Linguistics

The rape of the Sabine women, also known as the abduction of the Sabine women, was an incident in the legendary history of Rome in which the men of Rome committed bride kidnappings or mass abduction for the purpose of marriage, of women from other cities in the region. It has been a frequent subject of painters and sculptors, particularly since the Renaissance.

The word “rape” is the conventional translation of the Latin word raptio used in the ancient accounts of the incident. The Latin word means “taking”, “abduction” or “kidnapping”, but when used with women as its object, sexual assault is usually implied. […]

According to Roman historian Livy, the abduction of Sabine women occurred in the early history of Rome shortly after its founding in the mid-8th century BC and was perpetrated by Romulus [legendary founder and first king of Rome] and his predominantly male followers; it is said that after the foundation of the city, the population consisted solely of Latins and other Italic peoples, in particular male bandits. With Rome growing at such a steady rate in comparison to its neighbors, Romulus became concerned with maintaining the city’s strength. His main concern was that with few women inhabitants there would be no chance of sustaining the city’s population, without which Rome might not last longer than a generation. On the advice of the Senate, the Romans then set out into the surrounding regions in search of wives to establish families with. The Romans negotiated unsuccessfully with all the peoples that they appealed to, including the Sabines, who populated the neighboring areas. […]

The Romans devised a plan to abduct the Sabine women during the festival of Neptune Equester. They planned and announced a festival of games to attract people from all the nearby towns. At the festival, […] the Romans grabbed the Sabine women and fought off the Sabine men. […] All of the women abducted at the festival were said to have been virgins except for one married woman, Hersilia, who became Romulus’s wife and would later be the one to intervene and stop the ensuing war between the Romans and the Sabines.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Linguistics, crime, flashback | March 1st, 2025 3:47 am

English speakers have been deprived of a truly functional, second person plural pronoun since we let “ye” fade away a few hundred years ago.

“You” may address one person or a bunch, but it can be imprecise and unsatisfying. “You all”—as in “I’m talking to you all,” or “Hey, you all!”—sounds wordy and stilted. “You folks” or “you gang” both feel self-conscious. Several more economical micro-regional varieties (youz, yinz) exist, but they lack wide appeal.

But here’s what’s hard to explain: The first, a gender-neutral option, mainly thrives in the American South and hasn’t been able to steal much linguistic market share outside of its native habitat. The second, an undeniable reference to a group of men, is the default everywhere else, even when the “guys” in question are women, or when the speaker is communicating to a mixed gender group.

“You guys,” rolls off the tongues of avowed feminists every day, as if everyone has agreed to let one androcentric pronoun pass, while others (the generic “he” or “men” as stand-ins for all people) belong to the before-we-knew-better past. […]

One common defense of “you guys” that Mallinson encounters in the classroom and elsewhere is that it is gender neutral, simply because we use it that way. This argument also appeared in the New Yorker recently, in a column about a new book, The Life of Guy: Guy Fawkes, the Gunpowder Plot, and the Unlikely History of an Indispensable Word by writer and educator Allan Metcalf.

“Guy” grew out of the British practice of burning effigies of the Catholic rebel Guy Fawkes, Metcalf explains in the book. The flaming likenesses, first paraded in the early 1600s, came to be called “guys,” which evolved to mean a group of male lowlifes, he wrote in a recent story for Time. Then, by the 18th century, “guys” simply meant “men” without any pejorative connotations. By the 1930s, according to the Washington Post, Americans had made the leap to calling all persons “guys.”

{ Quartz | Continue reading }

Linguistics | November 29th, 2019 10:13 pm

[S]ome languages—such as Japanese, Basque, and Italian—are spoken more quickly than others. […]

Linguists have spent more time studying not just speech rate, but the effort a speaker has to exert to get a message across to a listener. By calculating how much information every syllable in a language conveys, it’s possible to compare the “efficiency” of different languages. And a study published today in Science Advances found that more efficient languages tend to be spoken more slowly. In other words, no matter how quickly speakers chatter, the rate of information they’re transmitting is roughly the same across languages.

The basic problem of “efficiency,” in linguistics, starts with the trade-off between effort and communication. It takes a certain amount of coordination, and burns a certain number of calories, to make noises come out of your mouth in an intelligible way. And those noises can be more or less informative to a listener, based on how predictable they are. If you and I are discussing dinosaurs, you wouldn’t be surprised to hear me rattle off the names of my favorite species. But if a stranger walks up to you on the street and announces, “Diplodocus!” it’s unexpected. It narrows the scope of possible conversation topics greatly and is therefore highly informative.

