‘War is a matter not so much of arms as of money.’ —Thucydides

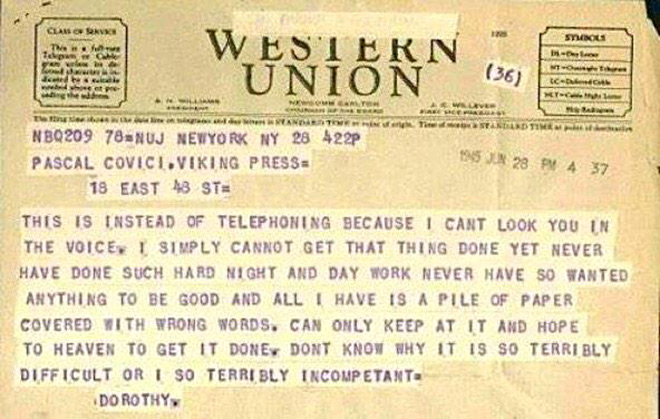

On January 2, 1977, the Shah of Iran made a painful admission about his country’s economy. “We’re broke,” he confided bluntly to his closest aide, court minister Asadollah Alam, in a private meeting. Alam predicted still more dangers to come: “We have squandered every cent we had only to find ourselves checkmated by a single move from Saudi Arabia,” he later wrote in a letter to the shah. “[W]e are now in dire financial peril and must tighten our belts if we are to survive.”

The two men were reacting to recent turmoil in the oil markets. A few weeks prior, at an OPEC meeting in Doha, the Saudis had announced they would resist an Iran-led majority vote to increase petroleum prices by 15 percent. (The shah needed the boost to pay for billions in new spending commitments.) King Khalid bin Abdulaziz Al Saud argued that a price hike wasn’t justified when Western economies were still mired in a recession — but he was also eager to place economic constraints on Iran at a time when the shah was ordering nuclear power plants and projecting influence throughout the Middle East. So the Saudis “flooded the markets,” ramping up oil production from 8 million to 11.8 million barrels per day and slashing crude prices. Unable to compete, Iran was quickly driven from the market: The country’s oil production plunged 38 percent in a month. Billions of dollars in anticipated oil revenues vanished, and Iran was forced to abandon its five-year budget estimates.

A damaging ripple effect persisted: Over the summer of 1977, industrial manufacturing in Iran fell by 50 percent. Inflation ran between 30 and 40 percent. The government made deep cuts to domestic spending to balance the books, but austerity only made matters worse when thousands of young, unskilled men lost their jobs. Before long, economic distress had eroded middle-class support for the shah’s monarchy — which collapsed two years later in the Iranian Revolution.

[…]

In November 2006, Nawaf Obaid, a Saudi security consultant connected to Prince Turki al-Faisal, then Saudi Arabia’s ambassador to Washington, wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post noting that if “[i]f Saudi Arabia boosted production and cut the price of oil in half … it would be devastating to Iran … [and] limit Tehran’s ability to continue funneling hundreds of millions each year to Shiite militias in Iraq and elsewhere.” Two years later, at the height of the global financial crisis, the Saudis acted: They flooded the market, and within six months, oil prices had fallen from their record high of $147 per barrel to just $33. Thus, Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad began 2009, an election year, struggling with the sudden collapse in government oil revenues and forced to slash popular subsidies and social programs. The election’s contested outcome was accompanied by economic contraction and the worst political violence in Iran since the fall of the shah.

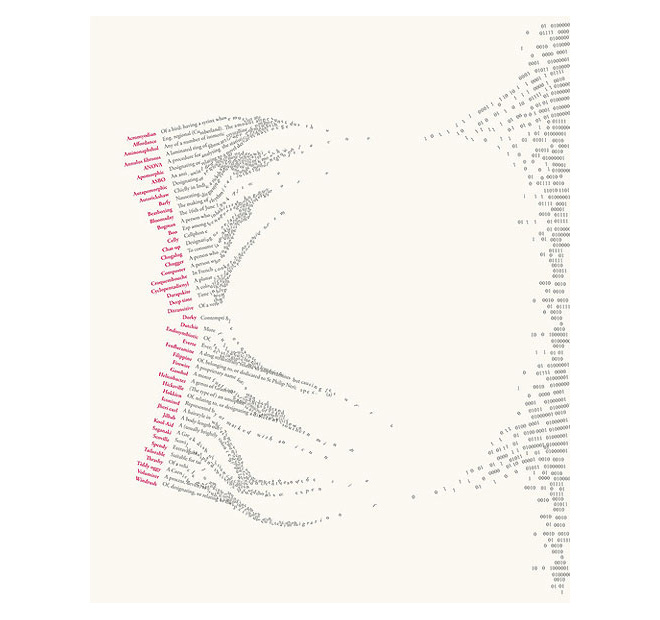

image { Evander Batson }

previously { The Conventional Wisdom On Oil Is Always Wrong }