sleep

Recent research on circadian rhythms has suggested a reliable method to reduce or even completely prevent jet lag. […]

Circadian rhythms are the roughly 24-hour biological rhythms that drive changes within humans and most other organisms. […] Usually these rhythms align with the environment’s natural light and dark cycle. […]

Whether circadian rhythms align with the environment is determined by factors such as exercise, melatonin, and light. Bright light exposure is the most powerful way to cause a phase shift — an advance or delay in circadian rhythms. Light in the early morning makes you wake up earlier (“phase advance”); light around bed time makes you wake up later (“phase delay”).

This simple insight can be used to minimise jet lag. For example, Helen Burgess and colleagues from the Rush University Medical Center in Chicago studied whether jet lag could be prevented by phase shifting before departing. After three days of light exposure in the morning, the participants’ circadian rhythms shifted by an average of 2.1 hours. This means they would feel less jet lagged, and would be fully adjusted to the new time zone around two days earlier. Several field studies have reached similar conclusions.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

Narcolepsy is a disorder of the immune system where it inappropriately attacks parts of the brain involved in sleep regulation. The result is that affected people are not able to properly regulate sleep cycles meaning they can fall asleep unexpectedly, sometimes multiple times, during the day.

One effect of this is that the boundary between dreaming and everyday life can become a little bit blurred and a new study by sleep psychologist Erin Wamsley aimed to see how often this occurs and what happens when it does.

{ Mind Hacks | Continue reading }

related { The U.S. is addicted to advice. Americans honestly believe that someone out there knows how to fix all our problems. }

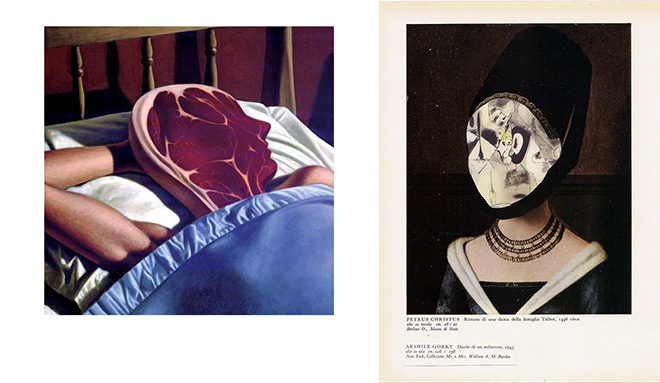

art { Nathan James }

guide, sleep | February 10th, 2014 10:20 am

The placebo effect is known far and wide. Give somebody a sugar pill, tell them it’s aspirin, and they’ll feel better. What’s less well-known is that there’s evidence of the placebo effect in domains that go beyond the commonly known medical scenarios.

One study found that hotel maids who were told their work was good exercise later scored higher than a control group on a range of health indicators. Another study found that when participants were told athletes had excellent vision, they demonstrated better vision when doing a more-athletic activity relative to a less-athletic activity. Many studies have also shown that placebo caffeine can have an impact. In one experiment caffeine placebos improved cognitive performance among participants who were in the midst of 28 hours of sleep deprivation.

Given that caffeine placebos can mitigate the effects of sleep deprivation, Christina Draganich and Kristi Erdal of Colorado College decided to take the logical next step and investigate whether the effects of sleep deprivation could be influenced by perceptions about sleep quality. In other words, could making people think their sleep quality was better or worse influence the cognitive effects of sleep?

{ Peer-reviewed by my neurons | Continue reading }

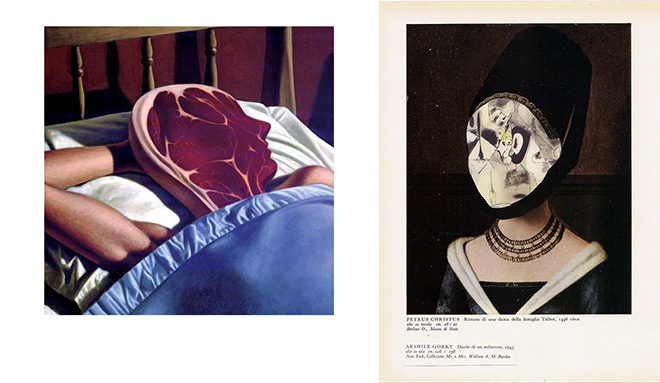

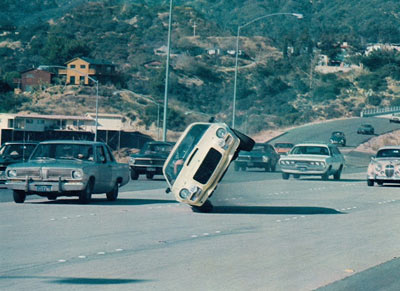

images { 1. David Cutter | 2 }

food, drinks, restaurants, psychology, sleep | January 16th, 2014 8:06 am

In the early 1990s, psychiatrist Thomas Wehr conducted an experiment in which a group of people were plunged into darkness for 14 hours every day for a month.

