art

L.L. went to hell, gonna rock the bells

On July 16, 2012, a painting by a little-known artist sold at Christie’s for $74,500, nearly ten times its high estimate of $8,000. The work that yielded this unexpected result — an acrylic teal-hued painting of a rocky coast called “Nob Hill” — was not the work of a 20-something artist finishing up his MFA. It was a painting created in 1965, and the artist, Llyn Foulkes, is 77 years old and has been working in relative obscurity in Los Angeles for the past 50 years. In March, the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles mounted a retrospective of his work, which will travel to the New Museum in June, marking the first time Foulkes will have had a retrospective at a New York museum. […]

The new interest in older artists isn’t just about scholarly rediscovery. The interest has less to do with the necessity of unearthing historical material to understand an artist’s career arc and more to do with feeding an insatiable market. “Unlike the past model where most galleries hosted one new exhibition every four to six weeks, many galleries now have two or more new exhibitions every turn-over,” said Todd Levin, and art advisor and director of Levin Art Group. “There’s a increasing need to fill the constantly expanding number of exhibition opportunities.”

Today, there are some 300 to 400 galleries in New York compared with the roughly 70 galleries in New York in 1970. As for the number of shows galleries mount each year, that has likewise increased: Gagosian mounted 63 last year at its galleries worldwide, David Zwirner had 14 shows at its spaces in New York and London, and Pace had 36 across its three galleries in New York, Beijing, and London.

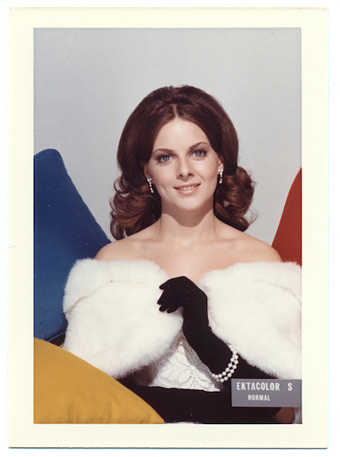

photo { Diane & Allan Arbus, Self-portrait, 1947 }

‘There is always some madness in love. But there is also always some reason in madness.’ –Nietzsche

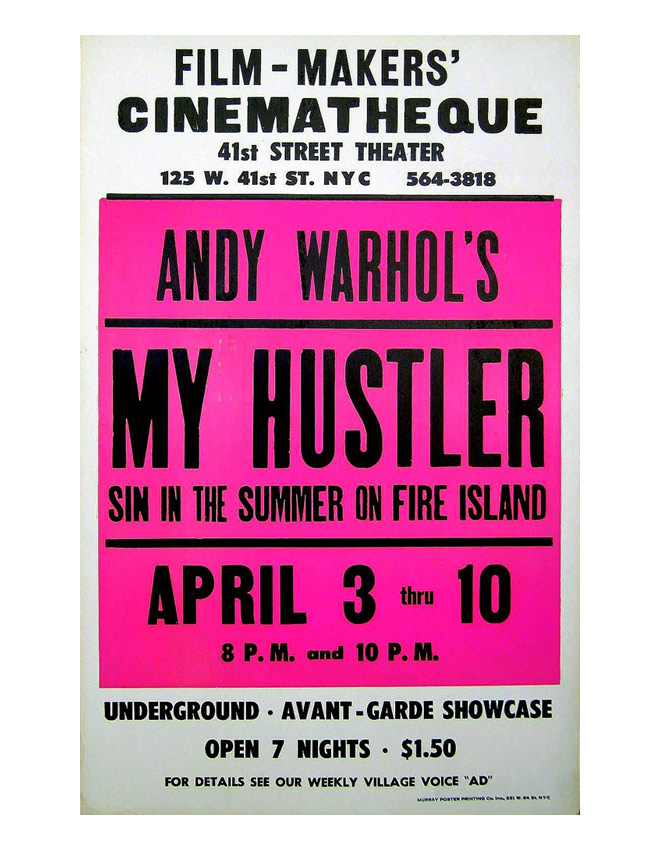

Andy Warhol took the subject of homosexual obsession to the big screen [in 1965]. The film was “My Hustler.” […]

By the mid-1960s, the movie taboo against homosexuality was down. But progressive depictions of gays (let alone lesbians) were rarities. In American movies, gay characters were portrayed as deviant misfits who inevitably met with societal scorn or tragedy (usually suicide). British films like “Victim” and “A Taste of Honey” were somewhat more open-minded in providing sympathetic (if epicene) depictions of gays.

