neurosciences

People’s capacity to generate creative ideas is central to technological and cultural progress. Despite advances in the neuroscience of creativity, the field lacks clarity on whether a specific neural architecture distinguishes the highly creative brain. […]

We identified a brain network associated with creative ability comprised of regions within default, salience, and executive systems—neural circuits that often work in opposition. Across four independent datasets, we show that a person’s capacity to generate original ideas can be reliably predicted from the strength of functional connectivity within this network, indicating that creative thinking ability is characterized by a distinct brain connectivity profile.

{ PNAS | Continue reading | Read more }

related { Neurobiological differences between classical and jazz musicians at high and low levels of action planning }

music, neurosciences | January 22nd, 2018 12:19 pm

Neurobiological research on memory has tended to focus on the cellular mechanisms involved in storing information, known as persistence, but much less attention has been paid to those involved in forgetting, also known as transience. It’s often been assumed that an inability to remember comes down to a failure of the mechanisms involved in storing or recalling information.

“We find plenty of evidence from recent research that there are mechanisms that promote memory loss, and that these are distinct from those involved in storing information,” says co-author Paul Frankland.

One recent study in particular done by Frankland’s lab showed that the growth of new neurons in the hippocampus seems to promote forgetting. This was an interesting finding since this area of the brain generates more cells in young people. The research explored how forgetting in childhood may play a role in why adults typically do not have memories for events that occurred before the age of four years old.

{ University of Toronto | Continue reading }

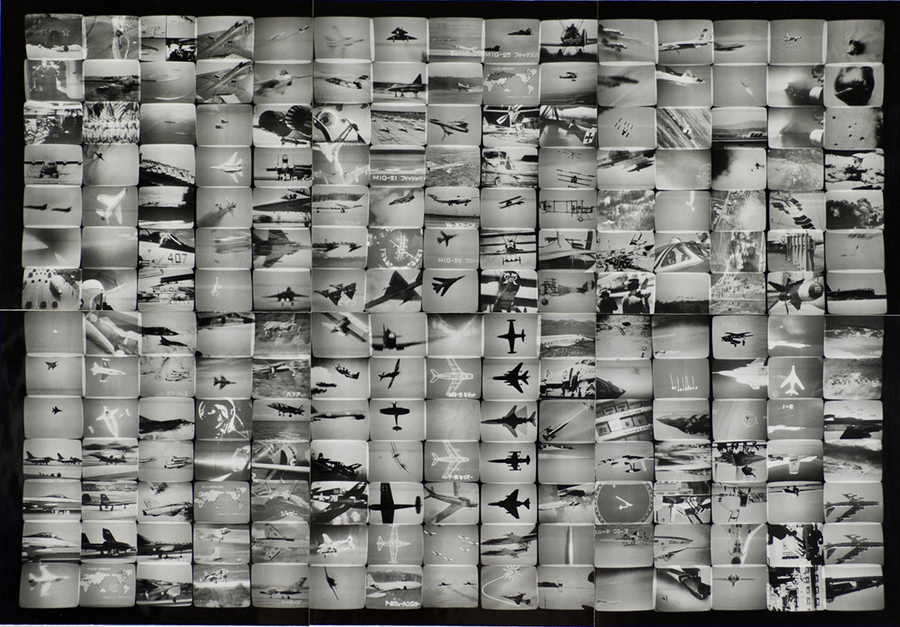

art { Masao Mochizuki, The Air Power of the World, 1976 }

memory | July 10th, 2017 4:15 pm

When you’re doing two things at once – like listening to the radio while driving – your brain organizes itself into two, functionally independent networks, almost as if you temporarily have two brains. That’s according to a fascinating new study from University of Wisconsin-Madison neuroscientists Shuntaro Sasai and colleagues.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

art { Harri Peccinotti }

brain, neurosciences | December 9th, 2016 4:23 pm

Remembering the past is a complex phenomenon that is subject to error. The malleable nature of human memory has led some researchers to argue that our memory systems are not oriented towards flawlessly preserving our past experiences. Indeed, many researchers now agree that remembering is, to some degree, reconstructive. Current theories propose that our capacity to flexibly recombine remembered information from multiple sources – such as distributed memory records, inferences, and expectations – helps us to solve current problems and anticipate future events. One implication of having a reconstructive and flexible memory system is that people can develop rich and coherent autobiographical memories of entire events that never happened.

