neurosciences

Scientists are increasingly convinced that the vast assemblage of microfauna in our intestines may have a major impact on our state of mind. The gut-brain axis seems to be bidirectional—the brain acts on gastrointestinal and immune functions that help to shape the gut’s microbial makeup, and gut microbes make neuroactive compounds, including neurotransmitters and metabolites that also act on the brain. […]

Microbes may have their own evolutionary reasons for communicating with the brain. They need us to be social, says John Cryan, a neuroscientist at University College Cork in Ireland, so that they can spread through the human population. Cryan’s research shows that when bred in sterile conditions, germ-free mice lacking in intestinal microbes also lack an ability to recognize other mice with whom they interact. In other studies, disruptions of the microbiome induced mice behavior that mimics human anxiety, depression and even autism. In some cases, scientists restored more normal behavior by treating their test subjects with certain strains of benign bacteria. Nearly all the data so far are limited to mice, but Cryan believes the findings provide fertile ground for developing analogous compounds, which he calls psychobiotics, for humans. “That dietary treatments could be used as either adjunct or sole therapy for mood disorders is not beyond the realm of possibility,” he says.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

related { Is Neuroscience Based On Biology? }

brain, food, drinks, restaurants, neurosciences | March 10th, 2015 1:05 pm

The scientific study of heartbreak is extremely new, with nearly all articles on the matter appearing in the last 10-15 years. In fact, the notion that strong emotional stress can impact health was not widely accepted in academia until recently.

In the 1990’s, Japan started accruing cases of a disease called “takotsubo cardiomyopathy,” where patients’ hearts would actually become damaged and their ventricles would be misshapen (into that of a “takotsubo,” or octopus-catching pot – a very bad shape for a heart chamber). Curiously, these cases were not heart attacks, but instead were a form of heart failure brought on by a rush of stress hormones.

After 15 years, the syndrome was finally mentioned in a 2005 New England Journal of Medicine article, where it was renamed “Broken Heart Syndrome.” Among the causes of Broken Heart Syndrome are romantic rejection, divorce, or the death of a loved one, and the outcome can be as serious as death.

{ NeuWrite | Continue reading }

neurosciences, psychology, relationships | February 14th, 2015 4:11 pm

“The goal of memory isn’t to keep the details. It’s to be able to generalize from what you know so that you are more confident in acting on it,” Davachi says.

You run away from the dog that looks like the one that bit you, rather than standing around questioning how accurate your recall is.

{ The New Yorker | Continue reading }

memory | February 9th, 2015 12:59 pm

Few studies have investigated the role of sleep deprivation in the formation of false memories, despite overwhelming evidence that sleep deprivation impairs cognitive function. We examined the relationship between self-reported sleep duration and false memories and the effect of 24 hr of total sleep deprivation on susceptibility to false memories. We found that under certain conditions, sleep deprivation can increase the risk of developing false memories.

{ Neuroethics & Law | Continue reading }

acrylic on canvas { William Betts, Amber, 03/19/04, 20:05:12, 2008 }

memory, sleep | February 5th, 2015 1:40 pm

A car accident, the loss of a loved one and financial trouble are just a few of the myriad stressors we may encounter in our lifetimes. Some of us take it in stride, while others go on to develop anxiety or depression. How well will we deal with the inevitable lows of life?

A clue to this answer, according to a new Duke University study, is found in an almond-shaped structure deep within our brains: the amygdala. By measuring activity of this area, which is crucial for detecting and responding to danger, researchers say they can tell who will become depressed or anxious in response to stressful life events, as far as four years down the road.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

brain, neurosciences | February 5th, 2015 1:40 pm

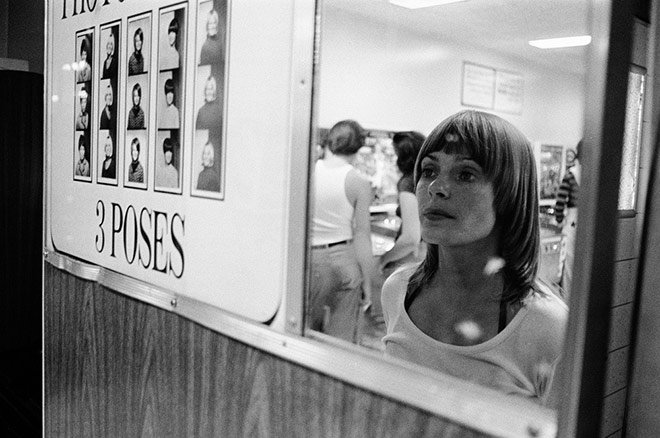

Memory has to be ‘turned on’ in order to remember even the simplest details, a new study finds. When not expecting to be tested, people can forget information just one second after paying attention to it. But, when they expect to be tested, people’s recall is doubled or even tripled.

