psychology

Verb tense is more important than you may think, especially in how you form or perceive intention in a narrative.

In recent research studied in Psychological Science, William Hart of the University of Alabama states that “when you describe somebody’s actions in terms of what they’re ‘doing,’ that action is way more vivid in [a reader’s] mind.” Subsequently, when action is imagined vividly, greater intention is associated with it. (…)

Those who read that the defendant “was firing gun shots” believed a more harmful intent of the defendant than those who read that he “fired gun shots”.

{ APS | Continue reading }

screenshot { Cowboys and Aliens, 2011 }

Linguistics, psychology | March 14th, 2011 5:05 pm

That sex reduces stress –- or that no sex increases stress –- is hardly a new observation. A team of German researchers, though, is arguing that sexual frustration is a complex phenomenon not to be underestimated. It can precipitate a downward spiral, pulling couples helplessly and unbeknownst into a swirling vortex of all work and no nookie.

Ragnar Beer of the University of Göttingen surveyed almost 32,000 men and women for his Theratalk Project (2007), which has found that the less sex you have, the more work you seek. Indeed, the sexually deprived have to find outlets for their frustrations: they often take on more commitments and work.

{ Der Spiegel | Continue reading }

photo { Helmut Newton }

psychology, sex-oriented | March 13th, 2011 6:38 pm

The brain may manage anger differently depending on whether we’re lying down or sitting up, according to a study published in Psychological Science that may also have worrying implications for how we are trying to understand brain function. (…)

A field of study called ‘embodied cognition‘ has found lots of curious interactions between how the mind and brain manage our responses depending on the possibilities for action.

For example, we perceive distances as shorter when we have a tool in our hand and intend to use it, and wearing a heavy backpack causes hills to appear steeper.

{ Mind Hacks | Continue reading }

brain, psychology, relationships | March 10th, 2011 5:48 pm

A psych study asked people to think of someone they felt guilty toward, or made them imagine feeling guilty toward someone (e.g., slacking off on a joint project, or being careless with something borrowed). Researchers then had these guilty folks divide up money between themselves, the victim, and a third party (e.g., a deserving charity or random person). Compared to controlled conditions, such people give more money to the victim, but at the expense of the third party, not themselves.

{ OvercomingBias | Continue reading }

collage { Mark Wagner }

psychology, relationships | March 8th, 2011 7:00 pm

In January, the shooting of Gabrielle Giffords produced a half dozen bona fide heroes, including Patricia Maisch, a 61-year-old woman who snatched ammunition out of alleged gunman Jared Loughner’s hands as he tried to reload. For good reason, people like these earn our respect and adulation; their grace under pressure strikes us as almost superhuman. Yet as we marvel at their deeds, we’re always left wondering about where, exactly, this composure comes from. Do these people emerge from the womb with sanguine looks on their faces, ready to perform life-saving surgery in the next room if necessary? Or is their coolness something they picked up through life experience? (…)

Let’s start with the “nature” side of the equation. For every one of us, the starting point for cool-headedness comes bundled within our DNA: our innate disposition toward anxiety. It’s never been a secret that anxiousness is partially inherited, but no one knew how much influence our genes threw around until psychiatrist Kenneth Kendler came along. In a 2001 study, Kendler and his colleagues examined 1,200 pairs of male twins, some identical and some fraternal, probing into each brother’s individual phobias. Because all of the twins shared the same upbringing, yet only the identical twins shared the same DNA, Kendler could filter out environmental factors altogether and calculate a pure figure for our genetic susceptibility to anxiety. The answer? Genes account for around 30 percent of our anxiousness.

{ Slate | Continue reading }

genes, psychology, science | March 7th, 2011 6:50 pm

We modify our own opinions in line with what other people think, especially our friends and peers.

A problem for psychologists investigating the effect of peer influence is that it can be tricky to tell whether people are simply acquiescing in public, for show, or if their attitudes really have changed.

