Linguistics

Regarding exorcism, the Catholic Encyclopedia says:

Exorcism is (1) the act of driving out, or warding off, demons, or evil spirits, from persons, places, or things, which are believed to be possessed or infested by them, or are liable to become victims or instruments of their malice; (2) the means employed for this purpose, especially the solemn and authoritative adjuration of the demon, in the name of God, or any of the higher power in which he is subject.

[…]

In contrast, the rationalist perspective presents historical and medically-based views of possession phenomena in terms of epilepsy, schizophrenia, and possession trance disorder (PTD), a possible variant of dissociative identity disorder. Nothing evil or supernatural takes over the identity of the person with PTD. Nonetheless, exorcisms performed on mentally ill people continue to this day. […]

In DSM-IV, spirit possession falls under the category of Dissociative Disorder Not Otherwise Specified, with more specific research criteria (but not an official diagnosis) fitting Dissociative Trance Disorder (possession trance):

Dissociative trance disorder: single or episodic disturbances in the state of consciousness, identity, or memory that are indigenous to particular locations and cultures. Dissociative trance involves narrowing of awareness of immediate surroundings or stereotyped behaviors or movements that are experienced as being beyond one’s control. Possession trance involves replacement of the customary sense of personal identity by a new identity, attributed to the influence of a spirit, power, deity, or other person and associated with stereotyped involuntary movements or amnesia, and is perhaps the most common dissociative disorder in Asia. Examples include amok (Indonesia), bebainan (Indonesia), latah (Malaysia), pibloktoq (Arctic), ataque de nervios (Latin America), and possession (India). The dissociative or trance disorder is not a normal part of a broadly accepted collective cultural or religious practice.

[…]

Will there be changes for Dissociative Trance Disorder (DTD) in DSM-5?

{ Neurocritic | Continue reading }

Linguistics, psychology | January 28th, 2013 2:33 pm

{ A cephalophore is a saint who is generally depicted carrying his or her own head. }

Linguistics, weirdos | January 28th, 2013 11:13 am

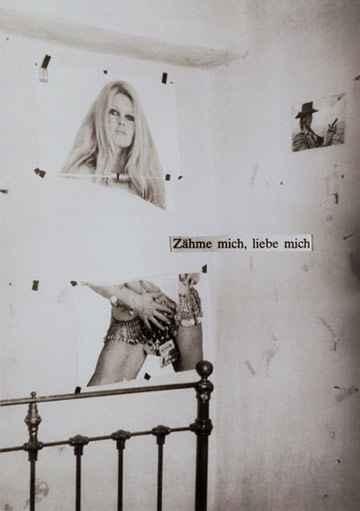

Far more insidious is the insistence by some feminists on mocking transsexual women and denying their existence.

The word that annoys these so-called feminists most is ‘cis’, or ‘cissexual’. This is a term coined in recent years to refer to people who are not transsexual. The response is instant and vicious: “we’re not cissexual, we’re normal - we don’t want to be associated with you freaks!” Funnily enough, that’s just the kind of pissing and whining that a lot of straight people came out with when the term ‘heterosexual’ first began to be used as an antonym of ‘homosexual.’ Don’t call us ‘heterosexuals’, they said - we’re normal, and you don’t belong.

{ Laurie Penny | Continue reading | via Nathan/Zungu Zungu }

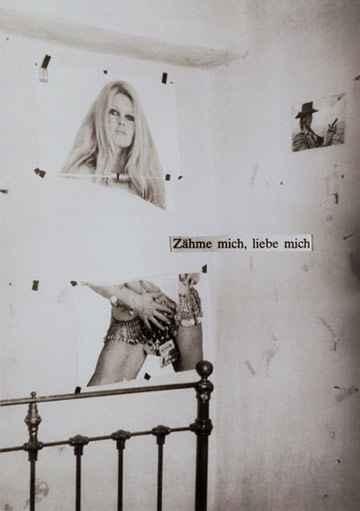

art { Astrid Klein }

Linguistics, genders | January 20th, 2013 3:10 pm

Age-otori (Japanese): To look worse after a haircut

Tingo (Pascuense language of Easter Island): To borrow objects one by one from a neighbor’s house until there is nothing left

