neurosciences

Scientists have traced chronic pain to a defect in one enzyme in a single region of the brain. Could this be a decisive turn in the battle against pain? (…)

As neuroscientists learn more about the biological basis of pain, the situation is finally beginning to change. Most remarkably, unfolding research shows that chronic pain can cause concrete, physiological changes in the brain. After several months of chronic pain, a person’s brain begins to shrink. The longer people suffer, the more gray matter they lose. (…)

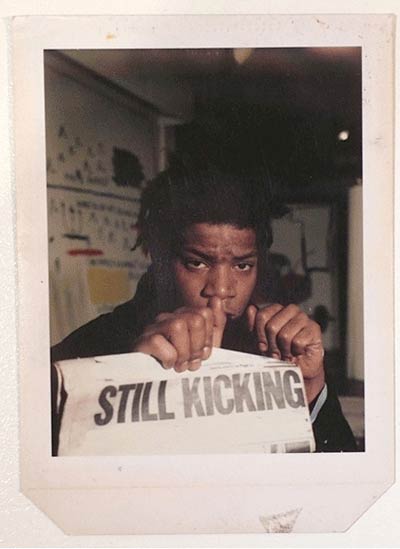

Normally, pain is triggered by a set of danger-sensing neurons, called nociceptors, that extend into the organs, muscles, and skin. Different types of nociceptors respond to different stimuli, including heat, cold, pressure, inflammation, and exposure to chemicals like cigarette smoke and teargas. Nociceptors can notify us of danger with fine-tuned precision. Heat nociceptors, for example, send out an alarm only when they’re heated to between 45 and 50 degrees Celsius (about 115 to 125 degrees Fahrenheit), the temperature at which some proteins start to coagulate and cause damage to cells and tissues.

For all that precision, we don’t automatically feel the signals as pain; often the information from nociceptors is parsed by the nervous system along the way. For instance, nociceptors starting in the skin extend through the body to swellings along the spinal cord. They relay their signals to other neurons in those swellings, called dorsal horns, which then deliver signals up to the brain stem. But dorsal horns also contain neurons coming down from the brain that can boost or squelch the signals. As a result, pain in one part of the body can block pain signals from another. If you stick your foot in cold water, touching a hot surface with your hand will hurt less.

{ Discovery | Continue reading }

brain, neurosciences | June 22nd, 2011 4:55 pm

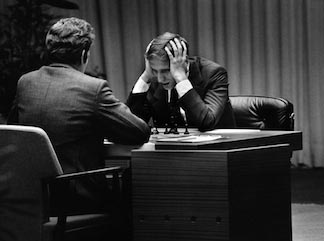

…looking at all the ways the conscious is just the littlest bit of what’s happening in the brain. Your brain does these massive computations under the hood all the time. And a hunch essentially is the result of all those computations. So it’s exactly like riding a bicycle, the way you don’t have to be consciously aware, in fact you cannot be consciously aware. Your consciousness has no access to the operations running under the hood that allow you to ride the bicycle, or for that matter that allow you to recognize somebody’s face. you don’t know how you recognize somebody’s face, you just do it effortlessly.

In both of these cases, it’s very hard to write computer programs to do this stuff, to ride a bicycle or recognize somebody’s face, because there’s massive computation going on there that’s required. Your brain does this all effortlessly and the hunch is when it serves up the end result of those computations.

Essentially the conscious mind is like a newspaper headline in the sense that all it ever wants is the summary, it doesn’t need to know all the details of how something happened, it just wants to know.

{ David Eagleman/Wired | Continue reading }

brain, neurosciences | June 17th, 2011 2:12 pm

What is a person? What is a human being? What is consciousness? There is a tremendous amount of enthusiasm at the moment about these questions.

They are usually framed as questions about the brain, about how the brain makes consciousness happen, how the brain constitutes who we are, what we are, what we want—our behavior. The thing I find so striking is that, at the present time, we actually can’t give any satisfactory explanations about the nature of human experience in terms of the functioning of the brain.

What explains this is really quite simple. You are not your brain. You have a brain, yes. But you are a living being that is connected to an environment; you are embodied, and dynamically interacting with the world. We can’t explain consciousness in terms of the brain alone because consciousness doesn’t happen in the brain alone.

