psychology

The idea that an individual has power over his health has a long history in American popular culture. The “mind cure” movements of the 1800s were based on the premise that we can control our well-being. In the middle of that century, Phineas Quimby, a philosopher and healer, popularized the view that illness was the product of mistaken beliefs, that it was possible to cure yourself by correcting your thoughts. Fifty years later, the New Thought movement, which the psychologist and philosopher William James called “the religion of the healthy minded,” expressed a very similar view: by focusing on positive thoughts and avoiding negative ones, people could banish illness.

The idea that people can control their own health has persisted through Norman Vincent Peale’s “Power of Positive Thinking,” in 1952, to a popular book today, “The Secret,” by Rhonda Byrne, which teaches that to achieve good health all we have to do is to direct our requests to the universe.

It’s true that in some respects we do have control over our health. By exercising, eating nutritious foods and not smoking, we reduce our risk of heart disease and cancer. But the belief that a fighting spirit helps us to recover from injury or illness goes beyond healthful behavior. It reflects the persistent view that personality or a way of thinking can raise or reduce the likelihood of illness.

The psychosomatic hypothesis, which was popular in the mid-20th century, held that repressed emotional conflict was at the core of many physical diseases: Hypertension was the product of the inability to deal with hostile impulses. Ulcers were caused by unresolved fear and resentment. And women with breast cancer were characterized as being sexually inhibited, masochistic and unable to deal with anger.

Although modern doctors have rejected those beliefs, in the past 20 years, the medical literature has increasingly included studies examining the possibility that positive characteristics like optimism, spirituality and being a compassionate person are associated with good health. And books on the health benefits of happiness and positive outlook continue to be best sellers.

But there’s no evidence to back up the idea that an upbeat attitude can prevent any illness or help someone recover from one more readily. On the contrary, a recently completed study of nearly 60,000 people in Finland and Sweden who were followed for almost 30 years found no significant association between personality traits and the likelihood of developing or surviving cancer. Cancer doesn’t care if we’re good or bad, virtuous or vicious, compassionate or inconsiderate. Neither does heart disease or AIDS or any other illness or injury.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

photo { David Maisel }

flashback, health, psychology | February 5th, 2011 9:33 pm

In the history of inkblots, the experiment of Hermann Rorschach [1884-1922] is the most famous moment: a controversial attempt to establish a scientific personality assessment based on ten standard Rorschach inkblots. Then comes Andy Warhol, who in the 1980s reconnects inkblots with the art that came before. He did these huge, very sexual, strange, hieratic paintings which he called ‘Rorschach Paintings’ - although they were, in fact, entirely of his own invention. At the opening a journalist asked him what they meant and Warhol - in that amazing, neutral, “I’m a mirror” way of his– said, “Oh, I made a mistake, I got that wrong. I thought the idea was that you make your own inkblots and the psychiatrist interprets them. If I’d known, I’d just have copied the originals!” (…)

there have been inkblot tests around for ages, but in the 19th century they took over from silhouettes as the parlour game, partly due to a German doctor and poet called Justinus Koerner, who was a friend of the German Romantics and was interested in the nascent science of psychology and such things. He’d write endless letters, and he doodled in them, and started playing around with inkblots. He was the one who worked out that you could make inkblots symmetrical by folding them over.

{ The Browser | Continue reading }

related { Rorschach Test – Psychodiagnostic Plates: The ten inkblots + Decryption }

image { John Waters, Director’s cuts }

flashback, psychology, warhol | February 5th, 2011 8:26 pm

Harris has conducted two studies that show we may not enjoy watching a movie for two reasons: what we’re watching and who we’re watching it with. Particularly, the combination of watching a steamy love scene with your parents proved to be most unpleasant. (…)

The study focused on those uncomfortable movie-viewing moments and how viewers acted during the movie and after it. Harris said the gender of the viewer influenced reactions, a somewhat surprising result.

