psychology

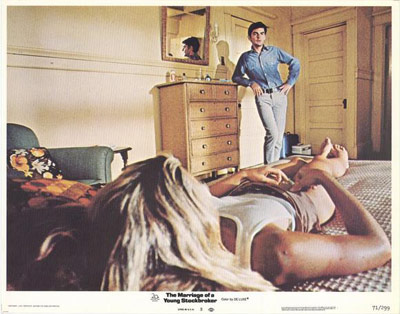

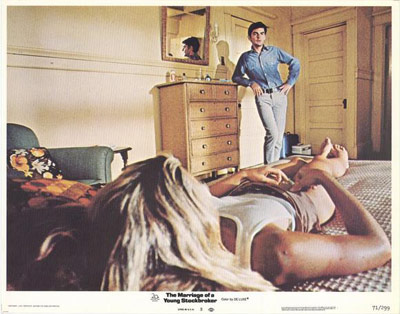

Researchers from the University of North Carolina have shown that coupling and sexual behavior are related to our gendered behavior.

What they found is that couples who are showing highly gendered behavior (so highly masculine men and highly feminine women) more often select one another as sexual partners and have intercourse more quickly, compared to couples who show less distinct gendered behavior. The latter are the slowest to have sex and the quickest to break up. The authors argue that the distinct gender differences between highly masculine men and highly feminine women may be needed to incite, and maintain, (sexual) interest in a relationship.

So, your love life may just be the result of how much of a macho man or a girly girl you grew up to be.

{ United Academics | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships, sex-oriented | January 7th, 2013 12:56 pm

Member-to-group comparisons are prevalent in everyday life. A person might consider whether one politician would make a better president than other candidates, whether one home is more suitable than other prospective homes on the market, whether one food item is healthier than others, or whether one vacation spot is more desirable than others. In turn, the outcomes of such comparisons have important consequences for a person’s choices, decisions, moods, thoughts, and, ultimately, welfare. Indeed, rational models of choice are predicated on the idea that human beings can maximize their utility by identifying the best and worst options in a choice set.

However, recent work by Klar and his colleagues suggests that people are far from unbiased in their comparisons. Individual members of positively valenced groups (e.g., healthy foods, good politicians) are rated better and individual members of negatively valenced groups (e.g., unhealthy foods, bad politicians) are rated worse than the group average, in defiance of simple mathematical rules stating that the average of the individual members must equal the group average. In one of the first studies demonstrating these nonselective inferiority and superiority biases, Giladi and Klar had shoppers evaluate randomly selected pleasant-smelling or unpleasant-smelling soaps and found that any given pleasant soap was rated better than the rest of the group, and any given unpleasant soap was rated worse than the rest of the group. These effects have since been observed with other object categories, including desirable and undesirable acquaintances, restaurants, social groups, pieces of furniture, hotels, and songs, and thus appear to be highly robust and reliable.

In explaining these nonselective biases, Giladi and Klar proposed that when one member of a positive or negative group is compared with others (e.g., how does good restaurant A compare with other good restaurants B and C?), that member is evaluated against a standard that is one part local (restaurants B and C) and one part general (all other restaurants, including bad ones). Thus, although the member that is being evaluated should be compared only with the normatively appropriate local standard, it is actually compared with a hybrid standard that includes both the local and the general standard. Consequently, almost any member of a positive group will be rated better than others (because the general standard is more negative than the local standard), and almost any member of a negative group will be rated worse than others (because the general standard is more positive than the local standard).

In this article, I propose an additional reason (beyond the confusion of local and general standards) why almost any group member is rated more extremely than others in its group.

{ APS/SAGE | Continue reading }

photo { Lise Sarfati }

psychology | December 18th, 2012 2:21 pm

While risk research focuses on actions that put people at risk, this paper introduces the concept of “passive risk”—risk brought on or magnified by inaction. […]

Avoidance of regret (more precisely “perceived future regret”/ “anticipated regret”) is a major factor in most inaction biases. Support for this idea can be found in Norm Theory which claims that inactions are usually perceived as “normal”, in contrast to actions, which are viewed as “abnormal” and therefore elicit more counterfactual thinking and regret. People regret actions (with bad outcomes) more than inactions, so it is clear why people who try to avoid regret prefer inaction in situations when actions may lead to unwanted outcomes. However, in passive risk taking behavior we refer to situations in which actions can only lead to positive/neutral outcomes, so regret avoidance cannot be the cause of inaction in these instances. People do not avoid cancer tests because they fear they might feel regret after having the tests done. […]

Procrastination is defined as “the act of needlessly delaying tasks to the point of experiencing subjective discomfort.” It may seem as though passive risk taking is essentially procrastination, but there is a major difference: the procrastinator knows that eventually he will have to complete the task at hand, the decision to act has already been established—it is only the actual doing that is delayed. In passive risk taking people decide “not to act,” or in some cases “not act for now.”

