I once said this to Michel Foucault, who was more hostile to Derrida even than I am, and Foucault said that Derrida practiced the method of obscurantisme terroriste (terrorism of obscurantism). We were speaking French. And I said, “What the hell do you mean by that?” And he said, “He writes so obscurely you can’t tell what he’s saying, that’s the obscurantism part, and then when you criticize him, he can always say, ‘You didn’t understand me; you’re an idiot.’ That’s the terrorism part.”

{ John Searle | via Open Culture | Continue reading }

michel foucault | July 15th, 2013 2:34 pm

A second problem is that Foucault’s concept of resistance lacks a notion of emancipation. As the autonomist Marxist John Holloway argues, “in Foucault’s analysis, there are a whole host of resistances which are integral to power, but there is no possibility of emancipation. The only possibility is an endlessly shifting constellation of power and resistance.”

{ Logos | Continue reading }

michel foucault | April 11th, 2013 1:21 pm

Turning to Foucault, of course we see that power is not simply the ability to dominate. Rather, power

is a set of actions on possible actions; it incites, it induces, it seduces, it makes easier or more difficult; it releases or contrives, makes more probable or less; in the extreme, it constrains or forbids absolutely, but it is always a way of acting upon one or more acting subjects by virtue of their acting or being capable of action. A set of actions upon other actions.

In other words, anyone subject to power is free to act, is an acting subject, but the power relationship either subtly or explicitly contains the subject’s possible courses of action. There is freedom in power, because freedom operates within power.

{ First Monday | Continue reading | Thanks Rob | Michel Foucault, The Subject and Power, 1982 }

michel foucault | March 14th, 2013 1:03 pm

The theory that Foucault lays out in his Discipline and Punish which provides a philosophical history of the modern prison is essentially this: The prison emerged in the late 18th and 19th centuries not as a humanitarian project of Enlightenment philosophes, but as a disciplinary apparatus of society in conjunction with other disciplinary institutions- the insane asylum, the workhouse, the factory, the reformatory, the school, and branches of knowledge- psychology, criminology, that had as their end what might be called the domestication of human beings. It might be hard for us to believe but the prison is a very modern institution — not much older than the 19th century. The idea that you should detain people convicted of a crime for long periods perhaps with the hope of “rehabilitating” them just hadn’t crossed anyone’s mind before then. Instead, punishment was almost immediate, whether execution, physical punishment or fines. With the birth of the prison, gone was the emotive wildness of the prior era- the criminal wracked by sin and tortured for his transgression against his divine creator and human sovereign. In its place rose up the patient, “humane” transformation of the “abnormal,” “deviant” individual into a law and norm abiding member of society.

{ IEET | Continue reading }

michel foucault | February 2nd, 2013 6:18 am

Cognition researchers should beware assuming that people’s mental faculties have finished maturing when they reach adulthood. So say Laura Germine and colleagues, whose new study shows that face learning ability continues to improve until people reach their early thirties.

Although vocabulary and other forms of acquired knowledge grow throughout the life course, it’s generally accepted that the speed and efficiency of the cognitive faculties peaks in the early twenties before starting a steady decline. This study challenges that assumption.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

painting { Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas (Spanish for “The Maids of Honour”), 1656 | Las Meninas has long been recognised as one of the most important paintings in Western art history. Foucault viewed the painting without regard to the subject matter, nor to the artist’s biography, technical ability, sources and influences, social context, or relationship with his patrons. Instead he analyses its conscious artifice, highlighting the complex network of visual relationships between painter, subject-model, and viewer. For Foucault, Las Meninas contains the first signs of a new episteme, or way of thinking, in European art. It represents a mid-point between what he sees as the two “great discontinuities” in art history. | Wikipedia }

art, ideas, michel foucault, psychology, science | February 15th, 2011 9:20 pm

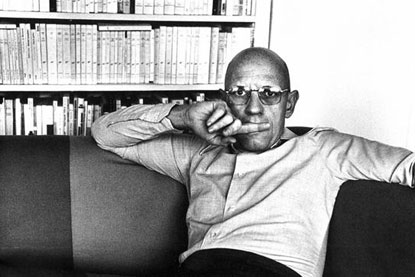

I like discussions, and when I am asked questions, I try to answer them. [But] I don’t like to get involved in polemics. If I open a book and see that the author is accusing an adversary of “infantile leftism” I shut it right away. That’s not my way of doing things. (…) A whole morality is at stake, the one that concerns the search for truth and the relation to the other. (…)

The polemicist proceeds encased in privileges that he possesses in advance and will never agree to question. On principle, he possesses rights authorizing him to wage war and making that struggle a just undertaking; the person he confronts is not a partner in search for the truth but an adversary, an enemy who is wrong, who is armful, and whose very existence constitutes a threat. For him, then the game consists not of recognizing this person as a subject having the right to speak but of abolishing him as interlocutor, from any possible dialogue; and his final objective will be not to come as close as possible to a difficult truth but to bring about the triumph of the just cause he has been manifestly upholding from the beginning. The polemicist relies on a legitimacy that his adversary is by definition denied.

{ Michel Foucault, interview conducted by Paul Rabinow, May 1984 | Continue reading }

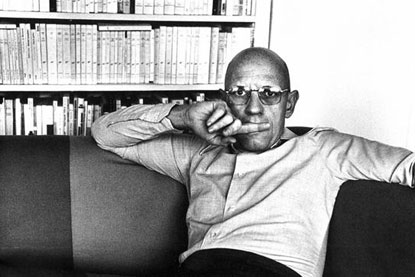

photo { Tony Stamolis }

michel foucault | December 9th, 2010 8:00 pm

michel foucault | June 26th, 2010 11:03 am

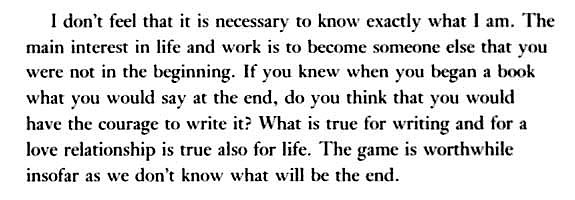

before writing a book, michel foucault used to write a draft, 500 or 600 pages of notes and first thoughts. only when he was done w/ this first draft, did he start the actual book, meaning going to the libraries doing research and digging into the archives, spending months or years probing his subject. he was satisfied only when the final book was the opposite of the initial draft, when the final text was contradicting, almost point by point, the 500-page draft. only then he knew his book was finished, when he wasn’t that guy who wrote the draft anymore. after he rewrote himself like he rewrote his draft.

or john maynard keynes: when the facts change, i change my mind. what do you do, sir?

{ Imp Kerr & Associates, NYC }

experience, michel foucault | June 16th, 2010 12:33 pm

In the social sciences (following the work of Michel Foucault), a discourse is considered to be a formalized way of thinking that can be manifested through language, a social boundary defining what can be said about a specific topic, or, as Judith Butler puts it, “the limits of acceptable speech”—or possible truth.

Discourses are seen to affect our views on all things; it is not possible to escape discourse. For example, two notably distinct discourses can be used about various guerrilla movements describing them either as “freedom fighters” or “terrorists.” In other words, the chosen discourse delivers the vocabulary, expressions and perhaps also the style needed to communicate. Discourse is closely linked to different theories of power and state, at least as long as defining discourses is seen to mean defining reality itself. It also helped some of the world’s greatest thinkers express their thoughts and ideas into what is now called “public orality.”

This conception of discourse is largely derived from the work of French philosopher Michel Foucault (see below).

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

photo { Richard Kalvar }

Linguistics, ideas, michel foucault | June 1st, 2010 9:12 pm