“Contrary to gender stereotypes, women were actually more likely to talk about it, both during the movie and after,” Harris said. “Men were more likely to do the avoidance types of responses: start talking about something else, not say anything at all or pretend it didn’t bother them.”

{ Kansas City University | Continue reading }

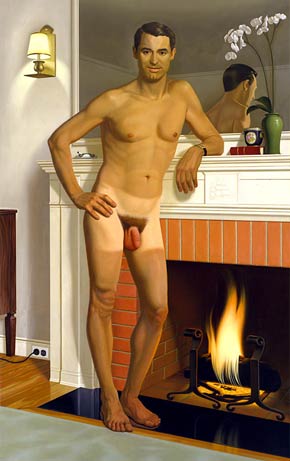

painting { Cary Grant by Kurt Kauper }

psychology, relationships | February 3rd, 2011 5:38 pm

The simple act of closing our eyes has a significant effect on our moral judgement and behaviour. Eugene Caruso and Francesca Gino, who made the observation, think the effect has to do with mental simulation, whereby having our eyes closed causes us to simulate scenarios more vividly. In turn this triggers more intense emotion. (…)

Overall, there was no evidence that the eyes-closed participants had simply paid more attention to the scenario than the eyes-open participants, but they did experience more negative, guilt-based emotion and it’s this effect that probably underlies the study’s central finding.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

eyes, psychology | February 2nd, 2011 3:57 pm

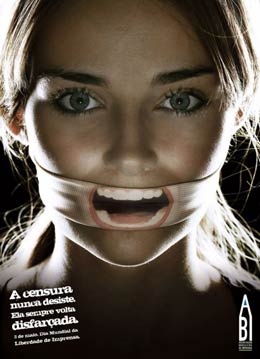

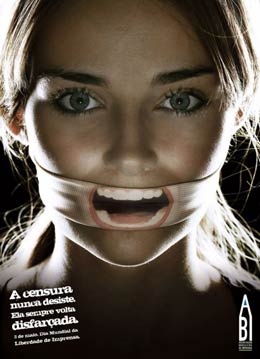

A double bind is an emotionally distressing dilemma in communication in which an individual (or group) receives two or more conflicting messages, in which one message negates the other. This creates a situation in which a successful response to one message results in a failed response to the other (and vice versa), so that the person will be automatically wrong regardless of response.

Double bind theory was first described by Gregory Bateson and his colleagues in the 1950s.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Linguistics, psychology | February 2nd, 2011 3:39 pm

You can tell a person’s personality from the words they use. Neurotics have a penchant for negative words; agreeable types for words pertaining to socialising; and so on. We know this from recordings of people’s speech and from brief writing tasks. Now Tal Yarkoni has extended this line of research to the blogosphere.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

For pop-language watchers, January marks the end of the words-of-the-year ritual that has so far given us ‘refudiate’ (New Oxford American Dictionary), ‘austerity’ (Merriam-Webster), and ’spillcam’ (Global Language Monitor). On Friday, members of the American Dialect Society will meet to consider the likes of ‘vuvuzela,’ ‘halfalogue,’ and ‘gleek’ for spots on its 2010 list.

Not all the annual wordfests, however, are celebratory. Since 1976, Lake Superior State University in Michigan has been issuing a list of words and phrases to be banished ‘for mis-use, over-use, and general uselessness.’

{ Boston Globe | Continue reading }

Linguistics, psychology | February 1st, 2011 4:24 pm

The experience of pleasure is the result of mechanisms designed to bring about (outcomes that would have led to) fitness gains. When Jared Diamond asked Why is Sex Fun, the answer had to do with the fact that evolved motivational systems are designed to drive organisms to do fitness-enhancing things, like having sex.

Now, I want to emphasize that this is speculative, but it seems to me that a key piece here is that humans seem to benefit from discovering certain kinds of new information they didn’t previously know. One way we do this is to read blogs like this one, but there are any number of other ways. The pleasure we take in new information depends on a number of factors, perhaps including how hard it is to get (easier is generally better), how many other people might be able to get it easily (fewer is often better, which cuts against the previous factor), the value of the information, how confident we are that it’s true, and so on. Gossip and Wikileaks are both, in a sense, satisfying our evolved appetites for finding out secrets, previously unknown and possibly useful information.

