psychology

It seems hard to imagine that anyone of sound mind would take the blame for something he did not do. But several researchers have found it surprisingly easy to make people fess up to invented misdemeanours. Admittedly these confessions are taking place in a laboratory rather than an interrogation room, so the stakes might not appear that high to the confessor. On the other hand, the pressures that can be brought to bear in a police station are much stronger than those in a lab. The upshot is that it seems worryingly simple to extract a false confession from someone—which he might find hard subsequently to retract.

{ The Economist | Continue reading }

psychology | August 15th, 2011 2:25 pm

Having pain that persists creates a lot of stress, but there are many people who can limit the effect on their life and carry on. These people seem to return to their everyday activities even if their pain hasn’t settled. Then there are the other people. This group have much more trouble managing with their pain. They have more disability, more distress, seek more treatments and the impact of their pain spreads from the direct effect on their life, to effects on people around them.

If we could identify, then treat the risk factors that can lead to trouble recovering from pain, we might be able to limit the long term effects that chronic pain can have on people and our community. While maybe 25 years ago the factors were thought to be biomechanical, or things like the extent of tissue damage – and yes, these do have some effect – over time it has become clear that psychosocial factors play an important role. (…)

Catastrophising has been identified as a risk factor for greater disability and distress. Catastrophising is the tendency to “think the worst” and has been viewed as an independent risk factor for longterm disability for some time.

{ HealthSkills | Continue reading }

psychology | August 10th, 2011 10:05 am

What could be wrong with a gentleman opening a door for a lady? According to some social psychologists, such acts endorse gender stereotypes: the idea that women are weak and need help; that men are powerful patriarchs. Now a study has looked at how women are perceived when they accept or reject an act of so-called “benevolent sexism”* and it finds that they’re caught in a double-bind. Women who accept help from a man are seen as warmer, but less competent. Women who reject help are seen as more competent, but cold.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

genders, psychology, relationships | August 10th, 2011 10:00 am

Turns out that your name is more influential than you think.

Researchers found that the “speed with which adults acquire items [correlates] to the first letter of their childhood surname.”

This means that when it comes to purchasing goods, people with last names that begin with a letter closer to the end of the alphabet tend to acquire items faster than people with last names that begin with a letter closer to the beginning of the alphabet. They call it the “Last Name Effect,” and hypothesize that it is caused by “childhood ordering structure.”

In their words, “since those late in the alphabet are typically at the end of lines, they compensate by responding quickly to acquisition opportunities.”

{ Why We Reason | Continue reading }

photo { Louis Stettner, Rue des Martyrs, 1951 }

Onomastics, economics, psychology | August 4th, 2011 4:05 pm

“The typical view is that women take less risks than men, that it starts early in childhood, in all cultures, and so on,” says Bernd Figner of Columbia University and the University of Amsterdam. The truth is more complicated. Men are willing to take more risks in finances. But women take more social risks—a category that includes things like starting a new career in your mid-thirties or speaking your mind about an unpopular issue in a meeting at work.

It seems that this difference is because men and women perceive risks differently. That difference in perception may be partly because of how familiar they are with different situations, Figner says. “If you have more experience with a risky situation, you may perceive it as less risky.” Differences in how boys and girls encounter the world as they’re growing up may make them more comfortable with different kinds of risks.

Adolescents are known for risky behavior. But in lab tests, when they’re called on to think coolly about a situation, psychological scientists have found that adolescents are just as cautious as adults and children.

{ APS | Continue reading }

artwork { Fra Filippo Lippi, Portrait of a Woman with a Man at a Casement, ca. 1440–44 }

genders, psychology | July 29th, 2011 8:41 pm

The benefits of body-language mimicry have been confirmed by numerous psychological studies. And in popular culture, mirroring is frequently urged on people as a strategy – for flirting or having a successful date, for closing a sale or acing a job interview. But new research suggests that mirroring may not always lead to positive social outcomes. In fact, sometimes the smarter thing to do is to refrain. (…)

Interviewees who mimicked the unfriendly interlocutor were judged to be less competent than those who didn’t.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships | July 29th, 2011 8:30 pm

Economists have long argued that individuals, particularly those in the lower socioeconomic stratum, engage in conspicuous consumption to signal their status in society. Since one’s income, a common marker of status, is not visible to others, individuals can speciously signal their wealth by displaying products that are a surrogate for income, such as luxury watches, expensive cars, and designer clothes. Alternatively, a psychological perspective on this phenomenon suggests that status consumption is driven by a desire to restore various forms of self-worth. For instance, aversive psychological states such as powerlessness and self-threat drive individuals to consume status goods for their compensatory benefits.