In this article, we revisit questions about the conditions under which participants in studies of false autobiographical memory come to believe in and remember fictitious childhood experiences. […]

Approximately one-third of participants showed evidence of a false memory, and more than half showed evidence of believing that the [fictitious] event occurred in the past.

{ Memory | Continue reading }

Photo photo { Brooke Nipar }

memory | December 9th, 2016 4:23 pm

Normal aging is known to be accompanied by loss of brain substance.

Machine learning was used to estimate brain ages in meditators and controls.

At age 50, brains of meditators were estimated to be 7.5 years younger than that of controls.

These findings suggest that meditation may be beneficial for brain preservation.

{ NeuroImage | Continue reading }

image { Jonathan Puckey }

brain, neurosciences | April 15th, 2016 5:34 am

The First Brain - The Brain Occupying the Space in the Skull

All of us are familiar with the general presence and functioning of this brain as a receiver of information which then gets processed.

The Second Brain - The brain in the gut

It has been proven that the very same cells and neural network that is present in the brain in the skull is present in the gut as well and releases the same neurotransmitters as the brain in the skull. Not just that, about 90 percent of the bers in the primary visceral nerve, the vagus, carry information from the gut to the brain and not the other way around.

The Third Brain - The Global Brain

This is connected to the neural network that extends from each being on this planet beyond the con nes of the skull and the anatomy of the gut. It is inter-dimensional in nature and contains all frequencies of energies (low and high) and their corresponding information.

[…]

Every human being is born with the three brains described above, but Autistic Beings are more connected and more in-tune with all three simultaneously. But make no mistake – most autistic beings are not necessarily aware of the existence or their connection to these three brains beyond their volitional control although they are accessing information from all three to varying degrees almost all the time.

One of the manifestations of being tuned-in to this third brain is Telepathy.

{ Journal of Neurology and Neurobiology | PDF }

photo { Video screen shows images of blue sky on Tiananmen Square in Beijing, January 23, 2013 }

neurosciences | February 16th, 2016 12:39 pm

After medicine in the 20th century focused on healing the sick, now it is more and more focused on upgrading the healthy, which is a completely different project. And it’s a fundamentally different project in social and political terms, because whereas healing the sick is an egalitarian project […] upgrading is by definition an elitist project. […] This opens the possibility of creating huge gaps between the rich and the poor […]Many people say no, it will not happen, because we have the experience of the 20th century, that we had many medical advances, beginning with the rich or with the most advanced countries, and gradually they trickled down to everybody, and now everybody enjoys antibiotics or vaccinations or whatever. […]

There were peculiar reasons why medicine in the 20th century was egalitarian, why the discoveries trickled down to everybody. These unique conditions may not repeat themselves in the 21st century. […] When you look at the 20th century, it’s the era of the masses, mass politics, mass economics. Every human being has value, has political, economic, and military value. […] This goes back to the structures of the military and of the economy, where every human being is valuable as a soldier in the trenches and as a worker in the factory.

But in the 21st century, there is a good chance that most humans will lose, they are losing, their military and economic value. This is true for the military, it’s done, it’s over. The age of the masses is over. We are no longer in the First World War, where you take millions of soldiers, give each one a rifle and have them run forward. And the same thing perhaps is happening in the economy. Maybe the biggest question of 21st century economics is what will be the need in the economy for most people in the year 2050.

And once most people are no longer really necessary, for the military and for the economy, the idea that you will continue to have mass medicine is not so certain. Could be. It’s not a prophecy, but you should take very seriously the option that people will lose their military and economic value, and medicine will follow.

