art

In his groundbreaking research, Geoffrey Miller (1999) suggests that artistic and creative displays are male-predominant behaviors and can be considered to be the result of an evolutionary advantage. The outcomes of several surveys conducted on jazz and rock musicians, contemporary painters, English writers (Miller, 1999), and scientists (Kanazawa, 2000) seem to be consistent with the Millerian hypothesis, showing a predominance of men carrying out these activities, with an output peak corresponding to the most fertile male period and a progressive decline in late maturity.

One way to evaluate the sex-related hypothesis of artistic and cultural displays, considered as sexual indicators of male fitness, is to focus on sexually dimorphic traits. One of them, within our species, is the 2nd to 4th digit length (2D:4D), which is a marker for prenatal testosterone levels.

This study combines the Millerian theories on sexual dimorphism in cultural displays with the digit ratio, using it as an indicator of androgen exposure in utero. If androgenic levels are positively correlated with artistic exhibition, both female and male artists should show low 2D:4D ratios. In this experiment we tested the association between 2D:4D and artistic ability by comparing the digit ratios of 50 artists (25 men and 25 women) to the digit ratios of 50 non-artists (25 men and 25 women).

Both male and female artists had significantly lower 2D:4D ratios (indicating high testosterone) than male and female controls. These results support the hypothesis that art may represent a sexually selected, typically masculine behavior that advertises the carrier’s good genes within a courtship context.

{ Evolutionary Psychology | PDF }

previously { Contrary to decades of archaeological dogma, many of the first artists were women }

art, hormones, psychology | June 4th, 2014 2:07 pm

art | May 9th, 2014 1:44 pm

Cutting, a professor at Cornell University, wondered if a psychological mechanism known as the “mere-exposure effect” played a role in deciding which paintings rise to the top of the cultural league.

In a seminal 1968 experiment, people were shown a series of abstract shapes in rapid succession. Some shapes were repeated, but because they came and went so fast, the subjects didn’t notice. When asked which of these random shapes they found most pleasing, they chose ones that, unbeknown to them, had come around more than once. Even unconscious familiarity bred affection.

Back at Cornell, Cutting designed an experiment to test his hunch. Over a lecture course he regularly showed undergraduates works of impressionism for two seconds at a time. Some of the paintings were canonical, included in art-history books. Others were lesser known but of comparable quality. These were exposed four times as often. Afterwards, the students preferred them to the canonical works, while a control group of students liked the canonical ones best. Cutting’s students had grown to like those paintings more simply because they had seen them more.

Cutting believes his experiment offers a clue as to how canons are formed. He points out that the most reproduced works of impressionism today tend to have been bought by five or six wealthy and influential collectors in the late 19th century. The preferences of these men bestowed prestige on certain works, which made the works more likely to be hung in galleries and printed in anthologies. The kudos cascaded down the years, gaining momentum from mere exposure as it did so. The more people were exposed to, say, “Bal du Moulin de la Galette”, the more they liked it, and the more they liked it, the more it appeared in books, on posters and in big exhibitions. Meanwhile, academics and critics created sophisticated justifications for its pre-eminence. […]

The process described by Cutting evokes a principle that the sociologist Duncan Watts calls “cumulative advantage”: once a thing becomes popular, it will tend to become more popular still.

{ Intelligent Life | Continue reading }

art { Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (crown of thorns), circa 1982 | Bill Connors }

art, psychology | May 7th, 2014 2:38 pm

{ One man’s nearly three-decade quest to authenticate a potential Mark Rothko painting purchased at auction for $319.50 plus tax has turned up convincing evidence in the work’s favor, but the experts seem unlikely to issue a ruling. Rothko expert David Anfam, who published the artist’s catalogue raisonné in 1998, has been familiar with Himmelfarb’s painting since the late 1980s. The scholar even discovered a black-and-white photograph of the work in the archives held by Rothko’s family, but still declined to include the work in his book. | Artnet | full story }

economics, rothko | April 25th, 2014 2:43 pm

In the last years news are over and over again about record breaking prices reached for an artwork at a public auction. Such high pricing strucks not only the old masters but also works for still living artists. As you might know the prices for young artist’s paintings are often assessed by canvas size. So the question for my use-case arises: Is there also a correlation between size and hammer price of famous artworks at auctions?