“My Hustler” was radically different because it was not the least bit apologetic of the gay lifestyle. While the film dabbled in stereotypes (the bitchy queen, the rough trade call boys, even the fag hag best friend), no one was shown as a victim, let alone a freak. It was a raw, honest vision of a portion of the gay world which movie audiences never witnessed before.

Warhol was not, by any stretch, a polished filmmaker. His films were unsophisticated in their technique and production values were painfully low. In fact, “My Hustler” consists of two unbroken shots running 33 minutes each (the length of a 1,200 foot reel of 16mm film). While the visual aspect may seem stagnant, the film’s imagery and wall-to-wall talk makes its feel as if one if literally a voyeur to the mini-drama at hand.

“My Hustler” takes place on the Labor Day weekend at the beachfront Fire Island home of a wealthy and not-young queen (Ed Hood). He called a New York Dial-a-Hustler service and was sent a tall, muscular blonde hunk (Paul America). The film finds the older man on his deck watching his leased boytoy reclining on the beach. It is quite a sight to behold, as the hustler rubs suntan oil on his body and whittles with a piece of wood. And speaking of pieces of wood, the guy’s tight bathing suit leaves little to the imagination.

This scene is interrupted by two uninvited guests: Genevieve, the rich and bored socialite (Genevieve Charbon), and Joe, a late-30s hustler (Joe Campbell). The three sit on the deck and talk/bitch/dish among themselves about the stud in the sand. The camera pans back and forth between the deck trio and the hustler (there are no edits – just a continuous run of the camera). For long periods, the camera is fixated on the hustler while the others talk on the soundtrack. Joe claims to know the hustler, Genevieve states she can charm the guy with her sex appeal, and their mincing host belittles both of them with acidic camp remarks (he calls Genevieve a “fag hag” and calls Joe “the sugar plum fairy” – a line that Lou Reed would use in “Walk on the Wild Side”). All three make blunt comments about the object of their gaze (ranging from whether he is a real blonde to fantasizing about the length and width of what the bathing suit is barely concealing). Genevieve eventually makes her move and invites the hustler to go swimming with her.

‘If you receive a little money for this, a little money for that, everything becomes mediocre.’ –Salvador Dalí

The U.S. District Court in the Southern District of New York dismissed collector Jonathan Sobel’s lawsuit against photographer William Eggleston. […]

The lawsuit was spurred by Christie’s sale last March of 36 poster-size, digital prints of images that Eggleston had shot in the Mississippi Delta more than 30 years ago. Some were created from negatives he had never printed before, while others were based on iconic works, such as “Memphis (Tricycle).” (Sobel owns a 17-inch version of that photograph, for which he reportedly paid $250,000.) The sale was a massive success — by the time it was over, the large digital works accounted for seven of the artist’s top 10 prices. (The five-foot “Tricycle” came in on top, selling for a record $578,500.)

For Sobel, who owns 190 Eggleston works, the success of the sale was part of the problem. “The commercial value of art is scarcity, and if you make more of something, it becomes less valuable,” he told ARTINFO last April.

The judge disagreed. Egggleston may have profited from the Christie’s sale, she concluded, but not at Sobel’s expense. Eggleston could be held liable only if he created new editions of the limited-edition works in Sobel’s collection using the same dye-transfer process he used for the originals — a move that would directly deflate their value. In this case, however, Eggleston was using a new digital process to produce what she deemed a new body of work.

