“After they arrested me, I sat in my cell and I thought, ‘I’m looking at five to seven years.’ So I asked the other prisoners what to do. They said, ‘Easy! Tell them you’re mad! They’ll put you in a county hospital. You’ll have Sky TV and a PlayStation. Nurses will bring you pizzas.’”

“How long ago was this?” I asked.

“Twelve years ago,” Tony said.

Tony said faking madness was the easy part, especially when you’re 17 and you take drugs and watch a lot of scary movies. You don’t need to know how authentically crazy people behave. You just plagiarise the character Dennis Hopper played in the movie Blue Velvet. That’s what Tony did. He told a visiting psychiatrist he liked sending people love letters straight from his heart, and a love letter was a bullet from a gun, and if you received a love letter from him, you’d go straight to hell.

Plagiarising a well-known movie was a gamble, he said, but it paid off. Lots more psychiatrists began visiting his cell. He broadened his repertoire to include bits from Hellraiser, A Clockwork Orange and David Cronenberg’s Crash. Tony told the psychiatrists he liked to crash cars into walls for sexual pleasure and also that he wanted to kill women because he thought looking into their eyes as they died would make him feel normal. (…)

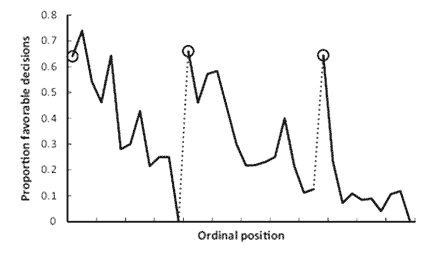

Tony said the day he arrived at the dangerous and severe personality disorder (DSPD) unit, he took one look at the place and realised he’d made a spectacularly bad decision. He asked to speak urgently to psychiatrists. “I’m not mentally ill,” he told them. It is an awful lot harder, Tony told me, to convince people you’re sane than it is to convince them you’re crazy. (…)

“I know people are looking out for ‘nonverbal clues’ to my mental state,” Tony continued. “Psychiatrists love ‘nonverbal clues’. They love to analyse body movements. But that’s really hard for the person who is trying to act sane. How do you sit in a sane way? How do you cross your legs in a sane way?” (…) “I volunteered to weed the hospital garden. But they saw how well behaved I was and decided it meant I could behave well only in the environment of a psychiatric hospital and it proved I was mad.” (…)

I didn’t know what to think. Unlike the sad-eyed, medicated patients all around us, Tony had seemed perfectly ordinary and sane. But what did I know?

The next day I wrote to Professor Anthony Maden, the head clinician at Tony’s unit at Broadmoor – “I’m contacting you in the hope that you may be able to shed some light on how true Tony’s story might be.” (…)

A week passed and then the email I had been waiting for arrived from Professor Maden. “Tony,” it read, “did get here by faking mental illness because he thought it would be preferable to prison.” (…)

“Most psychiatrists who have assessed him, and there have been a lot, have considered he is not mentally ill, but suffers from psychopathy.” (…)

Faking mental illness to get out of a prison sentence, Maden explained, is exactly the kind of deceitful and manipulative act you’d expect of a psychopath.

{ Guardian | Continue reading }