We contend that this desire to protect and restore one’s self-worth affects not only what is consumed but also how it is consumed—purchased through credit versus cash. Specifically, the very same psychological force (i.e., threatened self- worth) that compels individuals toward status consumption may also increase individuals’ likelihood of consuming these goods through credit rather than cash.

{ SAGE | Continue reading }

painting { Alex Gross }

economics, psychology | July 29th, 2011 8:17 pm

In a study published in 2009, evolutionary theory advocates forwarded the notion that depression could be seen as an evolutionary trait, developed to solve complex problems.

The logics behind this hypothesis was that rumination, a salient trait of depression, allowed for a kind of concentration on one single problem that was absolutely necessary to solve certain complex issues.

{ BrainBlogger | Continue reading }

related { A diagnosis of insomnia relies on the way the following questions are answered, “Do you experience difficulty sleeping?” or “Do you have difficulty falling or staying asleep?” You answer yes to either of those and you have insomnia.

psychology | July 29th, 2011 6:33 pm

Simply speaking, disgust is the response we have to things we find repulsive. Some of the things that trigger disgust are innate, like the smell of sewage on a hot summer day. No one has to teach you to feel disgusted by garbage, you just are. Other things that are automatically disgusting are rotting food and visible cues of infection or illness. We have this base layer of core disgusting things, and a lot of them don’t seem like they’re learned.

But there’s also a whole set of things that have a lot of cultural and individual variation about whether it’s considered disgusting. For example, I like bloody steaks and my girlfriend, who is a vegetarian, finds them repulsive. The core base of what causes disgust has expanded to the point where certain kinds of moral violations, social transgressions, and even value systems of groups one is not a member of can come to be disgusting as well.

There’s a good case to be made that the culture we grow up in can fine-tune our disgust response or calibrate what we come to be disgusted by, but people don’t really need to learn how to be disgusted. The reaction is specified by nature, although it doesn’t start until we are around 3 or 4 years old.

{ Daniel Kelly/Salon | Continue reading }

gross, psychology, science | July 28th, 2011 6:50 pm

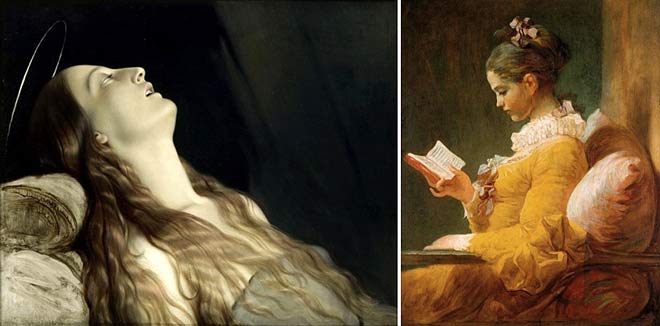

Scientists at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have found that when just 10 percent of the population holds an unshakable belief, their belief will always be adopted by the majority of the society. The scientists, who are members of the Social Cognitive Networks Academic Research Center (SCNARC) at Rensselaer, used computational and analytical methods to discover the tipping point where a minority belief becomes the majority opinion. (…)

The percentage of committed opinion holders required to influence a society remains at approximately 10 percent, regardless of how or where that opinion starts and spreads in the society.

{ ScienceBlog | Continue reading }

paintings { 1. Hippolyte Delaroche, Louise Vernet, Wife of the Artist, on Her Deathbed, 1845 | 2. Fragonard, The Reader, ca.1770-72 }

ideas, psychology | July 27th, 2011 6:06 pm

In January of 2007, the Washington Post asked world-renown violinist Joshua Bell to perform the 43-minute piece Bach piece “Sonatas and Partitas for Unaccompanied Violin,” in the L’Enfant Plaza subway station – one of D.C.’s busiest subway stations – during the heart of rush hour.