Backpfeifengesicht (German): A face badly in need of a fist

{ via The Atlantic | Continue reading }

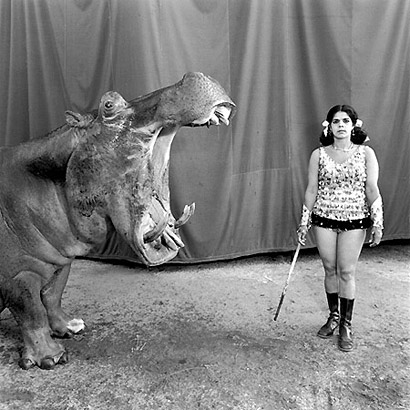

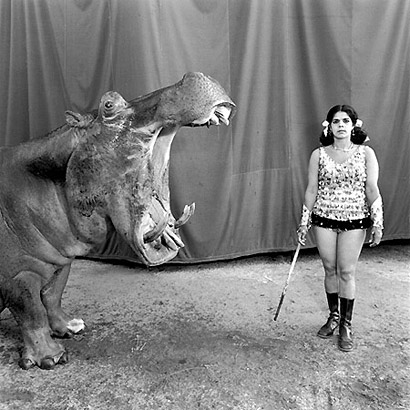

photo { Mary Ellen Mark }

Linguistics, within the world | January 9th, 2013 3:19 pm

Linguistics | October 17th, 2012 8:33 am

Canadian researchers have come up with a new, precise definition of boredom based on the mental processes that underlie the condition.

Although many people may see boredom as trivial and temporary, it actually is linked to a range of psychological, social and health problems, says Guelph psychology professor Mark Fenske. […]

After reviewing existing psychological science and neuroscience studies, they defined boredom as “an aversive state of wanting, but being unable, to engage in satisfying activity,” which arises from failures in one of the brain’s attention networks.

In other words, you become bored when:

• you have difficulty paying attention to the internal information, such as thoughts or feelings, or outside stimuli required to take part in satisfying activity;

• you are aware that you’re having difficulty paying attention; and

• you blame the environment for your sorry state (“This task is boring”; “There is nothing to do”).

{ University of Guelph | Continue reading }

art { Picasso, Femme couchée lisant, 1960 }

Linguistics, neurosciences, psychology | October 1st, 2012 12:59 pm

New research traces the dramatic rise in feminine pronouns in books over the past century.

Using the Google Books database, the researchers examined the ratio of male pronouns (he, him, his, himself) to female ones (she, her, hers, herself) in the texts of 1.2 million books published in the U.S. between 1900 and 2008. They suspected feminine references would represent a larger percentage of such words over time, as women gained in power and status.

They were right. But there were periods of regression, and a real shift didn’t occur until the late 1960s.

{ Pacific Standard | Continue reading }

Linguistics, genders | September 19th, 2012 11:54 am

Languages are continually changing, not just words but also grammar. A recent study examines how such changes happen. […]

Historical linguists, who document and study language change, have long noticed that language changes have a sneaky quality, starting small and unobtrusive and then gradually conquering more ground, a process termed ‘actualization’. […]

Consider the development of so-called downtoners – grammatical elements that minimize the force of the word they accompany. Nineteenth-century English saw the emergence of a new downtoner, all but, meaning ‘almost’. All but started out being used only with adjectives, as in her escape was all but miraculous. But later it also began to turn up with verbs, as in until his clothes all but dropped from him. In grammatical terms, that is a fairly big leap, but when looked at closely the leap is found to go in smaller steps. Before all but spread to verbs, it appeared with past participles, which very much resemble both adjectives and verbs, as in her breath was all but gone.

{ Linguistic Society of America }

Linguistics | September 4th, 2012 11:00 am

One definition is that a Type III error occurs when you get the right answer to the wrong question. This is sometimes called a Type 0 error.