In many ways, the new thinking about consciousness and the brain is really just the old-fashioned style of traditional philosophical thinking about these questions but presented in a new, neuroscience package. People interested in consciousness have tended to make certain assumptions, take certain things for granted. They take for granted that thinking, feeling, wanting, consciousness in general, is something that happens inside of us. They take for granted that the world, and the rest of our body, matters for consciousness only as a source of causal impingement on what is happening inside of us. Action has no more intimate connection to thought, feeling, consciousness, and experience. They tend to assume that we are fundamentally intellectual—that the thing inside of us which thinks and feels and decides is, in its basic nature, a problem solver, a calculator, a something whose nature is to figure out what there is and what we ought to do in light of what is coming in.

We should reject the idea that the mind is something inside of us that is basically matter of just a calculating machine. There are different reasons to reject this. But one is, simply put: there is nothing inside us that thinks and feels and is conscious. Consciousness is not something that happens in us. It is something we do.

{ Alva Noë/Edge | Continue reading }

photo { William Klein }

ideas, neurosciences | June 12th, 2011 8:20 pm

Affecting up to 80 percent of women, PMS is a familiar scapegoat. But women are affected by their cycles every day of the month. Hormone levels are constantly changing in a woman’s brain and body, changing her outlook, energy and sensitivity along with them.

About 10 days after the onset of menstruation, right before ovulation, women often feel sassier, Brizendine told LiveScience. Unconsciously, they dress sexier as surges in estrogen and testosterone prompt them to look for sexual opportunities during this particularly fertile period.

A week later, there is a rise in progesterone, the hormone that mimics valium, making women “feel like cuddling up with a hot cup of tea and a good book,” Brizendine said. The following week, progesterone withdrawal can make women weepy and easily irritated. “We call it crying over dog commercials crying,” Brizendine said.

For most women, their mood reaches its worst 12-24 hours before their period starts. (…)

Over the course of evolution, women may have been selected for their ability to keep young preverbal humans alive, which involves deducing what an infant or child needs — warmth, food, discipline — without it being directly communicated. This is one explanation for why women consistently score higher than men on tests that require reading nonverbal cues. Women not only better remember the physical appearances of others but also more correctly identify the unspoken messages conveyed in facial expressions, postures and tones of voice, studies show. (…)

Brain-imaging studies over the last 10 years have shown that male and female brains respond differently to pain and fear. And, women’s brains may be the more sensitive of the two. (…)

“A women’s sex drive is much more easily upset than a guy’s,” Brizendine said.

For women to get in the mood, and especially to have an orgasm, certain areas of her brain have to shut off. And any number of things can turn them back on.

A woman may refuse a man’s advances because she is angry, feeling distrustful — or even, because her feet are chilly, studies show.

{ LiveScience | Continue reading }

related { According to research, the more housework men do, the happier their wives are. }

brain, genders, neurosciences | June 11th, 2011 7:53 pm

Why we remember some scenes from early childhood and forget others has long intrigued scientists—as well as parents striving to create happy memories for their kids. One of the biggest mysteries: why most people can’t seem to recall anything before age 3 or 4.

Now, researchers in Canada have demonstrated that some young children can remember events from even before age 2—but those memories are fragile, with many vanishing by about age 10, according to a study in the journal Child Development this month.

{ WSJ | Continue reading }

photo { Garry Winogrand, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1957 }

brain, kids, memory, neurosciences | June 2nd, 2011 3:49 pm

The number of people we can truly be friends with is constant, regardless of social networking services like Twitter, according to a new study of the network.

Back in early 90s, the British anthropologist Robin Dunbar began studying the social groups of various kinds of primates. Before long, he noticed something odd.

Primates tend to maintain social contact with a limited number of individuals within their group. But here’s the thing: primates with bigger brains tended to have a bigger circle of friends. Dunbar reasoned that this was because the number of individuals a primate could track was limited by brain volume.

Then he did something interesting. He plotted brain size against number of contacts and extrapolated to see how many friends a human ought to be able to handle. The number turned out to be about 150.