{ Judgment and Decision Making | Continue reading }

photos { Paul Kooiker }

psychology | December 12th, 2012 2:25 am

According to new research, playing hard to get tests the commitment and quality of any would-be mate. Researchers identified 58 different hard-to-get strategies used, from on/off flirting and being snooty to using voicemail to intercept calls from would-be partners.

“Playing hard to get might be one way that people – women in particular – can test their prospective mate’s commitment and to manipulate their prospective mates to obtain what – or whom – they want,” said the psychologists who carried out the study. “We revealed that the more unavailable a person is, the more people are willing to invest in them.”

In the study, reported in the European Journal of Personality, the researchers carried out four separate projects involving more than 1,500 people, looking at playing hard to get as a mating strategy to see how and why it works. […]

Women used the tactics more than men. That, say the researchers, could be because women are trying to learn more information about a potential mate as they have more to lose in terms of pregnancy. […]

Appearing highly self-confident was the top-ranked tactic, followed by talking to other people and, third, withholding sex.

{ Independent | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships | December 10th, 2012 11:34 am

With a little practice, one could learn to tell a lie that may be indistinguishable from the truth.

New Northwestern University research shows that lying is more malleable than previously thought, and with a certain amount of training and instruction, the art of deception can be perfected.

People generally take longer and make more mistakes when telling lies than telling the truth, because they are holding two conflicting answers in mind and suppressing the honest response, previous research has shown. Consequently, researchers in the present study investigated whether lying can be trained to be more automatic and less task demanding.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships | December 7th, 2012 2:59 pm

People who recall being absolved of their sins, are more likely to donate money to the church, according to research published today in the journal Religion, Brain and Behavior.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Michael Wolf }

economics, psychology | December 6th, 2012 10:05 am

For thousands of years, a core pursuit of medical science has been the careful observation of physical symptoms and signs. Through these observations, supplemented more recently by investigative techniques, an understanding of how symptoms and signs are generated by disease has developed. However, there is a group of patients with symptoms and signs that, from the earliest medical records to the present day, elude a diagnosis with a typical ‘organic’ disease. This is not simply because of an absence of pathology after sufficient investigation, rather that symptoms themselves are inconsistent with those occurring in typical disease. In times past, these symptoms were said to be ‘hysterical’, a term now replaced by the less pejorative but no more enlightening labels: ‘medically unexplained’, ‘psychogenic’, ‘conversion’, ‘non-organic’ and ‘functional’.

There are numerous historical examples of patients identified as having hysteria who would now be diagnosed with an organic medical disorder. Some have assumed that this process of salvaging patients from (mis)diagnosis with hysteria would continue inexorably until a ‘proper’ medical diagnosis was achieved. Slater (1965), in his influential paper on the topic, described the diagnosis of hysteria as ‘a disguise for ignorance and a fertile source of clinical error’. In other words, with increasing medical knowledge, all patients would be rescued from a diagnostic category that did little more than assert that they were ‘too difficult’.

This has not come to pass (Stone et al., 2005). Recent epidemiological work has demonstrated that neurologists continue to diagnose a ‘non-organic’ disorder in ∼16% of their patients, making this the second most common diagnosis of neurological outpatients.

{ Brain/Oxford Journals | Continue reading }

photo { Paul Himmel }

health, neurosciences, psychology | December 5th, 2012 3:17 pm

Uptalk is the use of a rising, questioning intonation when making a statement, which has become quite prevalent in contemporary American speech. Women tend to use uptalk more frequently than men do, though the reasons behind this difference are contested. I use the popular game show Jeopardy! to study variation in the use of uptalk among the contestants’ responses, and argue that uptalk is a key way in which gender is constructed through interaction. While overall, Jeopardy! contestants use uptalk 37 percent of the time, there is much variation in the use of uptalk. The typical purveyor of uptalk is white, young, and female. Men use uptalk more when surrounded by women contestants, and when correcting a woman contestant after she makes an incorrect response. Success on the show produces different results for men and women. The more successful a man is, the less likely he is to use uptalk; the more successful a woman is, the more likely she is to use uptalk.

