psychology

Several theories claim that dreaming is a random by-product of REM sleep physiology and that it does not serve any natural function.

Phenomenal dream content, however, is not as disorganized as such views imply. The form and content of dreams is not random but organized and selective: during dreaming, the brain constructs a complex model of the world in which certain types of elements, when compared to waking life, are underrepresented whereas others are over represented. Furthermore, dream content is consistently and powerfully modulated by certain types of waking experiences.

On the basis of this evidence, I put forward the hypothesis that the biological function of dreaming is to simulate threatening events, and to rehearse threat perception and threat avoidance.

To evaluate this hypothesis, we need to consider the original evolutionary context of dreaming and the possible traces it has left in the dream content of the present human population. In the ancestral environment, human life was short and full of threats. Any behavioral advantage in dealing with highly dangerous events would have increased the probability of reproductive success. A dream-production mechanism that tends to select threatening waking events and simulate them over and over again in various combinations would have been valuable for the development and maintenance of threat-avoidance skills.

Empirical evidence from normative dream content, children’s dreams, recurrent dreams, nightmares, post traumatic dreams, and the dreams of hunter-gatherers indicates that our dream-production mechanisms are in fact specialized in the simulation of threatening events, and thus provides support to the threat simulation hypothesis of the

{ Antti Revonsuo/Behavioral and Bain Sciences | PDF }

archives, psychology, science, theory | March 19th, 2012 3:02 pm

According to a paper just published (but available online since 2010), we haven’t found any genes for personality.

The study was a big meta-analysis of a total of 20,000 people of European descent. In a nutshell, they found no single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with any of the “Big 5″ personality traits of Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to Experience, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness. There were a couple of very tenuous hits, but they didn’t replicate.

Obviously, this is bad news for people interested in the genetics of personality.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

image { Pole Edouard }

genes, psychology | March 19th, 2012 12:15 pm

New support for the value of fiction is arriving from an unexpected quarter: neuroscience.

Brain scans are revealing what happens in our heads when we read a detailed description, an evocative metaphor or an emotional exchange between characters. Stories, this research is showing, stimulate the brain and even change how we act in life.

Researchers have long known that the “classical” language regions, like Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area, are involved in how the brain interprets written words. What scientists have come to realize in the last few years is that narratives activate many other parts of our brains as well, suggesting why the experience of reading can feel so alive. Words like “lavender,” “cinnamon” and “soap,” for example, elicit a response not only from the language-processing areas of our brains, but also those devoted to dealing with smells. (…)

Researchers have discovered that words describing motion also stimulate regions of the brain distinct from language-processing areas. (…)

The brain, it seems, does not make much of a distinction between reading about an experience and encountering it in real life; in each case, the same neurological regions are stimulated. (…) Fiction — with its redolent details, imaginative metaphors and attentive descriptions of people and their actions — offers an especially rich replica. Indeed, in one respect novels go beyond simulating reality to give readers an experience unavailable off the page: the opportunity to enter fully into other people’s thoughts and feelings. (…) Scientists call this capacity of the brain to construct a map of other people’s intentions “theory of mind.” Narratives offer a unique opportunity to engage this capacity, as we identify with characters’ longings and frustrations, guess at their hidden motives and track their encounters with friends and enemies, neighbors and lovers. (…)

Reading great literature, it has long been averred, enlarges and improves us as human beings. Brain science shows this claim is truer than we imagined.

{ NYT | Continue reading }

books, neurosciences, psychology | March 19th, 2012 12:10 pm

University of Alberta study explores women’s experiences of public change rooms and locker rooms; finds many don’t relish the experience of being naked in front of others.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

In recent years, a small number of researchers have been working to develop the science of post-coitus.

{ Salon | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships, sex-oriented | March 16th, 2012 3:52 pm

The memory for odors has been studied mostly from the point of view of odor recognition. In the present work, the memory for odors is studied not from the point of view of recognition but from the hedonic dimension of the sensation aroused by the stimulus.

Hedonicity is how we like or dislike a conscious experience. Hedonicity seems to be especially predominant with olfactory sensation. What will be studied, therefore, is the capacity to remember stimuli as a function of the amount of pleasure or displeasure aroused by the stimuli – in our case, odors. In the following pages, the term “pleasure/displeasure” will be considered as describing the hedonic dimension of consciousness. (…)

The “goodness” of a person’s memory for a given event is known to depend on variables such as the nature of the event, the context within which it occurs, initial encoding and subsequent recoding operations performed on the input, and the extent to which retrieval cues match these operations. It was shown also that slides arousing stronger emotions tended to be better remembered.

The question addressed in the present experiment concerned the role of perceived or felt pleasure or displeasure evoked by the experienced stimulus events. The hypothesis was that the hedonic dimension of cognition, aroused by the events at encoding and stored in memory, plays an important role in remembering of the events.