{ PsyBlog | Continue reading }

photo { Spot | NYT }

guide, memory | January 30th, 2015 3:47 am

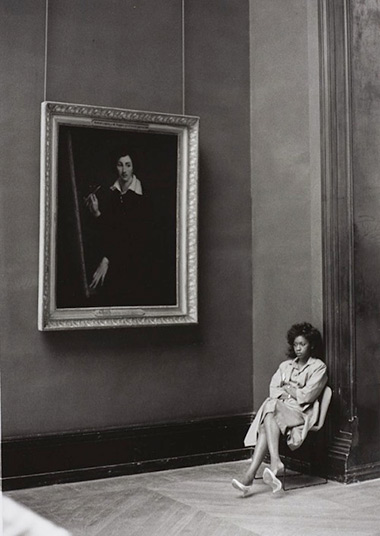

We’ve all had that experience of going purposefully from one room to another, only to get there and forget why we made the journey. Four years ago, researcher Gabriel Radvansky and his colleagues stripped this effect down, showing that the simple act of passing through a doorway induces forgetting.

Now psychologists at Knox College, USA, have taken things further, demonstrating that merely imagining walking through a doorway is enough to trigger increased forgetfulness.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

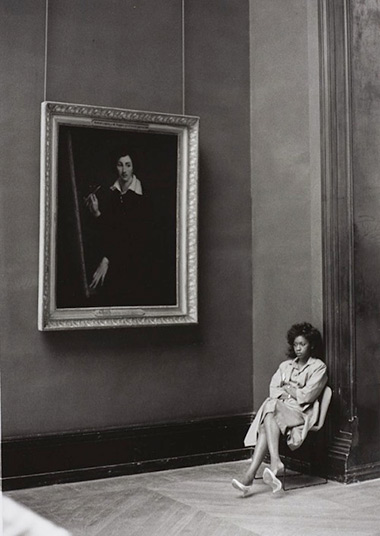

photo { Barbara Klemm, Louvre, Paris, 1987 }

memory | January 15th, 2015 3:55 pm

In an experiment researchers showed that the human brain uses memories to make predictions about what it expects to find in familiar contexts. When those subconscious predictions are shown to be wrong, the related memories are weakened and are more likely to be forgotten. And the greater the error, the more likely you are to forget the memory.

{ Lunatic Laboratories | Continue reading }

memory | January 10th, 2015 11:56 am

Ghost illusion created in the lab

On June 29, 1970, mountaineer Reinhold Messner had an unusual experience. Recounting his descent down the virgin summit of Nanga Parbat with his brother, freezing, exhausted, and oxygen-starved in the vast barren landscape, he recalls, “Suddenly there was a third climber with us… a little to my right, a few steps behind me, just outside my field of vision.”

It was invisible, but there. Stories like this have been reported countless times by mountaineers, explorers, and survivors, as well as by people who have been widowed, but also by patients suffering from neurological or psychiatric disorders. They commonly describe a presence that is felt but unseen, akin to a guardian angel or a demon. Inexplicable, illusory, and persistent.

Olaf Blanke’s research team at EPFL has now unveiled this ghost. The team was able to recreate the illusion of a similar presence in the laboratory and provide a simple explanation. They showed that the “feeling of a presence” actually results from an alteration of sensorimotor brain signals, which are involved in generating self-awareness by integrating information from our movements and our body’s position in space.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading | more }

neurosciences | November 6th, 2014 1:57 pm

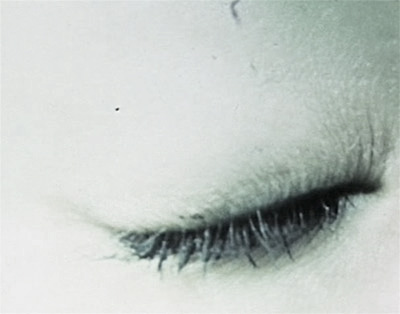

We assume that we can see the world around us in sharp detail. In fact, our eyes can only process a fraction of our surroundings precisely. In a series of experiments, psychologists at Bielefeld University have been investigating how the brain fools us into believing that we see in sharp detail. The results have been published in the scientific magazine ‘Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.’ Its central finding is that our nervous system uses past visual experiences to predict how blurred objects would look in sharp detail.

