neurosciences

The question is, what happens to your ideas about computational architecture when you think of individual neurons not as dutiful slaves or as simple machines but as agents that have to be kept in line and that have to be properly rewarded and that can form coalitions and cabals and organizations and alliances? This vision of the brain as a sort of social arena of politically warring forces seems like sort of an amusing fantasy at first, but is now becoming something that I take more and more seriously, and it’s fed by a lot of different currents.

Evolutionary biologist David Haig has some lovely papers on intrapersonal conflicts where he’s talking about how even at the level of the genetics, even at the level of the conflict between the genes you get from your mother and the genes you get from your father, the so-called madumnal and padumnal genes, those are in opponent relations and if they get out of whack, serious imbalances can happen that show up as particular psychological anomalies.

We’re beginning to come to grips with the idea that your brain is not this well-organized hierarchical control system where everything is in order, a very dramatic vision of bureaucracy. In fact, it’s much more like anarchy with some elements of democracy. Sometimes you can achieve stability and mutual aid and a sort of calm united front, and then everything is hunky-dory, but then it’s always possible for things to get out of whack and for one alliance or another to gain control, and then you get obsessions and delusions and so forth.

You begin to think about the normal well-tempered mind, in effect, the well-organized mind, as an achievement, not as the base state, something that is only achieved when all is going well, but still, in the general realm of humanity, most of us are pretty well put together most of the time. This gives a very different vision of what the architecture is like, and I’m just trying to get my head around how to think about that.

{ Daniel C. Dennett/Edge | Continue reading }

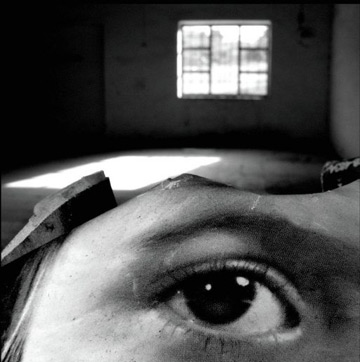

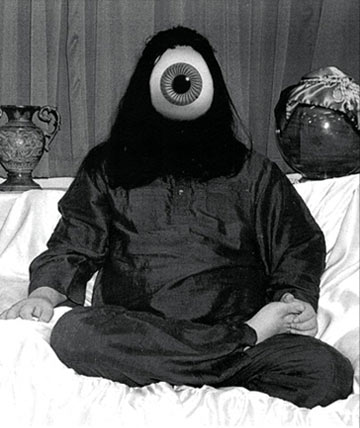

photo { Robert Heinecken }

brain, neurosciences, photogs | January 18th, 2013 9:36 am

What is memory for? Episodic memory enables one to capture the precise details of an experience, and then to recollect this information rapidly whenever and wherever needed. Typical examples of its evolutionary value focus on the individual navigating the world, but the advantages conferred by episodic memory may be more far-reaching than often appreciated. For example, interactions with other people are important for our survival and wellbeing. Might episodic memory be crucial for establishing and/or maintaining interpersonal relationships? To address this question, we examined social relationships in three amnesic patients.

{ Frontiers | Continue reading }

memory, relationships | January 16th, 2013 3:06 pm

As we age, it just may be the ability to filter and eliminate old information – rather than take in the new stuff - that makes it harder to learn, scientists report.

“When you are young, your brain is able to strengthen certain connections and weaken certain connections to make new memories,” said Dr. Joe Z. Tsien, neuroscientist. It’s that critical weakening that appears hampered in the older brain, according to a study in the journal Scientific Reports. […]

“We know we lose the ability to perfectly speak a foreign language if we learn than language after the onset of sexual maturity. I can learn English but my Chinese accent is very difficult to get rid of. The question is why,” Tsien said.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

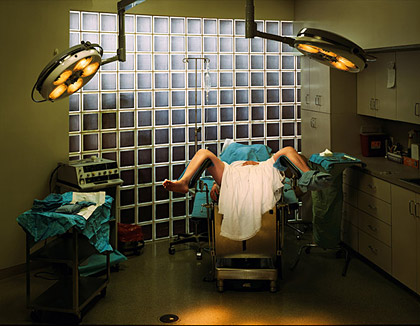

photo { Achim Lippoth }

memory | January 10th, 2013 4:02 am

A few months ago I wrote a two-part post about how fMRI and PET scan technology were able to detect differences in the brains of psychopaths compared to non-psychopathic individuals. This area of research has identified that psychopathy has a genetic component, and has even been used in court cases to determine sentencing.

