animals

Multiple viral diseases are spread through vectors, like ticks and mosquitoes, that result in massive health care issues and epidemics worldwide – my question has always been, if the vectors are infected with the virus, are they getting a disease? And, what is in it for the organism? Or, what is driving the vector to spread the viral infection?

George Dimopoulous’ group at Johns Hopkins University shed light on these questions in their latest publication on Dengue virus and the effect on its main vector, mosquito species Aedes aegypti.

{ Smaller Questions | Continue reading }

health, insects, science | April 5th, 2012 12:10 pm

{ The primate lab is home to 10 “shockingly smart” brown Capuchin monkeys trained to trade tokens for food. Researchers wondered whether monkeys, like humans, desire an expensive item more. | WSJ | full story }

animals, economics, science | April 3rd, 2012 7:25 am

animals, cuties | April 3rd, 2012 7:19 am

haha, horse, housing | March 28th, 2012 8:27 am

Pseudogenes are genes that used to have a function, but no longer do. If a gene contributes to an important function for the organism, offspring with deleterious mutations that ruin the gene will have lower fitness, and as a result won’t have as many offspring, if any at all. That mutated gene will likely not go to fixation (become prominent in the population). On the other hand, if the gene used to have a function, but no longer do, then mutations affecting the gene won’t be deleterious. (…)

Examples where pseudogenization is coupled to function is rare. A new study published in PNAS links genes that code for taste receptors to specific dietary changes in carnivorous mammals. Basically, animals that do not eat sweets don’t have receptors for sweetness (e.g., cats), and animals that swallows their food whole have no receptors for umami (e.g., sea lions, dolphins).

{ Pleiotropy | Continue reading }

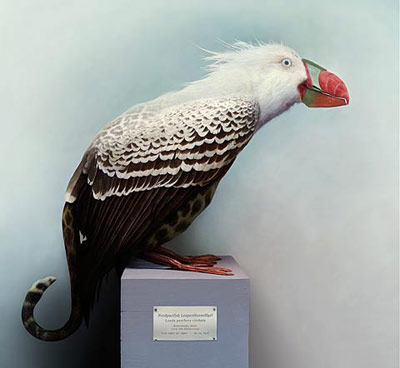

artwork { Darick Maasen }

animals, genes | March 27th, 2012 1:08 pm

dogs, photogs, visual design | March 27th, 2012 7:18 am

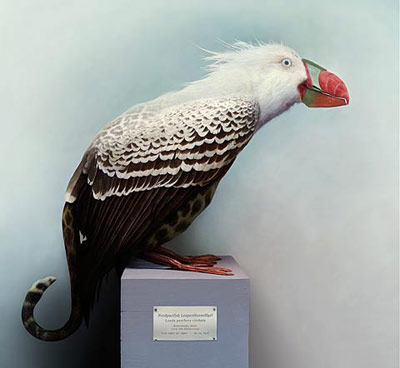

The extraordinary ability of birds and bats to fly at speed through cluttered environments such as forests has long fascinated humans. It raises an obvious question: how do these creatures do it?

Clearly they must recognise obstacles and exercise the necessary fine control over their movements to avoid collisions while still pursuing their goal. And they must do this at extraordinary speed.

From a conventional command and control point of view, this is a hard task. Object recognition and distance judgement are both hard problems and route planning even tougher.

Even with the vast computing resources that humans have access to, it’s not at all obvious how to tackle this problem. So how flying animals manage it with immobile eyes, fixed focus optics and much more limited data processing is something of a puzzle.

Today, Ken Sebesta and John Baillieul at Boston University reveal how they’ve cracked it. These guys say that flying animals use a relatively simple algorithm to steer through clutter and that this has allowed them to derive a fundamental law that determines the limits of agile flight.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

birds, science, technology | March 16th, 2012 3:22 pm

Putting Helium in a Dolphin. Two opposing hypotheses propose that tonal sounds arise either from tissue vibrations or through actual whistle production from vortices stabilized by resonating nasal air volumes. Here, we use a trained bottlenose dolphin whistling in air and in heliox [a mixture of helium and oxygen] to test these hypotheses.

(…)

Sixty-two percent of the dishwashers were positive for fungi.

(…)

Some years ago a colleague pointed out that there was a connection between paranoid symptomatology and the drawing in of joints on arms and legs on human figure drawings. [A researcher named] Buck states that emphasis upon knees suggests the presence of homosexual tendencies. Over a period of time, this investigator was impressed with the frequent connection between these two variables. This study was designed to determine the validity of this hypothesis.