{ Universität Bielefeld | Continue reading }

related { Scientists have found “hidden” brain activity that can indicate if a vegetative patient is aware }

eyes, neurosciences | October 17th, 2014 12:17 pm

In December last year, researchers Brian Dias and Kerry Ressler made a splash with a paper seeming to show that memories can be inherited.

This article, published in Nature Neuroscience, reported that if adult mice are taught to be afraid of a particular smell, then their children will also fear it. Which is pretty wild. Epigenetics was proposed as the mechanism.

Now, however, psychologist Gregory Francis says that the data Dias and Ressler published are just too good to be true.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

genes, memory | October 16th, 2014 3:17 pm

Have you ever felt lost and alone? If so, this experience probably involved your hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure in the middle of the brain. About 40 years ago, scientists with electrodes discovered that some neurons in the hippocampus fire each time an animal passes through a particular location in its environment. These neurons, called place cells, are thought to function as a cognitive map that enables navigation and spatial memory.

Place cells are typically studied by recording from the hippocampus of a rodent navigating through a laboratory maze. But in the real world, rats can cover a lot of ground. For example, many rats leave their filthy sewer bunkers every night to enter the cozy bedrooms of innocent sleeping children.

In a recent paper, esteemed neuroscientist Dr. Dylan Rich and colleagues investigated how place cells encode very large spaces. Specifically, they asked: how are new place cells recruited to the network as a rat explores a truly giant maze?

{ Sick papes | Continue reading }

brain, neurosciences | October 7th, 2014 6:03 am

We will review evidence from neuroscience, complex network research and evolution theory and demonstrate that — at least in terms of psychopharmacological intervention — on the basis of our understanding of brain function it seems inconceivable that there ever will be a drug that has the desired effect without undesirable side effects.

{ Neuroethics | Continue reading }

photo { Hannes Caspar }

drugs, neurosciences | October 2nd, 2014 12:56 pm

Some people can handle stressful situations better than others, and it’s not all in their genes: Even identical twins show differences in how they respond.

Researchers have identified a specific electrical pattern in the brains of genetically identical mice that predicts how well individual animals will fare in stressful situations.

The findings may eventually help researchers prevent potential consequences of chronic stress — such as post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and other psychiatric disorders — in people who are prone to these problems.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

neurosciences | August 1st, 2014 9:09 am

Everybody knows that men are women have some biological differences – different sizes of brains and different hormones. It wouldn’t be too surprising if there were some neurological differences too. The thing is, we also know that we treat men and women differently from the moment they’re born, in almost all areas of life. Brains respond to the demands we make of them, and men and women have different demands placed on them. […]

They report finding significant differences between the sexes, but don’t show the statistics that allow the reader to evaluate the size of any sex difference against other factors such as age or individual variability. […] A significant sex difference could be tiny compared to the differences between people of different ages, or compared to the normal differences between individuals.

{ The Conversation | Continue reading }

The most important thing to take from this research is – as the authors report – increasing gender equality disproportionately benefits women. This is because – no surprise! – gender inequality disproportionately disadvantages women. […] But the provocative suggestion of this study is that as societies develop we won’t necessarily see all gender differences go away. Some cognitive differences may actually increase when women are at less of a disadvantage.

{ Mind Hacks | Continue reading }

genders, neurosciences, psychology | July 30th, 2014 2:46 pm

“I looked up at the shower head, and it was as if the water droplets had stopped in mid-air” […]

Although Baker is perhaps the most dramatic case, a smattering of strikingly similar accounts can be found, intermittently, in medical literature. There are reports of time speeding up – so called “zeitraffer” phenomenon – and also more fragmentary experiences called “akinetopsia”, in which motion momentarily stops.