{ Evolutionary Psychology | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology | January 14th, 2011 8:00 pm

There are now roughly 2 billion Internet users worldwide. Five billion earthlings have cell phones. That scale of connectivity offers staggering power: In a few seconds, we can summon almost any fact, purchase a replacement hubcap or locate a cabin mate from those halcyon days at Camp Tewonga. We can call, email, text or chat online with our colleagues, friends and family just about anywhere.

Yet, along with the power has come the feeling that digital devices have invaded our every waking moment. We’ve had to pass laws to get people off their cell phones while driving. Backlit iPads slither into our beds for midnight Words With Friends trysts. Sitcoms poke fun at breakfast tables where siblings text each other to ask that the butter be passed. (According to a Nielsen study, the average 13- to 17-year-old now deals with 3,339 texts a month.)

We even buy new technology to cure new problems created by new technology: There’s an iPhone app that uses the device’s built-in camera to show the ground in front of a user as a backdrop on the keypad. “Have you ever tried calling someone while walking with your phone only to run into something because you can’t see where you’re going?” goes the sales pitch. (…)

A growing number of researchers here and elsewhere are exploring the social and psychological consequences of virtual experience and digital incursion. Researchers observe the blurring boundaries between real and virtual life, challenge the vaunted claims of multitasking, and ponder whether people need to establish technology-free zones.

{ Stanford magazine | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships, technology, uh oh | January 12th, 2011 7:20 pm

Imagine a world where people lacked confidence. We would scarcely be able to face a new day, struggling to summon the courage to show our work to our bosses or apply for a new job. Surgeons would be racked with doubt about upcoming operations. Military commanders would hesitate at key moments when decisiveness was essential.

Confidence is so vital even for the mundane activities of everyday life that we take it for granted. (…) Confidence is widely held to be an almost magic ingredient of success in sports, entertainment, business, the stock market, combat and many other domains. At the same time, confidence can be dangerous.

Confidence in excess—overconfidence—can easily burn out of control and cause costly decision-making errors, policy failures, and wars. For example, overconfidence has been blamed for a string of major disasters from the 1990s dotcom bubble, to the 2008 collapse of the banks, to the ongoing foot-dragging over climate change (“it won’t happen to me”). These events are no blip in the longer timeline of human endeavor. Historians and political scientists have blamed overconfidence for a range of fiascos, from the First World War to Vietnam to Iraq.

We may be surprised by the recurring problem of overconfidence—why don’t people learn from their mistakes? As the archetypal self-doubter Woody Allen suggested, “Confidence is what you have before you understand the problem.” But the recurrence of overconfidence is no surprise to psychologists.

All mentally healthy people tend to have so-called “positive illusions” about our abilities, our control over events, and our vulnerability to risk. Numerous studies have shown that we overrate our intelligence, attractiveness, and skill. We also think we have better morals, health, and leadership abilities than others. (…)

Positive illusions appear to be undergirded by many different cognitive and motivational biases, all of which converge to boost people’s confidence. This is dangerous because people are more likely to think they are better than others, which makes aggression, conflict, and even war more likely. As psychologist Daniel Kahneman put it: “The bottom line is that all the biases in judgment that have been identified in the last 15 years tend to bias decision-making toward the hawkish side.”

{ Seed magazine | Continue reading }

psychology | January 11th, 2011 9:40 am

Author Rachel Aviv talked at length with a number of young people who had been identified as being ‘prodromal’ for schizophrenia, experiencing periodic delusions and at risk of converting to full-blown schizophrenia, following some of the at-risk individuals for a year. In December’s Harper’s, Aviv offered a sensitive, insightful account of their day-to-day struggles to maintain insight, recognizing which of their experiences are not real: Which way madness lies: Can psychosis be prevented? [PDF](…)

This post is my more speculative offering, contemplating the relation of the content of delusions to the cultural context in which they occur. How do the specific details of delusions arise and how might the particularity of any one person’s delusions affect the way that a delusional individual is treated by others? Are you mad if everyone around you talks as if they, too, were experiencing the same delusions?