Joshua Bell was used to performing in front of sold out crowds, filled with ambassadors and state leaders, in the finest concert halls across the globe. He is generally considered one of the best violinists alive, and his talents pay him substantial dividends.

However, as over a thousand morning commuters passed by Joshua Bell on that cold morning in January, his credentials were humbly irrelevant. To everyone’s surprise, The Post found that, “of the 1,097 people who walked by, hardly anyone stopped. One man listened for a few minutes, a couple of kids stared, and one woman, who happened to recognize the violinist, gaped in disbelief.” Many were expecting Joshua Bell to cause music pandemonium with his free subway appearance, but his performance garnered no more attention than any other street musician.

Gene Weingarten, the author of the piece, went on to win a Pulitzer prize, but psychologists and laypeople alike were left asking the same question: why didn’t people stop and listen?

{ Why We Reason | Continue reading }

music, psychology | July 25th, 2011 9:07 am

Human interactions often provide people with considerable social support, but can pets also fulfill one’s social needs? Although there is correlational evidence that pets may help individuals facing significant life stressors, little is known about the well-being benefits of pets for everyday people.

Study 1 found in a community sample that pet owners fared better on several well-being (e.g., greater self-esteem, more exercise) and individual-difference (e.g., greater conscientiousness, less fearful attachment) measures.

Study 2 assessed a different community sample and found that owners enjoyed better well-being when their pets fulfilled social needs better, and the support that pets provided complemented rather than competed with human sources.

Finally, Study 3 brought pet owners into the laboratory and experimentally demonstrated the ability of pets to stave off negativity caused by social rejection.

In summary, pets can serve as important sources of social support, providing many positive psychological and physical benefits for their owners.

{ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology | PDF }

photo { Andre Kertesz, Study of People and Shadows, 1928 | more photos }

animals, cats, dogs, psychology, relationships | July 22nd, 2011 4:20 pm

Traditionally, nostalgia has been conceptualized as a medical disease and a psychiatric disorder. Instead, we argue that nostalgia is a predominantly positive, self-relevant, and social emotion serving key psychological functions. Nostalgic narratives reflect more positive than negative affect, feature the self as the protagonist, and are embedded in a social context. Nostalgia is triggered by dysphoric states such as negative mood and loneliness. Finally, nostalgia generates positive affect, increases self-esteem, fosters social connectedness, and alleviates existential threat.

{ IngentaConnect }

ideas, psychology | July 20th, 2011 8:00 pm

The next time you feel angry at a friend who has let you down, or grateful toward one whose generosity has surprised you, consider this: you may really be bargaining for better treatment from that person in the future. According to a controversial new theory, our emotions have evolved as tools to manipulate others into cooperating with us.

Until now, most psychologists have viewed anger as a way to signal your displeasure when another person does you harm. Similarly, gratitude has been seen as a signal of pleasure when someone does you a favour. In both cases, emotions are seen as short-term reactions to an immediate benefit or cost.

But it’s more cunning than that, says John Tooby, an evolutionary psychologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Anger, he says, has as much to do with cooperation as with conflict, and emotions are used to coerce others into cooperating in the long term. (…)

All this suggests that anger and gratitude – and perhaps other emotions, too – may be tools for turning up a partner’s mental cooperation control dial.

{ NewScientist | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships | July 19th, 2011 9:26 pm

Let’s try something for a second: Why don’t you think back on the story of your life. While you are thinking back, try to remember why you got to the job you did, the city you now live in, the neighborhood, the relationships, etc. Most likely you–and most people for that matter–took a long winding road to where you are now. It’s also likely that you can pinpoint a few critical decisions you made in the past that have really shaped who you are today, and what you did to get here.

We often construct these life narratives. (…) How true are these narratives really? Do we really know the two or three critical points in our lives that changed everything and made us the people we are today? Psychological science says no. (…)

Nisbett and Wilson concluded, based on this research, that we have strong motivations for prediction and control of our social environments. That is, we’re thinking creatures who want to know how stuff works, and as such, we are constantly constructing theories that could plausibly explain what is happening in our environments. The reality though is that these theories are never really tested or confirmed, and so they are often fabrications–based on our own beliefs about how the world works rather than on how the world actually works (which may be more chaotic than we’d like to admit).