It took some time for their sleep to regulate but by the fourth week the subjects had settled into a very distinct sleeping pattern. They slept first for four hours, then woke for one or two hours before falling into a second four-hour sleep. […]

In 2001, historian Roger Ekirch of Virginia Tech published a seminal paper, drawn from 16 years of research, revealing a wealth of historical evidence that humans used to sleep in two distinct chunks. […]

Much like the experience of Wehr’s subjects, these references describe a first sleep which began about two hours after dusk, followed by waking period of one or two hours and then a second sleep. […] During this waking period people were quite active. They often got up, went to the toilet or smoked tobacco and some even visited neighbours. Most people stayed in bed, read, wrote and often prayed. Countless prayer manuals from the late 15th Century offered special prayers for the hours in between sleeps.

And these hours weren’t entirely solitary - people often chatted to bed-fellows or had sex.

A doctor’s manual from 16th Century France even advised couples that the best time to conceive was not at the end of a long day’s labour but “after the first sleep”, when “they have more enjoyment” and “do it better”.

Ekirch found that references to the first and second sleep started to disappear during the late 17th Century.

{ BBC | Continue reading }

flashback, sleep | April 21st, 2013 11:51 am

The risk of waking from a general anaesthetic while under the surgeon’s knife is extremely small - about one in 15,000 - research reveals.

Out of nearly 3 million operations in 2011 there were 153 reported cases. […] A third - 46 in total - were conscious throughout the operation.

{ BBC | Continue reading }

The incidence of accidental awareness during general anaesthesia (AAGA) is reported by several studies to be surprisingly high, in the range of 1–2 per 1000 general anaesthetics administered. These studies employ a direct patient questionnaire (usually repeated three times over a period of up to 30 days postoperatively) known as the ‘Brice protocol.’ It is also reported that a high proportion of patients experiencing AAGA suffer psychological problems including posttraumatic stress disorder. There are in fact very few studies reporting an incidence of AAGA much lower than this, an exception being that of Pollard et al., who found an incidence of 1:14 500. However, their methods might be criticised as they administered the questionnaire only twice over a 48-h period, which might only detect two thirds of cases . Anecdotally, anaesthetists do not perceive the incidence of AAGA to be so high. A small Japanese study found that only 21 of 172 practitioners had known of an incident of AAGA under their care, with an overall incidence of just 1:3500. In a larger UK survey of over 2000 consultants, Lau et al. reported that anaesthetists estimated the incidence to be approximately 1:5000, similar to the estimated incidence reported previously by 220 Australian anaesthetists of between 1:5000 and 1:10 000.

{ Anaesthesia/Wiley | Continue reading }

drugs, health, incidents, sleep | March 27th, 2013 3:08 pm

Fall asleep in the wrong position, and acid slips into the esophagus, a recipe for agita and insomnia.

Doctors recommend sleeping on an incline, which allows gravity to keep the stomach’s contents where they belong. But sleeping on your side can also make a difference — so long as you choose the correct side. Several studies have found that sleeping on the right side aggravates heartburn; sleeping on the left tends to calm it.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

related { Those who have a tendency to migrate to the left of a double bed are apparently happier than their ‘right’ counterparts }

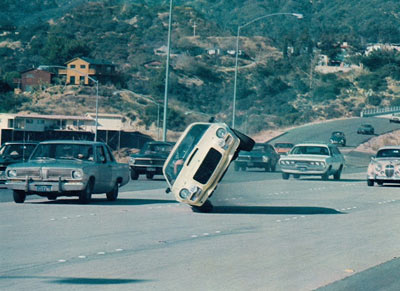

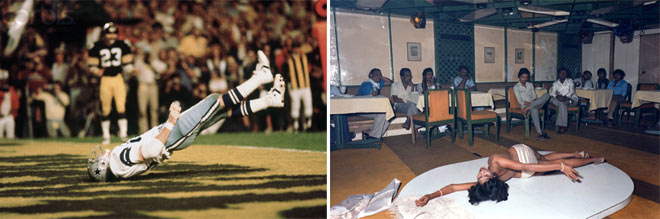

photos { Wally McNamee | Mitch Epstein }

health, sleep | March 22nd, 2013 12:29 pm

Jon M at Sociological Speculation reports:

…new drugs such as Modafinil appear to vastly reduce the need for sleep without significant side effects (at least so far). Based on reports from users, it seems that people could realistically cut their sleep requirements to as few as 2.5 hours a night without a decrease in mental acuity.

