The Voynich Manuscript has been dubbed “The Most Mysterious Manuscript in the World.” It is named after its discoverer, the American antique book dealer and collector, Wilfrid M. Voynich, who discovered it in 1912, amongst a collection of ancient manuscripts kept in villa Mondragone in Frascati, near Rome.

No one knows the origins of the manuscript. Experts believe it was written in between the 15th and 17th centuries. The manuscript is small, seven by ten inches, but thick, nearly 235 pages.

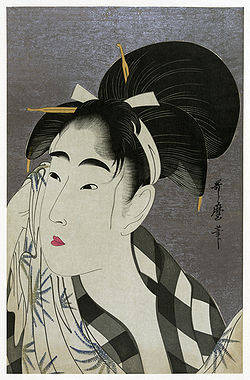

Its pages are filled with hand-written text and crudely drawn illustrations. The illustrations depict plants, astrological diagrams, and naked women. The women could represent creation and rebirth of consciousness.

These illustrations are strange, but much stranger is the text itself, because the manuscript is written entirely in a mysterious, unknown alphabet that has defied all attempts at translation.

It is an alphabetic script, but of an alphabet variously reckoned to have from nineteen to twenty-eight letters, none of which bear any relationship to any English or European letter system. The text has no apparent corrections. There is evidence for two different “languages” (investigated by Currier and D’Imperio) and more than one scribe, probably indicating an ambiguous coding scheme.

Apparently, Voynich wanted to have the mysterious manuscript deciphered and provided photographic copies to a number of experts. However, despite the efforts of many well known cryptologists and scholars, the book remains unread. There are some claims of decipherment, but to date, none of these can be substantiated with a complete translation. (…)

The Voynich Manuscript first appears in 1586 at the court of Rudolph II of Bohemia, who was one of the most eccentric European monarchs of that or any other period. Rudolph collected dwarfs and had a regiment of giants in his army. He was surrounded by astrologers, and he was fascinated by games and codes and music. He was typical of the occult-oriented, Protestant noblemen of this period and epitomized the liberated northern European prince. He was a patron of alchemy and supported the printing of alchemical literature. (…)

Over its recorded existence, the Voynich manuscript has been the object of intense study by many professional and amateur cryptographers, including some top American and British codebreakers of World War II fame (all of whom failed to decipher a single word). This string of failures has turned the Voynich manuscript into a famous subject of historical cryptology, but it has also given weight to the theory that the book is simply an elaborate hoax - a meaningless sequence of arbitrary symbols. (…)

By current estimates, the book originally had 272 pages in 17 quires of 16 pages each. Only about 240 vellum pages remain today, and gaps in the page numbering (which seems to be later than the text) indicate that several pages were already missing by the time that Voynich acquired it. A quill pen was used for the text and figure outlines, and colored paint was applied (somewhat crudely) to the figures, possibly at a later date.

The illustrations of the manuscript shed little light on its contents, but imply that the book consists of six “sections”, with different styles and subject matter. Except for the last section, which contains only text, almost every page contains at least one illustration. The sections, and their conventional names, are: The “herbal” section, Astronomical, Cosmological, Pharmaceutical. (…)

The text was clearly written from left to right, with a slightly ragged right margin. Longer sections are broken into paragraphs, sometimes with “bullets” on the left margin. There is no obvious punctuation. The ductus (the speed, care, and cursiveness with which the letters are written) flows smoothly, as if the scribe understood what he was writing when it was written; the manuscript does not give the impression that each character had to be calculated before being put on the page.

The text consists of over 170,000 discrete glyphs, usually separated from each other by thin gaps. Most of the glyphs are written with one or two simple pen strokes. While there is some dispute as to whether certain glyphs are distinct or not, an alphabet with 20-30 glyphs would account for virtually all of the text; the exceptions are a few dozen “weird” characters that occur only once or twice each.