A new study by a team of psychologists at Harvard University has used an innovative mix of behavioural and brain-scan methods to show that peer influence really can change how people value something, in this case the attractiveness of a face.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

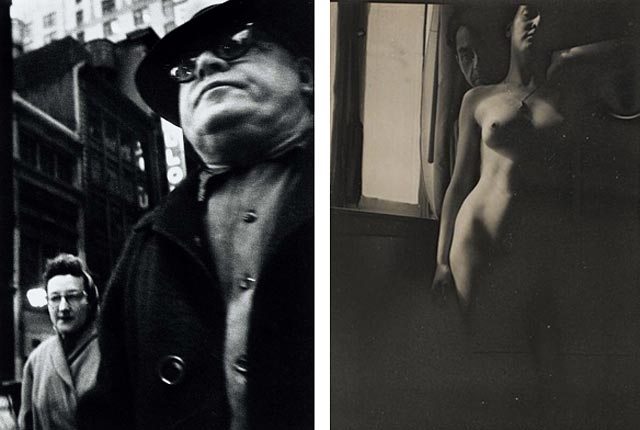

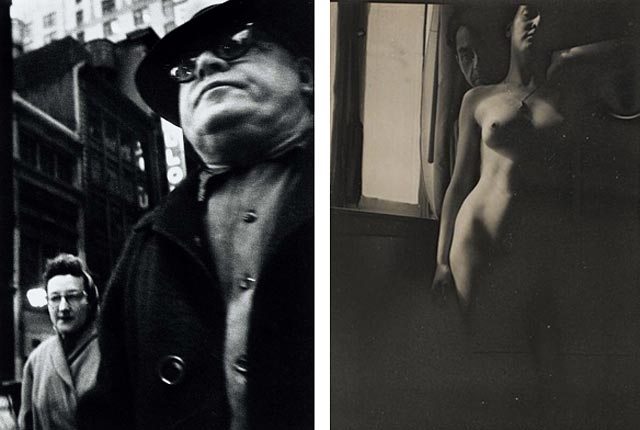

photos { William Klein, Man Foreground, Woman Behind, 1955 | Right: Man Ray, Self-Portrait with Meret Oppenheim, 1933 }

halves-pairs, photogs, psychology, relationships | March 7th, 2011 6:25 pm

People with full bladders make better decisions.

Researchers discovered the brain’s self-control mechanism provides restraint in all areas at once. They found people with a full bladder were able to better control and “hold off” making important, or expensive, decisions, leading to better judgement. (…)

Dr Mirjam Tuk, who led the study, said that the brain’s “control signals” were not task specific but result in an “unintentional increase” in control over other tasks.

“People are more able to control their impulses for short term pleasures and choose more often an option which is more beneficial in the long run,” she said. (…)

They concluded that people with full bladders were better at holding out for the larger rewards later.

{ Telegraph | Continue reading | Thanks Tim! }

psychology, water | March 3rd, 2011 2:10 pm

New findings provide further evidence that abstract concepts are grounded in sensory metaphors. Just as holding a heavy object makes us perceive an issue as being more important, and physical warmth makes us perceive an interpersonal relationship as also being warm, so does touching something tough or tender influence our mental representation of social categories such as sex.

{ Neurophilosophy | Continue reading }

photo { Jill Freedman }

psychology, relationships | March 2nd, 2011 7:20 pm

Researchers looked at whether simple restoration of justice (“an eye for an eye”) is enough for us or if we also want the offender to understand just what they did wrong. (…)

They concluded that simple equalization of suffering is not enough—we also want the offender to know just why they were punished (for their bad or mean-spirited behavior).

{ Keene Trial Consulting | Continue reading }

psychology | March 2nd, 2011 7:10 pm

It’s about Professor Daryl Bem and his cheerful case for ESP.

According to “Feeling the Future,” a peer-reviewed paper the APA’s Journal of Personality and Social Psychology will publish this month, Bem has found evidence supporting the existence of precognition. (…)

Responses to Bem’s paper by the scientific community have ranged from arch disdain to frothing rejection. And in a rebuttal—which, uncommonly, is being published in the same issue of JPSP as Bem’s article—another scientist suggests that not only is this study seriously flawed, but it also foregrounds a crisis in psychology itself. (…)

Over seven years, Bem measured what he considers statistically significant results in eight of his nine studies. In the experiment I tried, the average hit rate among 100 Cornell undergraduates for erotic photos was 53.1 percent. (Neutral photos showed no effect.) That doesn’t seem like much, but as Bem points out, it’s about the same as the house’s advantage in roulette. (…)

“It shouldn’t be difficult to do one proper experiment and not nine crappy experiments,” the University of Amsterdam’s Eric-Jan Wagenmakers, co-author of the rebuttal, says. (…)

Before PSI, Bem made his biggest splash in the nonacademic world with a politically incorrect but weirdly compelling theory of sexual orientation. In 1996, he published “Exotic Becomes Erotic” in Psychological Review, arguing that neither gays nor straights are “born that way”—they’re born a certain way, and that’s what eventually determines their sexual preference.