(…)

In Study 1, 55 young women responded that they preferred men with hairy chests and circumcised penises.

{ Annals of Improbable Research | Special Body Parts Issue | PDF }

dolphins, haha, science | March 15th, 2012 12:52 pm

Why do birds sing in the morning?

There are two parts to the question, of course: why do birds sing? And why do they sing in the morning more than at other times of day? The first I think we’ve had a pretty good idea about for a long time, and there are two main reasons: to attract mates, and to claim their territory. (…)

One of the oldest ideas is that they sing in the morning because it’s still too dark to be out and about finding food, so you might as well sing. That’s a pretty solid idea - but it doesn’t really explain why they sing more in the morning than in the evening, when the light also fades - or even in the middle of the night. Another theory is that the conditions early in the morning - often cool and with lower humidity than later in the day - might be particularly good for letting the sounds of the song carry further, though recent experiments suggest that actually the middle of the day might be the best time to sing if acoustic conditions are what’s important so I don’t think that’s a winning idea. The third and most interesting theory is that birds sing most in the morning because that’s when, most days, they’ve got spare energy to use up. (…)

Here in Africa there’s an additional complication we should consider: many female birds sing too.

{ Safari Ecology | Continue reading }

birds | March 12th, 2012 2:51 pm

economics, horse, transportation | March 8th, 2012 3:01 pm

Whenever we are doing something, one of our brain hemispheres is more active than the other one. However, some tasks are only solvable with both sides working together.

PD Dr. Martina Manns and Juliane Römling of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum are investigating, how such specializations and co-operations arise. Based on a pigeon-model, they are proving for the first time in an experimental way, that the ability to combine complex impressions from both hemispheres, depends on environmental factors in the embryonic stage. (…)

First the pigeons have to learn to discriminate the combinations A/B and B/C with one eye, and C/D and D/E with the other one. Afterwards, they can use both eyes to decide between, for example, the colours B/D. However, only birds with embryonic light experience are able to solve this problem.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

Imagine the smell of an orange. Have you got it? Are you also picturing the orange, even though I didn’t ask you to? Try fish. Or mown grass. You’ll find it’s difficult to bring a scent to mind without also calling up an image. It’s no coincidence, scientists say: Your brain’s visual processing center is doing double duty in the smell department.

{ Inkfish | Continue reading }

birds, brain, eyes, olfaction | March 5th, 2012 1:20 pm

Jellyfish will not plague our oceans in the future as was previously thought, say researchers who have found no evidence for global increases in jellyfish blooms.

Despite media claims over the past few years that worldwide jellyfish numbers are increasing at an alarming rate, there has been no database of jellyfish numbers to back this up.

{ Cosmos | Continue reading }

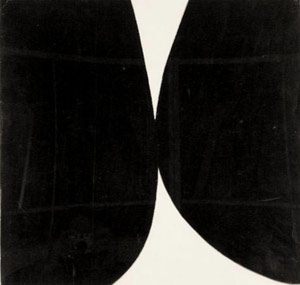

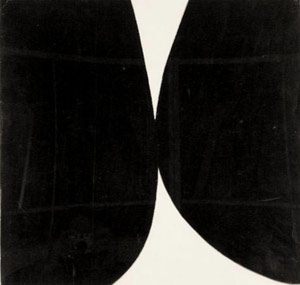

artwork { Ellsworth Kelly, Study for Rebound, 1955 }

Ellsworth Kelly, jellyfish | February 7th, 2012 12:34 pm

{ Cai Guo-Qiang, Head On, 2006 | 99 life-sized replicas of wolves and glass | The wolves were produced in Quanzhou, China, from January to June of 2006. They are fabricated from painted sheepskins and stuffed with hay and metal wires, with plastic lending contour to their faces and marbles for eyes. | Deutsche Guggenheim }