Wider gaps divide the text into about 35,000 “words” of varying length. These seem to follow phonetic or orthographic laws of some sort; e.g. certain characters must appear in each word (like the vowels in English), some characters never follow others, some may be doubled but others may not.

Statistical analysis of the text reveals patterns similar to natural languages. For instance, the word frequencies follow Zipf’s law, and the word entropy (about 10 bits per word) is similar to that of English or Latin texts. Some words occur only in certain sections, or in only a few pages; others occur throughout the manuscript. There are very few repetitions among the thousand or so “labels” attached to the illustrations. In the herbal section, the first word on each page occurs only on that page, and may be the name of the plant.

On the other hand, the Voynich manuscript’s “language” is quite unlike European languages in several aspects. For example, there are practically no words with more than ten “letters”, yet there are also few one or two-letter words.

The distribution of letters within the word is also rather peculiar: some characters only occur at the beginning of a word, some only at the end, and some always in the middle section.

The text seems to be more repetitious than typical European languages; there are instances where the same common word appears up to three times in a row. Words that differ only by one letter also repeat with unusual frequency.

There are only a few words in the manuscript written in a seemingly Latin script. In the last page there are four lines of writing which are written in (rather distorted) Latin letters, except for two words in the main script. The lettering resembles European alphabets of the 15th century, but the words do not seem to make sense in any language.

Also, a series of diagrams in the “astronomical” section has the names of ten of the months (from March to December) written in Latin script, with spelling suggestive of the medieval languages of France or the Iberian Peninsula. However, it is not known whether these bits of Latin script were part of the original text, or were added at a later time. (…)

Dr. Leonell Strong, a cancer research scientist and amateur cryptographer, tried to decipher the Voynich manuscript. Strong said that the solution to the Voynich manuscript was a “peculiar double system of arithmetical progressions of a multiple alphabet”. Strong claimed that the plaintext revealed the Voynich manuscript to be written by the 16th century English author Anthony Ascham, whose works include A Little Herbal, published in 1550. Although the Voynich manuscript does contain sections resembling an herbal, the main argument against this theory is that it is unknown where Anthony would have obtained such literary and cryptographic knowledge. (…)

The first section of the book is almost certainly an herbal, but attempts to identify the plants, either with actual specimens or with the stylized drawings of contemporary herbals, have largely failed. Only a couple of plants (including a wild pansy and the maidenhair fern) can be identified with some certainty. Those “herbal” pictures that match “pharmacological” sketches appear to be “clean copies” of these, except that missing parts were completed with improbable-looking details. In fact, many of the plants seem to be composite: the roots of one species have been fastened to the leaves of another, with flowers from a third.

{ Ellie Crystal | Continue reading | Images | Wikipedia }

Its language is unknown and unreadable, though some believe it bears a message from extraterrestrials. Others say it carries knowledge of a civilisation that is thousands of years old.

But now a British academic believes he has uncovered the secret of the Voynich manuscript, an Elizabethan volume of more than 200 pages that is filled with weird figures, symbols and writing that has defied the efforts of the twentieth century’s best codebreakers and most distinguished medieval scholars.

According to computer expert Gordon Rugg of Keele University, the manuscript represents one of the strangest acts of encryption ever undertaken, one that made its creator, Edward Kelley, an Elizabethan entrepreneur, a fortune before his handiwork was lost to the world for more than 300 years. (…)

But now the computer expert and his team believe they have found the secret of the Voynich manuscript.

They have shown that its various word, which appear regularly throughout the script, could have been created using table and grille techniques. The different syllables that make up words are written in columns, and a grille - a piece of cardboard with three squares cut out in a diagonal pattern - is slid along the columns.

The three syllables exposed form a word. The grille is pushed along to expose three new syllables, and a new word is exposed.

Rugg’s conclusion is that Voynichese - the language of the Voynich manuscript - is utter gibberish, put together as random assemblies of different syllables.

{ The Guardian | Wired }