{ Graph Pad | Continue reading }

photos { Stephen Shore, American Surfaces, 1972 }

Linguistics, mathematics, photogs | July 17th, 2012 9:37 am

…New York the most linguistically diverse city in the world. […]

While there is no precise count, some experts believe New York is home to as many as 800 languages — far more than the 176 spoken by students in the city’s public schools or the 138 that residents of Queens, New York’s most diverse borough, listed on their 2000 census forms. […]

New York is such a rich laboratory for languages on the decline that the City University Graduate Center is organizing an endangered-languages program. […]

In addition to dozens of Native American languages, vulnerable foreign languages that researchers say are spoken in New York include Aramaic, Chaldic and Mandaic from the Semitic family; Bukhari (a Bukharian Jewish language, which has more speakers in Queens than in Uzbekistan or Tajikistan); Chamorro (from the Mariana Islands); Irish Gaelic; Kashubian (from Poland); indigenous Mexican languages; Pennsylvania Dutch; Rhaeto-Romanic (spoken in Switzerland); Romany (from the Balkans); and Yiddish.

Researchers plan to canvass a tiny Afghan neighborhood in Flushing, Queens, for Ormuri, which is believed to be spoken by a small number of people in Pakistan and Afghanistan. […]

In northern New Jersey, Neo-Aramaic, rooted in the language of Jesus and the Talmud, is still spoken by Syrian immigrants and is taught at Syriac Orthodox churches in Paramus and Teaneck. […] And on Long Island, researchers have found several people fluent in Mandaic, a Persian variation of Aramaic spoken by a few hundred people around the world.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

photo { “Back to the 50′s” car show at the Minnesota State Fair Grounds }

Linguistics, new york | July 2nd, 2012 8:12 am

Linguistics, economics | June 19th, 2012 6:39 am

Many of the great clinicians who studied psychosis in the last two hundred years became famous for their specific nosologic contribution when they sought to define and uncover specific psychotic entities or illnesses. Other clinicians owed their fame to their description of certain original symptoms of psychosis. However, when possible, few of them were able to avoid the temptation to formulate their own nosology, and subsequently engage in scholastic disputes in defending their findings. Insofar as a clinical approach to psychosis implies a high focus on symptomatology, few researchers and clinicians would attempt to formulate a global system to define and explain psychotic symptomatology and the mechanisms for the production of psychotic symptoms. Many of those who did attempt to do so failed because they were unable to reconcile what seemed to be contradictory concepts, or because they often failed to coherently recognize, define and categorize the disparate symptoms of psychosis. However, one clinician was able to succeed. Gaëtan Gatian de Clérambault was able to formulate an exhaustive and coherent system of psychotic symptom categorization. As a result, in retrospect, Clérambault would most likely emerge as one of the most prominent figures of descriptive psychopathology of psychosis.

This French alienist of the early part of the twentieth century was a complex man who was recognized to hold a variety of expertises in many areas. Clérambault is most well known in the Anglo-Saxon literature for his work on the ‘psychose passionelle’ (erotomania) otherwise known as Clérambault’s Syndrome. He also excelled in ethnographic anthropology and his lectures at the Beaux Arts and the Sorbonne in Paris were said to be legendary. However, it is his contribution to psychiatric semeology which would prove to be most fundamental. He was able to establish a coherent system whereby the understanding of the basic characteristics of psychotic symptoms would go in pair with the description of their alleged underlying neural processes. These underlying neural processes would be defined in terms of abnormal behaviors of neural connectivity. Rather than simply drafting an arbitrary listing of symptoms, Clérambault would provide an exhaustive taxonomy of psychotic symptoms based on the description of their most subtle features and nuances. Clérambault’s catalogue of psychotic symptoms is original in the sense that each symptom finds its place within a category defined by either a specific characteristic or a specific predominance of one or several characteristics. He would create groups and subgroups for these symptoms when deemed necessary. These groups would be placed into subcategories which were in turn grouped into larger categories. The main categories would include the sensory, the motor and the mental phenomena. However, the great value of Clérambault’s system is that all the groups, subgroups, subcategories and categories, and therefore all the categorized psychotic symptoms, would be defined by one characteristic common to all, their automatic and autonomous nature.

The psychotic symptoms would thus become referred to as automatisms.