{ Edge | Continue reading }

economics, future, neurosciences | January 17th, 2016 12:45 pm

A technique called optogenetics has transformed neuroscience during the past 10 years by allowing researchers to turn specific neurons on and off in experimental animals. By flipping these neural switches, it has provided clues about which brain pathways are involved in diseases like depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder. “Optogenetics is not just a flash in the pan,” says neuroscientist Robert Gereau of Washington University in Saint Louis. “It allows us to do experiments that were not doable before. This is a true game changer like few other techniques in science.” […]

The new technology relies on opsins, a type of ion channel consisting of proteins that conduct neurons’ electrical signaling. Neurons contain hundreds of different types of ion channels but opsins open in response to light. Some opsins are found in the human retina but those used in optogenetics are derived from algae and other organisms. The first opsins used in optogenetics, called channel rhodopsins, open to allow positively charged ions to enter the cell when activated by a flash of blue light, which causes the neuron to fire an electrical impulse. Other opsin proteins pass inhibitory, negatively charged ions in response to light, making it possible to silence neurons as well. […]

The main challenge before optogenetic therapies become a reality is getting opsin genes into the adult human neurons to be targeted in a treatment. In rodents researchers have employed two main strategies: transgenics, in which mice are bred to make opsins in specific neurons—an option unsuitable for use in humans. The other method uses a virus to implant a gene into a neuron. Viruses are currently being used for other types of gene therapy in humans, but challenges remain. Viruses must penetrate mature neurons and deliver their gene cargo without spurring an immune reaction. Then the neuron has to express the opsin in the right place, and it has to go on making the protein continuously—ideally forever.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

neurosciences | January 9th, 2016 1:47 pm

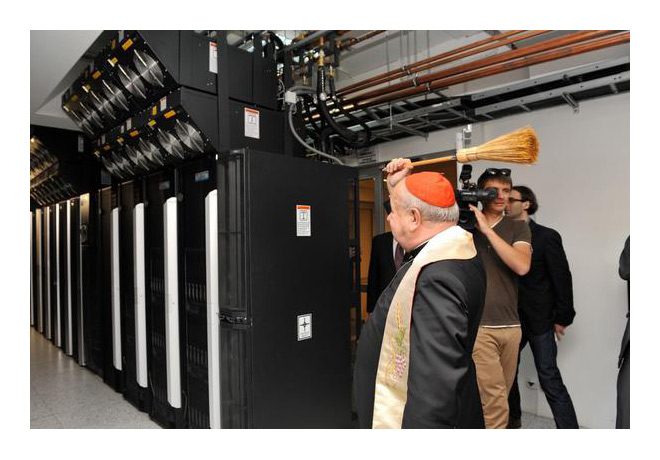

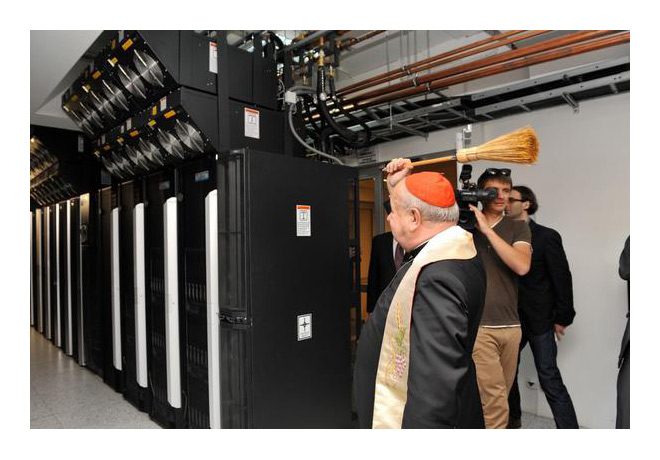

In an unusual new paper, a group of German neuroscientists report that they scanned the brain of a Catholic bishop: Does a bishop pray when he prays? And does his brain distinguish between different religions? […]

Silveira et al. had the bishop perform some religious-themed tasks, but the most interesting result was that there was no detectable difference in brain activity when the bishop was praying, compared to when he was told to do nothing in particular.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

related { How brain architecture leads to abstract thought }

photo { Steven Brahms }

neurosciences | December 17th, 2015 1:45 pm

In 1995, a team of researchers taught pigeons to discriminate between Picasso and Monet paintings. […] After just a few weeks’ training, their pigeons could not only tell a Picasso from a Monet – indicated by pecks on a designated button – but could generalise their learning to discriminate cubist from impressionist works in general. […] For a behaviourist, the moral is that even complex learning is supported by fundamental principles of association, practice and reward. It also shows that you can train a pigeon to tell a Renoir from a Matisse, but that doesn’t mean it knows a lot about art.