Recently, I came across a story on NPR about a neuroscientist who studies these scans, and decided to analyze his own brain scans and those of his family to determine if psychopathy was present. What he found was more than a little disturbing to him…

James Fallon reported that there was a documented history of criminal activity on his paternal side of the family, (including a relation to Lizzy Borden), that made him curious to view the brain scans of his family. They had all previously submitted brain scans and a blood sample in order to rule out a risk for Alzheimer’s, so he had the materials already. […] Fallon decided to go one step further and analyze the blood samples in search of genes that are associated with violence; namely the MAO-A gene (monoamine oxidase A), specifically MAOA-L (low activity variant). […] Much to his dismay, Fallon again found that everyone in his family has the low-aggression variant of the MAO-A gene, except for one person—himself.

Fallon isn’t, of course, a killer; however, genetically speaking he meets the criteria of psychopathy. […] And therein lays the process of how one person can become a psychopath, and another to go on with a fairly “normal” life.

{ Forensic Focus | Continue reading }

photo { Leon Levinstein, Fifth Avenue, 1959 }

neurosciences | January 2nd, 2013 10:04 am

We have past, present and future; we can imagine various time relationships such as imagining some time in the future from the prospective of looking back at it from even further into the future. But we can also abandon identifying a particular time when we imagine. For example we can simulate what it would be like to be in another’s shoes or what it would be like to be in a different place. Instead of time-traveling, we can space-travel or identity-travel. It seems that the evidence so far implies that future and atemporal imagined events are represented similarly. But there are differences between temporal and atemporal imaginings.

{ thoughts on thoughts | Continue reading }

neurosciences, time | December 14th, 2012 2:00 am

For thousands of years, a core pursuit of medical science has been the careful observation of physical symptoms and signs. Through these observations, supplemented more recently by investigative techniques, an understanding of how symptoms and signs are generated by disease has developed. However, there is a group of patients with symptoms and signs that, from the earliest medical records to the present day, elude a diagnosis with a typical ‘organic’ disease. This is not simply because of an absence of pathology after sufficient investigation, rather that symptoms themselves are inconsistent with those occurring in typical disease. In times past, these symptoms were said to be ‘hysterical’, a term now replaced by the less pejorative but no more enlightening labels: ‘medically unexplained’, ‘psychogenic’, ‘conversion’, ‘non-organic’ and ‘functional’.

There are numerous historical examples of patients identified as having hysteria who would now be diagnosed with an organic medical disorder. Some have assumed that this process of salvaging patients from (mis)diagnosis with hysteria would continue inexorably until a ‘proper’ medical diagnosis was achieved. Slater (1965), in his influential paper on the topic, described the diagnosis of hysteria as ‘a disguise for ignorance and a fertile source of clinical error’. In other words, with increasing medical knowledge, all patients would be rescued from a diagnostic category that did little more than assert that they were ‘too difficult’.

This has not come to pass (Stone et al., 2005). Recent epidemiological work has demonstrated that neurologists continue to diagnose a ‘non-organic’ disorder in ∼16% of their patients, making this the second most common diagnosis of neurological outpatients.

{ Brain/Oxford Journals | Continue reading }

photo { Paul Himmel }

health, neurosciences, psychology | December 5th, 2012 3:17 pm

This was terrible news for neuroscience—if six studies led to six different answers, why should anybody believe anything that neuroscientists had to say? […] And then, surprisingly, the field prospered. Brain imaging became more, not less, popular. The technique of PET was replaced with the more flexible technique of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which allowed scientists to study people’s brains without the use of the risky radioactive tracers, and to conduct longer studies that collected more data and yielded more reliable results. […]

After two decades of almost complete dominance, a few bright souls started speaking up, asking: Are all these brain studies really telling us much as we think they are?

{ The New Yorker | Continue reading }

related { Neuroscience Team Explains Why Old People Get Scammed }

neurosciences | December 4th, 2012 6:00 am

Inattentional blindness-the failure to see visible and otherwise salient events when one is paying attention to something else-has been proposed as an explanation for various real-world events. In one such event, a Boston police officer chasing a suspect ran past a brutal assault and was prosecuted for perjury when he claimed not to have seen it. However, there have been no experimental studies of inattentional blindness in real-world conditions. We simulated the Boston incident by having subjects run after a confederate along a route near which three other confederates staged a fight. At night only 35% of subjects noticed the fight; during the day 56% noticed. We manipulated the attentional load on the subjects and found that increasing the load significantly decreased noticing. These results provide evidence that inattentional blindness can occur during real-world situations, including the Boston case.

