Linguistics

The weather impacts not only upon our mood but also our voice. An international research team has analysed the influence of humidity on the evolution of languages.

Their study has revealed that languages with a wide range of tone pitches are more prevalent in regions with high humidity levels. In contrast, languages with simpler tone pitches are mainly found in drier regions. This is explained by the fact that the vocal folds require a humid environment to produce the right tone.

The tone pitch is a key element of communication in all languages, but more so in some than others. German or English, for example, still remain comprehensible even if all words are intonated evenly by a robot. In Mandarin Chinese, however, the pitch tone can completely change the meaning of a word.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

Linguistics, noise and signals, water | January 25th, 2015 5:53 am

DNA is generally regarded as the basic building block of life itself. In the most fundamental sense, DNA is nothing more than a chemical compound, albeit a very complex and peculiar one. DNA is an information-carrying molecule. The specific sequence of base pairs contained in a DNA molecule carries with it genetic information, and encodes for the creation of particular proteins. When taken as a whole, the DNA contained in a single human cell is a complete blueprint and instruction manual for the creation of that human being.

In this article we discuss myriad current and developing ways in which people are utilizing DNA to store or convey information of all kinds. For example, researchers have encoded the contents of a whole book in DNA, demonstrating the potential of DNA as a way of storing and transmitting information. In a different vein, some artists have begun to create living organisms with altered DNA as works of art. Hence, DNA is a medium for the communication of ideas. Because of the ability of DNA to store and convey information, its regulation must necessarily raise concerns associated with the First Amendment’s prohibition against the abridgment of freedom of speech.

New and developing technologies, and the contemporary and future social practices they will engender, necessitate the renewal of an approach towards First Amendment coverage that takes into account the purposes and values incarnated in the Free Speech Clause of the Constitution.

{ Charleston School of Law | Continue reading }

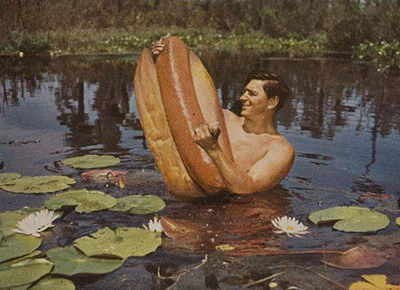

photo { Bruce Davidson }

Linguistics, genes, law | January 2nd, 2015 6:55 am

This paper considers when a firm’s freely chosen name can signal meaningful information about its quality, and examines a setting in which it does.

Plumbing firms with names beginning with an “A” or a number receive five times more service complaints, on average. In addition, firms use names beginning with an “A” or a number more often in larger markets, and those that do have higher prices.

These results reflect consumers’ search decisions and extend to online position auctions: plumbing firms that advertise on Google receive more complaints, which contradicts prior theoretical predictions but fits the setting considered here.

{ Ryan C. McDevitt | PDF }

Linguistics, marketing | September 10th, 2014 3:12 pm

The term “stress” had none of its contemporary connotations before the 1920s. It is a form of the Middle English destresse, derived via Old French from the Latin stringere, “to draw tight.” The word had long been in use in physics to refer to the internal distribution of a force exerted on a material body, resulting in strain. In the 1920s and 1930s, biological and psychological circles occasionally used the term to refer to a mental strain or to a harmful environmental agent that could cause illness.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

The modern idea of stress began on a rooftop in Canada, with a handful of rats freezing in the winter wind.

This was 1936 and by that point the owner of the rats, an endocrinologist named Hans Selye, had become expert at making rats suffer for science.

“Almost universally these rats showed a particular set of signs,” Jackson says. “There would be changes particularly in the adrenal gland. So Selye began to suggest that subjecting an animal to prolonged stress led to tissue changes and physiological changes with the release of certain hormones, that would then cause disease and ultimately the death of the animal.”

And so the idea of stress — and its potential costs to the body — was born.

But here’s the thing: The idea of stress wasn’t born to just any parent. It was born to Selye, a scientist absolutely determined to make the concept of stress an international sensation.