“I think what the genes code for is not sexual orientation but rather a type of personality,” he explains. According to the EBE theory, if your genes make you a traditionally “male” little boy, a lover of sports and sticks, you’ll fit in with other boys, so what will be exotic to you—and, eventually, erotic—are females. On the other hand, if you’re sensitive, flamboyant, performative, you’ll be alienated from other boys, so you’ll gravitate sexually toward your exotic—males.

EBE is not exactly universally accepted.

{ NY mag | Continue reading }

photos { Irina Werning, Back to the future, Mechi 1990 & 2010, Buenos Aires | more }

controversy, mystery and paranormal, psychology | March 2nd, 2011 7:09 pm

A review of more than 160 studies of human and animal subjects has found “clear and compelling evidence” that – all else being equal – happy people tend to live longer and experience better health than their unhappy peers.

{ News Bureau | Continue reading }

photo { Richard Avedon, Veruschka, New York, 1972 }

psychology, science | March 1st, 2011 8:22 pm

Not only do insincere apologies fail to make amends, they can also cause damage by making us feel angry and distrustful towards those who are trying to trick us into forgiving them.

Even sincere apologies are just the start of the repair process. Although we expect the words “I’m sorry” to do the trick, they don’t do nearly as much as we expect.

{ PsyBlog | Continue reading }

photo { Richard Misrach }

psychology, relationships, shit talkers | March 1st, 2011 8:08 pm

We usually think of emotions as conveyed through facial expressions and body language. Science too has focused on these forms of emotional communication, finding that there’s a high degree of consistency across cultures. It’s only in the last few years that psychologists have looked at whether and how the emotions can be communicated purely through touch.

A 2006 study by Matthew Hertenstein demonstrated that strangers could accurately communicate the ‘universal’ emotions of anger, fear, disgust, love, gratitude, and sympathy, purely through touches to the forearm, but not the ‘prosocial’ emotions of surprise, happiness and sadness, nor the ’self-focused’ emotions of embarrassment, envy and pride.

Now Erin Thompson and James Hampton have added to this nascent literature by comparing the accuracy of touch-based emotional communication between strangers and between those who are romantically involved. (…)

The key finding is that although strangers performed well for most emotions, romantic couples tended to be superior, especially for the self-focused emotions of embarrassment, envy and pride.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

images { The Thomas Crown Affair, 1968, directed by Norman Jewison }

psychology, relationships, science | February 26th, 2011 7:27 pm

The 21-year-old woman was carefully trained not to flirt with anyone who came into the laboratory over the course of several months. She kept eye contact and conversation to a minimum. She never used makeup or perfume, kept her hair in a simple ponytail, and always wore jeans and a plain T-shirt.

Each of the young men thought she was simply a fellow student at Florida State University participating in the experiment, which ostensibly consisted of her and the man assembling a puzzle of Lego blocks. But the real experiment came later, when each man rated her attractiveness. Previous research had shown that a woman at the fertile stage of her menstrual cycle seems more attractive, and that same effect was observed here — but only when this woman was rated by a man who wasn’t already involved with someone else.

The other guys, the ones in romantic relationships, rated her as significantly less attractive when she was at the peak stage of fertility, presumably because at some level they sensed she then posed the greatest threat to their long-term relationships. To avoid being enticed to stray, they apparently told themselves she wasn’t all that hot anyway.

This experiment was part of a new trend in evolutionary psychology to study “relationship maintenance.”

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships | February 22nd, 2011 4:24 pm

What can waiters, the TV series ‘Lost’ and the novelist Charles Dickens teach us about avoiding procrastination?

One of the simplest methods for beating procrastination in almost any task was inspired by busy waiters.

It’s called the Zeigarnik effect after a Russian psychologist, Bluma Zeigarnik, who noticed an odd thing while sitting in a restaurant in Vienna. The waiters seemed only to remember orders which were in the process of being served. When completed, the orders evaporated from their memory.

Zeigarnik went back to the lab to test out a theory about what was going on. She asked participants to do twenty or so simple little tasks in the lab, like solving puzzles and stringing beads (Zeigarnik, 1927). Except some of the time they were interrupted half way through the task. Afterwards she asked them which activities they remembered doing. People were about twice as likely to remember the tasks during which they’d been interrupted than those they completed.

What does this have to do with procrastination? (…)

When people manage to start something they’re more inclined to finish it. Procrastination bites worst when we’re faced with a large task that we’re trying to avoid starting. It might be because we don’t know how to start or even where to start.