{ i-Perception | PDF }

eyes, neurosciences | November 14th, 2012 3:27 pm

Today, the near 10-year-old Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture believes that neuroscience could make science’s greatest contribution to the field of architecture since physics informed fundamental structural methods, acoustic designs, and lighting calculations in the late 19th century. […]

With today’s sophisticated brain-imaging techniques, neuroscientists can examine how the brain processes environments, even with the complex limitations of, say, someone who’s blind, or autistic, or has dementia. […]

Macagno has been testing hospital design in a virtual-reality lab, and this work could bring us closer to that elusive hospital where, for example, no one gets lost. Other findings from the kind of research he is talking about may challenge what architects have practiced for years. For instance, hospital rooms for premature babies were long built to accommodate their medical equipment and caregivers, not to promote the development of the newborns’ brains. Neuroscience research tells us that the constant noise and harsh lighting of such environments can interfere with the early development of a baby’s visual and auditory systems.

{ Pacific Standard | Continue reading }

architecture, neurosciences | November 13th, 2012 11:34 am

Many children spontaneously report memories of ‘past lives’. For believers, this is evidence for reincarnation; for others, it’s a psychological oddity. But what happens when they grow up?

Icelandic psychologists Haraldsson and Abu-Izzedin looked into it. They took 28 adults, members of the Druze community of Lebanon. They’d all been interviewed about past life memories by the famous reincarnationist Professor Ian Stephenson in the 70s, back when they were just 3-9 years old. Did they still ‘remember’? […]

As children they reported on average 30 distinct memories of past lives. As adults they could only remember 8, but of those, only half matched the ones they’d talked about previously.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

photo { Taryn Simon }

kids, memory | November 7th, 2012 11:31 am

New research shows a simple reason why even the most intelligent, complex brains can be taken by a swindler’s story – one that upon a second look offers clues it was false.

When the brain fires up the network of neurons that allows us to empathize, it suppresses the network used for analysis, a pivotal study led by a Case Western Reserve University researcher shows. […]

When the analytic network is engaged, our ability to appreciate the human cost of our action is repressed.

At rest, our brains cycle between the social and analytical networks. But when presented with a task, healthy adults engage the appropriate neural pathway, the researchers found.

The study shows for the first time that we have a built-in neural constraint on our ability to be both empathetic and analytic at the same time.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Jonathan Waiter }

neurosciences, relationships | October 30th, 2012 4:08 pm

In the summer of 2008, police arrived at a caravan in the seaside town of Aberporth, west Wales, to arrest Brian Thomas for the murder of his wife. The night before, in a vivid nightmare, Thomas believed he was fighting off an intruder in the caravan – perhaps one of the kids who had been disturbing his sleep by revving motorbikes outside. Instead, he was gradually strangling his wife to death. When he awoke, he made a 999 call, telling the operator he was stunned and horrified by what had happened, and unaware of having committed murder.

Crimes committed by sleeping individuals are mercifully rare. Yet they provide striking examples of the unnerving potential of the human unconscious. In turn, they illuminate how an emerging science of consciousness is poised to have a deep impact upon concepts of responsibility that are central to today’s legal system.

After a short trial, the prosecution withdrew the case against Thomas. Expert witnesses agreed that he suffered from a sleep disorder known as pavor nocturnus, or night terrors, which affects around one per cent of adults and six per cent of children.

[…]

It is commonplace to drive a car for long periods without paying much attention to steering or changing gear. According to Jonathan Schooler, professor of psychology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, ‘we are often startled by the discovery that our minds have wandered away from the situation at hand’. But if I am unconscious of my actions when I zone out, to what degree is it really ‘me’ doing the driving?

This question takes on a more urgent note when the lives of others are at stake. […] The driver appeared in Worcester Crown Court on charges of causing death by reckless driving. For the defence, a psychologist described to the court that ‘driving without awareness’ might occur following long, monotonous periods at the wheel. The jury was sufficiently convinced of his lack of conscious control to acquit on the basis of automatism.