{ Ruth Reiche | Continue reading }

art, economics | March 14th, 2014 5:10 am

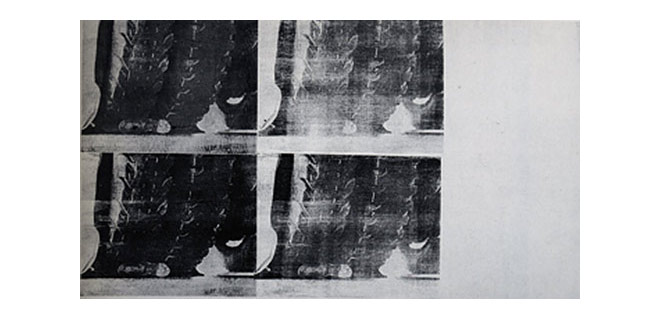

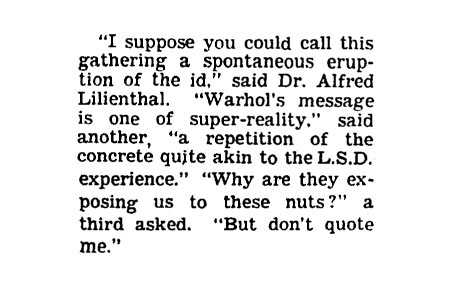

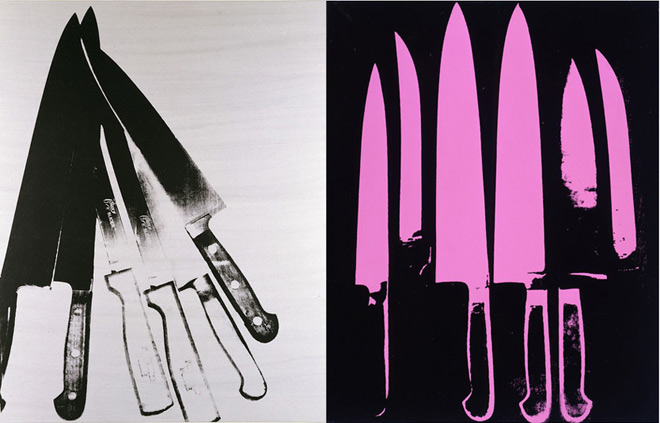

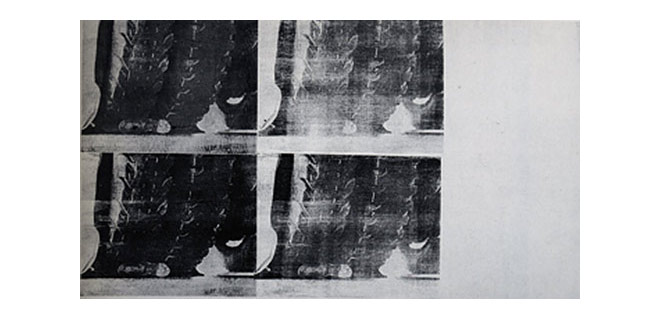

Le pop art dépersonnalise, mais il ne rend pas anonyme : rien de plus identifiable que Marilyn, la chaise électrique, un pneu ou une robe, vus par le pop art ; ils ne sont même que cela : immédiatement et exhaustivement identifiables, nous enseignant par là que l’identité n’est pas la personne : le monde futur risque d’être un monde d’identités, mais non de personnes.

We must realize that if Pop Art depersonalized, it does not make anonymous: nothing is more identifiable than Marilyn, the electric chair, a tire, or a dress, as seen by Pop Art; they are in fact nothing but that: immediately and exhaustively identifiable, thereby teaching us that identify is not the person: the future world risks being a world of identities, but not of persons.

{ Roland Barthes, Cette vieille chose, l’art, 1980 }

art { Andy Warhol, Foot and Tire, 1963-64 }

related { David Cronenberg on Foot and Tire }

art, roland barthes, warhol | March 8th, 2014 4:56 am

art, food, drinks, restaurants | February 19th, 2014 1:23 pm

There are two basic critical responses to today’s art market. One argues that the market has nothing to do with art, and that whatever happens in the market is irrelevant to the actual content, meaning and love of art. Art is to the art market as sailing is to the business of hawking mega-yachts to multibillionaires. The other view, succinctly stated by Perl, is more pessimistic: The art market is ruining art, spiritually and as a cultural practice.