{ Neuroanthropology | Continue reading }

From the point of view of natural right, Hobbes says, and Spinoza will take all of this up again but from the point of view of natural right, the most reasonable man in the world and the most complete madman are strictly the same. (…) The point of the view of natural right is: my right equals my power, the madman is the one who does what is in his power, exactly as the reasonable man is the one who does what is in his. They are not saying idiotic things, they are not saying that the madman and the reasonable man are similar, they are saying that there is no difference between the reasonable man and the madman from the point of view of natural right. Why? Because each one does everything that he can.

{ Deleuze | Continue reading }

psychology, science | January 11th, 2011 9:36 am

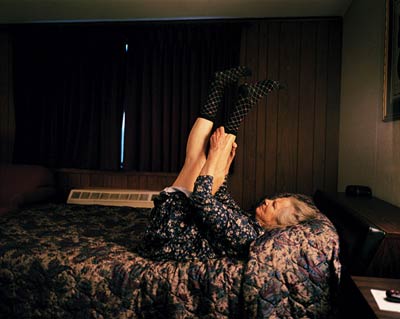

Life is not a long slow decline from sunlit uplands towards the valley of death. It is, rather, a U-bend.

When people start out on adult life, they are, on average, pretty cheerful. Things go downhill from youth to middle age until they reach a nadir commonly known as the mid-life crisis. So far, so familiar. The surprising part happens after that. Although as people move towards old age they lose things they treasure—vitality, mental sharpness and looks—they also gain what people spend their lives pursuing: happiness.

This curious finding has emerged from a new branch of economics that seeks a more satisfactory measure than money of human well-being. Conventional economics uses money as a proxy for utility—the dismal way in which the discipline talks about happiness. But some economists, unconvinced that there is a direct relationship between money and well-being, have decided to go to the nub of the matter and measure happiness itself.

{ The Economist | Continue reading }

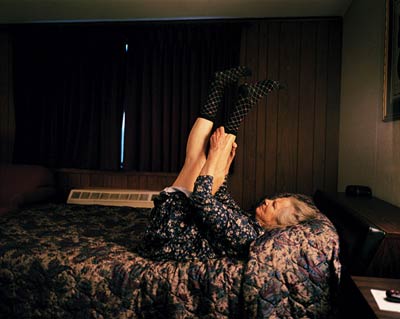

photo { The Haven of Contentment }

ideas, psychology | December 17th, 2010 5:36 pm

New research in Psychological Science found that the fear of being the target of malicious envy makes people act nicer to people they think might be jealous of them.

There are two types of envy says Niels van de Ven of Tilburg University and his coauthors: benign envy and malicious envy. People with benign envy are motivated to improve themselves, so they could be more like the person they envied. People with malicious envy want to bring the people above them down.

{ APS | Continue reading }

photo { David Stewart }

psychology, relationships | December 17th, 2010 4:50 pm

Although fiction treats themes of psychological importance, it has been excluded from psychology because it is seen as flawed empirical method. But fiction is not empirical truth. It is simulation that runs on minds of readers just as computer simulations run on computers. In any simulation coherence truths have priority over correspondences. Moreover, in the simulations of fiction, personal truths can be explored that allow readers to experience emotions — their own emotions — and understand aspects of them that are obscure, in relation to contexts in which the emotions arise.

{ Fiction as Cognitive and Emotional Simulation by Keith Oatley | Continue reading }

images { 1. Pinocchio | 2. Maurizio Cattelan, Daddy Daddy, 2008 | 3 }

ideas, psychology | December 16th, 2010 7:49 pm

Is the desire to know other people’s secrets a natural instinct – or a vulgar vice?