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

image { Six soap bubbles inside one another, from The Windsor Magazine, 1902 }

Linguistics | September 8th, 2019 8:51 am

Based on the analysis of 190 studies (17,887 participants), we estimate that the average silent reading rate for adults in English is 238 word per minute (wpm) for non-fiction and 260 wpm for fiction. The difference can be predicted by the length of the words, with longer words in non-fiction than in fiction. The estimates are lower than the numbers often cited in scientific and popular writings. […] The average oral reading rate (based on 77 studies and 5,965 participants) is 183 wpm.

{ PsyArXiv | Continue reading }

Linguistics | April 13th, 2019 10:26 am

GPT-2 is trained with a simple objective: predict the next word, given all of the previous words within some text. […] GPT-2 displays a broad set of capabilities, including the ability to generate conditional synthetic text samples of unprecedented quality, where we prime the model with an input and have it generate a lengthy continuation. […]

SYSTEM PROMPT (HUMAN-WRITTEN)

In a shocking finding, scientist discovered a herd of unicorns living in a remote, previously unexplored valley, in the Andes Mountains. Even more surprising to the researchers was the fact that the unicorns spoke perfect English.

MODEL COMPLETION (MACHINE-WRITTEN, 10 TRIES)

The scientist named the population, after their distinctive horn, Ovid’s Unicorn. These four-horned, silver-white unicorns were previously unknown to science. Now, after almost two centuries, the mystery of what sparked this odd phenomenon is finally solved. […] While examining these bizarre creatures the scientists discovered that the creatures also spoke some fairly regular English. Pérez stated, “We can see, for example, that they have a common ‘language,’ something like a dialect or dialectic.” Dr. Pérez believes that the unicorns may have originated in Argentina, where the animals were believed to be descendants of a lost race of people who lived there before the arrival of humans in those parts of South America.While their origins are still unclear, some believe that perhaps the creatures were created when a human and a unicorn met each other in a time before human civilization. According to Pérez, “In South America, such incidents seem to be quite common.”

{ Open AI | Continue reading }

related { The technology behind OpenAI’s fiction-writing, fake-news-spewing AI, explained }

more { Japanese scientists used A.I. to read minds + NONE of these people exist | Thanks Tim }

quote { Who is Descartes’ Evil Genius? }

Linguistics, robots & ai | February 16th, 2019 10:28 am

One of the curious features of language is that it varies from one place to another.

Even among speakers of the same language, regional variations are common, and the divide between these regions can be surprisingly sharp. […]

For example, the term “you guys” is used most often in the northern parts of the US, while “y’all” is used more in the south.

{ Technology Review | Continue reading }

Linguistics, U.S. | November 29th, 2018 7:39 am

The familiarity of the phrase ‘much ado about nothing’ belies its complexity. In Shakespeare’s day ‘nothing’ was pronounced the same as ‘noting’, and the play contains numerous punning references to ‘noting’, both in the sense of observation and in the sense of ‘notes’ or messages. […]

‘Nothing’ was Elizabethan slang for the vagina (a vacancy, ‘no-thing’ or ‘O thing’). Virginity — a state of potentiality rather than actuality — is also much discussed in the play, and it is these twin absences — the vagina and virginity — that lead, in plot terms, to the ‘much ado’ of the title.

{ The Guardian | Continue reading }

photo { Olivia Rocher, I Fought the Law (Idaho), 2016 }

Linguistics, allegories, poetry, sex-oriented | August 1st, 2018 3:26 pm

Linguistics | May 17th, 2018 2:00 pm

With a few minor exceptions, there are really only two ways to say “tea” in the world. One is like the English term—té in Spanish and tee in Afrikaans are two examples. The other is some variation of cha, like chay in Hindi.

Both versions come from China. How they spread around the world offers a clear picture of how globalization worked before “globalization” was a term anybody used. The words that sound like “cha” spread across land, along the Silk Road. The “tea”-like phrasings spread over water, by Dutch traders bringing the novel leaves back to Europe.