Since then, various studies have actually measured the number of people an individual can maintain regular contact with. These all show that Dunbar was just about spot on (although there is a fair spread in the results).

What’s more, this number appears to have been constant throughout human history–from the size of neolithic villages to military units to 20th century contact books.

But in the last decade or so, social networking technology has had a profound influence on the way people connect. Twitter, for example, vastly increases the ease with which we can communicate with and follow others. It’s not uncommon for tweeters to follow and be followed by thousands of others.

So it’s easy to imagine that social networking technology finally allows humans to surpass the Dunbar number. Not so say Bruno Goncalves and buddies at Indiana University.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

related { What Do People Actually Tweet About? }

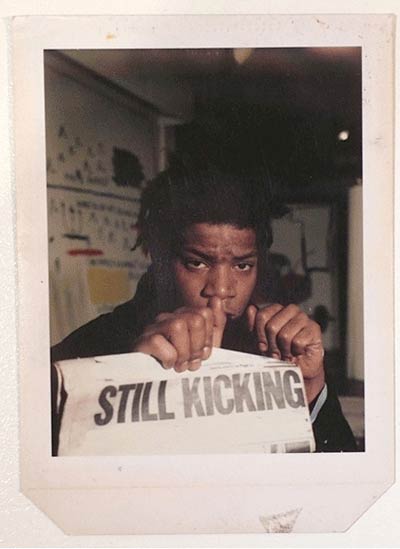

photo { Isaac McKay-Randozz }

neurosciences, relationships, social networks | May 30th, 2011 6:18 pm

Burundanga is a scary drug. (…) The scale of the problem in Latin America is not known, but a recent survey of emergency hospital admissions in Bogotá, Colombia, found that around 70 per cent of patients drugged with burundanga had also been robbed, and around three per cent sexually assaulted. “The most common symptoms are confusion and amnesia,” says Juliana Gomez, a Colombian psychiatrist. (…)

News reports allude to another, more sinister, effect: that the drug removes free will, effectively turning victims into suggestible human puppets. Although not fully understood by neuroscience, free will is seen as a highly complex neurological ability and one of the most cherished of human characteristics.

{ Wired UK | Continue reading }

Neuroscientists

increasingly describe our behaviour as the result of a chain of

cause-and-effect, in which one physical brain state or pattern of

neural activity inexorably leads to the next, culminating in a

particular action or decision. With little space for free choice in

this chain of causation, the conscious, deliberating self seems to

be a fiction. From this perspective, all the real action is

occurring at the level of synapses and neurotransmitters.

For now most of us are content to believe that we have control over

our own lives, but what would happen if we lost our faith in free

will?

{ Susan Sayler | Continue reading }

oil on canvas { Aron Wiesenfeld, The Wedding Party }

controversy, ideas, neurosciences | May 16th, 2011 5:30 pm

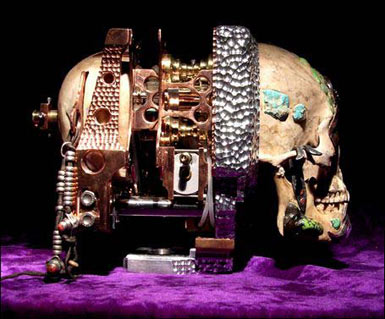

A new study from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden shows that the brain has built-in mechanisms that trigger an automatic reaction to someone who refuses to share. The reaction derives from the amygdala, an older part of the brain. The subjects’ sense of justice was challenged in a two-player money-based fairness game, while their brain activity was registered by an MR scanner. When bidders made unfair suggestions as to how to share the money, they were often punished by their partners even if it cost them. A drug that inhibits amygdala activity subdued this reaction to unfairness.

{ Karolinska Institutet | Continue reading }

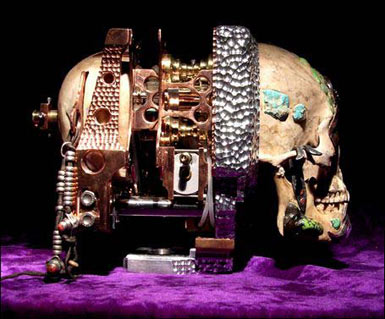

image { Wayne Belger’s Yama (Tibetan Skull Camera) }

neurosciences | May 5th, 2011 1:16 pm

There’s no such thing as a free lunch, and that goes for your brain, too. Every time you amass the willpower to do anything, it has mental costs. (…)

Starting an activity seems to take a larger of willpower and other resources than keeping going with it. Required activation energy can be adjusted over time – making something into a routine lowers the activation energy to do it. (…)

This is a major hurdle for a lot of people in a lot of disciplines – just getting started.