The argument for a lack of consciousness here is much less straightforward than for someone who is asleep. In fact, the Court of Appeal said that the defence of automatism should not have been on the table in the first place, because a driver without ‘awareness’ still retains some control of the car. None the less, the grey area between being in control and aware on the one hand, and in control and unaware on the other, is clearly crucial for a legal notion of voluntary action.

If we accept automatism then we reduce the conscious individual to an unconscious machine. However, we should remember that all acts, whether consciously thought-out or reflexive and automatic, are the product of neural mechanisms.

{ aeon | Continue reading }

previously { Sometime after 2 A.M. one Sunday morning in May 1987, Kenneth James Parks drove 23 kilometers to the apartment of his wife’s parents. }

photo { Claudine Doury }

incidents, law, neurosciences | October 25th, 2012 6:27 am

Neuroscientists from New York University and the University of California, Irvine have isolated the “when” and “where” of molecular activity that occurs in the formation of short-, intermediate-, and long-term memories. Their findings, which appear in the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, offer new insights into the molecular architecture of memory formation and, with it, a better roadmap for developing therapeutic interventions for related afflictions.

{ NYU | Continue reading }

brain, memory | October 16th, 2012 6:33 am

Once upon a time, a neurosurgeon named Eben Alexander contracted a bad case of bacterial meningitis and fell into a coma. While immobile in his hospital bed, he experienced visions of such intense beauty that they changed everything. […] Our current understanding of the mind “now lies broken at our feet”—for, as the doctor writes, “What happened to me destroyed it, and I intend to spend the rest of my life investigating the true nature of consciousness.” […]

Well, I intend to spend the rest of the morning sparing him the effort. […]

Everything—absolutely everything—in Alexander’s account rests on repeated assertions that his visions of heaven occurred while his cerebral cortex was “shut down,” “inactivated,” “completely shut down,” “totally offline,” and “stunned to complete inactivity.” The evidence he provides for this claim is not only inadequate—it suggests that he doesn’t know anything about the relevant brain science.

{ Sam Harris | Continue reading }

related { Have you ever noticed that more people come back from Heaven than from Hell? }

photo { Henry Peach Robinson, Fading Away, 1858 | more: Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop at the Metropolitan Museum of Art }

neurosciences, photogs | October 15th, 2012 8:58 am

The idea that humans walk in circles is no urban myth. This was confirmed by Jan Souman and colleagues in a 2009 study, in which participants walked for hours at night in a German forest and the Tunisian Sahara. […]

Souman’s team rejected past theories, including the idea that people have one leg that’s stronger or longer than the other. If that were true you’d expect people to systematically veer off in the same direction, but their participants varied in their circling direction.

Now a team in France has made a bold attempt to get to the bottom of the mystery. […] [It] suggests that our propensity to walk in circles is related in some way to slight irregularities in the vestibular system. Located in inner ear, the vestibular system guides our balance and minor disturbances here could skew our sense of the direction of “straight ahead” just enough to make us go around in circles.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

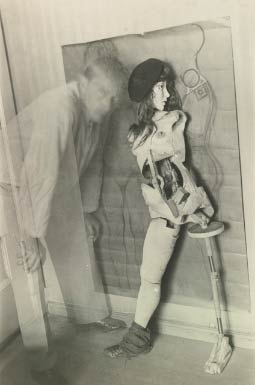

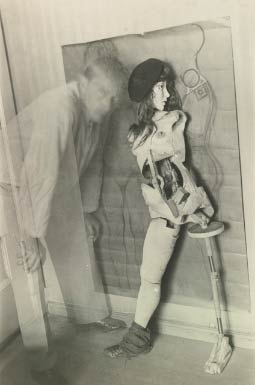

photo { Hans Bellmer }

brain, neurosciences, photogs | October 4th, 2012 5:59 am

Canadian researchers have come up with a new, precise definition of boredom based on the mental processes that underlie the condition.

Although many people may see boredom as trivial and temporary, it actually is linked to a range of psychological, social and health problems, says Guelph psychology professor Mark Fenske. […]

After reviewing existing psychological science and neuroscience studies, they defined boredom as “an aversive state of wanting, but being unable, to engage in satisfying activity,” which arises from failures in one of the brain’s attention networks.

In other words, you become bored when:

• you have difficulty paying attention to the internal information, such as thoughts or feelings, or outside stimuli required to take part in satisfying activity;

• you are aware that you’re having difficulty paying attention; and

• you blame the environment for your sorry state (“This task is boring”; “There is nothing to do”).