{ NPR | Continue reading }

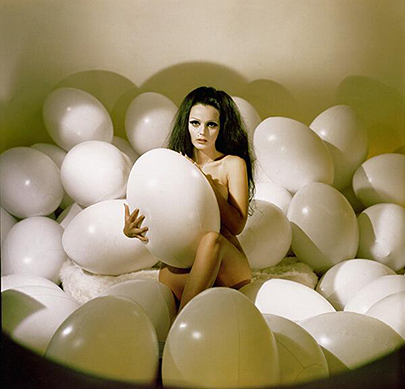

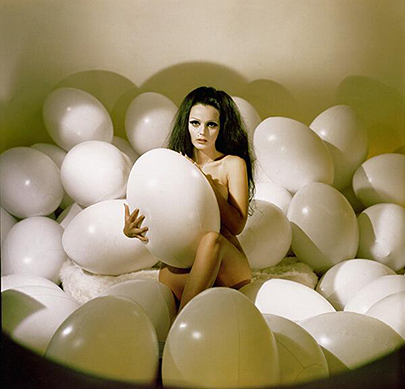

art { Richard Phillips, Blauvelt, 2013 }

Linguistics, flashback, health | July 10th, 2014 9:58 am

“Would you please take a selfie of my friend and I in front of this window?”

She was not aware that she had approached a linguist. […]

It would not be like him to snarl that of my friend and I should be of my friend and me (or perhaps better, of me and my friend). Nor did he remonstrate with the woman over her rather extraordinary misuse of the noun selfie.

{ Language Log | Continue reading }

unrelated { Photographer countersues Empire State Building for $5M over topless photos }

Linguistics, photogs | March 20th, 2014 3:15 pm

More than 400 years after Shakespeare wrote it, we can now say that “Romeo and Juliet” has the wrong name. Perhaps the play should be called “Juliet and Her Nurse,” which isn’t nearly as sexy, or “Romeo and Benvolio,” which has a whole different connotation.

I discovered this by writing a computer program to count how many lines each pair of characters in “Romeo and Juliet” spoke to each other, with the expectation that the lovers in the greatest love story of all time would speak more than any other pair.

{ FiveThirtyEight | Continue reading }

Linguistics, books | March 19th, 2014 7:40 am

Ultracrepidarian (n):”Somebody who gives opinions on subjects they know nothing about.”

Groke (v): “To gaze at somebody while they’re eating in the hope that they’ll give you some of their food.” My dog constantly grokes at me longingly while I eat dinner.

{ BI | Continue reading }

Linguistics, buffoons | March 3rd, 2014 6:35 am

Author profiling is a problem of growing importance in applications in forensics, security, and marketing. E.g., from a forensic linguistics perspective one would like being able to know the linguistic profile of the author of a harassing text message (language used by a certain type of people) and identify certain characteristics. Similarly, from a marketing viewpoint, companies may be interested in knowing, on the basis of the analysis of blogs and online product reviews, the demographics of people that like or dislike their products. The focus is on author profiling in social media since we are mainly interested in everyday language and how it reflects basic social and personality processes.

{ PAN | Continue reading }

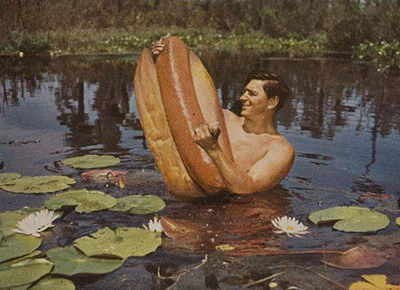

photos { Neal Barr, Texas Track Club, 1964 }

Linguistics, social networks, technology | February 21st, 2014 7:02 am

…the specific forms of linguistic mayhem performed by “young people nowadays.” For American teenagers, these examples usually include the discourse marker like, rising final intonation on declaratives, and the address term dude, which is cited as an example of the inarticulateness of young men in particular. This stereotype views the use of dude as unconstrained – a sign of inexpressiveness in which one word is used for any and all utterances. […]

The data presented here confirm that dude is an address term that is used mostly by young men to address other young men; however, its use has expanded so that it is now used as a general address term for a group (same or mixed gender), and by and to women. Dude is developing into a discourse marker that need not identify an addressee, but more generally encodes the speaker’s stance to his or her current addressee(s). The term is used mainly in situations in which a speaker takes a stance of solidarity or camaraderie, but crucially in a nonchalant, not-too-enthusiastic manner.