[…]

What is now indisputable is that different memories are supported by different anatomical areas of the brain. […] Brain imaging has confirmed the basic division of labour between so-called declarative memory, aka explicit memory (facts and events), and procedural memory, aka implicit memory (habits and skills). The neuroscience allows us to understand the frustrating fact that you have the insight into what you are learning without yet having acquired the skill, or you can have the skill without the insight. In any complex task, you’ll need both. Maybe the next hundred years of the neuroscience of memory will tell us how to coordinate them.

[…]

Chess masters have an amazing memory for patterns on the chess board – able to recall the positions of all the pieces after only a brief glance. Follow-up work showed that they only have this ability if the patterns conform to possible positions in a legal game of chess. When pieces are positioned on the board randomly, however, chess grandmasters have as poor memories as anyone else.

{ The Guardian | Continue reading }

memory | December 15th, 2015 7:14 am

Neurotechnologies are “dual-use” tools, which means that in addition to being employed in medical problem-solving, they could also be applied (or misapplied) for military purposes.

The same brain-scanning machines meant to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease or autism could potentially read someone’s private thoughts. Computer systems attached to brain tissue that allow paralyzed patients to control robotic appendages with thought alone could also be used by a state to direct bionic soldiers or pilot aircraft. And devices designed to aid a deteriorating mind could alternatively be used to implant new memories, or to extinguish existing ones, in allies and enemies alike. […]

In 2005, a team of scientists announced that it had successfully read a human’s mind using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a technique that measures blood flow triggered by brain activity. A research subject, lying still in a full-body scanner, observed a small screen that projected simple visual stimuli—a random sequence of lines oriented in different directions, some vertical, some horizontal, and some diagonal. Each line’s orientation provoked a slightly different flurry of brain functions. Ultimately, just by looking at that activity, the researchers could determine what kind of line the subject was viewing.

It took only six years for this brain-decoding technology to be spectacularly extended—with a touch of Silicon Valley flavor—in a series of experiments at the University of California, Berkeley. In a 2011 study, subjects were asked to watch Hollywood movie trailers inside an fMRI tube; researchers used data drawn from fluxing brain responses to build decoding algorithms unique to each subject. Then, they recorded neural activity as the subjects watched various new film scenes—for instance, a clip in which Steve Martin walks across a room. With each subject’s algorithm, the researchers were later able to reconstruct this very scene based on brain activity alone. The eerie results are not photo-

realistic, but impressionistic: a blurry Steve Martin floats across a surreal, shifting background.

Based on these outcomes, Thomas Naselaris, a neuroscientist at the Medical University of South Carolina and a coauthor of the 2011 study, says, “The potential to do something like mind reading is going to be available sooner rather than later.” More to the point, “It’s going to be possible within our lifetimes.”

{ Foreign Policy | Continue reading }

neurosciences | October 20th, 2015 12:47 pm

My brain tumor introduced itself to me on a grainy MRI, in the summer of 2009, when I was 28 years old. […]

Over time I would lose my memory—almost completely—of things that happened just moments before, and become unable to recall events that happened days and years earlier. […]

Through persistence, luck, and maybe something more, an incredible medical procedure returned my mind and memories to me almost all at once. I became the man who remembered events I had never experienced, due to my amnesia. The man who forgot which member of his family had died while he was sick, only to have that memory, like hundreds of others, come flooding back. The memories came back out of order, with flashbacks mystically presenting themselves in ways that left me both excited and frightened.

{ Quartz | Continue reading }

experience, memory | September 30th, 2015 7:29 am

An influential theory about the malleability of memory comes under scrutiny in a new paper in the Journal of Neuroscience.

The ‘reconsolidation’ hypothesis holds that when a memory is recalled, its molecular trace in the brain becomes plastic. On this view, a reactivated memory has to be ‘saved’ or consolidated all over again in order for it to be stored.

