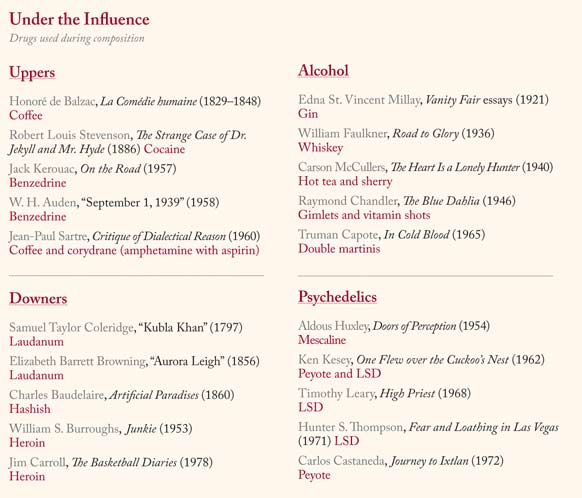

It will only be parlayed into a memory

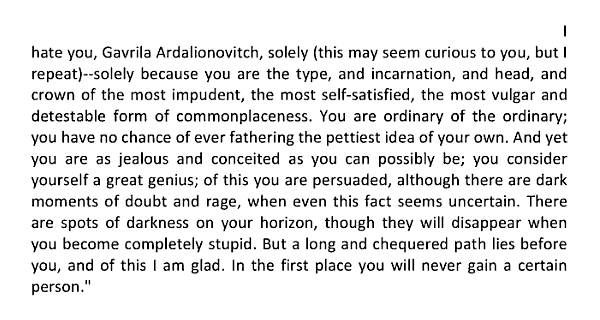

Dr. Raymond Mar, of On Fiction: An Online Magazine on the Psychology of Fiction, published a research bulletin the other day summarizing a psychological study whose results apparently suggest that, in the words of the blog headline, “words reveal the personality of the writers.” After presenting the background, experimental procedure, and findings, Dr. Mar concludes that “From these findings, it appears that creative writing can indeed reveal aspects of the author’s personality to readers. An encouraging result for those of us who feel we’ve come to know an author by reading his or her books.”

I was excited by the headline. Typically, I approach reading as entering into a relationship with a writer and, when it comes to reading the works of cherished writers, I often work with the fantasy that I’m getting to them better, more intimately. I even once had the experience of hallucinating an encounter with a dead author while visiting with his widow in their apartment in Paris. But as I read through Dr. Mar’s report of the study I was left with some questions and even some objections.

First, the background to the study. According to Dr. Mar:

A fascinating study currently In Press in the Journal of Research in Personality (Kufner et al., in press), provides evidence that in some ways, we can infer what an author is like based solely on their writing. Although previous studies on inferring personality from written text have been conducted, this was the first study to look at creative writing as opposed to personal essays.

{ Yago Colás/ScientificBlogging | Continue reading | Thanks Emma }

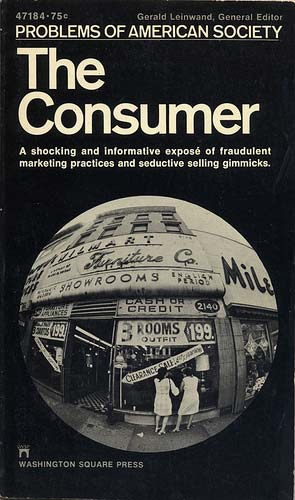

For 40 years, Barnes & Noble has dominated bookstore retailing. In the 1970s it revolutionized publishing by championing discount hardcover best sellers. In the 1990s, it helped pioneer book superstores with selections so vast that they put many independent bookstores out of business.

Today it boasts 1,362 stores, including 719 superstores with 18.8 million square feet of retail space—the equivalent of 13 Yankee Stadiums.

But the digital revolution sweeping the media world is rewriting the rules of the book industry, upending the established players which have dominated for decades. Electronic books are still in their infancy, comprising an estimated 3% to 5% of the market today. But they are fast accelerating the decline of physical books, forcing retailers, publishers, authors and agents to reinvent their business models or be painfully crippled.

“By the end of 2012, digital books will be 20% to 25% of unit sales, and that’s on the conservative side,” predicts Mike Shatzkin, chief executive of the Idea Logical Co., publishing consultants. “Add in another 25% of units sold online, and roughly half of all unit sales will be on the Internet.”

Nowhere is the e-book tidal wave hitting harder than at bricks-and-mortar book retailers. The competitive advantage Barnes & Noble spent decades amassing—offering an enormous selection of more than 150,000 books under one roof—was already under pressure from online booksellers.

It evaporated with the recent advent of e-bookstores, where readers can access millions of titles for e-reader devices.

related { Book sales, frumpy readers, and mental rotation of book titles }

illustration { vb infinite swell in infinite indumentum | Imp Kerr & Associates, NYC }