We all naturally think that our perception of the external world is accurate and correct: why else would it work so consistently for us? By and large, that view is quite correct. The model we have of the world works because our brains constantly make predictions about how the world behaves and when we test it by our actions, the errors are detected and the model is improved. This correction means that we are always improving our model of the physical world, making it more useful.

Chris Frith, a Professor of Neuropsychology, explains how our brain filters out a vast amount of what we perceive. Our vision is constantly corrected by the brain to allow for everything from indistinct features on the edge of our field of view, through to filling in the blind spot on our retinas so we see complete scenes. Our brain routinely compensates for inadequate perception by filling in the details by prediction.

{ Blogcritics | Continue reading }

photo { Cassander Eeftinck Schattenkerk }

related { How your brain creates the fourth dimension. }

brain, science | November 13th, 2009 9:32 am

Researchers at the Swedish medical university Karolinska Institutet have discovered a mechanism that controls the brain’s ability to create lasting memories. In experiments on genetically manipulated mice, they were able to switch on and off the animals’ ability to form lasting memories by adding a substance to their drinking water.

The ability to convert new sensory impressions into lasting memories in the brain is the basis for all learning. Much is known about the first steps of this process, those that lead to memories lasting a few hours, whereby altered signalling between neurons causes a series of chemical changes in the connections between nerve fibers, called synapses. However, less is understood about how the chemical changes in the synapses are converted into lasting memories stored in the cerebral cortex.

A research team at Karolinska Institutet has now discovered that signalling via a receptor molecule called nogo receptor 1 (NgR1) in the nerve membrane plays a key part in this process.

{ Karolinska Institutet | Continue reading }

related { Traumatic memories can be erased. }

brain, science | November 13th, 2009 9:30 am

Advances in technology have revealed that our brains are far more altered by experience or training than was thought possible. The memory-storing hippocampus region of the brain in London taxi drivers is bigger, and the auditory areas of musicians more developed, than average. Even learning to juggle can result in a certain amount of rewiring of the brain.

So the Lord Chief Justice’s suggestion that a lifetime spent on the internet will alter the way we think and process information is well founded. But whether these changes will enhance or degrade our powers of imagination, recall and decision-making has divided scientists.

Baroness Greenfield, director of the Royal Institution, was among the first to warn that today’s children may grow up with short attention spans and no imagination. Others suggest that the abandonment of books means people will lose the ability to follow a plot from start to finish. However, as yet little or no evidence has emerged to support these fears.

Short-term studies have, if anything, shown internet use to have a positive impact on our mental powers.

A study published this week, for instance, revealed that when “internet naive” adults carried out web searches every day for two weeks, it boosted the activity in brain areas linked to decision-making and working memory.

The reality is likely to be a trade-off: certain abilities will be enhanced at the expense of others. It could be that browsing through the vast quantities of information on the web leaves people better equipped to filter out the irrelevant and focus on the important.

Meanwhile, people may get worse at keeping the bigger picture in mind. Only a long-term psychological study will provide a definitive picture of how internet use affects cognition.

{ Times }

artwork { Peter Atkins, Last Fuel For 1000km, 2009 }

brain, technology | October 30th, 2009 9:04 am

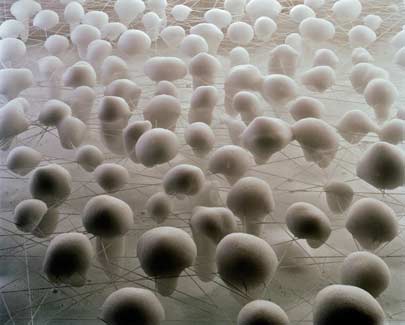

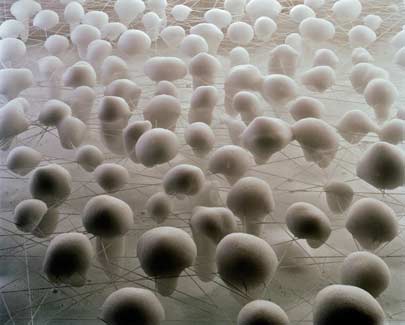

In the mid-1800s researchers discovered cells in the brain that are not like neurons (the presumed active players of the brain) and called them glia, the Greek word for “glue.” Even though the brain contains about a trillion glia—10 times as many as there are neurons—the assumption was that those cells were nothing more than a passive support system. Today we know the name could not be more wrong.

Glia, in fact, are busy multitaskers, guiding the brain’s development and sustaining it throughout our lives. Glia also listen carefully to their neighbors, and they speak in a chemical language of their own. Scientists do not yet understand that language, but experiments suggest that it is part of the neurological conversation that takes place as we learn and form new memories. (…)

All neurons have certain characteristic attributes: axons, synapses, and the ability to produce electric signals. As scientists peered at bits of brain under their microscopes, though, they encountered other cells that did not fit the profile. When impaled with electrodes, these cells did not produce a crackle of electric pulses. If electricity was the language of thought, then these cells were mute. German pathologist Rudolf Virchow coined the name glia in 1856, and for well over a century the cells were treated as passive inhabitants of the brain.

At least a few scientists realized that this might be a hasty assumption. (…) Today the mystery of glia is partially solved. Biologists know they come in several forms. One kind, called radial glia, serve as a scaffolding in the embryonic brain. Neurons climb along these polelike cells to reach their final location. Another kind of glia, called microglia, are the brain’s immune system. They clamber through the neurological forest in search of debris from dead or injured cells. A third class of glia, known as Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes, form insulating sleeves around neurons to keep their electric signals from diffusing.

{ Discover | Continue reading }

brain | October 17th, 2009 3:25 pm