He notes that people would probably work more, and wonders whether…

…these pills would amount to an increase in the labour supply and cause a fall in hourly wages or unemployment.

Normal microeconomics makes the right answer obvious: A rise in supply pushes down the price of work, so wages will fall. But normal microeconomics only takes you so far: to get at dynamics and interdependence you need some kind of macroeconomics, a tool for seeing the big picture.

So here’s what probably happens when drugs make it easier to work more hours: All those extra work hours make capital more valuable, since your assembly line, your delivery truck, your call center can now all produce more output per machine.

What happens when something gets more valuable? People try to accumulate more of it. And what happens when the economy accumulates more capital? All those extra machines probably make workers more productive, boosting labor demand and therefore raising wages.

{ Garett Jones/EconLog | Continue reading }

economics, sleep | January 15th, 2013 1:46 pm

For a small group of people—perhaps just 1% to 3% of the population—sleep is a waste of time.

Natural “short sleepers,” as they’re officially known, are night owls and early birds simultaneously. They typically turn in well after midnight, then get up just a few hours later and barrel through the day without needing to take naps or load up on caffeine.

They are also energetic, outgoing, optimistic and ambitious, according to the few researchers who have studied them. The pattern sometimes starts in childhood and often runs in families. […]

Out of every 100 people who believe they only need five or six hours of sleep a night, only about five people really do, Dr. Buysse says. The rest end up chronically sleep deprived, part of the one-third of U.S. adults who get less than the recommended seven hours of sleep per night. […]

Dr. Fu was part of a research team that discovered a gene variation, hDEC2, in a pair of short sleepers in 2009. They were studying extreme early birds when they noticed that two of their subjects, a mother and daughter, got up naturally about 4 a.m. but also went to bed past midnight.

Genetic analyses spotted one gene variation common to them both. The scientists were able to replicate the gene variation in a strain of mice and found that the mice needed less sleep than usual, too.

{ WSJ | Continue reading }

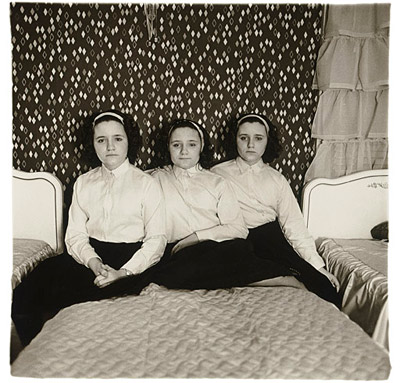

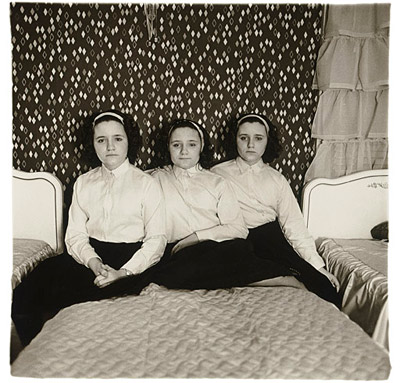

photo { Diane Arbus }

genes, sleep | October 8th, 2012 7:19 am

Large-scale surveys indicate that on average people spend more time sleeping than working. […]

Negative effects of sleep deprivation are especially problematic in contemporary organizations, given recent research indicating that sleep has decreased at a rate of about 5 minutes per decade for the past three decades.

A large-scale study indicates that 29.9% of Americans get less than 6 hours per day; for those in management and enterprises, 40.5% get less than 6 hours. Large- scale studies from Korea, Finland, Sweden, and England also indicate high proportions of people functioning on low quantities of sleep or poor sleep quality. Probably as a result of insufficient sleep, 29% of Americans report extreme sleepiness or falling asleep at work in the past month. Thus, across many countries, there is an abundance of employees who work after a short night of sleep or poor quality sleep. […]

Organizational psychology researchers have recently begun to investigate this topic, highlighting effects of low sleep quantity and poor sleep quality on job satisfaction, unethical behavior, workplace deviance, lack of innovative thinking, and high risk of work injuries.