Rare lamps with faint rainbow fans

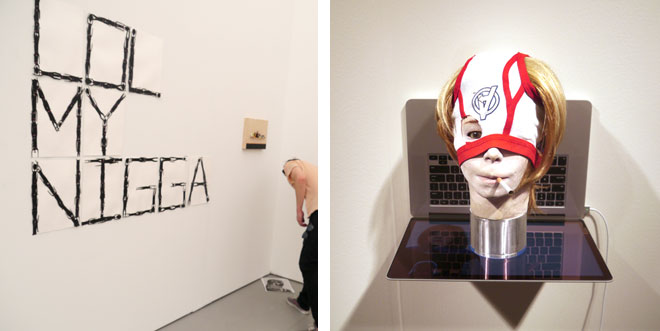

It seems to me that MFA programs have become a tool of indoctrination that has had an unprecedented homogenizing effect on artistic practices worldwide, an effect that is now being replicated with curatorial and critical writing programs. […]

The market of art is not merely a bunch of dealers and cigar-smoking connoisseurs trading exquisite objects for money behind closed doors. Rather, it is a vast and complex international industry of overlapping institutions which jointly produce artworks’ economic value and support a wide range of activities and occupations including training, research, development, production, display, documentation, criticism, marketing, promotion, financing, historicizing, publishing, and so forth. The standardization of art greatly simplifies all of these transactions. For a few years now I have experienced a certain sense of déjà vu while walking through art fairs or biennials, a feeling that many other people have also commented on: that we have already seen all these works that are supposedly brand new. We are experiencing the impact of contemporary art as a globally traded commodity that is produced, displayed, and circulated by an industry of specially trained professionals. […] This is not a new observation: I think Marcel Duchamp already fully understood this danger a hundred year ago. […]

Today it would be rather futile to try to reconstitute bohemia—the free-flowing, organic creative space—because it never really existed within the constellation of institutions of art, the art market, and the art academy. If Warhol’s Factory was an entry into art that enabled a group of people of very different backgrounds to enter a certain kind of productive modality (both within and in spite of the surrounding economy), it was a space of free play that no longer exists. Instead, what we have now are MFA programs: a standardization not even of bohemia, but only its promise. […]

As artists, curators, and writers, we are increasingly forced to market ourselves by developing a consistent product, a concise presentation, a statement that can be communicated in thirty seconds or less—and oftentimes this alone passes for professionalism.

photo { Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin }

If genetic material from another species is added to the host, the resulting organism is called transgenic. If genetic material from the same species or a species that can naturally breed with the host is used the resulting organism is called cisgenic.

Human cloning is the creation of a genetically identical copy of an existing or previously existing human. The term is generally used to refer to artificial human cloning; human clones in the form of identical twins are commonplace, with their cloning occurring during the natural process of reproduction. There are two commonly discussed types of human cloning: therapeutic cloning and reproductive cloning. Therapeutic cloning involves cloning adult cells for use in medicine and is an active area of research. Reproductive cloning would involve making cloned humans. A third type of cloning called replacement cloning is a theoretical possibility, and would be a combination of therapeutic and reproductive cloning. Replacement cloning would entail the replacement of an extensively damaged, failed, or failing body through cloning followed by whole or partial brain transplant.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

The biodesign movement builds on ideas in Janine Benyus’ trailblazing 1997 book Biomimicry, which urges designers to look to nature for inspiration. But instead of copying living things biodesigners make use of them. […]

Alberto Estévez, an architect based in Barcelona, wants to replace streetlights with glowing trees created by inserting a bioluminescent jellyfish gene into the plants’ DNA.

{ Smithsonian | Continue reading }

The most radical figure in the biodesign movement is Eduardo Kac, who doesn’t merely incorporate existing living things in his artworks—he tries to create new life-forms. “Transgenic art,” he calls it.

There was Alba, an albino bunny that glowed green under a black light. Kac had commissioned scientists in France to insert a fluorescent protein from Aequoria victoria, a bioluminescent jellyfish, into a rabbit egg. The startling creature, born in 2000, was not publicly exhibited, but the announcement caused a stir, with some scientists and animal rights activists suggesting it was unethical. […] Then came Edunia, a petunia that harbors one of Kac’s own genes.