For instance, travelling home one day, one 61-year-old woman reported that the movement of the closing train doors, and fellow passengers, was in slow motion and “broken up”, as if in “freeze frames”. A 58-year-old Japanese man, meanwhile, seemed to be experiencing life like a badly dubbed movie; in conversation, he found that although others’ voices sounded normal, they were out of sync with their faces. […]

One explanation for this double-failure is that our motion perception system has its own stopwatch, recording how fast things are moving across our vision – and when this is disrupted by brain injury, the world stands still. For Baker, stepping into the shower might have exacerbated the problem, since the warm water would have drawn the blood away from the brain to the extremities of the body, further disturbing the brain’s processing.

Another explanation comes from the discovery that our brain records its perceptions in discrete “snapshots”, like the frames of a film reel. “The healthy brain reconstructs the experience and glues together the different frames,” says Rufin VanRullen at the French Centre for Brain and Cognition Research in Toulouse, “but if brain damage destroys the glue, you might only see the snapshots.”

{ BBC | Continue reading }

neurosciences, time | June 30th, 2014 7:11 am

It’s a question that has plagued philosophers and scientists for thousands of years: Is free will an illusion?

Now, a new study suggests that free will may arise from a hidden signal buried in the “background noise” of chaotic electrical activity in the brain, and that this activity occurs almost a second before people consciously decide to do something. […]

Experiments performed in the 1970s also raised doubts about human volition. Those studies, conducted by the late neuroscientist Benjamin Libet, revealed that the region of the brain that plans and executes movement, called the motor cortex, fired prior to people’s decision to press a button, suggesting this part of the brain “makes up its mind” before peoples’ conscious decision making kicks in.

To understand more about conscious decision making, Bengson’s team used electroencephalography (EEG) to measure the brain waves of 19 undergraduates as they looked at a screen and were cued to make a random decision about whether to look right or left.

When people made their decision, a characteristic signal registered that choice as a wave of electrical activity that spread across specific brain regions.

But in a fascinating twist, other electrical activity emanating from the back of the head predicted people’s decisions up to 800 milliseconds before the signature of conscious decision making emerged.

{ Live Science | Continue reading }

related { Searching for the “Free Will” Neuron }

ideas, neurosciences | June 24th, 2014 3:49 am

Some people report that in fear-related situations time seems to slowdown. That is to say, for example, during a car crash the event takes much longer from the point of a person experiencing the crash than the observer. But how and why the brain creates this slow motion experience is not completely understood. […]

In a situation where emotions are involved, there is an increased amygdala activity and a consequent increase in memory recording. When a person is asked to recall a fear-related event, the amount of details that he/she can recall is substantially increased compared to normal situation. However, the brain, not used to recalling so many details, is left to think that the event must have taken longer than it really did.

It is ‘the trick of memory’ as Eagleman puts it; the brain is not used to these exceptional circumstances and therefore, it tricks itself into false time perception.

{ The Question Gene | Continue reading }

memory | June 9th, 2014 6:09 am

Those parents at the park taking all those photos are actually paying less attention to the moment, she says, because they’re focused on the act of taking the photo.

“Then they’ve got a thousand photos, and then they just dump the photos somewhere and don’t really look at them very much, ’cause it’s too difficult to tag them and organize them,” says Maryanne Garry, a psychology professor at the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand. […]

Henkel, who researches human memory at Fairfield University in Connecticut, found what she called a “photo-taking impairment effect.”

“The objects that they had taken photos of — they actually remembered fewer of them, and remembered fewer details about those objects. Like, how was this statue’s hands positioned, or what was this statue wearing on its head. They remembered fewer of the details if they took photos of them, rather than if they had just looked at them,” she says.

Henkel says her students’ memories were impaired because relying on an external memory aid means you subconsciously count on the camera to remember the details for you.

{ NPR | Continue reading }

photo { Florian Maier-Aichen, Untitled (Cloud), 2001 }

memory, photogs | June 1st, 2014 6:38 am

Important peculiarities of the human memory system:

— A remarkable capacity for storing information is coupled with a highly fallible retrieval process.

— What is accessible in memory is highly dependent on the current environmental, interpersonal, emotional and body-state cues.

— Retrieving information from memory is a dynamic process that alters the subsequent state of the system.

— Access to competing memory representations regresses towards the earlier representation over time.

{ Robert Bjork | Continue reading }

memory | May 25th, 2014 12:01 pm