{ SAGE }

photo { Billy Kidd }

genders, psychology | December 5th, 2012 3:02 pm

When I was a kid, probably about 9 or 10 [years old], we went to an Indian restaurant for dinner. Just as my dad was about to pay, he suddenly tinked his spoon against his glass and stood up. The whole restaurant went silent. My dad said, “I’d just like to thank you all for coming; some from just round the corner, some from much further afield. You’re all most welcome to join us for a little drinks reception across the road.’

And so an entire restaurant of strangers who had never seen us before were all applauding wildly because they didn’t want to be seen as gatecrashers. We just took off. He [told me] we’re not going to the pub really and [explained that his] old friend Malcolm had [just opened a new pub across the street].

[…]

If you’re an intelligent psychopath and violent [and get a good start], there are any number of exciting occupations, anything from special forces operative to head of a criminal syndicate.

{ Kevin Dutton/Time | Continue reading }

psychology | November 27th, 2012 3:01 pm

Young children are inclined to see purpose in the natural world. Ask them why we have rivers, and they’ll likely tell you that we have rivers so that boats can travel on them (an example of a “teleological explanation”). […] A new study with 80 physical scientists finds that they too have a latent tendency to endorse similar teleological explanations for why nature is the way it is. They label those explanations as false most of the time, but put them under time pressure, and their child-like, quasi-religious beliefs shine through.

Deborah Kelemen and her colleagues presented 80 scientists (including physicists, chemists and geographers) with 100 one-sentence statements and their task was to say if each one was true or false. Among the items were teleological statements about nature, such as “Trees produce oxygen so that animals can breathe”. Crucially, half the scientists had to answer under time pressure - just over 3 seconds for each statement - while the others had as long as they liked. There were also control groups of college students and the general public. […]

When they were rushed, the scientists endorsed 29 per cent of teleological statements compared with 15 per cent endorsed by the un-rushed scientists. This is consistent with the idea that a tendency to endorse teleological beliefs lingers in the scientists’ minds. This unscientific thinking is usually suppressed, but time pressure undermines that conscious suppression. […]

Scientists who admitted having religious beliefs, or beliefs about Mother Nature being one big organism, were more prone than most to endorsing teleological explanation under time pressure.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

psychology | November 27th, 2012 3:00 pm

In a year or two, augmented reality (AR) headsets such as Google Glass may double up as a virtual dieting pill. New research from the University of Tokyo shows that a very simple AR trick can reduce the amount that you eat by 10% — and yes, the same trick, used in the inverse, can be used to increase food consumption by 15%, too.

The AR trick is very simple: By donning the glasses, the University of Tokyo’s special software “seamlessly” scales up the size of your food. […]

It has been shown time and time again that large plates and large servings encourage you to consume more. In one study, restaurant-goers ate more food when equipped with smaller forks; but at home, the opposite is true. In another study, it was shown that you eat more food if the color of your plate matches what you’re eating.

{ ExtremeTech | Continue reading }

food, drinks, restaurants, psychology, technology | November 21st, 2012 11:06 am

It’s not surprising that social norms influence consumer behavior. When everybody else wants to spend $400 on the new iPad, it makes sense that you’ll be more willing to spend $400 on a new iPad. The question is, how far does this social influence extend?

A new study led by Ivo Vlaev examines how social norms influence spending on a good that ought to be on the opposite end of the social influence spectrum from consumer electronics: pain reduction. If somebody stabs you in the foot with a steak knife, you would assume your desire to alleviate that pain has nothing to do with the decision of somebody else who suffered the same stabbing. But that’s not what Vlaev and his team found. When it came to avoiding a painful electric shock, people didn’t just make decisions based their own pain, they also took into account how much other people wanted to reduce that same pain. […]

The fact that our desire to alleviate pain is subject to social influences has important implications for health care systems. For example, if it seems like back pain is something you’re expected to live with, people might be less willing to seek treatment for it.

{ peer-reviewed by my neurons | Continue reading }

health, psychology | November 20th, 2012 8:02 am

Psychologists Segal-Caspi and colleagues took 118 female Israeli students and videotaped them walking into a room and reading a weather forecast. Then other students - male and female - judged the ‘targets’ on attractiveness, but also tried to work out their personality, purely based on 60 seconds of video.

So what happened?

The judges judged prettier women as having stereotypically ‘better’ personality traits e.g. less neurotic and more friendly. Interestingly, both male and female judges did this, and there were no significant differences between the genders.