‘I envy paranoids; they actually feel people are paying attention to them.’ –Susan Sontag

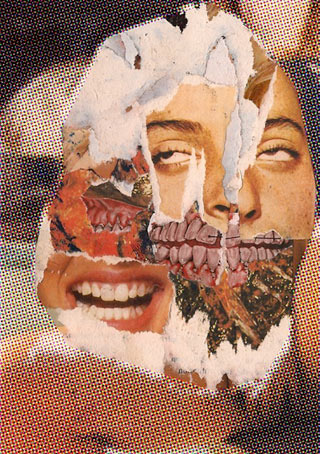

There is human DNA discarded carelessly all over New York City and one artist has been picking up a little of it and making facial reconstructions of what its owner might look like.

“I’ve worked with face recognition and speech recognition algorithms in the past, but I had never considered the emerging possibility of genetic surveillance; that the very things that make us human: hair, skin, saliva, become a liability as we constantly face the possibility of shedding these traces in public space, leaving artifacts which anyone could come along and mine for information,” Heather Dewey-Hagborg, a self-described information artist, wrote in a blog post introducing the concept that she has spent about a year working on. […]

She has taken DNA samples found on the streets of New York City from cigarette butts and gums and has been able to determine gender, ethnicity (based on the mother’s side) and eye color.

{ The Blaze | Continue reading | The Boston Globe | DNA could be used to visually recreate a person’s face }

Extraordinary popular delusions

I HAVE WRITTEN A LOT ABOUT ART. I NO LONGER DO BECAUSE THE ART WORLD IS TOO STUPID. I DON’T KNOW ANY WORDS THAT ARE SHORT ENOUGH OR LONG ENOUGH. IT’S A DEAD PRACTICE BUT FUN WHILE IT LASTED. WITH AFFECTION, Dave Hickey

{ The Brooklyn Rail | Thanks Rob }

“They’re in the hedge fund business, so they drop their windfall profits into art. It’s just not serious,” he told the Observer. […] “I hope this is the start of something that breaks the system. At the moment it feels like the Paris salon of the 19th century, where bureaucrats and conservatives combined to stifle the field of work. It was the Impressionists who forced a new system, led by the artists themselves. It created modern art and a whole new way of looking at things.”

{ Guardian | Continue Reading }

In 1999, he bought Munch’s Madonna for $11 million. In 2004, he bought Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living for $8 million. In 2006, he bought a Pollock for $52 million. In 2006, he bought de Kooning’s Woman III for $137 million. In 2007, he bought Warhol’s Turquoise Marilyn for $80 million. In 2010, he bought a Johns Flag for $110 million. There have been works by Bacon and Richter and Picasso and Koons. Probably only he knows how much he has spent. Someone on the internet estimates it at $700 million. […] Steven Cohen is in the news a lot lately. Prosecutors have accused seven former employees of his firm, SAC Capital, of insider trading. Three have pled guilty. Six others have been accused of insider trading while at other firms.

A plume of steam from the spout

The mystery of the art market is that some people would rather possess an object of marginal utility than the ultra-usable money they exchange for it. This is the mystery of all markets in which taste is transformed into appetite by a nonpecuniary cloud of discourse that surrounds the negotiation. There is always a tipping point at which one’s taste for Picasso or freedom or pinot noir becomes a necessity, or at least something one would rather not do without. The exact nature of this “something” is effervescent and indistinct.