The need to maintain a barrier against the outside world may be one of our most basic human urges; but another is the lust to know the unknown, to observe and indulge in the privacy of others. In his book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life the sociologist Erving Goffman demonstrates how we all perform in various guises and to different groups of people, as if we were on stage. We preserve our “backstage” selves as an essential part of our identity – and it is this protected part of our personality that we attempt to mask, while harbouring a strong desire to penetrate those of others.

{ New Humanist | Continue reading }

photo { Man Ray }

psychology | December 16th, 2010 7:28 pm

Evolutionary biologists suggest there is a correlation between the size of the cerebral neocortex and the number of social relationships a primate species can have. Humans have the largest neocortex and the widest social circle — about 150, according to the scientist Robin Dunbar. Dunbar’s number — 150 — also happens to mirror the average number of friends people have on Facebook. Because of airplanes and telephones and now social media, human beings touch the lives of vastly more people than did our ancestors, who might have encountered only 150 people in their lifetime. Now the possibility of connection is accelerating at an extraordinary pace. As the great biologist E.O. Wilson says, “We’re in uncharted territory.”

{ TIME’s 2010 Person of the Year: Mark Zuckerberg | Continue reading | A map of the world, as drawn by Facebook }

psychology, relationships, social networks | December 15th, 2010 12:39 pm

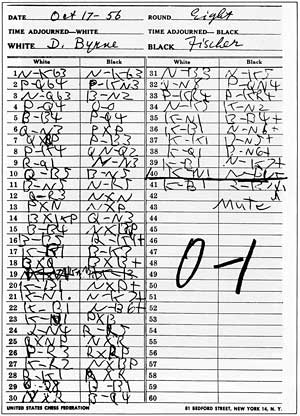

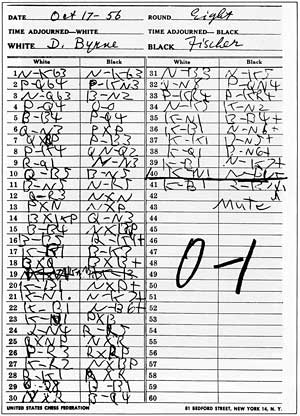

By most all accounts a brilliant mind, Fischer was perhaps the most visionary chess player since José Raul Capablanca, a Cuban who held the world title for six years in the 1920s. Fischer’s innovative, daring play — at age 13, he defeated senior master (and former U.S. Open champion) Donald Byrne in what is sometimes called “The Game of the Century” — made him a hero figure to millions in the United States and throughout the world. In 1957, Fischer became the youngest winner of the U.S. chess championship — he was just 14 — before going on to beat Spassky for the world title in 1972.

But Fischer forfeited that title just three years later, refusing to defend his crown under rules proposed by the World Chess Federation, and he played virtually no competitive chess in ensuing decades, retreating, instead, into isolation and seeming paranoia. Because of a series of rankly anti-Semitic public utterances and his praise, on radio, for the Sept. 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, at his death, Fischer was seen by much of the world as spoiled, arrogant and mean-spirited.

In recent years, however, researchers have come to understand that Bobby Fischer was psychologically troubled from early childhood. Careful examination of his life and family shows that he likely suffered with mental illness that may never have been properly diagnosed or treated.

{ Miller-McCune | Continue reading | Donald Byrne vs Robert James Fischer, “The Game of the Century,” 1956 | select Java Viewer and press set }

chess, psychology | December 14th, 2010 4:00 pm

One of the most surprising findings is that people have a natural aversion to inequality. We tend to prefer a world in which wealth is more evenly distributed, even if it means we have to get by with less.

Consider this recent experiment by a team of scientists at Caltech, published earlier this year in the journal Nature. The study began with 40 subjects blindly picking ping-pong balls from a hat. Half of the balls were labeled “rich,” while the other half were labeled “poor.” The rich subjects were immediately given $50, while the poor got nothing. Such is life: It’s rarely fair.