{ LifeHacker | Continue reading }

guide, neurosciences | May 4th, 2011 11:52 am

When we think of demographics that are easily distracted, we tend to think of younger generations, people on their phones over dinner or texting while driving, or only listening to you with one ear while they listen to their ipod with the other. But when we’re talking about cognitive tasks like working memory, the ability to work without distractions is actually highest when you’re younger, and decreases with age. Working memory is the ability to store bits of information and manipulate them over a short period of time. How long the working memory lasts for depends on what you’re trying to remember (say, a string of words that makes sense over a string of numbers that doesn’t), the amount of information you’re trying to process, and on how distracted you are.

{ Neurotic Physiology | Continue reading }

memory, neurosciences | May 2nd, 2011 6:10 pm

“Neuroscience gives us a completely new perspective,” says Marco Iacoboni, UCLA professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences. “For millennia we’ve relied on people’s words. Neuroscience uncovers the things that people don’t say — and often can’t say, because there is a lot that goes on in our brain that is difficult to verbalize, or that we aren’t even aware of.”

{ UCLA magazine | Continue reading }

…what neuroscience can tell us about ourselves: it reveals some of the most important conditions that are necessary for behavior and awareness.

What neuroscience does not do, however, is provide a satisfactory account of the conditions that are sufficient for behavior and awareness. Its descriptions of what these phenomena are and of how they arise are incomplete in several crucial respects, as we will see. (…)

While to live a human life requires having a brain in some kind of working order, it does not follow from this fact that to live a human life is to be a brain in some kind of working order.

{ Raymond Tallis/The New Atlantis | Continue reading }

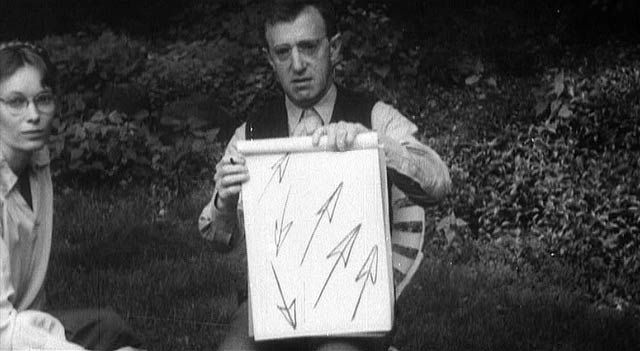

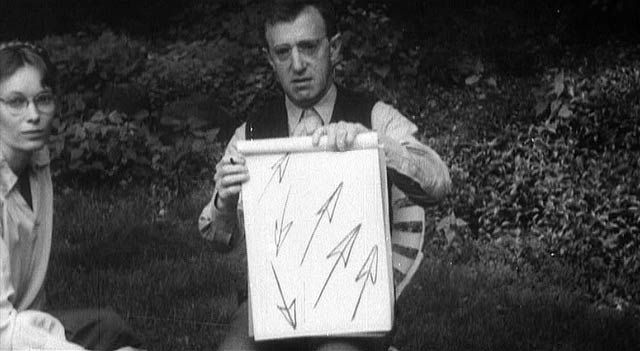

screenshot { Zelig, 1983 }

neurosciences | April 26th, 2011 8:22 pm

Human minds evolved to constantly scan for novelty, lest we miss any sign of food, danger or, on a good day, mating opportunities.

But the modern world bombards us with stimuli, a nonstop stream of e-mails, chats, texts, tweets, status updates and video links to piano playing cats.

There’s growing concern among scientists that indulging in these ceaseless disruptions isn’t good for our brains, in much the way that excessive sugar or fat - other things we evolved to crave when they were in shorter supply - isn’t good for our bodies.

And some believe it’s time to consider a technology diet.