{ American Speech | Continue reading | via TNI }

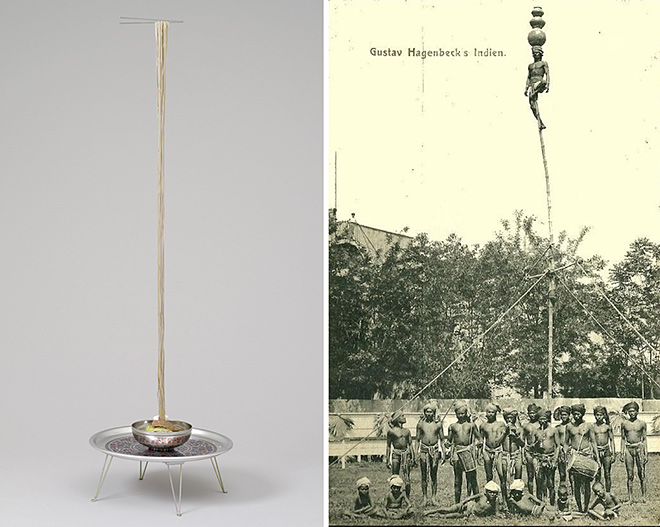

images { Oh Seung Yul, naeng myun, 2011 | Postcard, Deutsches Reich. 1900 }

Linguistics | February 2nd, 2014 1:29 pm

“I want you to know…” or “I’m just saying…” or “I hate to be the one to tell you this…” Often, these phrases imply the opposite of what the words mean, as with the phrase, “I’m not saying…” as in “I’m not saying we have to stop seeing each other, but…” […]

Language experts have textbook names for these phrases—”performatives,” or “qualifiers.” Essentially, taken alone, they express a simple thought, such as “I am writing to say…” At first, they seem harmless, formal, maybe even polite. But coming before another statement, they often signal that bad news, or even some dishonesty on the part of the speaker, will follow. […]

Their use may be increasing as a result of social media, where people use phrases such as “I am thinking that…” or “As far as I know…” both to avoid committing to a definitive position and to manage the impression they make in print.

{ WSJ | Continue reading }

photo { Marek Chorzepa }

Linguistics | January 21st, 2014 4:30 pm

Spoken irony, for the most part, avoids such pitfalls by virtue of tone of voice and the body language with which we accompany it. By cocking an eyebrow, by feigning enthusiasm or boredom, we give an attentive listener the clues they need to extract our true meaning. The problems most often arise not when we utter an ironic statement but when we try to write it down.

Yet written language is not without its own body language of sorts in the form of punctuation, and to approximate a specific tone of voice we might employ italic or bold text. Despite this, writers persist in looking for alternative ways to signal irony. For evidence of this we need look no further than the prevalence of the “smileys” with which we decorate jokes sent over SMS, instant messaging and email. Plainly, we do not trust conventional marks alone to convey our meaning. Even a crude :-) or ;-) is preferable to having an ironic comment misunderstood by its reader.

{ New Statesman | Continue reading }

Linguistics | October 25th, 2013 10:27 am

Cursing, researchers say, is a human universal. Every language, dialect or patois ever studied, whether living or dead, spoken by millions or by a single small tribe, turns out to have its share of forbidden speech, some variant on comedian George Carlin’s famous list of the seven dirty words that are not supposed to be uttered on radio or television. […]

Researchers point out that cursing is often an amalgam of raw, spontaneous feeling and targeted, gimlet-eyed cunning. When one person curses at another, they say, the curser rarely spews obscenities and insults at random, but rather will assess the object of his wrath, and adjust the content of the “uncontrollable” outburst accordingly.

Because cursing calls on the thinking and feeling pathways of the brain in roughly equal measure and with handily assessable fervor, scientists say that by studying the neural circuitry behind it, they are gaining new insights into how the different domains of the brain communicate — and all for the sake of a well-venomed retort. […]

“Studies show that if you’re with a group of close friends, the more relaxed you are, the more you swear,” Burridge said.

{ SF Gate/Natalie Angier | Continue reading }

Linguistics, neurosciences | October 11th, 2013 3:07 pm

On October 9th South Koreans celebrate the 567th birthday of Hangul, the country’s native writing system, with a day off work. South Korea is one of the few countries in the world to celebrate its writing system. […]

The day commemorates the introduction of the new script in the mid-15th century, making Hangul one of the youngest alphabets in the world. It is unusual for at least two more reasons: rather than evolving from pictographs or imitating other writing systems, the Korean script was invented from scratch for the Korean language. And, though it is a phonemic alphabet, it is written in groups of syllables rather than linearly. How was Hangul created?

{ The Economist | Continue reading }

photo { Ray Metzker }

Linguistics, asia, flashback | October 10th, 2013 11:11 am

When I eventually returned to my desk at Keele University School of Psychology I wondered why it was that people swear in response to pain. Was it a coping mechanism, an outlet for frustration, or what? […]

Professor Timothy Jay of Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in the States […] has forged a career investigating why people swear and has written several books on the topic. His main thesis is that swearing is not, as is often argued, a sign of low intelligence and inarticulateness, but rather that swearing is emotional language.

{ The Pyschologist | Continue reading }

Linguistics, psychology | September 10th, 2013 2:11 pm

An open source project to combat “stylometry”, the study of attributing authorship to documents based only on the linguistic style they exhibit, is proving that it is possible to change writing style so as to evade detection.

Artificial Intelligence techniques are routinely used to detect plagiarism and recently were employed to reveal that Harry Potter author J K Rowling is indeed the author of The Cuckoo’s Calling published under the byline of Robert Galbraith.

Now software is tackling the opposite problem–anonymizing writing style to protect the identity of the originator.

{ I Programmer | Continue reading }

Linguistics, technology | August 5th, 2013 10:26 am

Linguistics, photogs | June 12th, 2013 4:43 am

When Latin lost many of its inflectional exponents and morphed into what is now modern French, the pronouns of Latin, which were used for emphasis only, became obligatory.

{ Frontiers | Continue reading }

The Romance languages are all the related languages derived from Vulgar Latin.

In 2007, the five most widely spoken Romance languages by number of native speakers were Spanish (385 million), Portuguese (210 million), French (75 million), Italian (60 million), and Romanian (23 million).

The Romance languages developed from Latin in the sixth to ninth centuries.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Linguistics | May 12th, 2013 2:06 pm

I do not know where family doctors acquired illegibly perplexing handwriting; nevertheless, extraordinary pharmaceutical intellectuality, counterbalancing indecipherability, transcendentalizes intercommunications’ incomprehensibleness.

(Dmitri Borgmann, Language on Vacation: An Olio of Orthographical Oddities. Scribner, 1965)

This is a ‘rhopalic’ sentence: A sentence or a line of poetry in which each word contains one letter or one syllable more than the previous word.

{ Quora | Continue reading }

related { “Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo” is a grammatically valid sentence in American English | Wikipedia }

photo { Paul McDonough }

Linguistics | April 5th, 2013 12:11 pm

Why does the alphabet’s 24th letter designate the nameless?

[…]

It probably starts with the 17th-century French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes, who in his 1637 book “La Géometrie” first systematically used a lower-case “x,” together with “y” and “z,” to signify an unknown quantity in simple algebraic equations. […] We now jump […] from 1637 to 1895, when Wilhelm Röntgen discovered a new type of radiation. Röntgen, who wasn’t sure just what he had come across, named his find in German X-Strahlen, using the algebraic symbol for something unknown. […] “X-ray” has remained our English word and has also contributed, with the help of the term “X-ray vision,” to x’s ability to evoke the uncanny.

{ Forward | Continue reading }

previously { XXX, XXY, XYY }

photo { Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin }

Linguistics, flashback | March 22nd, 2013 10:11 am

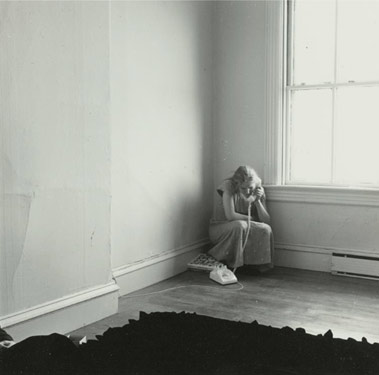

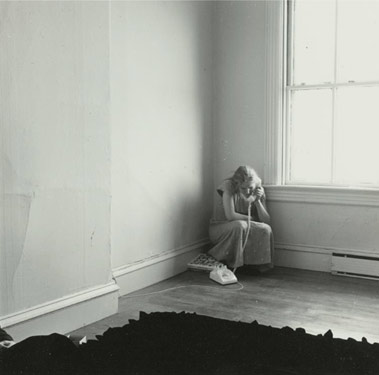

One in four of us will struggle with a mental illness this year, the most common being depression and anxiety. The upcoming publication of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM) will expand the list of psychiatric classifications, further increasing the number of people who meet criteria for disorder. But will this increase in diagnoses really mean more people are getting the help they need? And to what extent are we pathologising normal human behaviours, reactions and mood swings?

The revamping of the DSM – an essential tool for mental health practitioners and researchers alike, often referred to as the ‘psychiatry bible’ – is long overdue; the previous version was published in 1994. This revision provides an excellent opportunity to scrutinise what qualifies as psychiatric illness and the criteria used to make these diagnoses. But will the experts make the right calls?

The complete list of new diagnoses was released recently and included controversial disorders such as ‘excessive bereavement after a loss’ and ‘internet use gaming disorder’. The inclusion of these syndromes raises the important question of what actually qualifies as pathology.

{ King’s Review | Continue reading }

photo { Francesca Woodman, Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island (Self-portrait on the telephone), 1975-1976 }

Linguistics, controversy, psychology | February 22nd, 2013 1:56 pm