{ SAGE | PDF }

art { Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1538 }

economics, health, sleep | September 28th, 2012 2:38 pm

Networks of muscles, of brain cells, of airways and lungs, of heart and vessels operate largely independently. Every couple of hours, though, in as little as 30 seconds, the barriers break down. Suddenly, there’s synchrony. All the disjointed activity of deep sleep starts to connect with its surroundings. Each network joins the larger team. This change, marking the transition from deep to light sleep, has only recently been understood in detail. […]

Similar syncing happens all the time in everyday life. Systems of all sorts constantly connect. Bus stops pop up near train stations, allowing commuters to hop from one transit network to another. New friends join your social circle, linking your network of friends to theirs. Telephones, banks, power plants all come online — and connect online.

A rich area of research has long been devoted to understanding how players — whether bodily organs, people, bus stops, companies or countries — connect and interact to create webs called networks. An advance in the late 1990s led to a boom in network science, enabling sophisticated analyses of how networks function and sometimes fail. But more recently investigators have awakened to the idea that it’s not enough to know how isolated networks work; studying how networks interact with one another is just as important. Today, the frontier field is not network science, but the science of networks of networks. […]

Findings so far suggest that networks of networks pose risks of catastrophic danger that can exceed the risks in isolated systems. A seemingly benign disruption can generate rippling negative effects. Those effects can cost millions of dollars, or even billions, when stock markets crash, half of India loses power or an Icelandic volcano spews ash into the sky, shutting down air travel and overwhelming hotels and rental car companies. In other cases, failure within a network of networks can mean the difference between a minor disease outbreak or a pandemic, a foiled terrorist attack or one that kills thousands of people.

{ ScienceNews | Continue reading }

ideas, networks, science, sleep | September 13th, 2012 5:46 am

Sometime after 2 A.M. one Sunday morning in May 1987, Kenneth James Parks, then 23, left his house in a Toronto suburb and drove 23 kilometers to the apartment of his wife’s parents. He got out of the car, pulled a tire iron out of the trunk and let himself into the older couple’s home with a key they had given him. Once inside, he struggled with and choked his father-in-law, Dennis Woods, until the older man fell unconscious and then struggled with and beat his mother-in-law, Barbara Ann Woods, stabbing her to death with a knife from her kitchen.

Parks then got back into his car, drove to a nearby police station and announced to the startled officers on duty, “I think I have killed some people.” For several hours before the Toronto man left his home, however, and throughout the course of the attack, Parks was asleep and therefore not criminally responsible for his actions, according to five doctors and the defense lawyer at his 1988 trial for the murder of Barbara Ann and the attempted murder of Dennis. After deliberating for nine hours, the jury agreed and Parks was set free.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

horror, incidents, sleep | August 23rd, 2012 2:04 pm

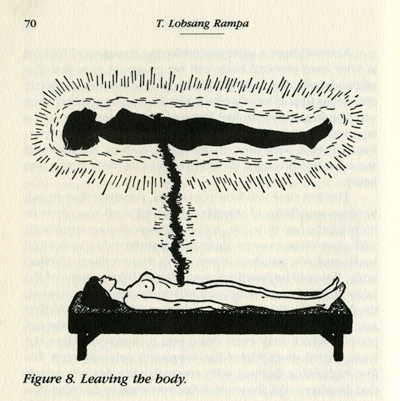

sleep, technology | June 11th, 2012 1:12 pm

For some people with insomnia, the real reason they can’t fall asleep may be a fear of the dark, a small new study suggests.

93 undergraduate students […] 46 percent of the poor sleepers were afraid of the dark, whereas 26 percent of the good sleepers seemed to have this fear. […]

“We can treat this fear,” she said. “We can get people accustomed to the dark so they won’t have that added anxiety that contributes to their insomnia.”

{ LiveScience | Continue reading }

psychology, sleep | June 11th, 2012 11:20 am

The settings for a person’s biological clock might provide clues to when, during the day, he or she will be more active. What’s more, these same settings could be linked to what time of day a person might die, a new study finds.

Understanding the biological basis of these built-in, or circadian, clocks “could lead to products that eventually allow us to shift the clock forwards or backwards,” says Philip De Jager, a neurologist with Harvard Medical School in Boston. He and his colleagues describe their work online April 26 in Annals of Neurology.

