There are well over 100 small, irregular, asymmetric, and revolutionary wars ongoing around the world today. In these conflicts, there is much to be learned by anyone who has the responsibility of dealing with, analyzing, or reporting on national security threats generated by state and nonstate political actors who do not rely on highly structured organizations, large numbers of military forces, or costly weaponry—for example, transnational criminal organization (TCO)/gang/insurgent phenomena or politicized gangs. In any event, and in any phase of a criminal or revolutionary process, violent nonstate actors have played substantial roles in helping their own organizations and/or political patrons coerce radical political change and achieve putative power.

In these terms, TCO/gang/insurgent phenomena can be as important as traditional hegemonic nation-states in determining political patterns and outcomes in national and global affairs. Additionally, these cases demonstrate how the weakening of national stability, security, and sovereignty can indirectly contribute to personal and collective insecurity and to achieving radical political change. […]

Jamaican posses (gangs) are the byproducts of high levels of poverty and unemployment and lack of upward social mobility. Among other things, the posses represent the consequences of U.S. deportation of Jamaican criminals back to the island and, importantly, of regressive politics in Jamaican democracy. […]

It is estimated that there are at least 85 different posses operating on the island with anywhere between 2,500 to 20,000 members. Each posse operates within a clearly defined territory or neighborhood. The basic structure of a Jamaican posse is fluid but cohesive. Like most other gangs in the Americas, it has an all-powerful don or area leader at the apex of the organization, an upper echelon, a middle echelon, and the “workers” at the bottom of the social pyramid. The upper echelon coordinates the posse’s overall drug, arms, and human trafficking efforts. The middle group manages daily operational activities. The lowest echelon performs street-level sales, purchases, protection, and acts of violence as assigned. When posses need additional workers, they prefer to use other Jamaicans. However, as posses have expanded their markets, they have been known to recruit outsiders, such as African Americans, Trinidadians, Guyanese, and even Chinese immigrants, as mules and street-level dealers. They are kept ignorant of gang structure and members’ identities. If low-level workers are arrested, the posse is not compromised and the revenue continues to come in. […]

Jamaican posses are credited with being self-reliant and self-contained. They have their own aircraft, watercraft, and crews for pickup and delivery, and their own personnel to run legitimate businesses and conduct money-laundering tasks. In that connection, posses have expanded their operations into the entire Caribbean Basin, the United States, Canada, and Europe. The general reputation of Jamaican posses is one of high efficiency and absolute ruthlessness in pursuit of their territorial and commercial interests. Examples of swift and brutal violence include, but are not limited to, fire-bombing, throat-slashing, and dismemberment of victims and their families. Accordingly, Jamaican posses are credited with the highest level of violence in the English-speaking Caribbean and 60 percent of the crime in the region. […]

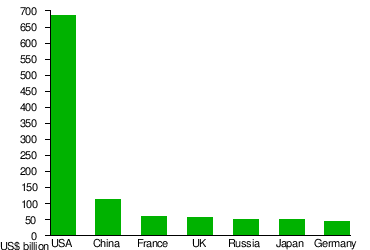

Today, it is estimated that any given gang-cartel combination earns more money annually from its illicit activities than any Caribbean country generates in legitimate revenues. Thus, individual mini-state governments in the region are simply overmatched by the gang phenomenon. The gangs and their various allies have more money, better arms, and more effective organizations than the states. […]

The great city of São Paulo, Brazil—the proverbial locomotive that pulls the train of the world’s eighth largest economy—was paralyzed by a great surprise in mid-May 2006. […] More than 293 attacks on individuals and groups of individuals were reported, hundreds of people were killed and wounded, and millions of dollars in damage was done to private and public property. Buses were torched, banks were robbed, personal residences were looted and vandalized, municipal buildings and police stations were attacked, and rebellions broke out in 82 prisons within São Paulo’s penal system. Transportation, businesses, factories, offices, banks, schools, and shopping centers were shut down. In all, the city was a frightening place during those days in May.

During that time, the PCC [one of the largest and most powerful gangs in the world] demonstrated its ability to coordinate simultaneous prison riots; destabilize a major city; manipulate judicial, political, and security systems; and shut down the formal Brazilian economy. The PCC also demonstrated its complete lack of principles through its willingness to indiscriminately kill innocent people, destroy public and private property, and suspend the quality-of-life benefits of a major economy for millions of people.

{ PRISM | Continue reading }