{ Quartz | Continue reading }

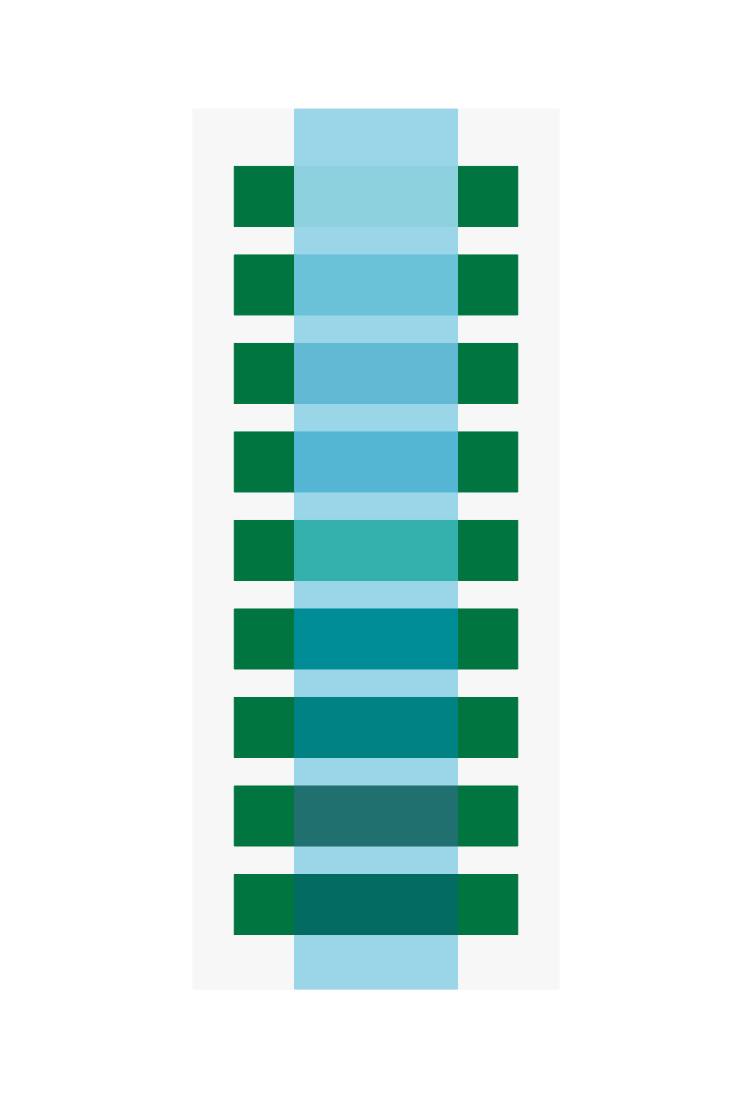

art { Josef Albers, Interaction of Color, 1963 }

Linguistics, food, drinks, restaurants | February 16th, 2018 12:34 pm

Here, we analysed 200 million online conversations to investigate transmission between individuals. We find that the frequency of word usage is inherited over conversations, rather than only the binary presence or absence of a word in a person’s lexicon. We propose a mechanism for transmission whereby for each word someone encounters there is a chance they will use it more often. Using this mechanism, we measure that, for one word in around every hundred a person encounters, they will use that word more frequently. As more commonly used words are encountered more often, this means that it is the frequencies of words which are copied.

{ Journal of the Royal Society Interface | Continue reading }

Linguistics | February 15th, 2018 1:11 pm

Grapheme-color synesthesia is a neurological phenomenon in which viewing a grapheme elicits an additional, automatic, and consistent sensation of color.

Color-to-letter associations in synesthesia are interesting in their own right, but also offer an opportunity to examine relationships between visual, acoustic, and semantic aspects of language. […]

Numerous studies have reported that for English-speaking synesthetes, “A” tends to be colored red more often than predicted by chance, and several explanatory factors have been proposed that could explain this association.

Using a five-language dataset (native English, Dutch, Spanish, Japanese, and Korean speakers), we compare the predictions made by each explanatory factor, and show that only an ordinal explanation makes consistent predictions across all five languages, suggesting that the English “A” is red because the first grapheme of a synesthete’s alphabet or syllabary tends to be associated with red.

We propose that the relationship between the first grapheme and the color red is an association between an unusually-distinct ordinal position (”first”) and an unusually-distinct color (red).