Being able to alter these clocks could prove useful for shift workers, such as pilots, who might face trouble working against their intrinsic daily rhythms, De Jager adds. And patients can be better cared for if doctors know what times of day are most critical.

Previously, scientists have shown that many genes are involved in regulating people’s inherent daily wake and sleep patterns. Disruptions to this natural circadian rhythm are often linked to serious health conditions, including diabetes.

{ ScienceNews | Continue reading }

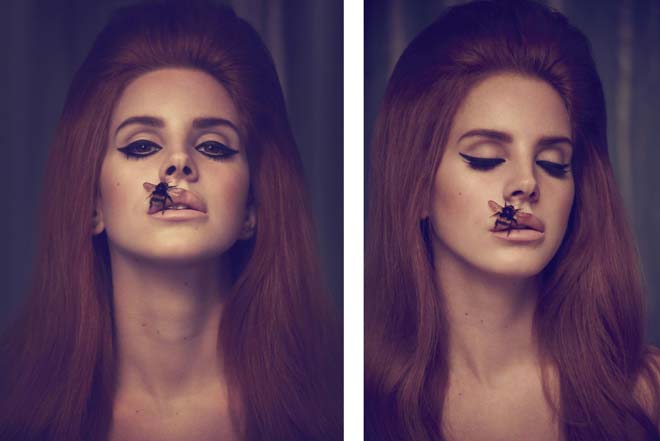

photo { Sean and Seng }

genes, health, sleep | May 15th, 2012 5:38 am

A new study suggests that, by disrupting your body’s normal rhythms, your alarm clock could be making you overweight.

The study concerns a phenomenon called “social jetlag.” That’s the extent to which our natural sleep patterns are out of synch with our school or work schedules. Take the weekends: many of us wake up hours later than we do during the week, only to resume our early schedules come Monday morning. It’s enough to make your body feel like it’s spending the weekend in one time zone and the week in another. […]

Previous work with such data has already yielded some clues. “We have shown that if you live against your body clock, you’re more likely to smoke, to drink alcohol, and drink far more coffee,” says Roenneberg. […]

The researchers also found that people of all ages awoke and went to bed an average of 20 minutes later between 2002 and 2010. Work and school times have remained the same, meaning that social jetlag has increased during this period.

{ Science | Continue reading }

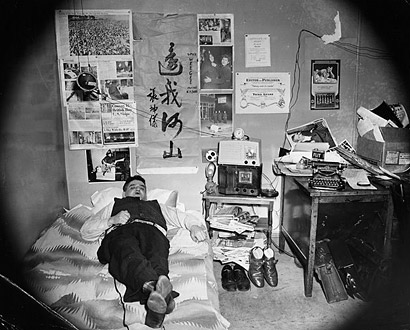

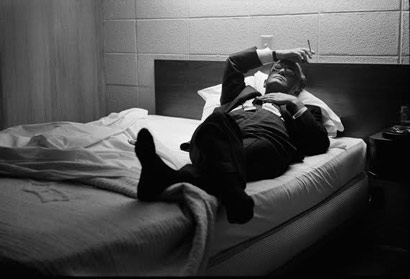

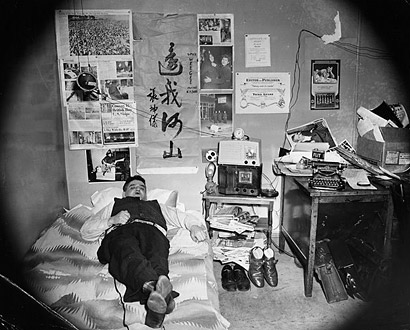

photo { Weegee in his apartment, police radio by his bedside }

health, science, sleep, time | May 11th, 2012 1:58 pm

The ‘body clock’ or circadian rhythms controls things like alertness, sleep patterns, appetite and hormones, and travelling across time zones or working nights can disturb it. […]

The researchers found that two nuclear receptors (receptors that sense hormones), called REV-ERB-α and REV-ERB-β, control the circadian expression of core circadian clock and lipid homeostatic gene networks. Not getting enough sleep puts you at increased risk of obesity, diabetes and related metabolic disorders.

