photogs

Avoid hangovers, stay drunk

{ The artworks presented are typified by their transformation of a functioning musical composition or mapping document from a sound-based performance into a work of visual art. | Render Visible | 29 Wythe Ave, Brooklyn, NY 11211 | Reception: Friday, October 5, until October 28 | Photo: Hannah Whitaker }

Are we really sure? Can a love that lasted for so long still endure?

{ Corinne May Botz, Apartment No.2, Brooklyn, New York | Haunted Houses is a long-term project in which I photographed and collected oral ghosts stories in over eighty haunted sites throughout the United States. | image gallery + listen to ghost stories | Alice Austen House Museum, Staten Island, NY until Dec. 30, 2012 }

We choose to go to the moon and do the other things

The rise of social photography means that we are now seeing images all the time, millions of them, billions, many of which are manipulated with the same easy algorithms, the same tiresome vignetting, the same dank green wash. […]

All bad photos are alike, but each good photograph is good in its own way. The bad photos have found their apotheosis on social media, where everybody is a photographer and where we have to suffer through each other’s “photography” the way our forebears endured terrible recitations of poetry after dinner. Behind this dispiriting stream of empty images is what Russians call poshlost: fake emotion, unearned nostalgia. According to Nabokov, poshlost “is not only the obviously trashy but mainly the falsely important, the falsely beautiful, the falsely clever, the falsely attractive.”

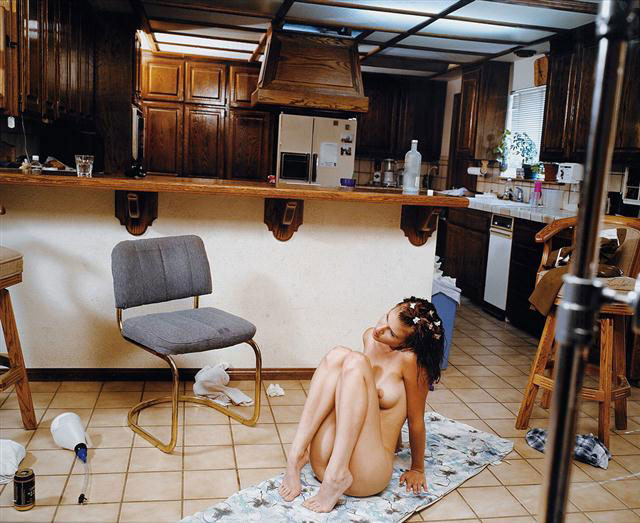

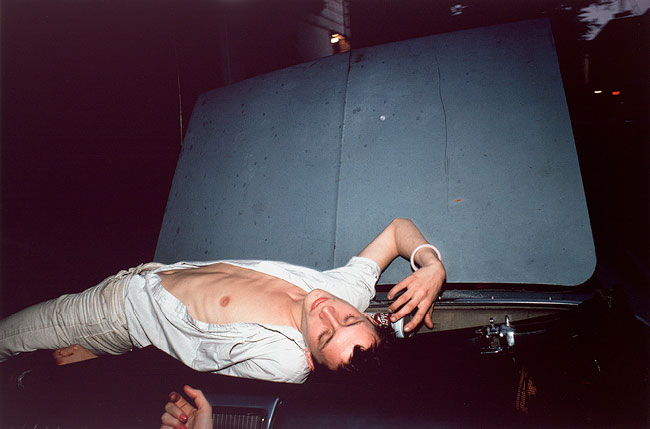

photo { Nan Goldin }

A queer kind of medium, the mind

When we’re making a snap judgement about a fact, the mere presence of an accompanying photograph makes us more likely to think it’s true, even when the photo doesn’t provide any evidence one way or the other. In the words of Eryn Newman and her colleagues, uninformative photographs “inflate truthiness.” […]

The researchers can’t be sure: “We speculate that nonprobative photos and verbal information help people generate pseudo evidence,” they said.

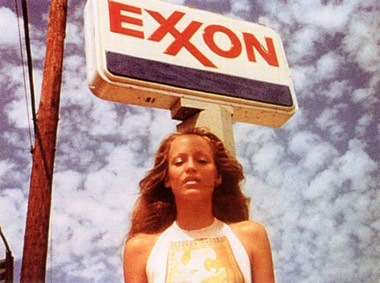

photo { 16 year old Jerry Hall on a road trip, photographed by Antonio Lopez }

Chemistry is the study of matter, but I prefer to see it as the study of change. It is growth, then decay, then transformation.

Women with resources are slower to marry and remarry, and are more likely to cohabitate with a partner. Women are also more likely to purchase homes on their own, build female friendships, and engage in community-based work. As women increase their earnings and status, women are also more open to date outside their ethnicity.

I hate to advocate drugs, alcohol, violence, or insanity to anyone, but they’ve always worked for me

“I’ve always been interested in overdoses and addictions,” she says. […]

“I’m obsessed with cocaine overdoses in British society. They call it the ‘white death.’” […]

“I think my dust dealer’s in jail or something. Where’s my cellphone?”

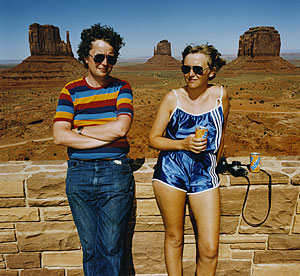

photo { Ernst Haas }

‘Yeah whatever, life.’ –Samantha Hinds

Ontological Nihilism is the radical-sounding thesis that there is nothing at all. Almost nobody believes it. But this does not make it philosophically uninterest- ing: we can come to better understand a proposition by studying its opposite. By better understanding what Ontological Nihilism is — and what problems beset it — we can better understand just what we say when we say that there are some things.

photo { Johnny Marchisi }

Oowah oowah is my disco call

At 12 or 13, we started taking buses to New York City and going to raves. My friends and I discovered this underground culture and adopted this great style that was still foreign to our small upstate community. At the height of the rave scene, I could have described myself as a “polo” raver. I’d wear 60-inch wide jeans called Aura’s E, which was a brand by this girl in Long Island named Aura. I shaved my eyebrows completely off, pierced everything on my face, put platforms on my running sneakers… I’d work day and night in the mall upstate so that I could buy my rave tickets and take bus trips to get all the cool clothes in the city. I found out about everything from shops like Liquid Sky and Satellite Records––they would put flyers out and you had to call hotlines to find out all the rave info. All the great mixtapes were sold at the stores too. It was a real beautiful time to be a teenager and so close to NYC.

And imagine such an enormous mass of countless particles of sand multiplied as often as there are leaves in the forest, drops of water in the mighty ocean, feathers on birds, scales on fish, hairs on animals, atoms in the vast expanse of the air

The sorites paradox is a paradox that arises from vague predicates.

The paradox of the heap is an example of this paradox which arises when one considers a heap of sand, from which grains are individually removed. Is it still a heap when only one grain remains? If not, when did it change from a heap to a non-heap?

quote { James Joyce, A Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man, 1916 }

What went forth to the ends of the world to traverse not itself. God, the sun, Shakespeare, a commercial traveller, having itself traversed in reality itself, becomes that self.

What are some things that money can’t buy?

Per the answers given below, in no particular order:

Health, strength, athleticism

Unconditional love

Time

A clean conscience or genuine serenity

Genuine human companionship

A natural good night’s sleep

Rain

Taste/Class/Character

Artistic ability

Natively high water pressure (debatable)

[…]

Here’s one thing that most people probably won’t realize money can’t buy: natively high water pressure.

related { How is being a billionaire better than being a millionaire? }

photo { William Gedney }

Always be yourself. Unless you can be a Unicorn. Then always be a Unicorn.

{ Barbra Streisand by Richard Avedon, 1965 | More: Vogue, 1966 }

Loneliness has followed me my whole life. Everywhere. In bars, in cars, sidewalks, stores, everywhere. There’s no escape. I’m God’s lonely man.

If you’re unusually insightful and perceptive, like me, you may have noticed that boastfulness is increasingly socially acceptable these days. […]

With so many more channels through which to manipulate one’s public image, it’s not especially surprising that we are tempted to present ourselves as positively as possible. The filters of social media make things worse. A network such as Twitter is designed precisely to connect you with exactly the kinds of people who don’t mind your boasts, while those who might keep you in check won’t follow you in the first place: your audience thus serves as an army of enablers, applauding your self-applause. […]

But, as the Wall Street Journal noted this week, in a worried piece headlined Are We All Braggarts Now?, the causes may be economic, too. In the most competitive job market in recent memory, the pressure to portray yourself as better than everyone else is intense. Predictably, there’s neuroscientific evidence to undergird all this: self-disclosure activates the same brain regions as eating or sex, according to research by Harvard neuroscientists.

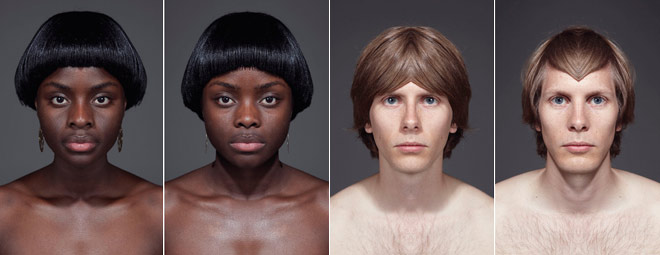

photo { Charlie Engman }

It has been established that persons who have recently died have been returning to life and committing acts of murder

{ Renhui Zhao | Martin Honert }

‘There is another world, and it is inside this one.’ –Paul Éluard

The need for closure is an individual’s motivation to find an answer to a question and the degree to which they can tolerate the uncertainty of not knowing an answer to the question. People high in need for closure see the world as black or white, and strive for quick resolutions to problems. They are fearful of not knowing. People low in the need for closure are more tolerant of uncertainty, though all humans have a basic need for certainty and predictability.

One of the major themes to David DiSalvo’s “What Makes Your Brain Happy and Why You Should Do the Opposite” is that although our brain craves certainty, oftentimes things are not as they seem. He advocates taking more time and being aware of our evolutionarily hard-wired cognitive processes and their strengths and limitations.

People have the basic need to feel that they are right, or certain, in their evaluation of the environment. This certainty can be accomplished by seeking out information in only a small segment of the environment; this tendency is called the selectivity bias. Rather than considering all the available information, people pick and choose to what they attend. When we selectively attend to information that confirms what we already believe, we fall prey to the confirmation bias. If information that could potentially discredit a belief is ignored, the person can maintain that their beliefs are correct.

[…]

We live in the present. We may think that we are future-oriented but the research on discounting the future tells otherwise. Humans evolved to desire immediate awards and avoid immediate threats, so it can be difficult to place ourselves into the future and determine what our lives will be like then.

photo { Asger Ladefoged }

You should have seen long John’s eye

In general, the more different is the new environment from the old, the better it is to start over. Rigid things are fragile, in that they break when you try to bend them far.

This suggests that designed systems tend to get irreversibly fragile as they adapt to specific environments. When context changes greatly, it is usually easier to build new systems from “scratch,” than to un-adapt systems designed for other contexts. Software tends to “rot“, for example. […]

Today I’m focused on this being bad news for the feasibility of immortality, at least for human-like creatures. You see, our minds seem designed to adapt to the environment in which we grow up, via youthful plasticity transitioning to elderly rigidity. For example, we are great at learning languages when young, and terrible when old. We are similarly receptive when young to new ways to categorize and conceive of things, but once we have often used particular ways, we find it harder to understand and use alternatives.

The brains of most animals peak in functionality during their key reproductive years, and do worse both before and after. Short lived animals peak sooner than long lived animals. Some of the early rise is due to learning, and some of later decline is due to the decline of individual cells and connections. Some of this pattern may even be due to an explicit plan to turn up some dials on plasticity early on, and then turn down those dials later. But I think another important part of this rise and fall is due to a general robust tendency for adapted systems to slide from plasticity to rigidity.

photo { Joel Meyerowitz }