A team at UCSF published a study last week that found further evidence that multitasking impedes short-term memory, especially among older adults. Researchers there previously found that distractions of the sort that smart phones and social networks present can hinder long-term memory and mental performance.

{ SF Chronicle | Continue reading }

artwork { Samuel Ekwurtzel, 11:34 }

health, memory, neurosciences, science, technology | April 19th, 2011 4:50 pm

A spectacular case of psychosis, rather oddly described as ‘Methamphetamine Induced Synesthesia’, in a case report just published in The American Journal on Addictions.

The report concerns a 30-year-old gentleman from the Iranian city of Shiraz with a long-standing history of drug use who recently started smoking crystal:

Six months PTA [prior to admission] (October 2009), he started smoking methamphetamine once a day, and gradually increased the frequency to three times a day.

Two months PTA (January 2010), he developed symptoms of auditory and visual hallucinations (seeing fairies around him that talked to him and forced him to conduct aggressive behavior), self-injury, and suicidal attempts.

He developed odd behaviors such as boiling animal statues. He was hearing the voices of colors, which were in the carpet. Colors moved around and talked to each other about the patient. He also saw the heads of different kinds of animals gathering on a board, and they talked to him.

Finally, his mother brought him to the emergency room of Ebnecina Psychiatric Hospital in Shiraz.

{ Mind Hacks | Continue reading }

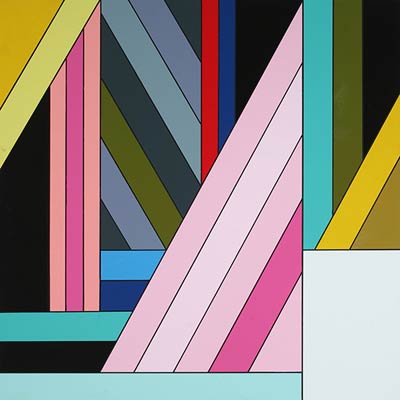

artwork { James Marshall }

drugs, neurosciences | April 19th, 2011 4:20 pm

Eagleman has collected hundreds of stories like his, and they almost all share the same quality: in life-threatening situations, time seems to slow down. (…)

Eagleman is thirty-nine now and an assistant professor of neuroscience at Baylor College of Medicine, in Houston. (…)

The brain is a remarkably capable chronometer for most purposes. It can track seconds, minutes, days, and weeks, set off alarms in the morning, at bedtime, on birthdays and anniversaries. Timing is so essential to our survival that it may be the most finely tuned of our senses. In lab tests, people can distinguish between sounds as little as five milliseconds apart, and our involuntary timing is even quicker. If you’re hiking through a jungle and a tiger growls in the underbrush, your brain will instantly home in on the sound by comparing when it reached each of your ears, and triangulating between the three points. The difference can be as little as nine-millionths of a second.

Yet “brain time,” as Eagleman calls it, is intrinsically subjective. “Try this exercise,” he suggests in a recent essay. “Put this book down and go look in a mirror. Now move your eyes back and forth, so that you’re looking at your left eye, then at your right eye, then at your left eye again. When your eyes shift from one position to the other, they take time to move and land on the other location. But here’s the kicker: you never see your eyes move.” There’s no evidence of any gaps in your perception—no darkened stretches like bits of blank film—yet much of what you see has been edited out. Your brain has taken a complicated scene of eyes darting back and forth and recut it as a simple one: your eyes stare straight ahead. Where did the missing moments go?

The question raises a fundamental issue of consciousness: how much of what we perceive exists outside of us and how much is a product of our minds?

{ The New Yorker | Continue reading }

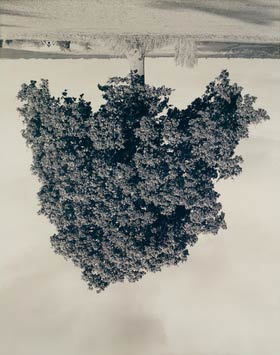

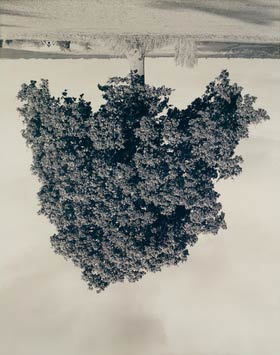

photo { Rodney Graham }

neurosciences, time | April 18th, 2011 7:00 pm

In the present study 24 university students read four different texts in four conditions:

(1) while listening to music they preferred to listen to while studying;

(2) while listening to music they did not prefer to listen to while studying;

(3) while listening to a recording of noise from a café; and finally

(4) in silence.