{ Genome Engineering | Continue reading }

genes, health, hormones, sleep | May 8th, 2012 9:49 am

After a busy week with short nights, many use the weekend to make up for lost hours of sleep. Not a healthy habit, says researcher Paulien Barf. On the long run it could result into the development of obesity or even diabetes. (…) Previous studies have shown that sleeping to recover from sleep shortage is of importance for a variety of physiological processes.

{ United Academics | Continue reading }

photo { Lee Friedlander, Nude, 1980 }

health, sleep | May 4th, 2012 6:02 am

Albert Tirrell and Mary Bickford had scandalized Boston for years, both individually and as a couple, registering, as one observer noted, “a rather high percentage of moral turpitude.” Mary, the story went, married James Bickford at 16 and settled with him in Bangor, Maine. They had one child, who died in infancy. Some family friends came to console her and invited her to travel with them to Boston. Mary found herself seduced by the big city. (…)

James came to Boston at once, found Mary working in a house of ill repute on North Margin Street and returned home without her. She moved from brothel to brothel and eventually met Tirrell, a wealthy and married father of two. He and Mary traveled together as man and wife, changing their names whenever they moved, and conducted a relationship as volatile as it was passionate; Mary once confided to a fellow boarder that she enjoyed quarreling with Tirrell because they had “such a good time making up.” (…)

Choate kept that case in mind while plotting his defense of Tirrell, and considered an even more daring tactic: contending that Tirrell was a chronic sleepwalker. If he killed Mary Bickford, he did so in a somnambulistic trance and could not be held responsible.

{ Smithsonian | Continue reading }

photo { Linus Bill }

incidents, law, relationships, sleep | May 2nd, 2012 7:43 am

Some scientists argue that the purpose of sleep may not be restorative. In fact, they argue that the very question “why do we sleep?” is mistaken, and that the real question should be “why are we awake?” (…)

The world record for going without sleep is eleven days.

{ BBC | Continue reading }

photo { Adrienne Grunwald }

photogs, sleep, theory | April 24th, 2012 12:55 pm

Both scientists and artists have suggested that sleep facilitates creativity, and this idea has received substantial empirical support. In the current study, we investigate whether one can actively enhance the beneficial effect of sleep on creativity by covertly reactivating the creativity task during sleep.

Individuals’ creative performance was compared after three different conditions: sleep-with-conditioned-odor; sleep-with-control-odor; or sleep-with-no-odor. In the evening prior to sleep, all participants were presented with a problem that required a creative solution. In the two odor conditions, a hidden scent-diffuser spread an odor while the problem was presented. In the sleep-with-conditioned-odor condition, task reactivation during sleep was induced by means of the odor that was also presented while participants were informed about the problem. In the sleep-with-control-odor condition, participants were exposed to a different odor during sleep than the one diffused during problem presentation. In the no odor condition, no odor was presented.

After a night of sleep with the conditioned odor, participants were found to be: (i) more creative; and (ii) better able to select their most creative idea than participants who had been exposed to a control odor or no odor while sleeping.

These findings suggest that we do not have to passively wait until we are hit by our creative muse while sleeping. Task reactivation during sleep can actively trigger creativity-related processes during sleep and thereby boost the beneficial effect of sleep on creativity.

{ Journal of Sleep Research/Wiley }

ideas, sleep | April 23rd, 2012 3:56 pm

Waking up from surgery can be disorienting. One minute you’re in an operating room counting backwards from 10, the next you’re in the recovery ward sans appendix, tonsils, or wisdom teeth. And unlike getting up from a good night’s sleep, where you know that you’ve been out for hours, waking from anesthesia feels like hardly any time has passed. Now, thanks to the humble honeybee, scientists are starting to understand this sense of time loss. New research shows that general anesthetics disrupt the social insect’s circadian rhythm, or internal clock, delaying the onset of timed behaviors such as foraging and mucking up their sense of direction. (…)

Warman says his team is currently looking at whether shining bright light at someone under anesthesia—a well known way to alter the circadian clock—could also reduce the procedure’s disorienting effects.

{ Science | Continue reading }

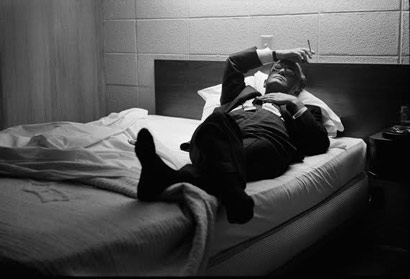

photo { Steve Shapiro, Truman Capote, Kansas, 1967 }

science, sleep, time | April 17th, 2012 10:27 am