Pleasure/displeasure and emotion have long been recognized as dominant features in odorant stimulation, description, and memory. EEG recordings demonstrate the deep influence of olfactory stimuli on the brain. “The most important function of the nose may be not in transmitting messages about the outside world, but in motivating the organism after the message has been received” (Engen, 1973); that function being already present in the newborn and even intra utero.

Animal experiments have shown that odors followed by a reward were better remembered than non-rewarded odors, which is a clue that memory privileges usefulness. It was demonstrated also that recollections evoked by odors are more emotional than those evoked verbally, that verbal codes are not necessary for odor-associated memory and finally that pleasant odors enhance approach behavior due to their hedonic dimension. These findings suggest that the sensory stimulus in olfaction should provide a favorable paradigm to test the hypothesis that hedonicity is a potent factor for storing a piece of information into memory.

{ International Journal of Psychological Studies | Continue reading }

olfaction, psychology | March 15th, 2012 7:35 am

images { 1 | 2 }

psychology, relationships | March 14th, 2012 1:13 pm

If you’re looking to enhance your experience of abstract art, you may want to consider spending some pre-gallery time watching a horror film. Kendall Eskine and his colleagues Natalie Kacinik and Jesse Prinz have investigated how different emotions, as well as physiological arousal, influence people’s sublime experiences whilst viewing abstract art. Their finding is that fear, but not happiness or general arousal, makes art seem more sublime.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

art, psychology | March 12th, 2012 3:05 pm

In their 2006 research they compared 40 exotic dancers with a similar number of young adult females who didn’t strip for a living. Using validated surveys, and interviewing both groups, they made some significant findings:

• Strippers had remarkably less satisfaction from their personal relationships and were more likely to think their romantic partnerships would fail

• There was no difference in self-esteem between strippers and non-strippers

• Strippers prized their physical appearance over and above their other qualities and abilities.

• If a stripper felt their body was not beautiful enough, their self-esteem would be affected.

• Strippers seemed to be slightly less satisfied with their body and were more likely to scrutinise their physical appearance. More often they would “be ashamed if people knew what I really weigh”.

{ Dr Stu’s Blog | Continue reading }

psychology | March 12th, 2012 2:39 pm

Getting older makes us happier, because we give up on our dreams

Although physical quality of life goes down after middle age, mental satisfaction increases.

The study of more than 10,000 people in Britain and the US adds support to a previous report that happiness levels form a U-curve, hitting their low point at around 45, then rising.

{ Telegraph | Continue reading }

psychology | March 12th, 2012 2:24 pm

In one experiment, the psychologists asked a group of Christian students to give their impressions of the personalities of two people. In all relevant respects, these two people were very similar – except one was a fellow Christian and the other Jewish. Under normal circumstances, participants showed no inclination to treat the two people differently. But if the students were first reminded of their mortality (e.g., by being asked to fill in a personality test that included questions about their attitude to their own death) then they were much more positive about their fellow Christian and more negative about the Jew.

The researchers behind this work – Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg and Tom Pyszczynski – were testing the hypothesis that most of what we do we do in order to protect us from the terror of death; what they call “Terror Management Theory.” Our sophisticated worldviews, they believe, exist primarily to convince us that we can defeat the Reaper. Therefore when he looms, scythe in hand, we cling all the more firmly to the shield of our beliefs.

This research, now spanning over 400 studies, shows what poets and philosophers have long known: that it is our struggle to defy death that gives shape to our civilization. (…)

The psychologists, psychiatrists and anthropologists who developed Terror Management Theory have shown that almost all ideologies, from patriotism to communism to celebrity culture, function similarly in shielding us from death’s approach. (…)

In one now classic secular example, the researchers recruited court judges from Tucson in the USA. Half of these judges were reminded of their mortality (again with the otherwise innocuous personality test) and half were not. They were then all asked to rule on a hypothetical case of prostitution similar to those they ruled on every day. The judges who had first been reminded of their mortality set a bond (the equivalent of bail) nine times higher than those who hadn’t (averaging $455 compared to $50).

So just like the Christians, they reacted to the thought of death by clinging more fiercely to their worldview.