{ Cortex | Continue reading }

A Black, E white, I red, U green, O blue: vowels,

Someday I shall tell of your mysterious births

{ Arthur Rimbaud | Continue reading }

art { Roland Cat, The pupils of their eyes, 1985 }

Linguistics, colors, neurosciences | February 12th, 2018 1:27 pm

Cioffi endorses the Oxford comma, the one before and in a series of three or more. On the question of whether none is singular or plural, he is flexible: none can mean not a single one and take a singular verb, or it can mean not any and take a plural verb. His sample “None are boring” (from the New Yorker, where I work) was snipped from a review of a show of photographs by Richard Avedon. Cioffi would prefer the singular in this instance — “None is boring” — arguing that it “emphasizes how not a single, solitary one of these Avedon photographs is boring”. To me, putting so much emphasis on the photos’ not being boring suggests that the critic was hoping for something boring. I would let it stand. […]

“that usually precedes elements that are essential to your sentence’s meaning [restrictive], while which typically introduces ‘nonessential’ elements [non-restrictive], and usually refers to the material directly before it.” Americans sometimes substitute which for that, thinking it makes us sound more proper (i.e. British). On both sides of the Atlantic, the classic nonrestrictive which is preceded by a comma.

{ The Times Literary Supplement | Continue reading }

Linguistics | June 13th, 2016 11:30 am

After 2.5 millennia of philosophical deliberation and psychological experimentation, most scholars have concluded that humor arises from incongruity. We highlight 2 limitations of incongruity theories of humor.

First, incongruity is not consistently defined. The literature describes incongruity in at least 4 ways: surprise, juxtaposition, atypicality, and a violation.

Second, regardless of definition, incongruity alone does not adequately differentiate humorous from nonhumorous experiences.

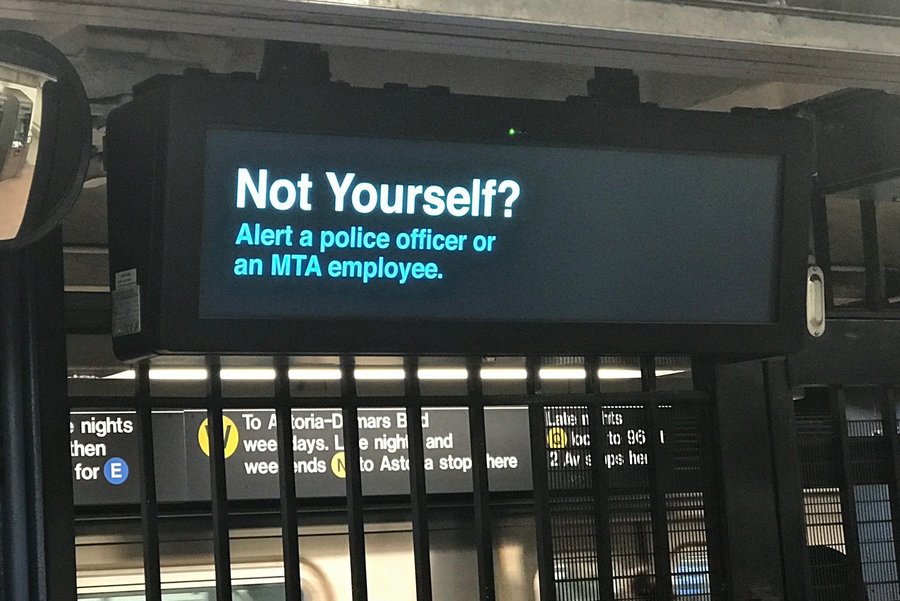

We suggest revising incongruity theory by proposing that humor arises from a benign violation: something that threatens a person’s well-being, identity, or normative belief structure but that simultaneously seems okay.

Six studies, which use entertainment, consumer products, and social interaction as stimuli, reveal that the benign violation hypothesis better differentiates humorous from nonhumorous experiences than common conceptualizations of incongruity. A benign violation conceptualization of humor improves accuracy by reducing the likelihood that joyous, amazing, and tragic situations are inaccurately predicted to be humorous.

{ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology }

photo { William Klein }

Linguistics, psychology | January 21st, 2016 1:55 pm

…the differences between “U” (Upper-class) and “non-U” (Middle Class) usages […]

The genteel offer ale rather than beer; invite one to step (not come) this way; and assist (never help) one another to potatoes. […]

When Prince William and Kate Middleton split up in 2007 the press blamed it on Kate’s mother’s linguistic gaffes at Buckingham Palace, where she reputedly responded to the Queen’s How do you do? with the decidedly non-U Pleased to meet you (the correct response being How do you do?), and proceeded to ask to use the toilet (instead of the U lavatory).