After each text they took a reading-comprehension test. Eye movement data were recorded for all participants in all conditions.

A main effect for the reading-comprehension scores revealed that the participants scored significantly lower after they had been listening to the non-preferred music while reading, compared with reading in silence.

{ SAGE | Continue reading }

photo { Kyoko Hamada }

music, neurosciences | April 13th, 2011 5:28 pm

Anecdotal reports suggest that some users of ecstasy (MDMA) experience increased feelings of empathy and are more social while under influence of the drug. Such effects may contribute to the timing and frequency of ecstasy use and may also contribute to risk of abuse or dependence. Understanding this phenomenon in more detail might provide clinicians with better strategies to reduce use and the associated complications of ecstasy use.

Studying acute effects of illicit drugs is difficult under natural conditions. Users of ecstasy commonly also use alcohol, nictoine and other illicit drugs in the context of ecstasy use. Isolating psychological effects of one agent in this type of environment is difficult if not impossible. One alternative is to admiinster ecstasy in a laboratory setting with subjects blind to whether ecstasy or placebo is being administered. However, this approach poses significant ethical challenges. One approach, is to limit human study in the lab to those who have previously use ecstasy and intend to continue using. (…)

A study in Biological Psychiatry took this approach when over four sessions, healthy ecstasy using volunteers received either a low or high dose of MDMA, a dose of methamphetamine (METH) or placebo. (…)

Findings suggest MDMA increases social approach (sociability). The study supports the possibility that increased social behavior with MDMA might be due to a reduced sensitivity to negative emotions of others rather than increasing recognition of positive emotions in others.

{ Brain Posts | Continue reading }

photo { Noritoshi Hirakawa }

drugs, neurosciences, photogs, relationships | April 13th, 2011 2:57 pm

We often remember things by relying on the overall gist of an event—for example, instead of storing every detail about our last birthday, we tend to remember abstract things like “I had a fun party” or “I was in a grumpy mood because I felt old.”

This strategy allows us to remember more things about an event, but there’s one major drawback: by storing memories based on gist, we actually change how we remember the event. This happens because we are biased to remember things that are consistent with our overall summary of the event. So if we remember the birthday party was “super fun” overall, we’ll exaggerate how we remember the details—the average chocolate cake is now “insanely good”, and the 10 friends who were there becomes a “huge crowd.” (…)

As it turns out, gist changes the way we remember an event after just one second.

{ I on Psych | Continue reading }

photo { Noah Kalina }

memory, neurosciences | April 8th, 2011 4:15 pm

In philosophy of mind, a “cerebroscope” is a fictitious device, a brain–computer interface in today’s language, which reads out the content of somebody’s brain. An autocerebroscope is a device applied to one’s own brain. You would be able to see your own brain in action, observing the fleeting bioelectric activity of all its nerve cells and thus of your own conscious mind. There is a strange loopiness about this idea. The mind observing its own brain gives rise to the very mind observing this brain. How will this weirdness affect the brain? Neuroscience has answered this question more quickly than many thought possible.

But first, a bit of background. Epileptic seizures—hypersynchronized, self-maintained neural discharges that can sometimes engulf the entire brain—are a common neurological disorder. These recurring and episodic brain spasms are kept in check with drugs that dampen excitation and boost inhibition in the underlying circuits. Medication does not always work, however. When a localized abnormality, such as scar tissue or developmental miswiring, is suspected of triggering the seizure, neurosurgeons may remove the offending tissue. (…)

Under Fried’s supervision, a group from my laboratory—Rodrigo Quian Quiroga, Gabriel Kreiman and Leila Reddy—discovered a remarkable set of neurons in the jungles of the medial temporal lobe, the source of many epileptic seizures. This region, deep inside the brain, which includes the hippocampus, turns visual and other sensory percepts into memories.