A drug that blocks memory formation (‘amnestic’) will, therefore, not just block new memories but will also cause reactivated memories to be forgotten, by preventing reconsolidation.

This theory has generated a great deal of research interest and has led to speculation that blocking reconsolidation could be used as a tool to ‘wipe’ human memories.

However, Gisquet-Verrier et al. propose that amnestic drugs don’t in fact block reconsolidation, but instead add an additional element to a reactivated memory trace. This additional element is a memory of the amnestic itself – essentially, ‘how it feels’ to be intoxicated with that drug.

In other words, the proposal is that amnestics tag memories with ‘amnestic-intoxication’ which makes these memories less accessible due to the phenomenon of state dependent recall. This predicts that the memories could be retrieved by giving another dose of the amnestic.

So, Gisquet-Verrier et al. are saying that (sometimes) an ‘amnestic’ drug can actually improve memory.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

related { Kids can remember tomorrow what they forgot today }

memory, theory | September 22nd, 2015 2:41 pm

You see a man at the grocery store. Is that the fellow you went to college with or just a guy who looks like him? One tiny spot in the brain has the answer.

Neuroscientists have identified the part of the hippocampus that creates and processes this type of memory, furthering our understanding of how the mind works, and what’s going wrong when it doesn’t.

{ Lunatic Laboratories | Continue reading }

memory, neurosciences | August 19th, 2015 2:08 pm

For decades, many psychologists and neuroscientists have argued that humans have a so-called “cognitive peak.” That is, that a person’s fluid intelligence, or the ability to analyze information and solve problems in novel situations, reaches its apex during early adulthood. But new research done at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Massachusetts General Hospital paints a different picture, suggesting that different aspects of intelligence reach their respective pinnacles at various points over the lifespan—often, many decades later than previously imagined. […]

For example, while short term memory appears to peak at 25 and start to decline at 35, emotional perception peaks nearly two decades later, between 40 and 50. Almost every independent cognitive ability tested appears to have its own age trajectory. The results were reported earlier this year in Psychological Science.

{ The Dana Foundation | Continue reading }

neurosciences | June 1st, 2015 3:01 pm

Ageing causes changes to the brain size, vasculature, and cognition. The brain shrinks with increasing age and there are changes at all levels from molecules to morphology. Incidence of stroke, white matter lesions, and dementia also rise with age, as does level of memory impairment and there are changes in levels of neurotransmitters and hormones. Protective factors that reduce cardiovascular risk, namely regular exercise, a healthy diet, and low to moderate alcohol intake, seem to aid the ageing brain as does increased cognitive effort in the form of education or occupational attainment. A healthy life both physically and mentally may be the best defence against the changes of an ageing brain. Additional measures to prevent cardiovascular disease may also be important. […]

It has been widely found that the volume of the brain and/or its weight declines with age at a rate of around 5% per decade after age 40 with the actual rate of decline possibly increasing with age particularly over age 70. […]

The most widely seen cognitive change associated with ageing is that of memory. Memory function can be broadly divided into four sections, episodic memory, semantic memory, procedural memory, and working memory.18 The first two of these are most important with regard to ageing. Episodic memory is defined as “a form of memory in which information is stored with ‘mental tags’, about where, when and how the information was picked up”. An example of an episodic memory would be a memory of your first day at school, the important meeting you attended last week, or the lesson where you learnt that Paris is the capital of France. Episodic memory performance is thought to decline from middle age onwards. This is particularly true for recall in normal ageing and less so for recognition. It is also a characteristic of the memory loss seen in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). […]

Semantic memory is defined as “memory for meanings”, for example, knowing that Paris is the capital of France, that 10 millimetres make up a centimetre, or that Mozart composed the Magic Flute. Semantic memory increases gradually from middle age to the young elderly but then declines in the very elderly.