Generally speaking, the notion of automatism is a synonymous concept to that of a very basic category of psychotic symptoms. In fact, aside from delusions, automatisms represent all other psychotic symptoms. However, one of the novelties of Clérambault’s concept is that automatisms can occur in the context of normal or subnormal function, that is in the context of the normal thinking process and the so-called subnormal conditions when the nervous system is strongly challenged. As we will see, within the larger concept of automatism, the boundaries of psychosis and normal function are redefined.

{ Paul Hriso | Continue reading }

French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan attributed his ‘entry into psychoanalysis’ as largely due to the influence of de Clérambault, whom he regarded as his ‘only master in psychiatry.’

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Linguistics, psychology | May 23rd, 2012 3:59 pm

The hypothesis was that people who used particular basic word orders would have more children. Testing this hypothesis directly, basic word order is a significant predictor of the number of children a person has (linear regression, controlling for age, sex, if the person was married, if they were employed their level of education and religion, t-value for basic word order = -18.179, p < 0.00001, model predicts 36% of the variance).

It turns out that speakers of SOV languages have more children than speakers of SVO languages, while speakers with no dominant order have the fewest children on average.

{ Replicated Typo | Continue reading }

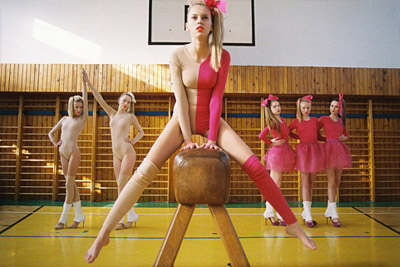

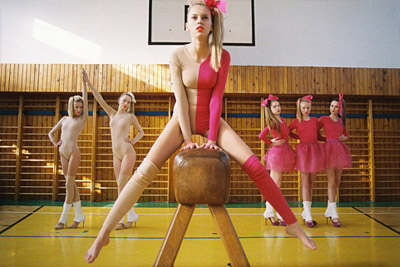

photo { Michal Pudelka }

Linguistics, kids | May 11th, 2012 1:47 pm

If we look at how communication works we find that words and phrases have a great influence on attention. They bring into the consciousness of the listener the concepts that are uttered. This is what meaning is – the concepts that a word or phrase can steer attention towards. This is what communication is – the sharing of attention by two (or more) brains on a sequence of concepts.

So it is not surprising that it is useful to talk to oneself. What we are doing when we self-talk is to steer our consciousness. In recent paper, Lupyan and Swingley look at how self-directed speech affects searching.

{ Thoughts on thoughts | Continue reading }

Linguistics, psychology | May 8th, 2012 10:54 am

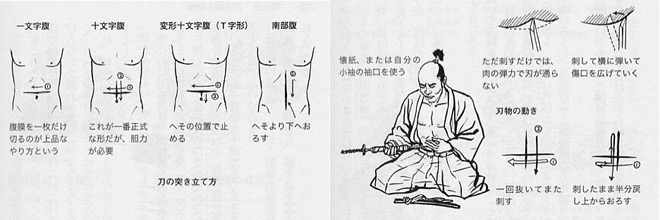

Many crimes are generally performed by using language. Among them are solicitation, conspiracy, perjury, threatening, and bribery. In this chapter, we look at these crimes as acts of speech, and find that they have much in common – and a few interesting differences. For one thing, they involve different acts of speech, ranging from promises to orders. For another, most language crimes can be committed through indirect speech. Few criminals will say, “I hereby offer you a bribe,” or “I hereby engage you to kill my spouse.” Thus, many of the legal battles involve the extent to which courts may draw inferences of communicative intent from language that does not literally appear to be criminal. Yet the legal system draws a line in the sand when it comes to perjury, a crime that can only be committed through a direct fabrication. We provide a structured discussion of these various crimes that should serve to explain the similarities and difference among them.