{ Washington Post | Continue reading | via gettingsome }

art, economics | February 9th, 2014 9:08 am

art, drugs | January 18th, 2014 8:58 am

Of all the modern artist-curator-collectors, one stands out for the eccentricity and extremity of his habit. Viktor Wynd is the grandson of the novelist Patrick O’Brian (who himself wrote a biography of perhaps the greatest collector of the 18th century, Sir Joseph Banks). His Little Shop of Horrorsin Hackney, London, presents an up-to-date collection of curiosities. Visitors are greeted by more taxidermied beasts, from crows to hyenas; the faint-hearted are advised not to proceed downstairs, into Wynd’s dim and dungeon-like cellar, which contains two-headed babies and antique pornography. (There’s a long tradition of such shock exhibits – guests arriving at the home of the celebrated 18th-century anatomist and collectorJohn Hunter were greeted by the preserved erect penis of a hanged man in his hallway.)

{ Guardian | Continue reading }

art, taxidermy, visual design | January 14th, 2014 10:56 am

art | November 27th, 2013 12:50 pm

Research in recent years has suggested that young Americans might be less creative now than in decades past, even while their intelligence — as measured by IQ tests — continues to rise.

But new research from the University of Washington Information School and Harvard University, closely studying 20 years of student creative writing and visual artworks, hints that the dynamics of creativity may not break down as simply as that.

Instead, it may be that some aspects of creativity — such as those employed in visual arts — are gently rising over the years, while other aspects, such as the nuances of creative writing, could be declining. […]

The review of student visual art showed an increase in the sophistication and complexity both in the designs and the subject matter over the years. The pieces, Davis said, seemed “more finished, and fuller, with backgrounds more fully rendered, suggesting greater complexity.” Standard pen-and-ink illustrations grew less common over the period studied, while a broader range of mixed media work was represented.

Conversely, the review of student writing showed the young authors adhering more to “conventional writing practices” and a trend toward less play with genre, more mundane narratives and simpler language over the two decades studied.

{ University of Washington | Continue reading }

art, ideas, psychology | November 15th, 2013 12:04 pm

Francis Bacon’s 1969 triptych, “Three Studies of Lucian Freud,” sold for $142.4 million at Christie’s, described as the highest price ever paid for an artwork at auction. […]

Sometime in the 1970s the three panels were sold separately. The right-hand panel was bought by a collector in Rome who spent 20 years trying to reunite the triptych. He bought the middle panel from a Paris dealer in the early 1980s. Then, in the late ‘80s, he bought the left and final panel from a collector in Japan. It is also one of just two full-length triptychs that Bacon painted of Freud — the other, from 1966, is missing.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

