art

Banks must prove than bigger is better

Roy Lichtenstein’s 1961 painting of a man looking through a peephole sold for $43.2 million last night in New York, one of 13 records set at an auction of contemporary art by Christie’s International. (…) The Lichtenstein, the top lot, was one of 16 guaranteed artworks, 10 of which were backed by third parties, the auction house said. At the equivalent sale in 2010, only seven lots were guaranteed. (…)

The Lichtenstein, from the collection of Courtney Ross, the widow of former Time Warner Chief Executive Officer Steven J. Ross, had a high estimate of $45 million. She was guaranteed an undisclosed minimum price financed by third parties. The painting was acquired at auction in 1988 for $2.1 million.

Lichtenstein’s previous record of $42.6 million was set a year ago for “Ohhh… Alright…” (1964), depicting a sexy redhead on the phone.

And baby did his level best to say it for he was very intelligent for eleven months everyone said and big for his age and the picture of health

{ Torii Kiyonaga }

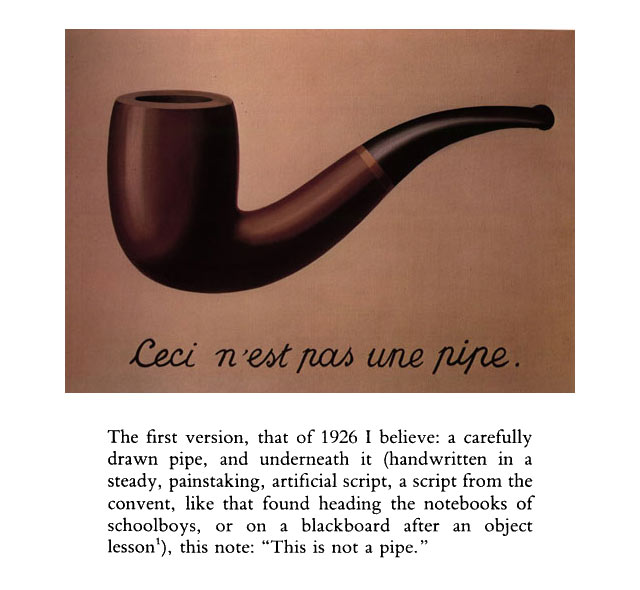

‘Truth does not belong to the order of power.’ –Michel Foucault

Are there really such things as artistic masterworks? That is, do works belong to the artistic canon because critics and museum curators have correctly discerned their merits? (…)

For the sake of this discussion let’s focus on two possible views: the first, call it Humeanism, is the view that when we make evaluative judgements of artworks, we are sensitive to what is good or bad. On this Humean view, the works that form the artistic canon are there for good reason. Over time, critics, curators, and art historians arrive at a consensus about the best works; these works become known as masterworks, are widely reproduced, and prized as highlights of museum collections.

However, a second view—call it scepticism—challenges these claims about the role of value in both artistic judgement and canon formation. A sceptic will point to other factors that can sway critics and curators such as personal or political considerations, or even chance exposure to particular works, arguing that value plays a much less important role than the Humean would lead us to believe. According to such a view, if a minor work had fallen into the right hands, or if a minor painter had had the right connections, the artistic canon might have an entirely different shape.

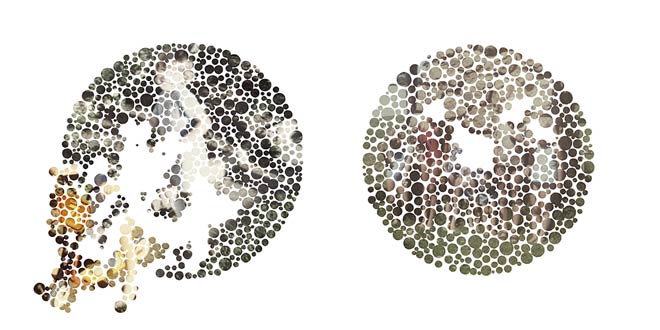

How is one to determine whether we are sensitive to value when we form judgements about artworks? In a 2003 study, psychologist James Cutting briefly exposed undergraduate psychology students to canonical and lesser-known Impressionist paintings (the lesser-known works exposed four times as often), with the result that after exposure, subjects preferred the lesser-known works more often than did the control group. Cutting took this result to show that canon formation is a result of cultural exposure over time.

arwtork { Marlene Dumas, Dead Girl, 2002 }

Damn your yellow stick. Where are we going?

A Waboba is a ball that bounces on water (wa-ter bo-uncing ba-ll). That makes it kind of unusual since a simple experiment will show that many balls do not bounce on water. And that raises an interesting question–how does the Waboba work?

Today we get an answer from Michael Wright at Brigham Young University in Utah and a few buddies. These guys videoed the way three balls interact with water when bounced.

A Superball, which is solid and so has a relatively small surface area for its mass, burrows deep into the water, even when it hits at a shallow angle. So it does not bounce.

A raquet ball, on the other hand,is hollow and so has a larger surface area ratio to mass ratio. When thrown at a shallow angle, it penetrates only a small distance into the water creating a depression in the surface through which it planes back onto the surface. So it rebounds a little.