{ Postgraduate Medical Journal | Continue reading | Thanks Tim}

brain, health, memory | May 17th, 2015 2:49 pm

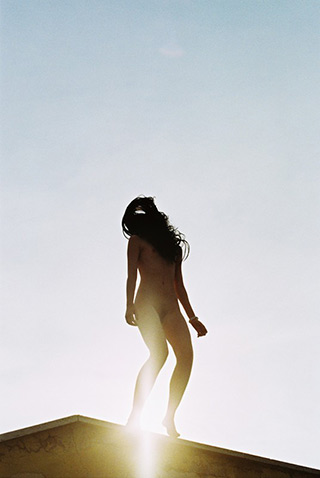

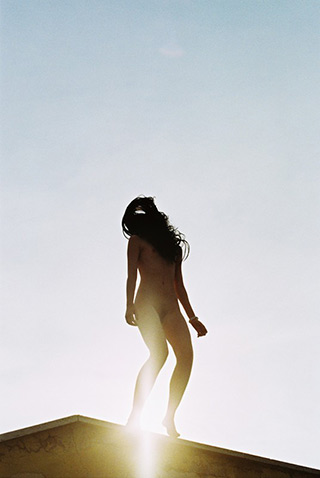

What happens to people when they think they’re invisible?

Using a 3D virtual reality headset, neuroscientists at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm gave participants the sensation that they were invisible, and then examined the psychological effects of apparent invisibility. […] “Having an invisible body seems to have a stress-reducing effect when experiencing socially challenging situations.” […]

“Follow-up studies should also investigate whether the feeling of invisibility affects moral decision-making, to ensure that future invisibility cloaking does not make us lose our sense of right and wrong, which Plato asserted over two millennia ago,” said the report’s co-author, Henrik Ehrsson. […]

In Book II of Plato’s Republic, one of Socrates’s interlocutors tells a story of a shepherd, an ancestor of the ancient Lydian king Gyges, who finds a magic ring that makes the wearer invisible. The power quickly corrupts him, and he becomes a tyrant.

The premise behind the story of the Ring of Gyges, which inspired HG Wells’s seminal 1897 science fiction novel, The Invisible Man, is that we behave morally so that we can be seen doing so.

{ CS Monitor | Continue reading }

photo { Ren Hang }

ideas, neurosciences | April 24th, 2015 1:59 pm

Back in 2009, researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara performed a curious experiment. In many ways, it was routine — they placed a subject in the brain scanner, displayed some images, and monitored how the subject’s brain responded. The measured brain activity showed up on the scans as red hot spots, like many other neuroimaging studies.

Except that this time, the subject was an Atlantic salmon, and it was dead.

Dead fish do not normally exhibit any kind of brain activity, of course. The study was a tongue-in-cheek reminder of the problems with brain scanning studies. Those colorful images of the human brain found in virtually all news media may have captivated the imagination of the public, but they have also been subject of controversy among scientists over the past decade or so. In fact, neuro-imagers are now debating how reliable brain scanning studies actually are, and are still mostly in the dark about exactly what it means when they see some part of the brain “light up.”

{ Neurophilosophy | Continue reading }

neurosciences | April 10th, 2015 11:26 am

Recalling one memory actually leads to the forgetting of other competing memories, a new study confirms.

It is one of the single most surprising facts about memory, now isolated by neuroscience research.

Although many scientists believed the brain must work this way, this is the first time it has been demonstrated.

{ PsyBlog | Continue reading | Nature }

memory | April 3rd, 2015 11:40 am

15 years ago, the neurosciences defined the main function of brains in terms of processing input to compute output: “brain function is ultimately best understood in terms of input/output transformations and how they are produced” wrote Mike Mauk in 2000.

Since then, a lot of things have been discovered that make this stimulus-response concept untenable and potentially based largely on laboratory artifacts.

For instance, it was discovered that the likely ancestral state of behavioral organization is one of probing the environment with ongoing, variable actions first and evaluating sensory feedback later (i.e., the inverse of stimulus response). […]

In humans, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies over the last decade and a half revealed that the human brain is far from passively waiting for stimuli, but rather constantly produces ongoing, variable activity, and just shifts this activity over to other networks when we move from rest to task or switch between tasks.

{ Björn Brembs | Continue reading }

neurosciences, theory | March 27th, 2015 12:30 pm