‘The animal needing something knows how much it needs, the man does not.’ –Democritus

On 27 July 1890, aged 37, Van Gogh is believed to have shot himself in the chest with a revolver (although no gun was ever found). There were no witnesses and the location where he shot himself is unclear.

Biographer David Sweetman writes that the bullet was deflected by a rib bone and passed through his chest without doing apparent damage to internal organs—probably stopped by his spine. He was able to walk back to the Auberge Ravoux, where he was attended by two physicians. However, without a surgeon present the bullet could not be removed. After tending to him as best they could, the two physicians left him alone in his room, smoking his pipe.

The following morning (Monday), Theo rushed to be with his brother as soon as he was notified, and found him in surprisingly good shape, but within hours Vincent began to fail due to an untreated infection caused by the wound. Van Gogh died in the evening, 29 hours after he supposedly shot himself. According to Theo, his brother’s last words were: “The sadness will last forever.”

Van Gogh’s 2011 biographers Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith argue that van Gogh did not commit suicide but was shot accidentally by a boy he knew who had “a malfunctioning gun.”

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

In 1953, Nicolas de Staël’s depression led him to seek isolation in the south of France. He suffered from exhaustion, insomnia and depression. In the wake of a disappointing meeting with a disparaging art critic on March 16, 1955 he committed suicide. He leapt to his death from his eleventh story studio terrace, in Antibes. He was 41 years old.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

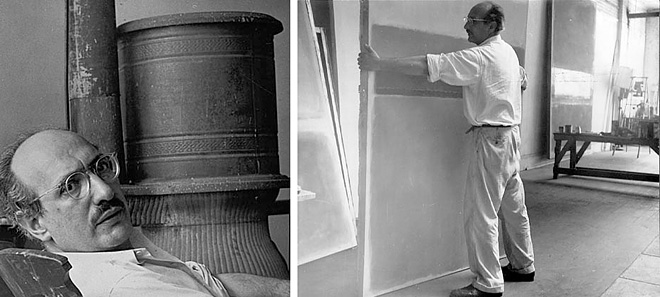

In the spring of 1968, Rothko was diagnosed with a mild aortic aneurysm. Ignoring doctor’s orders, Rothko continued to drink and smoke heavily, avoided exercise, and maintained an unhealthy diet.[…] Meanwhile, Rothko’s marriage had become increasingly troubled, and his poor health and impotence resulting from the aneurysm compounded his feeling of estrangement in the relationship. Rothko and his wife Mell separated on New Year’s Day 1969, and he moved into his studio.

On February 25, 1970, Oliver Steindecker, Rothko’s assistant, found the artist in his kitchen, lying dead on the floor in front of the sink, covered in blood. He had sliced his arms with a razor found lying at his side. The autopsy revealed that he had also overdosed on anti-depressants. He was sixty-six years old.

art { Nicolas de Stael, Still Life with Hammer, 1954 | Mark Rothko, Untitled (Black on Grey), 1970 }

related { the way we glamorise the suicides of famous artists inhibits our understanding of mental illness }