We enlisted the help of several epileptic patients. While they waited for their seizures, we showed them about 100 pictures of familiar people, animals, landmark buildings and objects. We hoped one or more of the photographs would prompt some of the monitored neurons to fire a burst of action potentials. Most of the time the search turned up empty-handed, although sometimes we would come upon neurons that responded to categories of objects, such as animals, outdoor scenes or faces in general. But a few neurons were much more discerning. One hippocampal neuron responded only to photos of actress Jennifer Aniston but not to pictures of other blonde women or actresses; moreover, the cell fired in response to seven very different pictures of Jennifer Aniston. (…)

Nobody is born with cells selective for Jennifer Aniston. (…) The networks in the medial temporal lobe recognize such repeating patterns and dedicate specific neurons to them. You have concept neurons that encode family members, pets, friends, co-workers, the politicians you watch on TV, your laptop, that painting you adore.

Conversely, you do not have concept cells for things you rarely encounter.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

ideas, neurosciences | April 6th, 2011 6:00 pm

For 40 years, psychologists thought that humans and animals kept time with a biological version of a stopwatch. Somewhere in the brain, a regular series of pulses was being generated. When the brain needed to time some event, a gate opened and the pulses moved into some kind of counting device.

One reason this clock model was so compelling: Psychologists could use it to explain how our perception of time changes. Think about how your feeling of time slows down as you see a car crash on the road ahead, how it speeds up when you’re wheeling around a dance floor in love. Psychologists argued that these experiences tweaked the pulse generator, speeding up the flow of pulses or slowing it down.

But the fact is that the biology of the brain just doesn’t work like the clocks we’re familiar with. Neurons can do a good job of producing a steady series of pulses. They don’t have what it takes to count pulses accurately for seconds or minutes or more. The mistakes we make in telling time also raise doubts about the clock models. If our brains really did work that way, we ought to do a better job of estimating long periods of time than short ones. Any individual pulse from the hypothetical clock would be a little bit slow or fast. Over a short time, the brain would accumulate just a few pulses, and so the error could be significant. The many pulses that pile up over long stretches of time should cancel their errors out. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. As we estimate longer stretches of time, the range of errors gets bigger as well.

{ Discover | Continue reading }

neurosciences, time | March 28th, 2011 5:48 pm

Over the last few decades many Buddhists and quite a few neuroscientists have examined Buddhism and neuroscience, with both groups reporting overlap. (…)

Neuroscience tells us the thing we take as our unified mind is an illusion, that our mind is not unified and can barely be said to “exist” at all. Our feeling of unity and control is a post-hoc confabulation and is easily fractured into separate parts. As revealed by scientific inquiry, what we call a mind (or a self, or a soul) is actually something that changes so much and is so uncertain that our pre-scientific language struggles to find meaning.

Buddhists say pretty much the same thing. They believe in an impermanent and illusory self made of shifting parts. They’ve even come up with language to address the problem between perception and belief. Their word for self is anatta, which is usually translated as ‘non self.’ One might try to refer to the self, but the word cleverly reminds one’s self that there is no such thing.

{ Seed | Continue reading }

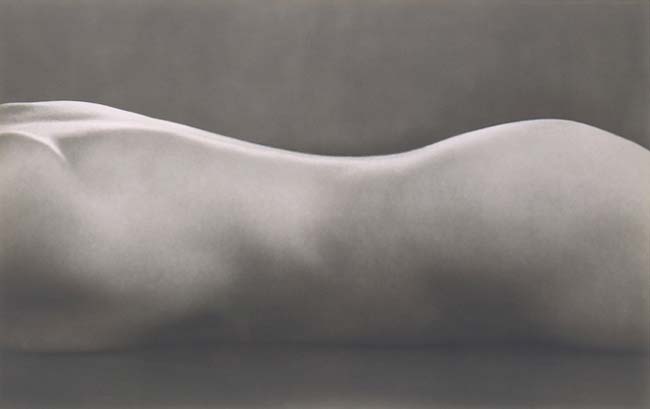

photo { Edward Weston }

ideas, neurosciences | March 18th, 2011 3:40 pm