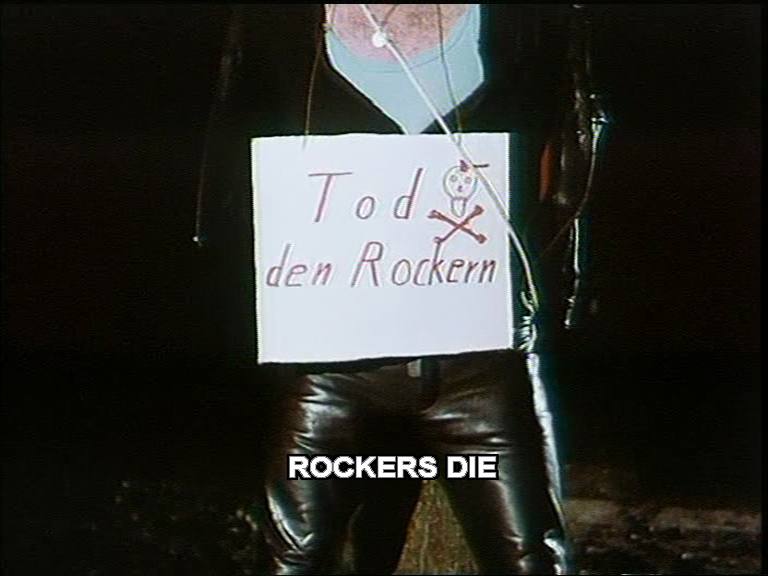

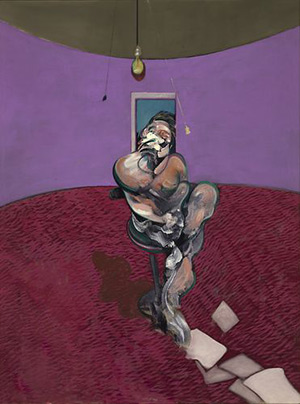

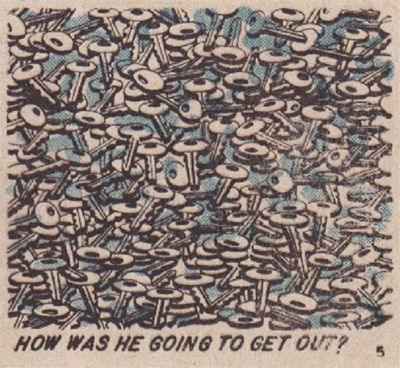

Cooping was an alleged form of electoral fraud in the United States cited in relation to the death of Edgar Allan Poe in October 1849, by which unwilling participants were forced to vote, often several times over, for a particular candidate in an election. According to several of Poe’s biographers, these innocent bystanders would be grabbed off the street by so-called ‘cooping gangs’ or ‘election gangs’ working on the payroll of a political candidate, and they would be kept in a room, called the “coop”, and given alcoholic beverages in order for them to comply. If they refused to cooperate, they would be beaten or even killed. Often their clothing would be changed to allow them to vote multiple times. Sometimes the victims would be forced to wear disguises such as wigs, fake beards or mustaches to prevent them from being recognized by voting officials at polling stations.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

On October 3, 1849, Edgar Allan Poe was found delirious on the streets of Baltimore, “in great distress, and… in need of immediate assistance”, according to Joseph W. Walker who found him. He was taken to the Washington Medical College where he died on Sunday, October 7, 1849 at 5:00 in the morning. He was not coherent long enough to explain how he came to be in his dire condition and, oddly, was wearing clothes that were not his own.

He is said to have repeatedly called out the name “Reynolds” on the night before his death, though it is unclear to whom he was referring.

All medical records and documents, including Poe’s death certificate, have been lost, if they ever existed.

Newspapers at the time reported Poe’s death as “congestion of the brain” or “cerebral inflammation”, common euphemisms for death from disreputable causes such as alcoholism.

The actual cause of death remains a mystery. […] One theory dating from 1872 suggests that cooping was the cause of Poe’s death, a form of electoral fraud in which citizens were forced to vote for a particular candidate, sometimes leading to violence and even murder. […] Cooping had become the standard explanation for Poe’s death in most of his biographies for several decades, though his status in Baltimore may have made him too recognizable for this scam to have worked. […]

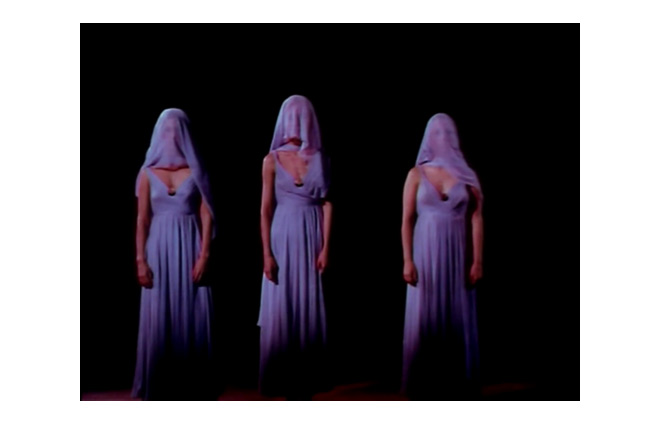

Immediately after Poe’s death, his literary rival Rufus Wilmot Griswold wrote a slanted high-profile obituary under a pseudonym, filled with falsehoods that cast him as a lunatic and a madman, and which described him as a person who “walked the streets, in madness or melancholy, with lips moving in indistinct curses, or with eyes upturned in passionate prayers, (never for himself, for he felt, or professed to feel, that he was already damned)”.

The long obituary appeared in the New York Tribune signed “Ludwig” on the day that Poe was buried. It was soon further published throughout the country. The piece began, “Edgar Allan Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it.” “Ludwig” was soon identified as Griswold, an editor, critic, and anthologist who had borne a grudge against Poe since 1842. Griswold somehow became Poe’s literary executor and attempted to destroy his enemy’s reputation after his death.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }