showbiz

If a compact Riemannian manifold has positive Ricci curvature then its fundamental group is finite

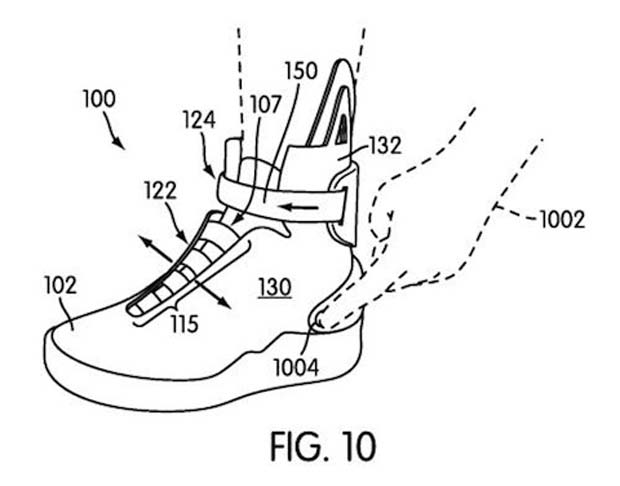

{ According to the World Intellectual Property Organization’s website and Dime, Tinker Hatfield and his boys at the Nike Innovative Kitchen have filed patent papers for a shoe with an automatic lacing system, such as seen on the Nike Air Mag from Back to the Future II. | Nice Kicks | more }

The game’s out there, and it’s play or get played. That simple.

Why We’re Teaching ‘The Wire’ at Harvard

“The Wire,” which depicted inner-city Baltimore over five seasons on HBO, shows ordinary people making sense of their world. Its complex characters on both sides of the law defy simplistic moral distinctions. (…) We think it is more than just excellent television. Impressed by its treatment of complex issues, we developed a course at Harvard drawing on the show’s portrayal of fundamental sociological principles connected to urban inequality. Our seminar was designed for 30 students; four times that many showed up for the first class last week.

Of course, our undergraduate students will read rigorous academic studies of the urban job market, education and the drug war. But the HBO series does what these texts can’t. More than simply telling a gripping story, “The Wire” shows how the deep inequality in inner-city America results from the web of lost jobs, bad schools, drugs, imprisonment, and how the situation feeds on itself.

Those kinds of connections are very difficult to illustrate in academic works. Though scholars know that deindustrialization, crime and prison, and the education system are deeply intertwined, they must often give focused attention to just one subject in relative isolation, at the expense of others. With the freedom of artistic expression, “The Wire” can be more creative. It can weave together the range of forces that shape the lives of the urban poor.

{ Julius Wilson and Anmol Chaddha/Harvard College | Continue reading }

photo { Anthony Suau }

We fell in love. I fell in love, she just stood there.

{ Woody Allen interview from 1971 after the release of Bananas | more }

You call that an argument? No, that’s a fact. The argument’s leaning over there against the door jamb.

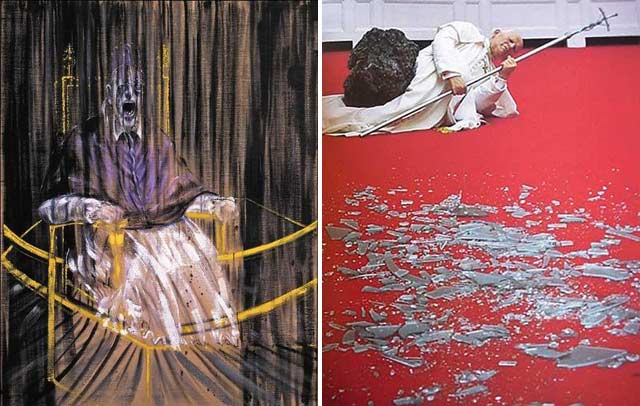

{ Pierre Huyghe, Third Memory, 1999 | Third Memory takes as its point of departure a bank robbery committed by John Woytowicz in Brooklyn in 1972; three years later the crime became the subject of Sidney Lumet’s film Dog Day Afternoon, starring Al Pacino. Huyghe tracked down Woytowicz and asked him to retell the story. Using a two-channel video projection, a television interview, and posters, Huyghe builds from a “first memory” of the original crime to a “second memory” with the film’s recreation of that crime, to arrive at a “third memory,” a rich blurring of the documented and the imagined. | San Francisco Museum of Modern Art | University of Virginia | Art Museum }

I can get Lady Fingers to come

Lancey Howard: Gets down to what it’s all about, doesn’t it? Making the wrong move at the right time.

Cincinnati Kid: Is that what it’s all about?

Lancey Howard: Like life, I guess.

But I know my luck too well, and I’ll probably never see you again

General “Buck” Turgidson: Mr. President, we are rapidly approaching a moment of truth both for ourselves as human beings and for the life of our nation. Now, truth is not always a pleasant thing. But it is necessary now to make a choice, to choose between two admittedly regrettable, but nevertheless *distinguishable*, postwar environments: one where you got twenty million people killed, and the other where you got a hundred and fifty million people killed.

President Merkin Muffley: You’re talking about mass murder, General, not war!

General “Buck” Turgidson: Mr. President, I’m not saying we wouldn’t get our hair mussed. But I do say no more than ten to twenty million killed, tops. Uh, depending on the breaks.

{ Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, 1964 | imdb | Continue reading }

But you do have a nervous system. And so does a computer.

While many of us watch 3-D entertainment in awe, others are compelled to look away. There just so happens to be a group of unlucky moviegoers who find that watching hyper 3-D images whiz by while sitting in the relatively still environment of a movie theater causes dizziness nausea, and other ill effects.

With funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF), experimental psychologists Frederick Bonato and Andrea Bubka of Saint Peter’s College in Jersey City, N.J., study this phenomenon, known as ‘cybersickness.’

“Cybersickness is a form of motion sickness that occurs in virtual reality environments,” says Bonato. “We have 3-D video games and 3-D movies, and now we have 3-D television. Viewing stimuli in 3-D may lead to some motion sickness symptoms to some degree.”

To understand cybersickness, you’ll need a quick lesson on motion sickness. “When we move around in the natural way, which is walking or running, the senses give you agreeing inputs,” says Bubka.

“But when your sense of motion doesn’t match up to your sense of sight, your brain may be reacting as if it’s been poisoned,” adds Bonato. “The reaction is to eliminate the poison by either vomiting or having diarrhea. It’s because of evolutionary hardwiring in the brain that leads the brain to mistakenly react as if poisoning has occurred.”

There is no real known reason why some people are more prone to motion sickness than others, the two researchers explain, but they do note some research has found that motion sickness seems to affect more women than men, and even people of certain ethnicities more than others.

“This isn’t just a human problem, either,” notes Bonato. “Motion sickness is experienced by most vertebrates. When some fish are transported in tanks in aircraft, they later find fish vomit, which indicates that the fish developed motion sickness on the ride.”

You can easily get past, but that chapter is done

{ Michael Kenneth Williams photographed by TR for Vice }

{ Marco Ovando photographed by Ari Levanael, T-shirt by Christopher Lee Sauvé }

Queer the number of pins they always have. No roses without thorns.

To those who know his name at all in America, Jean Eustache may be a one-hit wonder. But in France he’s far and away the most important filmmaker of the post–New Wave era. Eustache left an indelible mark on French cinema and exercised a profound influence on such directors as Olivier Assayas, Catherine Breillat, Claire Denis, Philippe Garrel, and Benoit Jacquot. His 1973 The Mother and the Whore is the kind of movie that few filmmakers even allow themselves to conindex, let alone make: brutally honest as self-portraiture, as frank about human relationships (sexual and otherwise) as movies have ever gotten, and the last word on post-’68 bohemian Paris. Eustache died before his time (by his own hand) in 1981. Often likened to John Cassavetes, he stands alone as a unique and visionary practitioner of the art.

Une sale histoire (A Dirty Story), directed by Jean Eustache, 1977

In A Dirty Story Jean Eustache presents the same story of storytelling twice: once in documentary fashion, filmed his friend Jean-Noël Picq in 16mm black and white, and a second time in 35mm color with the actor Michael Lonsdale reciting the same lines. Eustache invited his Jean-Noël Picq to sit down with a group of people to recount in detail how once, in the men’s room of a Parisian restaurant, he found a hole in the wall and peered through to a perfect view of the ladies’ room. In order to test his contention that the actor would prove more convincing than the real-life storyteller, Eustache placed the fictional version first. While the film never shows anything more shocking than a man talking, French censors gave the film an X rating, proving Eustache’s claim that “sex has nothing to do with morals, not even with aesthetics; sex is a metaphysical affair.”

Full second part (unsubtitled):

There is six different wings in the spot, choose one

Founded in 1974 and based in Los Angeles, the Z Channel was the nation’s first pay-cable station, preceding HBO or Showtime. At its pinnacle in the early 1980s, it served only 100,000 viewers, but nonetheless inspired and influenced the movie industry with its eclectic fare, securing a unique place in film history.

{ Netflix }

The Z Channel was known for its devotion to the art of cinema due to the eclectic choice of films by the programming chief, Jerry Harvey. It also popularized the use of letterboxing on television, as well as showing ‘director’s cut’ versions of films (which is a term popularized after Z Channel’s showing of Heaven’s Gate). Z Channel’s devotion to cinema and choice of rare and important films had an important influence on such directors as Robert Altman, Quentin Tarantino, and Jim Jarmusch. In 1989, Z Channel faded to black and was replaced by SportsChannel Los Angeles.

photo { Otto Obrien }

‘First of all, I would like to make one thing quite clear. I never explain anything.’ –Mary Poppins

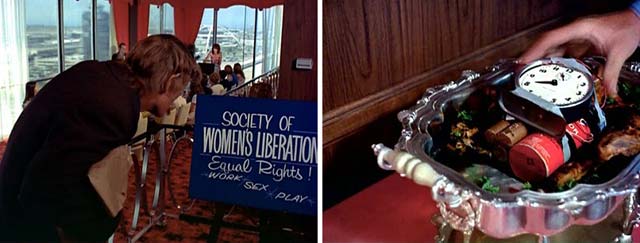

In 1968, The MPAA created the Classification and Ratings Administration (CARA) to designate films with one of four ratings: G (general audiences), M (mature audiences), R (children under sixteen years old not admitted without parent or guardian), and X (children under seventeen years old not admitted). Three years later M became PG (parental guidance suggested). In 1984, in response to violence in the movie Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, the film review board instituted the new PG-13 rating, which cautions parents that the film’s contents may be inappropriate for children under age thirteen. In 1990 the board responded to criticism that the X rating unfairly categorized artistic adult films, such as Midnight Cowboy, with hard-core pornography. In that year the board replaced X with NC-17.

In the movie business, a better rating is generally a lower rating. Movies typically make more money when they appeal to the widest possible audience. This rule holds true particularly with motion picture video sales. Many video outlets limit their inventory to movies with ratings no higher than PG-13 or R. Some theaters refuse to show movies with the NC-17 rating, and some newspapers refuse to carry advertisements for movies with the NC-17 rating. A movie studio therefore wants its film to earn the least restrictive rating possible.

One exception to this general rule is the marketing of pornographic films. Because studies have suggested that sexually explicit films become more desirable when they are restricted, the pornographic film industry voluntarily labels its films X or XXX in an effort to increase sales. XXX is a marketing tool, not an actual MPAA rating.

It’s incredibly obvious, isn’t it? A foreign substance is introduced into our precious bodily fluids without the knowledge of the individual.

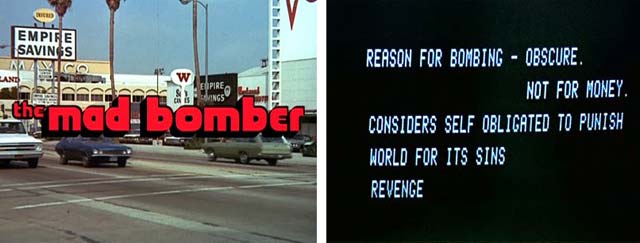

Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)’s frightening absurdity was established in the very first frame of the main title sequence designed by Pablo Ferro. (…)

Surprinted on these frames the film’s title and credits are full-screen graffiti-like scrawls comprised of thick and thin hand-drawn letters, unlike any movie title that had preceded it. (…)

It launched the long career of Pablo Ferro as title designer, trailer director, and feature filmmaker. Yet before he started designing film titles the Cuban born Ferro (b 1935), who had emigrated to New York City when he was twelve years old - and quickly became a huge film fan and aficionado of UPA cartoons - had earned a reputation for directing and editing scores of television commercials. After graduating from Manhattan’s High School of Industrial Art, Ferro began working at Atlas Comics in 1951 as an inker and artist in the EC-horror tradition. (…)

As a consummate experimenter, Ferro introduced the kinetic quick-cut method of editing whereby static images (including engravings, photographs, and pen and ink drawings) were infused with speed, motion, and sound. In the late 1950s most live-action commercials were shot with one or two stationary cameras, conversely Ferro took full advantage of stop-motion technology, as well shooting his own jerky footage with a handheld Bolex. Unlike most TV commercial directors, Ferro maintained a strong appreciation and understanding for typography such that in the late 1950s he pioneered the use of moving type on the TV screen. (…)

Ferro’s title for The Thomas Crown Affair, directed by Norman Jewison in 1968, introduced multi-screen effects for the first time in any feature motion picture and defined a cinematic style of the late 1960s. (…)

The Thomas Crown Affair won an Academy Award and served as a model for other films of that era (remember Woodstock?). It also convinced Steve McQueen, who starred in and produced the film, to hire Ferro to do titles for his next movie, Bullitt, which launched an uninterrupted thirty-year string of title and trailer commissions. (…)

One of his most engaging recent title sequences, edited with his son Allen Ferro, for the 1995 murder farce To Die For, directed by Gus Van Sant, gave him an opportunity to test how far he could develop the film’s leading character in the few minutes prior to the start of the action.

screenshots { Dr. Strangelove }

bonus:

There are only three people in LA. Everything else is done with mirrors.

In the fall of 1996, a $30-million Hollywood production almost ground to a halt because of facial hair. As producer Art Linson recounted in his 2002 memoir, “What Just Happened?,” Alec Baldwin surprised everyone when he showed up to film “The Edge” (1997), a man-against-nature thriller, with an overgrown beard. A profanity-laced debate ensued between producer, star, agent and studio executives.

Finally it came down to this: The execs, who had already sunk millions into the production, wouldn’t shoot the picture with their expensive star acting behind a hairy hedge. The stand-off might have ended badly for the studio if the star had walked, but in the end he didn’t: Mr. Baldwin blinked, emerging from his trailer clean-shaven for the first day of filming.

Why risk so much money over a few whiskers? The answer to that question and other mysteries of modern-day film financing can be found in “The Hollywood Economist,” Edward Jay Epstein’s latest foray into the seamy underbelly of Hollywood spreadsheets.