{ Guggenheim Museum, New York; Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao }

animals, archives, art | January 26th, 2012 1:48 pm

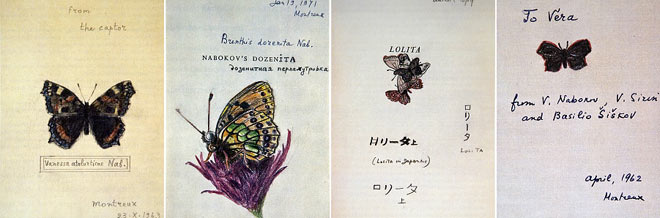

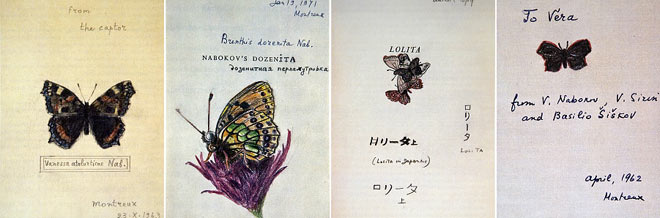

{ The drawings of butterflies done by Vladimir Nabokov were intended for “family use.” He made these on title pages of various editions of his works as a gift to his wife and son and sometimes to other relatives. None of these drawings portray real butterflies, both the images and the names he assigns to them are his invention. | Nabokov Museum | Continue reading }

animals, books | January 26th, 2012 1:00 pm

When things are bad, and I mean really bad, horribly you-are-in-the-jaws-of-death bad, sometimes you have to let go of something.

Like a tail.

The leopard gecko can, when hassled, have its tail fall off. Losing a limb (autotomy) is not a particularly unusual trick for this species. Lots of animals can drop legs and tails if necessary. But this one is noteworthy because if it does so, the tail doesn’t just come off, but it will continue to twist and writhe for up to several minutes after the tail has been separated from the rest of the body. (…)

Higham and Russell show that that the tail is doing at least two things. One is a slow, rhythmic swinging, and occasionally, much faster contortions that made the tail flip or jump around. The flips tend to fade out faster than the slower swinging, though.

{ NeuroDojo | Continue reading }

animals, science | January 23rd, 2012 12:10 pm

animals, marketing, visual design | January 23rd, 2012 12:02 pm

Peter Singer says if there is a range of ways of feeding ourselves, we should choose the way that causes the least unnecessary harm to animals. Most animal rights advocates say this means we should eat plants rather than animals. (…)

Published figures suggest that, in Australia, producing wheat and other grains results in:

• at least 25 times more sentient animals being killed per kilogram of useable protein

• more environmental damage, and

• a great deal more animal cruelty than does farming red meat.

{ Mike Archer | Continue reading }

related { American Meat Consumption Down 12.2% Since 2007. }

photo { Kelsey Bennett }

animals, economics, food, drinks, restaurants | January 20th, 2012 8:40 am

In the Cayman Islands, genetically modified mosquitoes are on the prowl. The insects are all male, and they’ve been engineered so that all their offspring die before reaching adulthood. By having sex with local females, they could father a new generation that perishes prematurely, before it gets the chance to spread diseases like dengue fever.

These GM insects, engineered by Luke Alphey at the University of Oxford, are part of a growing number of initiatives designed to fight disease by pitting mosquitoes against mosquitoes. Alphey’s tactic of breeding mosquitoes that beget unfit larvae is just one approach. Some groups are trying to make the insects more resistant to the disease-causing parasites they carry. Others have loaded them with life-shortening bacteria that outcompete those parasites. (…)

But all of these recent attempts to turn mosquitoes into malaria- and dengue-killing machines have something in common: The modified mosquitoes need to have lots of sex to spread their altered genes through the wild population. They must live long enough to become sexually active, and they have to compete successfully for mates with their wild peers. And that is a problem, because we still know surprisingly little about the behavior and ecology of mosquitoes, especially the males. How far do they travel? What separates the Casanovas from the sexual failures. What affects their odds of survival in the wild? How should you breed the growing mosquitoes to make them sexier?

{ Slate | Continue reading }

health, insects, science | January 19th, 2012 2:33 pm

Do all animal species have built-in expiration timers? Some fish and reptiles may not, but most creatures — and especially mammals — do seem to have an inner clock that triggers every individual’s decline to frailty after the middle years of fight-flight-and-reproduction run their course. (…) The same holds true across nearly all mammalian species. Few live to celebrate their billionth pulse. (…)

Most mammals our size and weight are already fading away by age twenty or so, when humans are just hitting their stride. By eighty, we’ve had about three billion heartbeats! That’s quite a bonus.

How did we get so lucky?

Biologists figure that our evolving ancestors needed drastically extended lifespans, because humans came to rely on learning rather than instinct to create sophisticated, tool-using societies. That meant children needed a long time to develop. A mere two decades weren’t long enough for a man or woman to amass the knowledge needed for complex culture, let alone pass that wisdom on to new generations. (In fact, chimps and other apes share some of this lifespan bonus, getting about half as many extra heartbeats.)

{ Sentient developments | Continue reading }

animals, science | January 17th, 2012 1:27 pm