ve developed a silent scream: we tear up. […]

In a study published in 2000, Vingerhoets and a team of researchers found that adults, unlike children, rarely cry in public. They wait until they’re in the privacy of their homes—when they are alone or, at most, in the company of one other adult. On the face of it, the “crying-as-communication” hypothesis does not fully hold up, and it certainly doesn’t explain why we cry when we’re alone, or in an airplane surrounded by strangers we have no connection to. […]

In the same 2000 study, Vingerhoet’s team also discovered that, in adults, crying is most likely to follow a few specific antecedents. When asked to choose from a wide range of reasons for recent spells of crying, participants in the study chose “separation” or “rejection” far more often than other options, which included things like “pain and injury” and “criticism.” Also of note is that, of those who answered “rejection,” the most common subcategory selected was “loneliness.”

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

photo { Adrienne Grunwald }

eyes, psychology, water | October 8th, 2013 2:31 pm

Lying well is hard — but not in the way you might think.

We usually look for nervousness as one of the signs of lying. Like the person is worried about getting caught. But that’s actually a weak predictor.

Some people are so confident they don’t fear getting caught. Others are great at hiding it.

Some get nervous when questioned so you get false positives. And others are lying to themselves — so they show no signs of deliberate deception.

So lying isn’t necessarily hard in terms of stress. But it is hard in terms of “cognitive load.” What’s that mean?

Lying is hard because it makes you think. You need to think up the lies. That’s extra work.

Looking for nervousness can be a wild goose chase. Looking for signs of thinking hard can be a great strategy.

[…]

They tend not to move their arms and legs so much, cut down on gesturing, repeat the same phrases, give shorter and less detailed answers, take longer before they start to answer, and pause and hesitate more. In addition, there is also evidence that they distance themselves from the lie, causing their language to become more impersonal. As a result, liars often reduce the number of times that they say words such as “I,” “me,” and “mine,” and use “him” and “her” rather than people’s names. Finally, is increased evasiveness, as liars tend to avoid answering the question completely, perhaps by switching topics or by asking a question of their own.

To detect deception, forget about looking for signs of tension, nervousness, and anxiety. Instead, a liar is likely to look as though they are thinking hard for no good reason, conversing in a strangely impersonal tone, and incorporating an evasiveness that would make even a politician or a used-car salesman blush.

{ Barking Up The Wrong Tree | Continue reading }

guide, psychology | September 24th, 2013 1:34 pm

Hyperlink cinema uses cinematic devices such as flashbacks, interspersing scenes out of chronological order, split screens and voiceovers to create an interacting social network of storylines and characters across space and time. […]

Krems and Dunbar wondered if the social group sizes and properties of social networks in such films differ vastly from the real world or classic fiction. They set out to see if the films can side-step the natural cognitive constraints that limit the number and quality of social relationships people can generally manage. Previous studies showed for instance that conversation groups of more than four people easily fizzle out. Also, Dunbar and other researchers found that someone can only maintain a social network of a maximum of 150 people, which is further layered into 4 to 5 people (support group), 12 to 15 people (sympathy group), and 30 to 50 people (affinity group).

Twelve hyperlink films and ten female interest conventional films as well as examples from the real world and classical fiction were therefore analyzed. Krems and Dunbar discovered that all examples rarely differed and all followed the same general social patterns found in the conventional face-to-face world. Hyperlink films had on average 31.4 characters that were important for the development of plot, resembling the size of an affinity group in contemporary society. Their cast lists also featured much the same number of speaking characters as a Shakespeare play (27.8 characters), which reflects a broader, less intimate sphere of action. Female interest films had 20 relevant characters on average, which corresponds with the sympathy group size and mimics female social networks in real life.

{ Springer | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships | September 24th, 2013 1:32 pm

By about 1900, the need for child labour had declined, so children had a good deal of free time. But then, beginning around 1960 or a little before, adults began chipping away at that freedom by increasing the time that children had to spend at schoolwork and, even more significantly, by reducing children’s freedom to play on their own, even when they were out of school and not doing homework. Adult-directed sports for children began to replace ‘pickup’ games; adult-directed classes out of school began to replace hobbies; and parents’ fears led them, ever more, to forbid children from going out to play with other kids, away from home, unsupervised. There are lots of reasons for these changes but the effect, over the decades, has been a continuous and ultimately dramatic decline in children’s opportunities to play and explore in their own chosen ways.

Over the same decades that children’s play has been declining, childhood mental disorders have been increasing.