The Waboba is hollow but it is also soft. (…) Because it is soft, the ball flattens into disc-shape when it hits the surface and this allows it to aquaplane efficiently across the surface. (…)

Why might this be useful? Wright and co don’t say in their video but the fact that one of the team is with the Naval Undersea Warfare Center in Newport might offer a clue.

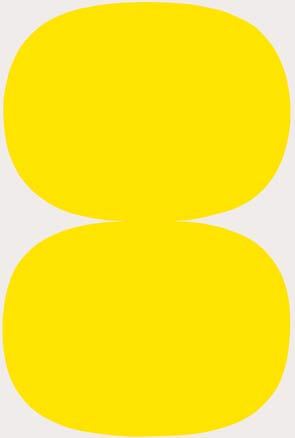

artwork { Ellsworth Kelly, Yellow White, 1961 }

Edward Smith: Would you like to see your pictures on as many walls as possible? Andy Warhol: Uh, no, I like them in closets.

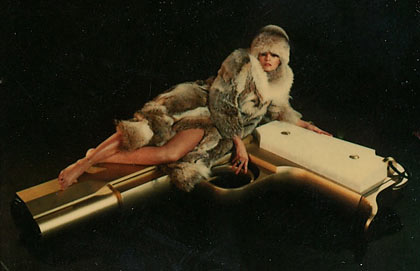

For most people, the term art crime invariably brings to mind images of daring museum break-ins, the theft of million-dollar paintings, and the stylish, sexy thieves who mastermind them.

In reality, high-value museum thefts are the exception rather than the rule. As retired FBI Art Crime Team Special Agent Bob Wittman recounts in his memoir, “art theft is rarely about the love of art or the cleverness of the crime, and the thief is rarely the Hollywood caricature. (…) Nearly all the art thieves I met in my career had one thing in common: brute greed. They stole for money, not beauty.”

For I am the size of what I see

This article looks at how previous practice of portraiture prepared the way for self-presentation on social networking sites. A portrait is not simply an exercise in the skillful or “realistic” depiction of a subject. Rather, it is a rhetorical exercise in visual description and persuasion and a site of intricate communicative processes. A long evolution of visual culture, intimately intertwined with evolving notions of identity and society, was necessary to create the conditions for the particular forms of self-representation we encounter on Facebook. Many of these premodern strategies prefigure ones we encounter on Facebook. By delineating the ways current practices reflect earlier ones, we can set a baseline from which we can isolate the precise novelty of current practice in social networking sites. (…)

Although a Velasquez portrait does not look much like a Facebook page, it fulfills many of the same functions. A portrait by Velasquez, hanging in the grand palace of Madrid, articulates an image of royal power and privilege to those permitted to view it, and thus reinforces the sitter’s right to certain prerogatives and respects.

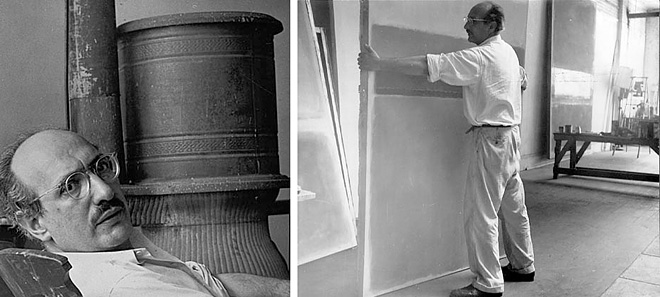

‘It is really a matter of ending this silence and solitude, of breathing.’ –Rothko

I’m going to break this down very simply, and as nonlibelously as possible.

On February 25, 1970, my mother received a call from Oliver Steindecker, Mark Rothko’s studio assistant, informing her that Rothko had committed suicide and was lying on the floor of his studio in a pool of blood. My mom took a cab from her house on East Eighty-Ninth to Rothko’s studio, twenty blocks south, and helped identify the body. She then took another cab uptown, to Rothko’s brownstone on East Ninety-Fifth, to tell Rothko’s estranged wife, Mell. She left a message with my father, who was, curiously, attending a funeral. Eventually he showed up as well, and helped to arrange Rothko’s funeral two days later. My mom was one month pregnant with me.

Five months later, Mell Rothko died unexpectedly of a heart attack, leaving their two children, Kate and Christopher, parentless. My mother was by now six months pregnant. Because of an inconsistency between the Rothkos’ wills, Kate, nineteen, became the ward of one Herbert Ferber, dentist-sculptor. Christopher, seven, became the ward of my parents. That arrangement ended badly. Christopher left my parents’ house the day before I was born.

photos { Henry Elkan, Mark Rothko in his West 53rd Street studio, 1953-54 }

Some guy hit my car fender the other day, and I said unto him, ‘Be fruitful and multiply.’ But not in those words.

At a glance, a painting by Jackson Pollock can look deceptively accidental: just a quick flick of color on a canvas.

A quantitative analysis of Pollock’s streams, drips, and coils, by Harvard mathematician L. Mahadevan and collaborators at Boston College, reveals, however, that the artist had to be slow—he had to be deliberate—to exploit fluid dynamics in the way that he did.