{ The Conversation | Continue reading }

Linguistics | January 12th, 2016 1:14 pm

Two pennies can be considered the same — both are pennies, just as two elephants can be considered the same, as both are elephants. Despite the vast difference between pennies and elephants, we easily notice the common relation of sameness that holds for both pairs. Analogical ability — the ability to see common relations between objects, events or ideas — is a key skill that underlies human intelligence and differentiates humans from other apes.

While there is considerable evidence that preschoolers can learn abstract relations, it remains an open question whether infants can as well. In a new Northwestern University study, researchers found that infants are capable of learning the abstract relations of same and different after only a few examples.

“This suggests that a skill key to human intelligence is present very early in human development, and that language skills are not necessary for learning abstract relations,” said lead author Alissa Ferry, who conducted the research at Northwestern.

{ Lunatic Laboratories | Continue reading }

Linguistics, psychology | May 26th, 2015 11:57 am

This paper argues that there are at least five reasons why the claim that the Bible is to be taken literally defies logic or otherwise makes no sense, and why literalists are in no position to claim that they have the only correct view of biblical teachings.

First, many words are imprecise and therefore require interpretation, especially to fill in gaps between general words and their application to specific situations. Second, if you are reading an English version of the Bible you are already dealing with the interpretations of the translator since the earliest Bibles were written in other languages. Third, biblical rules have exceptions, and those exceptions are often not explicitly set forth. Fourth, many of the Bible’s stories defy logic and our experiences of the world. Fifth, there are sometimes two contrary versions of the same event, so if we take one literally then we cannot take the second one literally. In each of these five cases, there is no literal reading to be found.

Furthermore, this paper sets forth three additional reasons why such a literalist claim probably should not be made even if it did not defy logic to make such a claim. These include The Scientific Argument: the Bible contradicts modern science; The Historical Argument: the Bible is historically inaccurate; and The Moral Argument: the Bible violates contemporary moral standards.

{ Open Journal of Philosophy | PDF }

photo { Roger Mimick }

Linguistics, flashback | April 22nd, 2015 11:00 am

Many people spontaneously use the word (or sound) “Um” in conversation, a phenomenon which has prompted a considerable volume of academic attention. A question arises though, can someone be induced to say “Um” by chemical means – say with the use of a powerful anaesthetic? Like, for example Ketamine? […]

[V]olunteers who were given “low doses” and “high doses” of Ketamine tended to use the words “um” and “uh” significantly more than those who received a placebo only.

{ Improbable | Continue reading }

Linguistics, drugs | March 12th, 2015 3:07 pm

Most people who describe themselves as demisexual say they only rarely feel desire, and only in the context of a close relationship. Gray-asexuals (or gray-aces) roam the gray area between absolute asexuality and a more typical level of interest. […]

“Every single asexual I’ve met embraces fluidity—I might be gray or asexual or demisexual,” says Claudia, a 24-year-old student from Las Vegas. “Us aces are like: whatevs.”

{ Wired | Continue reading }

photo { Nate Walton }

Linguistics, experience, sex-oriented | March 10th, 2015 1:05 pm

Facebook will soon be able to ID you in any photo

The intention is not to invade the privacy of Facebook’s more than 1.3 billion active users, insists Yann LeCun, a computer scientist at New York University in New York City who directs Facebook’s artificial intelligence research, but rather to protect it. Once DeepFace identifies your face in one of the 400 million new photos that users upload every day, “you will get an alert from Facebook telling you that you appear in the picture,” he explains. “You can then choose to blur out your face from the picture to protect your privacy.” Many people, however, are troubled by the prospect of being identified at all—especially in strangers’ photographs. Facebook is already using the system, although its face-tagging system only reveals to you the identities of your “friends.”

{ Science | Continue reading }

related { Bust detection algorithm }

photo { Rachel Roze }

Linguistics, faces, social networks | February 7th, 2015 3:03 pm

The weather impacts not only upon our mood but also our voice. An international research team has analysed the influence of humidity on the evolution of languages.

Their study has revealed that languages with a wide range of tone pitches are more prevalent in regions with high humidity levels. In contrast, languages with simpler tone pitches are mainly found in drier regions. This is explained by the fact that the vocal folds require a humid environment to produce the right tone.

The tone pitch is a key element of communication in all languages, but more so in some than others. German or English, for example, still remain comprehensible even if all words are intonated evenly by a robot. In Mandarin Chinese, however, the pitch tone can completely change the meaning of a word.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

Linguistics, noise and signals, water | January 25th, 2015 5:53 am