So there’s a tendency to think that those we find attractive are also beautiful on the inside.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

psychology | November 20th, 2012 8:00 am

It’s all about the fact that people want to achieve two things at the same time. We want to think of ourselves as honest, wonderful people, and then we want to benefit from cheating. Our ability to rationalize our own actions can actually help us be more dishonest while thinking of ourselves as honest. So the idea that everybody else does it, or the idea that nobody is really going to suffer, or the idea that the entity you are stealing from is actually a bad entity, or the idea that you don’t see it—all of those things help people be dishonest.

{ Daniel Ariely/The Politic | Continue reading }

economics, psychology, scams and heists | November 18th, 2012 4:11 pm

The eminent criminal psychologist and creator of the widely used Psychopathy Checklist paused before answering. “I think, in general, yes, society is becoming more psychopathic,” he said. “I mean, there’s stuff going on nowadays that we wouldn’t have seen 20, even 10 years ago. Kids are becoming anesthetized to normal sexual behavior by early exposure to pornography on the Internet. Rent-a-friend sites are getting more popular on the Web, because folks are either too busy or too techy to make real ones. … The recent hike in female criminality is particularly revealing. And don’t even get me started on Wall Street.”

{ The Chronicle of Higher Education | Continue reading }

psychology | November 6th, 2012 10:04 am

Cotard’s Syndrome is the delusional belief that one is dead or missing internal organs or other body parts. Those who suffer from this “delusion of negation” deny their own existence. The eponymous French neurologist Jules Cotard called it le délire de négation (”negation delirium”). […]

In a review of 100 cases, Berrios and Luque (1995) found that: “Depression was reported in 89% of subjects; the most common nihilistic delusions concerned the body (86%) and existence (69%).”

{ The Neurocritic | Continue reading }

image { Chris Scarborough }

psychology | November 6th, 2012 6:16 am

Research shows that friends influence how girls and women view and judge their own body weight, shape and size. What Wasylkiw and Williamson’s work sheds light on, is how much of a young woman’s body concerns are shaped by her perceptions of peers’ concerns with their own body versus her peers’ actual body concerns. […]

They found that the more women felt under pressure to be thin, the more likely they were to have body image concerns, irrespective of their actual weight and shape. Interestingly, body talk between friends that focussed on exercise was related to lower body dissatisfaction.

{ Springer | Continue reading }

health, psychology | November 5th, 2012 3:02 pm

Contemplating death doesn’t necessarily lead to morose despondency, fear, aggression or other negative behaviors, as previous research has suggested. […]

The awareness of mortality can motivate people to enhance their physical health and prioritize growth-oriented goals; live up to positive standards and beliefs; build supportive relationships and encourage the development of peaceful, charitable communities; and foster open-minded and growth-oriented behaviors.

{ Improbable Research | Continue reading }

photo { Sasha Kurmaz }

psychology | October 31st, 2012 11:49 am

This study offers the first combined quantitative assessment of suicide terrorists and rampage, workplace, and school shooters who attempt suicide, to investigate where there are statistically significant differences and where they appear almost identical. Suicide terrorists have usually been assumed to be fundamentally different from rampage, workplace, and school shooters.

Many scholars have claimed that suicide terrorists are motivated purely by ideology, not personal problems, and that they are not even suicidal. This study’s focus was on attacks and attackers in the United States from 1990 to 2010 and concluded that the differences between these offenders were largely superficial. Prior to their attacks, they struggled with many of the same personal problems, including social marginalization, family problems, work or school problems, and precipitating crisis events.

{ Homicide Studies/SAGE | Continue reading }

guns, horror, psychology | October 30th, 2012 3:45 pm

Which personality traits are associated with physical attractiveness? Recent findings suggest that people high in some dark personality traits, such as narcissism and psychopathy, can be physically attractive. But what makes them attractive?

Studies have confounded the more enduring qualities that impact attractiveness (i.e., unadorned attractiveness) and the effects of easily manipulated qualities such as clothing (i.e., effective adornment). In this multimethod study, we disentangle these components of attractiveness, collect self-reports and peer reports of eight major personality traits, and reveal the personality profile of people who adorn themselves effectively. Consistent with findings that dark personalities actively create positive first impressions, we found that the composite of the Dark Triad—Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy—correlates with effective adornment. This effect was also evident for psychopathy measured alone.

This study provides the first experimental evidence that dark personalities construct appearances that act as social lures—possibly facilitating their cunning social strategies.

{ Social Psychological and Personality Science /SAGE }

charcoal and pastel on paper { Johannes Kahrs, Untitled (figure with star), 2007 }

psychology | October 30th, 2012 3:31 pm