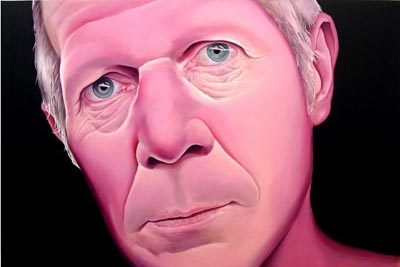

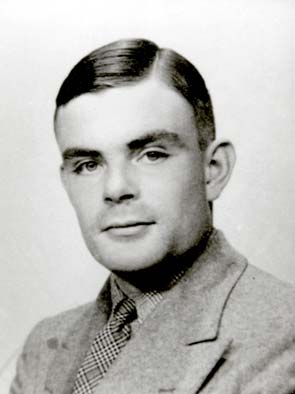

Alan Turing (1912 – 1954) was an English mathematician, logician, cryptanalyst, and computer scientist, who also wrote papers over a whole spectrum of subjects, from philosophy and psychology through to physics, chemistry and biology. He was influential in the development of computer science and providing a formalisation of the concept of the algorithm and computation with the Turing machine (1934-1936).

In 1999, Time Magazine named Turing as one of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century for his role in the creation of the modern computer, and stated: “The fact remains that everyone who taps at a keyboard, opening a spreadsheet or a word-processing program, is working on an incarnation of a Turing machine.”

During the Second World War, Turing was recruited to serve in the Government Code and Cypher School, located in a Victorian mansion called Bletchley Park. The task of all those so assembled — mathematicians, chess champions, Egyptologists, whoever might have something to contribute about the possible permutations of formal systems — was to break the Enigma codes used by the Nazis in communications between headquarters and troops.

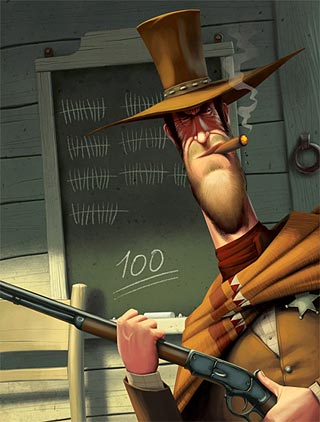

Because of secrecy restrictions, Turing’s role in this enterprise was not acknowledged until long after his death. And like the invention of the computer, the work done by the Bletchley Park crew was very much a team effort. But it is now known that Turing played a crucial role in designing a primitive, computer-like machine that could decipher at high speed Nazi codes to U-boats in the North Atlantic.

In 1948, Turing, working with his former undergraduate colleague, D. G. Champernowne, began writing a chess program for a computer that did not yet exist. In 1952, lacking a computer powerful enough to execute the program, Turing played a game in which he simulated the computer, taking about half an hour per move. The game was recorded.

In 1950, his Turing test was a significant and characteristically provocative contribution to the debate regarding artificial intelligence.

After 1952, Turing became interested in chemistry and worked on mathematical biology. He wrote a paper on the chemical basis of morphogenesis, and predicted oscillating chemical reactions, which were first observed in the 1960s.

Turing’s homosexuality resulted in a criminal prosecution in 1952.

In January 1952 Turing picked up 19-year-old Arnold Murray outside a cinema in Manchester. After Murray helped an accomplice to break into his house, Turing reported the crime to the police. During the investigation, Turing acknowledged a sexual relationship with Murray. Homosexual acts were illegal in the United Kingdom at that time, and so both were charged with gross indecency under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, the same crime that Oscar Wilde had been convicted of more than fifty years earlier.

Turing was given a choice between imprisonment or probation conditional on his agreement to undergo hormonal treatment designed to reduce libido. He accepted chemical castration via female hormone injections, one of the side effects of which was that he grew breasts.

On 8 June 1954, Turing’s cleaner found him dead; he had died the previous day. A post-mortem examination established that the cause of death was cyanide poisoning. When his body was discovered an apple lay half-eaten beside his bed, and although the apple was not tested for cyanide, it is speculated that this was the means by which a fatal dose was delivered. An inquest determined that he had committed suicide.

On 10 September 2009, following an Internet campaign, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown made an official public apology on behalf of the British government for the way in which Turing was treated after the war.

{ Wikipedia | Time }