{ SSRN | Continue reading }

Linguistics, ideas, law | April 24th, 2012 7:54 am

Would you make the same decisions in a foreign language as you would in your native tongue? It may be intuitive that people would make the same choices regardless of the language they are using, or that the difficulty of using a foreign language would make decisions less systematic. We discovered, however, that the opposite is true: Using a foreign language reduces decision-making biases. (…) We propose that these effects arise because a foreign language provides greater cognitive and emotional distance than a native tongue does.

{ SAGE | Continue reading }

Linguistics, psychology | April 22nd, 2012 8:23 am

‘Quantified pure existentials’ are sentences (e.g., ‘Some things do not exist’) which meet these conditions: (i) the verb EXIST is contained in, and is, apart from quantificational BE, the only full (as against auxiliary) verb in the sentence; (ii) no (other) logical predicate features in the sentence; (iii) no name or other sub-sentential referring expression features in the sentence; (iv) the sentence contains a quantifier that is not an occurrence of EXIST.

Colin McGinn and Rod Girle have alleged that stan- dard first-order logic cannot adequately deal with some such existen- tials. The article defends the view that it can.

{ Disputatio | PDF }

unrelated { A few new words: Doxing, Errbody, Grok, Muppies… }

Linguistics, ideas | April 18th, 2012 10:47 am

In psychology, this phenomenon is called “gaslighting,” a term that has its origins in a 1938 play (and a 1940 film) called Gas Light, where a man leads his wife to believe that she is insane in order to steal from her. (…)

A classic example of psychological gaslighting is the following: Spouse A has an extramarital affair and tries to cover it up. Spouse B finds a suspicious text message in A’s phone and expresses concern to A. A then accuses B of being paranoid, and this pattern repeats every time B raises concerns. Eventually B begins to question his or her own perceptions.

{ Psych Your Mind | Continue reading }

image { Steven Pippin }

Linguistics, psychology, relationships | April 16th, 2012 4:02 pm

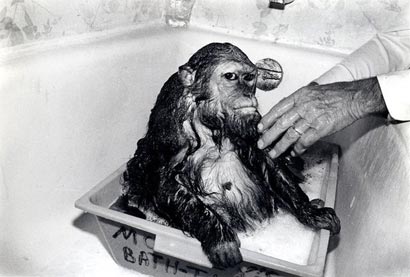

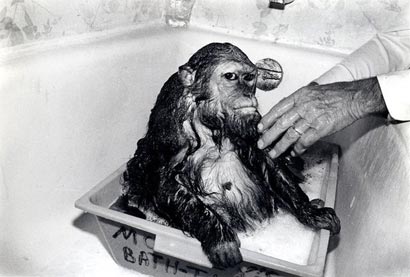

Baboons have mastered one of the basic elements of reading - identifying the difference between sequences of letters that make up actual words from nonsense sequences.

Although the animals have no linguistic skills, they were able to classify a four-letter sequence as either a real word or a random sequence. These findings challenge the long-held notion that the ability to recognise words in this way - as combinations of objects that appear visually in certain sequences - is fundamentally related to language.

It now appears that when humans read, we are partly drawing on an ancient ability, predating the evolution of our own species.

Linguists agree that language is needed during reading, but at which stage language becomes a necessity has come under debate. Past research has shown that animals have the ability to discriminate letters from one another, but previously experts thought the ability to recognise words was dependent on an ability to understand language.

{ Cosmos | Continue reading }

photo { Robin Schwartz }

Linguistics, animals, science | April 13th, 2012 8:08 am

Computer scientists have analysed thousands of memorable movie quotes to work out why we remember certain phrases and not others. (…)

They then asked individuals who had not seen the films to guess which of the two lines was the memorable one. On average, people chose correctly about 75 per cent of the time, confirming the idea that the memorable features are inherent in the lines themselves and not the result of some other factor, such as the length of the lines or their location in the film. (…)

They then compared the memorable phrases with a standard corpus of common language phrases taken from 1967, making it unlikely to contain phrases from modern films. (…)

The phrases themselves turn out to be significantly distinctive, meaning they’re made up of combinations of words that are unlikely to appear in the corpus. By contrast, memorable phrases tend to use very ordinary grammatical structures that are highly likely to turn up in the corpus.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

Linguistics, showbiz | April 3rd, 2012 12:01 pm