previously { List of most expensive paintings }

Francis Bacon, art, economics | November 12th, 2013 8:15 pm

flashback, music, warhol | October 28th, 2013 11:07 am

warhol | October 10th, 2013 11:17 am

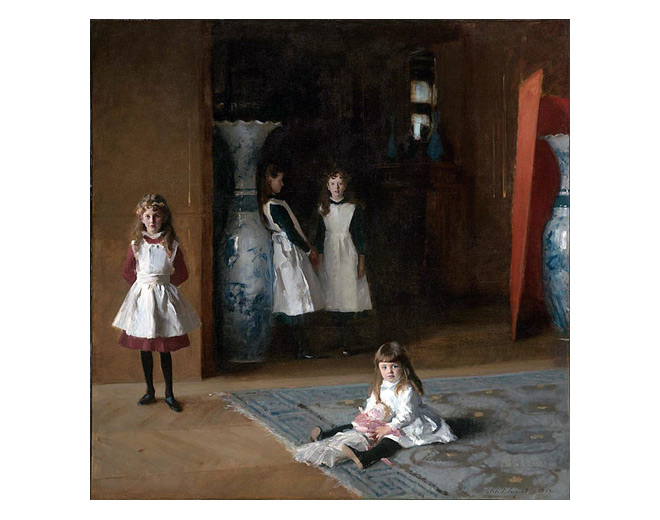

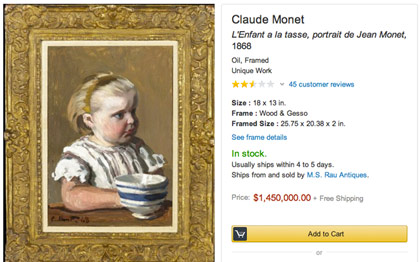

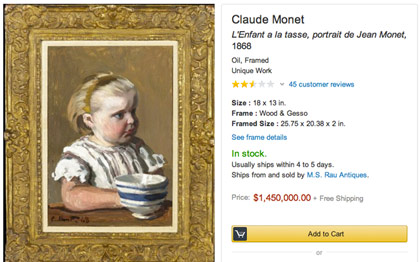

I purchased this product and sent it back immediately. The moment I took it out of the wrapping, I knew there was a problem, but I couldn’t quite put my finger on it.

Then I did put my finger on it. It felt a bit weird and when I started picking at it some of the paint flaked off. Cheap materials.

Anyhow, I may not be a member of the cognoscenti, but I have several Thomas “the Painter of Light” Kinkade paintings, so I know art. First of all, shouldn’t the lines be straight? It’s way too blurry and it hurts my eyes just to look at it. You know what also hurts my eyes? That little girls face. It looks like she has rosacea or something. And why is the girl so sad?!? Thomas Kinkade paintings are happy and joyful. This painting is just a bummer.

Save yourself a lot of disappointment and $1,448,500 and just get yourself a nice Kinkade lithograph. You’ll be glad that you did.

{ Customer Review/Amazon | Continue reading }

related { Amazon Enters Art World; Galleries Say They Aren’t Worried }

related { The utility of bad art }

art, economics, haha, technology | August 7th, 2013 11:45 am

If we — art dealers, collectors, writers and experts — all agree a particular work has value, it surely does, irrespective of its cost of production, utility and purpose.

In that sense a lot of the art market fuses the core characteristics of both Bitcoin and the gold market.

Though, of course, art, unlike Bitcoin and gold, is not scarce. Certain works of established artists, especially those who are no longer living, are scarce. Only forgeries can threaten supply in that case. But overall there are no barriers of entry. New assets can always be produced.

Consequently, regulating supply is down to the tight and clubby world of the art dealer and auctioneer network.

{ FT | Continue reading }

Art, then, is very similar to venture capital, insofar as who you know matters — and also insofar as both markets go to great lengths to hide natural valuation fluctuations. “Down rounds” are if anything even more harmful to an artist than they are to a startup: galleries will, as a rule, drop an artist before selling her art for less than she was charging at her previous show. The reason is entirely to protect the gallery’s own credibility: the gallery wants collectors to see it as a place where they can buy art which is going to rise in value, and as a result it will do everything in its power to make it look as though the work of all of its artists is only ever going up in price rather than down.

{ Salmon/Reuters | Continue reading }

art, economics | July 22nd, 2013 9:04 am

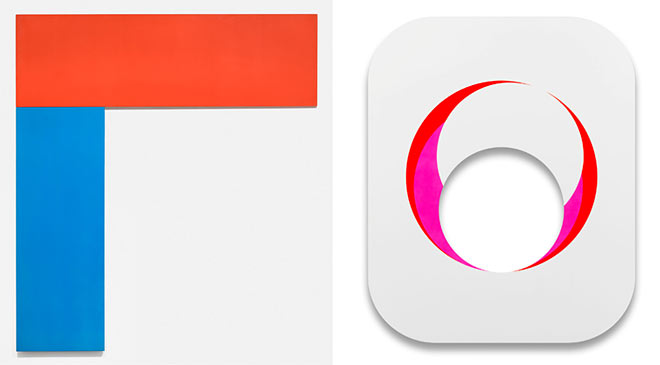

{ 1. Ellsworth Kelly, Chatham VI: Red Blue, 1971 | Oil on canvas, two joined panels | MoMA until Sept. 8, 2013 | 2. Gerold Miller, instant vision 143, 2012 | lacquered aluminum }

Ellsworth Kelly, art | June 11th, 2013 11:28 am

photogs, warhol | June 3rd, 2013 9:14 am