{ New Humanist | Continue reading }

artwork { Lui Liu }

ideas, psychology | March 7th, 2012 4:14 pm

The most destructive of the defense mechanisms are those that involve being deeply out of touch with reality. (…) A classic example is delusion. (…) Another example is denial, an inability to accept reality, both publicly and privately, a classic example being denial of a drug or alcohol addiction. (…)

Even for the healthiest among us, reality can be a bit too harsh to confront head on, but Level 4 defense mechanisms are considered to be generally functional. Some examples include humor, which is sometimes the best way to cope with emotional pain, and sublimation, which involves transforming unacceptable desires into constructive and socially acceptable forms, such as creating art, embarking on a spiritual path, running a marathon, becoming a dentist…

{ Psych Your Mind | Continue reading }

image { Nam June Paik, 9/23/69: Experiment with David Atwood, 1969 }

psychology | February 29th, 2012 3:14 pm

When people have positive experiences with members of another group, they tend to generalize these experiences from the group member to the group as a whole. This process of member-to-group generalization results in less prejudice against the group. Notably, however, researchers have tended to ignore what happens when people have negative experiences with group members.

In a recent article, my colleagues and I proposed that negative experiences have an opposite but stronger effect on people’s attitudes towards groups.

{ Mark Rubin | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships | February 29th, 2012 3:05 pm

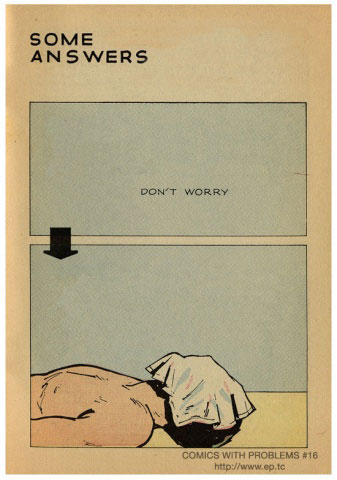

When a person you care about is feeling sad, the standard response in civilized society is to say “everything will be ok” in some shape or form. This decreases the perceived negativity of the situation, and that causes the person to lower their sadness to a level that corresponds to a new, more positive, outlook.

Unfortunately, some new research shows that there are drawbacks to downplaying a situation’s negativity too much. When you attempt to show a situation is not as bad as a person thinks, the implied message is that the person’s level of sadness is beyond what’s socially acceptable. After all, if the person should be this sad, you wouldn’t be telling them to cheer up. It turns out that perceived societal expectations about when a person should be sad play a big role in making negative emotions worse. Specifically, when people feel sad, but think that others don’t expect them to feel sad, their negative emotions are amplified.

{ Peer-reviewed by my neurons | Continue reading }

psychology | February 22nd, 2012 4:20 pm

To explain the pervasive role of humor in human social interaction and among mating partner preferences, Miller proposed that intentional humor evolved as an indicator of intelligence. To test this, we looked at the relationships among rater-judged humor, general intelligence, and the Big Five personality traits in a sample of 185 college-age students (115 women, 70 men).

General intelligence positively predicted rater-judged humor, independent of the Big Five personality traits. Extraversion also predicted rater-judged humor, although to a lesser extent than general intelligence. General intelligence did not interact with the sex of the participant in predicting rating scores on the humor production tasks.

The current study lends support to the prediction that effective humor production acts as an honest indicator of intelligence in humans. In addition, extraversion, and to a lesser extent, openness, may reflect motivational traits that encourage humor production.

{ Evolutionary Psychology | PDF }

haha, psychology, relationships | February 10th, 2012 9:38 am

Do People Know What They Want: A Similar or Complementary Partner?

In the last few decades numerous studies have been carried out on the characteristics individuals value most in a mate. Several studies have, for instance, shown that individuals, especially men, highly value a potential mate’s physical attractiveness.

Much more scarce are studies that relate individuals’ own characteristics to those they desire in a potential mate. With regard to these “relative” mate preferences two hypotheses have been presented.

First, according to the “similarity-attraction hypothesis” individuals feel most attracted to potential partners who, in important domains, are similar to themselves. Similar individuals are assumed to be attractive because they validate our beliefs about the world and ourselves and reduce the risk of conflicts. Not surprisingly therefore, similarity between partners contributes to relationship satisfaction. Because a happy and long-lasting intimate relationship contributes to both psychological and physical health, similarity between partners increases their own and their offspring’s chances of survival by helping maintain (the quality of) the pair bond.

In contrast, according to the “complementarity hypothesis” individuals feel most attracted to potential partners who complement them, an assumption that reflects the saying that “opposites attract.” Complementary individuals are assumed to be so attractive because they enhance the likelihood that one’s needs will be gratified. For example, young women who lack economic resources may feel attracted to older men who have acquired economic resources and therefore may be good providers. In addition, from an evolutionary perspective, one might argue that seeking a complementary mate, rather than a similar one, may help prevent inbreeding.

Studies on mate selection have consistently found support for the “similarity- attraction” hypothesis. Homogamy has been reported for numerous characteristics such as physical attractiveness, attachment style, political and religious attitudes, socio-economic background, level of education and IQ. In contrast, support for the “complementarity hypothesis” is much scarcer. Although many individuals occasionally feel attracted to “opposites,” attractions between opposites often do not develop into serious intimate relationships and, when they do, these relationships often end prematurely.