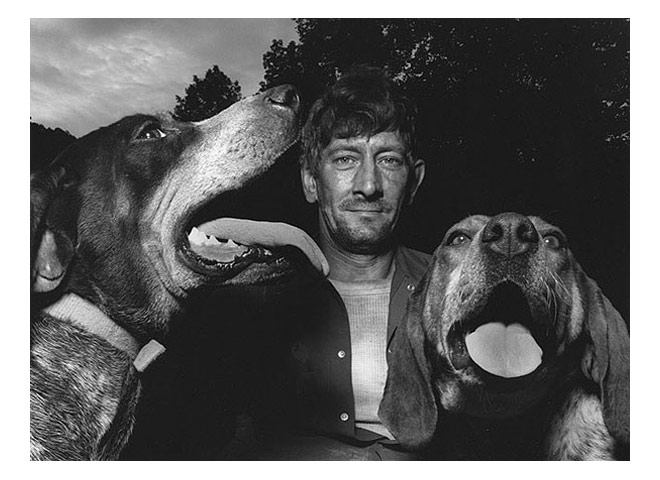

photo { Shelby Lee Adams }

I sometimes feel that I have nothing to say and I want to communicate this

Tightknit cabals of dealers and speculative collectors count on the fact that you will report record prices without being able to reveal the collusion behind how they were achieved. I get annoyed, for example, when one of Urs Fischer’s worst works (a candle sculpture depicting collector Peter Brant from 2010) makes $1.3m while Sherrie Levine’s classic bronze urinal, titled Fountain (After Marcel Duchamp) (1991), doesn’t even crack a million. The collision of financial interests behind 39-year-old Fischer, which includes Brant, François Pinault, Adam Lindemann, Larry Gagosian and the Mugrabi family, might explain the silly price. […]

Fraud and price-fixing aside, everyone involved in the art market knows that tax evasion is a regular occurrence and money laundering is a driving force in certain territories. However, your publication’s lawyers will quite rightly delete any mention of these illegalities. It’s impossible to prove them unless you can wiretap and trace money transfers. […]

Writing about the art market is painfully repetitive. […]

People send you unbelievably stupid press releases. […]

It implies that money is the most important thing about art.

Against a sea of troubles, torn by conflicting doubts, as one sees in real life

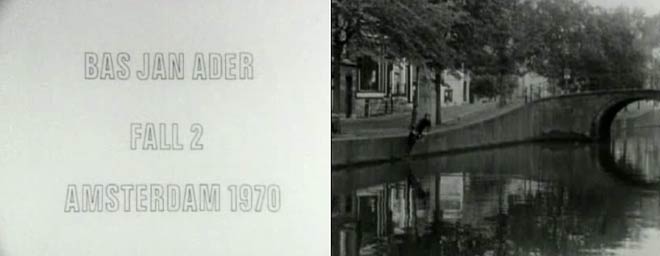

Bas Jan Ader (1942-1975) was a conceptual artist, performance artist, photographer and filmmaker. He lived in Los Angeles for the last 10 years of his life. […]

Ader was lost at sea while attempting a single-handed west-east crossing of the Atlantic in a 13 ft pocket cruiser, a modified Guppy 13 named “Ocean Wave.” The passage was part of an art performance titled “In Search of the Miraculous.” Radio contact broke off three weeks into the voyage, and Ader was presumed lost at sea. The boat was found after 10 months, floating partially submerged 150 miles West-Southwest of the coast of Ireland. His body was never found.

I love it when a chick uses LOLs in texts bc it means she’s usually easily impressed

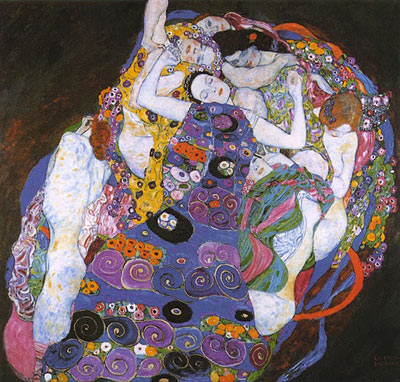

Five Ukrainian women, in an Ukrainian art museum. They are sleeping, or rather pretending to sleep, dressed up as Sleeping Beauty. Men come along and kiss them, on the lips, with each man allowed only one kiss. They have all signed legally binding contracts. If a woman responds to a kiss by opening her eyes and “waking,” she must marry the man. The man must marry the woman.