{ Psych Your Mind | Continue reading }

psychology | July 19th, 2011 8:13 pm

Researchers have shown that we sit near people who look like us.

The effect is more than just people of the same sex or ethnicity tending to aggregate — a phenomenon well documented by earlier research.

The new finding could help explain why it is that people so often resemble physically their friends and romantic partners (known as “homophily”) — if physically similar people choose to sit near each other, they will have more opportunities to forge friendships and romances. (…)

A further possibility is that seeking proximity to physically similar others is an evolutionary hang-over — an instinct for staying close to genetically similar kin.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships | July 18th, 2011 5:45 pm

“Everything we do involves making choices, even if we don’t think very much about it. For example, just moving your leg to walk in one direction or another is a choice – however, you might not appreciate that you are choosing this action, unless someone were to stop you from moving that leg. We often take for granted all of the choices we make, until they are taken away,” says Mauricio Delgado at Rutgers University.

{ APS | Continue reading }

psychology | July 18th, 2011 5:30 pm

The Misconception: When your beliefs are challenged with facts, you alter your opinions and incorporate the new information into your thinking.

The Truth: When your deepest convictions are challenged by contradictory evidence, your beliefs get stronger.

{ You are not so smart | Continue reading }

photo { Robert Frank }

ideas, psychology | July 15th, 2011 2:49 pm

You probably already know whether you’re a morning or evening person, but if you’re not sure, here are two ways to figure it out:

1) On weekends, or when you don’t have to wake up at any particular time, when do you naturally wake up? If the answer is more than an hour or so different from when you wake up on weekdays, chances are you’re an evening person by nature. Morning people tend to wake up just as early on weekends as they do during the week.

2) Regardless of how much sleep you’ve gotten, when do you find that you have the most energy? If your energy peaks in the morning and dwindles by late afternoon, you’re a morning person. If it peaks later in the evening - you guessed it - you’re an evening person. (…)

The debate over whether it’s better to be a night owl or an early bird has been going on for centuries. (…) Research on the advantages and disadvantages of each “chronotype” has yielded mixed results, in part because it is difficult to conduct this research experimentally. (…)

Evolutionary psychologists have suggested that a preference for late hours may suggest a higher level of intelligence because being a night owl is presumably an evolutionary novel preference, though this hypothesis is controversial.

{ Psych Your Mind | Continue reading }

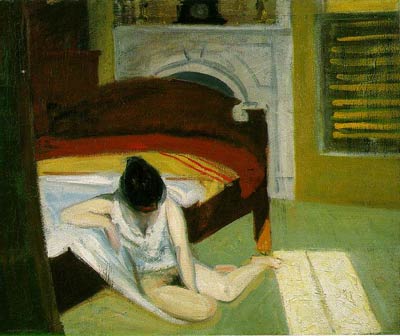

painting { Edward Hopper, Summer Interior, 1909 }

guide, psychology, sleep | July 15th, 2011 12:38 am

In the late 1990s, Jane Anderson was working as a landscape architect. That meant she didn’t work much in the winter, and she struggled with seasonal affective disorder in the dreary Minnesota winter months. She decided to try meditation and noticed a change within a month. “My experience was a sense of calmness, of better ability to regulate my emotions,” she says. Her experience inspired a new study which will be published in an upcoming issue of Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, which finds changes in brain activity after only five weeks of meditation training.

Previous studies have found that Buddhist monks, who have spent tens of thousands of hours of meditating, have different patterns of brain activity. But Anderson wanted to know if they could see a change in brain activity after a shorter period.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading | Related: Meditation as cheap, self-administered morphine }

Why does exercise make us happy and calm? (…) How, at a deep, cellular level, exercise affects anxiety and other moods has been difficult to pin down. The brain is physically inaccessible and dauntingly complex. But a recent animal study from researchers at the National Institute of Mental Health provides some intriguing new clues into how exercise intertwines with emotions, along with the soothing message that it may not require much physical activity to provide lasting emotional resilience.

{ NYT | Continue reading }

photo { T. Harrison Hillman }

guide, health, neurosciences, photogs, psychology | July 11th, 2011 5:21 pm