{ Evolutionary Psychology | PDF }

psychology, relationships | February 8th, 2012 9:27 am

In a recent paper published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, researchers at Arizona State demonstrated that male faces are more likely than female faces to “grab” the anger from an adjacent face, while female faces are more likely to “grab” happiness.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

faces, psychology, relationships | February 7th, 2012 2:28 pm

What does “free time” mean to you? When you’re not at work, do you pass the time — or spend it?

The difference may impact how happy you are. A new study shows people who put a price on their time are more likely to feel impatient when they’re not using it to earn money. And that hurts their ability to derive happiness during leisure activities.

Treating time as money can actually undermine your well-being,” says Sanford DeVoe, one of two researchers at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management who carried out the study.

{ University of Toronto | Continue reading }

photo { Scarlett Hooft Graafland }

economics, leisure, psychology | February 7th, 2012 12:20 pm

Most American bookstores stock a plurality of titles on sex differences. One popular series explains (figuratively) that men are from Mars, women from Venus, and that understanding these differences can demystify and provide behavioral guidelines on a date, in the bedroom, while raising children and, after things fall apart, when starting over following a breakup. Among other things, such popular books reflect and reinforce popular stereotypes that women are more emotional than men, particularly regarding sadness. Scientific evidence, in contrast, makes quite clear that the sexes are more similar than different in emotional experience, suggesting that stereotypes generally overstate emotional sex differences.

The contrast between popular stereotypes about emotional sex differences versus scientific demonstrations of those sex differences naturally raises the question: Why don’t people’s personal emotional experiences dissuade beliefs in stereotypic sex differences? If women and men don’t experience emotions of different intensity, why do they believe that they do? We think that one reason is that stereotypes can influence people’s memory of their own emotions, which consequently reinforce stereotypic sex differences. We hypothesize, specifically, that stereotypes influence memory of emotion such that people recall their own emotions more stereotypically when the relative accessibility of those stereotypes is high. Procedures that increase stereo- types’ relative accessibility, such as cognitive load and priming, should therefore increase stereotypic sex differences in emotion memory.

(…)

The results of three experiments provide evidence that the relative accessibility of stereotypes about sex difference influences people’s memory of very recent emotions.

{ Journal of Experimental Social Psychology | PDF }

photo { Francesco Nazardo }

genders, psychology | February 1st, 2012 2:58 pm

Facebook users can spread emotions to their online connections just by posting a written message, or status update, that’s positive or negative, says a psychologist who works for the wildly successful social network.

This finding challenges the idea that emotions get passed from one person to another via vocal cues, such as rising or falling tone, or by a listener unconsciously imitating a talker’s body language, said Adam Kramer on January 27 at the annual meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology. Kramer works at Facebook’s headquarters in Palo Alto, Calif.

“It’s time to rethink how emotional contagion works, since vocal cues and mimicry aren’t needed,” Kramer said. “Facebook users’ emotion leaks into the emotional worlds of their friends.”

{ ScienceNews | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships, social networks | January 31st, 2012 12:27 pm

In fact, it has become pretty clear that deciphering consciousness will definitely be more difficult than describing the dynamics of DNA. Crick himself spent more than two decades attempting to unravel the consciousness riddle, working on it doggedly until his death in 2004. His collaborator, neuroscientist Christof Koch of Caltech, continues their work even today, just as dozens of other scientists pursue a similar agenda — to identify the biological processes that constitute consciousness and to explain how and why those processes produce the subjective sense of persistent identity, the self-awareness and unity of experience, and the “awareness of self-awareness” that scientists and philosophers have long wondered about, debated and sometimes even claimed to explain.

So far, no one has succeeded to anyone else’s satisfaction. Yes, there have been advances: Understanding how the brain processes information. Locating, within various parts of the brain, the neural activity that accompanies certain conscious perceptions. Appreciating the fine distinctions between awareness, attention and subjective impressions. But yet with all this progress, the consciousness problem remains popular on lists of problems that might never be solved.

Perhaps that’s because the consciousness problem is inherently similar to another famous problem that actually has been proved unsolvable: finding a self-consistent set of axioms for deducing all of mathematics. As the Austrian logician Kurt Gödel proved eight decades ago, no such axiomatic system is possible; any system as complicated as arithmetic contains true statements that cannot be proved within the system.

Gödel’s proof emerged from deep insights into the self-referential nature of mathematical statements. He showed how a system referring to itself creates paradoxes that cannot be logically resolved — and so certain questions cannot in principle be answered.

{ ScienceNews | Continue reading }

photo { Kim Boske }

ideas, neurosciences, psychology | January 30th, 2012 8:12 am