{ Marginal Revolution | Continue reading }

There are five Sleeping Beauties total; each takes turns, sleeping on the raised white satin bed for two hours at a time. […]

On September 5, the first Sleeping Beauty in Polataiko’s exhibition awoke to a kiss from another woman. Both of them were surprised. […]

Now the Sleeping Beauty must wed her “prince.” […] Gay marriage is not allowed in the Ukraine, however, so these two women will have to wed in a European country that does allow for same-sex marriage.

art { Gustav Klimt, The Virgin, 1913 }

The crossexamination proceeds re Bloom and the bucket. A lace bucket. Bloom himself Bowel trouble. In Beaver street.

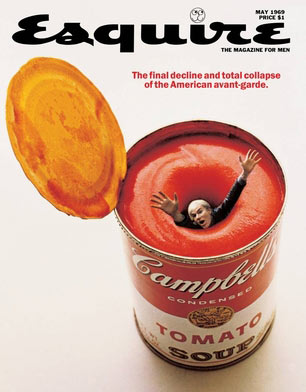

Warhol’s apotheosis as the savior of abstract painting has been coming for years now, ever since sundry dealers, curators, critics, and historians decided that his Shadows, Oxidations, Camouflages, and Rorschachs were in the great tradition of Kazimir Malevich, Jackson Pollock, and Barnett Newman. […]

Deitch begins by referring to abstraction as “a painting tradition that was once seen as essentially reductive” and “monolithic and doctrinaire”—but has “now become expansive.” In what sense were seminal abstract artists such as Kandinsky or de Kooning ever reductive? And what is more reductive than Warhol’s silly attempt at an all-over abstract painting included in this show, the bewilderingly boring 35-foot expanse of army surplus patterning entitled Camouflage?

Deitch would have us believe that Warhol had something to do with incorporating collage into abstract painting, although the truth is that Picasso and Braque were already doing that a century ago. There is nothing in this show that doesn’t have its origins in abstract painting long before Warhol got to work with his silkscreens.

She drew down pensive (why did he go so quick when I?) about her bronze over the bar where bald stood by sister gold

I sold them for about a thousand dollars in the ’70s, but now my gallerist, Matthew Marks, wants a lot for them. […] Matisse can’t do a line without it being a Matisse. I’m not that way. I do a lot of mediocre stuff, and if they’re not good, they go out.

bonus:

Life as the product of life

Scientists have now accurately predicted almost the whole genome of an unborn child by sequencing DNA from the mother’s blood and DNA from the father’s saliva.

artwork { Ellsworth Kelly, Red White, 1961 }

If masturbation really prevented prostate cancer there’d be no such thing as prostate cancer

One of the more memorable encounters in the history of modern art occurred late in 1961 when the period’s preeminent avant-garde dealer, Leo Castelli, paid a call at the Upper East Side Manhattan townhouse-cum-studio of Andy Warhol, whose pioneering Pop paintings based on cartoon characters including Dick Tracy, the Little King, Nancy, Popeye, and Superman had caught the eye of Castelli’s gallery director, Ivan Karp, who in turn urged his boss to go have a look for himself. Warhol, eager to make the difficult leap from commercial artist to “serious” painter, decades later recalled his crushing disappointment when Castelli coolly told him, “Well, it’s unfortunate, the timing, because I just took on Roy Lichtenstein, and the two of you in the same gallery would collide.”

Although Lichtenstein, then a thirty-eight-year-old assistant art professor at Rutgers University’s Douglass College in New Jersey, was also making pictures based on comic-book prototypes—an example of wholly independent multiple discovery not unlike such scientific findings as calculus, oxygen, photography, and evolution—he and Warhol were in fact doing quite different things with similar source material, as the divergent tangents of their later careers would amply demonstrate. By 1964, Castelli recognized his mistake and added the thwarted aspirant to his gallery roster, though not before Warhol forswore cartoon imagery, fearful of seeming to imitate Lichtenstein, of whom he always remained somewhat in awe.

In fact, what Lichtenstein and his five-years-younger contemporary Warhol had most in common was being the foremost exemplars of Cool among their generation of American visual artists. The first half of the 1960s was the apogee of what might be termed the Age of Cool—as defined by that quality of being simultaneously with-it and disengaged, in control but nonchalant, knowing but ironically self-aware, and above all inscrutably undemonstrative.