The subjects were then put in a brain scanner and given various monetary rewards, from $5 to $20. They were also told about a series of rewards given to a stranger. The first thing the scientists discovered is that the response of the subjects depended entirely on their starting financial position. For instance, people in the “poor” group showed much more activity in the reward areas of the brain (such as the ventral striatum) when given $20 in cash than people who started out with $50. This makes sense: If we have nothing, then every little something becomes valuable.

But then the scientists found something strange. When people in the “rich” group were told that a poor stranger was given $20, their brains showed more reward activity than when they themselves were given an equivalent amount. In other words, they got extra pleasure from the gains of someone with less.

{ Wall Street Journal | Continue reading }

photos { David Stewart | Valerie Chiang }

economics, neurosciences, psychology | December 13th, 2010 10:15 pm

Repetition is used everywhere—advertising, politics and the media—but does it really persuade us?

It seems too simplistic that just repeating a persuasive message should increase its effect, but that’s exactly what psychological research finds (again and again). Repetition is one of the easiest and most widespread methods of persuasion. In fact it’s so obvious that we sometimes forget how powerful it is.

People rate statements that have been repeated just once as more valid or true than things they’ve heard for the first time. (…)

Easy to understand = true

This is what psychologists call the illusion of truth effect and it arises at least partly because familiarity breeds liking. As we are exposed to a message again and again, it becomes more familiar. Because of the way our minds work, what is familiar is also true. Familiar things require less effort to process and that feeling of ease unconsciously signals truth (this is called cognitive fluency). (…)

Repetition is effective almost across the board when people are paying little attention, but when they are concentrating and the argument is weak, the effect disappears (Moons et al., 2008). In other words, it’s no good repeating a weak argument to people who are listening carefully.

{ PsyBlog | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology, uh oh | December 13th, 2010 8:15 pm

Many procrastinators do not realize that they are perfectionists, for the simple reason that they have never done anything perfectly, or even nearly so. They have never been told that something they did was perfect. (…)

Perfectionism is a matter of fantasy, not reality. Here’s how it works in my case. I am assigned some task, say, refereeing a manuscript for a publisher. I accept the task. (…) Immediately my fantasy life kicks in. I imagine myself writing the most wonderful referees report. (…)

This is perfectionism in the relevant sense. It’s not a matter of really ever doing anything that is perfect or even comes close. It is a matter of using tasks you accept to feed your fantasy of doing things perfectly, or at any rate extremely well. (…)

Well, seven or eight hours later I am done setting up the proxy server. (…)

Then what happens? I go on to other things. Most likely, the manuscript slowly disappears under subsequent memos, mail, half-eaten sandwiches, piles of files, and other things. (See the essay on “Horizontal Organization”.) I put it on my to do list, but I never look at my to do list. Then, in about six weeks, I get an email from the publisher, asking when she can expect the referee report. Maybe, if she has dealt with me before, this email arrives a bit before I promised the report. Maybe if she hasn’t, it arrives a few days after the deadline.

At this point, finally, I snap into action. My fantasy structure changes. I no longer fantasize writing the world’s best referee job ever. (…) At this point, I dig through the files, sandwiches, unopened correspondence, and, after a bit of panic (…) I find it. I take a couple of hours, read it, write a perfectly adequate report, and send it off.

{ John Perry | Continue reading }

experience, psychology | December 13th, 2010 8:00 pm

The brain may manage anger differently depending on whether we’re lying down or sitting up, according to a study published in Psychological Science. (…)

A field of study called ‘embodied cognition‘ has found lots of curious interactions between how the mind and brain manage our responses depending on the possibilities for action.

For example, we perceive distances as shorter when we have a tool in our hand and intend to use it, and wearing a heavy backpack causes hills to appear steeper.

Anger is a prime example where we feel motivated to ‘do something’. In the sitting position we’re much more ready to approach whatever’s annoying us than when we’re flat on our backs, and the researchers wondered whether these body positions were interacting with our motivations to change the brain’s response.

{ MindHacks | Continue reading }

photo { Tierney Gearon }

psychology, science | December 13th, 2010 7:42 pm