What the Zeigarnik effect teaches is that one weapon for beating procrastination is starting somewhere…anywhere.

Don’t start with the hardest bit, try something easy first.

{ PsyBlog | Continue reading }

guide, psychology | February 18th, 2011 5:03 pm

Imagine that someone committed a murder. Now imagine that the murderer risked his own life to save another person. Would you forgive the murderer for his crime?

No?

So, how many lives would the murderer need to save to balance out his original sin?

5?

10?

In one study, the median answer was 25.

This is an example of what psychologists call the negativity bias, which is a powerful part of the human mind.

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

images { 1 | 2 }

psychology, science, uh oh | February 15th, 2011 9:27 pm

Cognition researchers should beware assuming that people’s mental faculties have finished maturing when they reach adulthood. So say Laura Germine and colleagues, whose new study shows that face learning ability continues to improve until people reach their early thirties.

Although vocabulary and other forms of acquired knowledge grow throughout the life course, it’s generally accepted that the speed and efficiency of the cognitive faculties peaks in the early twenties before starting a steady decline. This study challenges that assumption.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

painting { Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas (Spanish for “The Maids of Honour”), 1656 | Las Meninas has long been recognised as one of the most important paintings in Western art history. Foucault viewed the painting without regard to the subject matter, nor to the artist’s biography, technical ability, sources and influences, social context, or relationship with his patrons. Instead he analyses its conscious artifice, highlighting the complex network of visual relationships between painter, subject-model, and viewer. For Foucault, Las Meninas contains the first signs of a new episteme, or way of thinking, in European art. It represents a mid-point between what he sees as the two “great discontinuities” in art history. | Wikipedia }

art, ideas, michel foucault, psychology, science | February 15th, 2011 9:20 pm

Women tend to be better than men at reading other people’s subtle facial cues, especially cues from the eyes. Because of the gender difference in cognitive empathy – the ability to notice and correctly interpret body language – psychobiologists have hypothesized that testosterone levels could play a role in “mind reading” ability, or lack thereof.

A new study in PNAS validates this hypothesis by demonstrating that a dose of testosterone can make women lose some of their cognitive empathy.

{ ICHS | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships, science | February 10th, 2011 7:30 pm

Feelings of anxiety are normal and even desirable – they are part of what helps us survive in a world of real threats. But no less crucial is the return to normal – the slowing of the heartbeat and relaxation of tension – after the threat has passed. People who have a hard time “turning off” their stress response are candidates for post-traumatic stress syndrome, as well as anorexia, anxiety disorders and depression.

How does the body recover from responding to shock or acute stress? This question is at the heart of research conducted by Dr. Alon Chen of the Institute’s Neurobiology Department.

The response to stress begins in the brain, and Chen concentrates on a family of proteins that play a prominent role in regulating this mechanism. One protein in the family – CRF – is known to initiate a chain of events that occurs when we cope with pressure, and scientists have hypothesized that other members of the family are involved in shutting down that chain.

In research that appeared in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Chen and his team have now, for the first time, provided sound evidence that three family members known as urocortin 1, 2 and 3 – are responsible for turning off the stress response.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

arwtork { Lucian Freud, Reflection with Two Children (Self-Portrait), 1965 | Freud painted this self-portrait by looking down at his reflection in a mirror placed by his feet; this accounts for the extreme foreshortening, and the halo-like ceiling light just above his left shoulder. The two children are Freud’s daughter and son, Rose and Ali Boyt. Freud said he used a palette knife to describe the space around him, smearing it on and smoothing its surface so that it seems like a strange, grey, voluminous void. | Tate }

brain, psychology, science | February 8th, 2011 9:44 pm

Can you take away the feelings of guilt through self harm? Well, here’s one way to find out.

Take 59 Australian students, and split them into three groups. Get two groups to write about something they did that they feel guilty about.

Then get one of those groups to stick their arms into iced water. The other group gets nice warm water. The third group writes about just some everyday interaction, but then they get the ice bath too.

When Brock Bastian, of the University of Queensland, and colleagues did that they found a couple of things. First the students who wrote about about a guilt-ridden experience really did feel more guilty.

Second, these guilt-ridden students kept their arms in the ice bath longer than the guilt-free students. What’s more, their level of guilt dropped more than the guilt-ridden students who had a warm water bath.

{ Epiphenom | Continue reading }

photo { Nikola Tamindzic }

related { Can one have pain and not know it? }

psychology | February 8th, 2011 8:40 pm