{ University of Guelph | Continue reading }

art { Picasso, Femme couchée lisant, 1960 }

Linguistics, neurosciences, psychology | October 1st, 2012 12:59 pm

Deisseroth is developing a remarkable way to switch brain cells off and on by exposing them to targeted green, yellow, or blue flashes. With that ability, he is learning how to regulate the flow of information in the brain.

Deisseroth’s technique, known broadly as optogenetics, could bring new hope to his most desperate patients. In a series of provocative experiments, he has already cured the symptoms of psychiatric disease in mice. Optogenetics also shows promise for defeating drug addiction. […]

For all its complexity, the brain in some ways is a surprisingly simple device. Neurons switch off and on, causing signals to stop or go. Using optogenetics, Deisseroth can do that switching himself. He inserts light-sensitive proteins into brain cells. Those proteins let him turn a set of cells on or off just by shining the right kind of laser beam at the cells.

That in turn makes it possible to highlight the exact neural pathways involved in the various forms of psychiatric disease. A disruption of one particular pathway, for instance, might cause anxiety.

{ Discover | Continue reading }

brain, health, neurosciences, science, technology | September 27th, 2012 12:43 pm

The 2012 Ig Nobel Prize Winners

PSYCHOLOGY PRIZE: Anita Eerland and Rolf Zwaan [THE NETHERLANDS] and Tulio Guadalupe [PERU, RUSSIA, and THE NETHERLANDS] for their study “Leaning to the Left Makes the Eiffel Tower Seem Smaller.”

[…]

PEACE PRIZE: The SKN Company [RUSSIA], for converting old Russian ammunition into new diamonds.

NEUROSCIENCE PRIZE: Craig Bennett, Abigail Baird, Michael Miller, and George Wolford [USA], for demonstrating that brain researchers, by using complicated instruments and simple statistics, can see meaningful brain activity anywhere — even in a dead salmon.

{ Improbable Research | Continue reading }

haha, neurosciences, psychology, science | September 25th, 2012 1:43 pm

For people with a condition that some scientists call misophonia, mealtime can be torture. The sounds of other people eating — chewing, chomping, slurping, gurgling — can send them into an instantaneous, blood-boiling rage. […]

Many people can be driven to distraction by certain small sounds that do not seem to bother others — gum chewing, footsteps, humming. But sufferers of misophonia, a newly recognized condition that remains little studied and poorly understood, take the problem to a higher level.

They also follow a strikingly consistent pattern, experts say. The condition almost always begins in late childhood or early adolescence and worsens over time, often expanding to include more trigger sounds, usually those of eating and breathing. […]

Aage R. Moller, a neuroscientist at the University of Texas at Dallas […] believes the condition is hard-wired, like right- or left-handedness, and is probably not an auditory disorder but a “physiological abnormality” that resides in brain structures activated by processed sound. […]

Taylor Benson, a 19-year-old sophomore at Creighton University in Omaha, says many mouth noises, along with sniffling and gum chewing, make her chest tighten and her heart pound. She finds herself clenching her fists and glaring at the person making the sound.

“This condition has caused me to lose friends and has caused numerous fights,” she said.

Misophonia (“dislike of sound”) is sometimes confused with hyperacusis, in which sound is perceived as abnormally loud or physically painful. But Dr. Johnson says they are not the same. “These people like sound, the louder the better,” she said of misophonia patients. “The sounds they object to are soft, hardly audible sounds.” One patient is driven crazy by her beloved dog licking its paws. Another can’t bear the pop of the plosive “p” in ordinary conversation.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

health, neurosciences, noise and signals | September 23rd, 2012 2:50 pm

Newly formed emotional memories can be erased from the human brain. This is shown by researchers from Uppsala University in a new study now being published by the academic journal Science. The findings may represent a breakthrough in research on memory and fear. […]

When a person learns something, a lasting long-term memory is created with the aid of a process of consolidation, which is based on the formation of proteins. When we remember something, the memory becomes unstable for a while and is then restabilized by another consolidation process. In other words, it can be said that we are not remembering what originally happened, but rather what we remembered the last time we thought about what happened. By disrupting the reconsolidation process that follows upon remembering, we can affect the content of memory.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Samad Ghorbanzadeh }

memory | September 21st, 2012 12:44 pm