{ Aeon | Continue reading }

kids, psychology | September 18th, 2013 12:50 pm

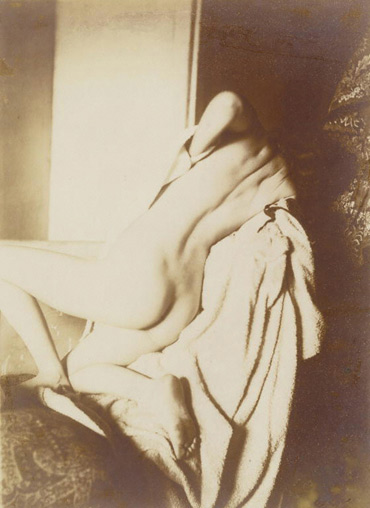

For a common affliction that strikes people of every culture and walk of life, schizophrenia has remained something of an enigma. Scientists talk about dopamine and glutamate, nicotinic receptors and hippocampal atrophy, but they’ve made little progress in explaining psychosis as it unfolds on the level of thoughts, beliefs, and experiences. Approximately one percent of the world’s population suffers from schizophrenia. Add to that the comparable numbers of people who suffer from affective psychoses (certain types of bipolar disorder and depression) or psychosis from neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease. All told, upwards of 3% of the population have known psychosis first-hand. These individuals have experienced how it transformed their sensations, emotions, and beliefs. […]

There are several reasons why psychosis has proved a tough nut to crack. First and foremost, neuroscience is still struggling to understand the biology of complex phenomena like thoughts and memories in the healthy brain. Add to that the incredible diversity of psychosis: how one psychotic patient might be silent and unresponsive while another is excitable and talking up a storm. Finally, a host of confounding factors plague most studies of psychosis. Let’s say a scientist discovers that a particular brain area tends to be smaller in patients with schizophrenia than healthy controls. The difference might have played a role in causing the illness in these patients, it might be a direct result of the illness, or it might be the result of anti-psychotic medications, chronic stress, substance abuse, poor nutrition, or other factors that disproportionately affect patients.

One intriguing approach is to study psychosis in healthy people. […] This approach is possible because schizophrenia is a very different illness from malaria or HIV. Unlike communicable diseases, it is a developmental illness triggered by both genetic and environmental factors. These factors affect us all to varying degrees and cause all of us – clinically psychotic or not – to land somewhere on a spectrum of psychotic traits. Just as people who don’t suffer from anxiety disorders can still differ in their tendency to be anxious, nonpsychotic individuals can differ in their tendency to develop delusions or have perceptual disturbances. One review estimates that 1 to 3% of nonpsychotic people harbor major delusional beliefs, while another 5 to 6% have less severe delusions. An additional 10 to 15% of the general population may experience milder delusional thoughts on a regular basis.

{ Garden of the Mind | Continue reading }

photo { Edgar Degas, After the Bath, Woman Drying Her Back, 1896 }

mystery and paranormal, neurosciences, psychology | September 18th, 2013 7:24 am

{ The Five Cognitive Distortions of People Who Get Stuff Done | PDF }

psychology, visual design | September 12th, 2013 9:08 pm

When I eventually returned to my desk at Keele University School of Psychology I wondered why it was that people swear in response to pain. Was it a coping mechanism, an outlet for frustration, or what? […]

Professor Timothy Jay of Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in the States […] has forged a career investigating why people swear and has written several books on the topic. His main thesis is that swearing is not, as is often argued, a sign of low intelligence and inarticulateness, but rather that swearing is emotional language.

{ The Pyschologist | Continue reading }

Linguistics, psychology | September 10th, 2013 2:11 pm

As it turns out, high-functioning sociopaths are full of handy lifestyle tips. […]

After being hired at an elite law firm, Ms Thomas exploited her company’s “non-existent” vacation policy by taking long weekends and lengthy vacations abroad. “People were implicitly expected not to take vacations, but I had my own lifelong policy of following only explicit rules, and then only because they’re easiest to prove against me,” she explains.

How to apply to your own life: Ignore “suggested donation” pleas at museums, always help yourself to more food and drinks at dinner parties and recline your seat all the way back when flying. […]

Ms Thomas’s opportunism applies to the social as much as the professional realm. “I have learned that it is important always to have a catalogue of at least five personal stories of varying length in order to avoid the impulse to shoehorn unrelated titbits into existing conversations,” she writes. “Social-event management feels very much like classroom or jury management to me; it’s all about allowing me to present myself to my own best advantage.” […]

One of Ms Thomas’s favourite activities is attending academic conferences. Since she doesn’t teach at a top-tier school, she captures her colleagues’ attention by other means: “Everything about the way I present myself is extremely calculated,” she writes. “I am careful to wear something that will draw attention, like jeans and cowboy boots while everyone else is wearing business attire.” The goal, Ms Thomas says, is “to indicate that I’m not interested in being judged by the usual standards.”

{ The Economist | Continue reading }

guide, psychology | August 21st, 2013 2:43 pm

The economics of “happiness” shares a feature with behavioral economics that raises questions about its usefulness in public policy analysis. What happiness economists call “habituation” refers to the fact that people’s reported well-being reverts to a base level, even after major life events such as a disabling injury or winning the lottery. What behavioral economists call “projection bias” refers to the fact that people systematically mistake current circumstances for permanence, buying too much food if shopping while hungry for example. Habituation means happiness does not react to long-term changes, and projection bias means happiness over-reacts to temporary changes. I demonstrate this outcome by combining responses to happiness questions with information about air quality and weather on the day and in the place where those questions were asked. The current day’s air quality affects happiness while the local annual average does not. Interpreted literally, either the value of air quality is not measurable using the happiness approach or air quality has no value. Interpreted more generously, projection bias saves happiness economics from habituation, enabling its use in public policy.

{ National Bureau of Economic Research }

economics, ideas, psychology | August 21st, 2013 3:26 am

Researchers at the University of Kentucky were interested in the link between low glucose levels and aggressive behavior… […]

When you go several hours without eating, your blood sugar drops. Once it falls below a certain point, glucose-sensing neurons in your ventromedial hypothalamus, a brain region involved in feeding, are notified and activated resulting in level fluctuations of several different hormones. Ghrelin, a hormone that increases expression when blood sugar gets low and stimulates appetite through actions of the hypothalamus, has been shown to block the release of the neurotransmitter serotonin. The serotonin system is incredibly complex and contributes to a number of different central nervous system functions. One of the many hats this neurotransmitter wears is modulation of emotional state, including aggression. […]

If you have a predisposition to aggression, low serotonin levels circulating in your brain may lead to altered communications between brain regions that wrangle aggressive behavior.

{ Synaptic Scoop | Continue reading }

food, drinks, restaurants, neurosciences, psychology | August 19th, 2013 5:02 pm

guide, psychology | August 15th, 2013 2:49 pm

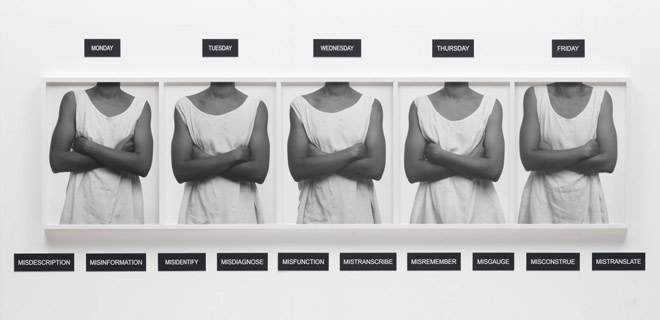

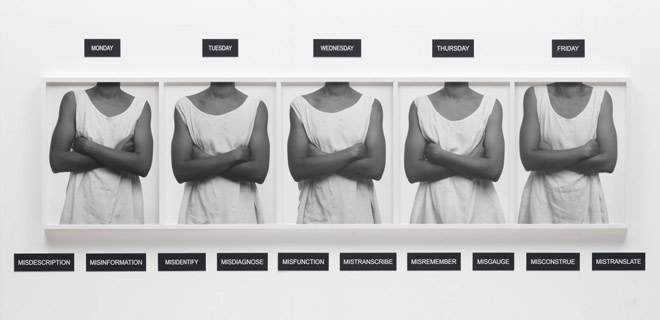

In two experiments we showed that exposure to an incidental black and white visual contrast leads people to think in a “black and white” manner, as indicated by more extreme moral judgments.

Participants who were primed with a black and white checkered background while considering a moral dilemma (Experiment 1) or a series of social issues (Experiment 2) gave ratings that were significantly further from the response scale’s mid-point, relative to participants in control conditions without such priming.

These findings suggest that in addition to affective cues and gut feelings, non-affective cues relating to processing style can influence moral judgments.

{ ScienceDirect }

art { Lorna Simpson }

psychology | August 7th, 2013 11:45 am