The finding, published in Physics Today, represents a rare collision between mathematics, physics, and art history, providing new insight into the artist’s method and techniques—as well as his appreciation for the beauty of natural phenomena. (…)

Pollock’s signature style involved laying a canvas on the floor and pouring paint onto it in continuous, curving streams. Rather than pouring straight from the can, he applied paint from a stick or a trowel, waving his hand back and forth above the canvas and adjusting the height and angle of the trowel to make the stream of paint wider or thinner.

Simultaneously restricted and inspired by the laws of nature, Pollock took on the role of experimentalist, ceding a certain amount of control to physics in order to create new aesthetic effects.

Instabilities in a free fluid jet can form in a few different ways: the jet can break into drops, it can splash upon impact with a surface, or it can fold and coil, as when a stream of honey lands on a slice of toast. The artist Robert Motherwell produced drips and splashes by flicking his brush; Pollock’s technique, on the other hand, is defined by the way a relatively slow-moving stream of paint falls onto the canvas, producing trails and coils.

In a sense, the authors note, Pollock was learning and using physics, experimenting with coiling fluids quite a bit before the first scientific papers on the subject would appear in the late 1950s and ’60s.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading | More: The Physics of Jackson Pollock’s Art }

painting { Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1948-1949 }

I ain’t got no money, I ain’t like those other guys you hang around

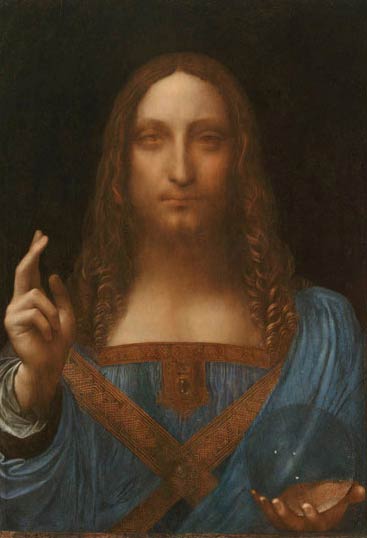

Every few weeks, photographs of old paintings arrive at Martin Kemp’s eighteenth-century house, outside Oxford, England. (…) Kemp scrutinizes each image with a magnifying glass, attempting to determine whether the owners have discovered what they claim to have found: a lost masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci.

Kemp, a leading scholar of Leonardo, also authenticates works of art—a rare, mysterious, and often bitterly contested skill. His opinions carry the weight of history; they can help a painting become part of the world’s cultural heritage and be exhibited in museums for centuries, or cause it to be tossed into the trash. His judgment can also transform a previously worthless object into something worth tens of millions of dollars. (His imprimatur is so valuable that he must guard against con men forging not only a work of art but also his signature.)

painting { Leonardo’s ‘lost’ Christ, sold for £45 in 1956, now valued at £120m | Guardian | full story }

I don’t believe in an afterlife, although I am bringing a change of underwear

Honey Space presents “Panties For Diamonds - A Psychodramatic Audition For Love In The Age Of Abandonment,” the New York debut of collaborative team INNER COURSE.

In this installation and three-act performance, Ms. Kleinpeter and Ms. Lopez flirt with antiquated methods of psychological inquiry within an environment generated by their analysis of the Other. Herein Actors/Audience become emotional accomplices in an unscripted narrative through role-play, interrogation and Softing. Participants will be guided through an assortment of exercises designed to cleanse the palate of perception - inviting new space to permeate.

INNER COURSE performs Tuesday through Saturday from 1-6 pm. Appointments may be booked at innercourse@honey-space.com.

related { Begging for change on Houston Street nude, browsing books at the NYU Library nude, buying a street hot dog nude – photographer Erica Simone created this series of self-portraits exposing herself all over New York City doing typical New York City things. | Animal NY | photos }

I used to have a pony, on Coney Island. It got hit by a truck.

{ photos by Jeremy Hu | Art Basel, June 2011 | Artist? }

The ones we rub under our arms

If art is a kind of lying, then lying is a form of art, albeit of a lower order—as Oscar Wilde and Mark Twain have observed. Both liars and artists refuse to accept the tyranny of reality. Both carefully craft stories that are worthy of belief—a skill requiring intellectual sophistication, emotional sensitivity and physical self-control (liars are writers and performers of their own work). Such parallels are hardly coincidental, as I discovered while researching my book on lying. Indeed, lying and artistic storytelling spring from a common neurological root—one that is exposed in the cases of psychiatric patients who suffer from a particular kind of impairment.

A case study published in 1985 by Antonio Damasio, a neurologist, tells the story of a middle-aged woman with brain damage caused by a series of strokes. She retained cognitive abilities, including coherent speech, but what she actually said was rather unpredictable. Checking her knowledge of contemporary events, Damasio asked her about the Falklands War. This patient spontaneously described a blissful holiday she had taken in the islands, involving long strolls with her husband and the purchase of local trinkets from a shop. Asked what language was spoken there, she replied, “Falklandese. What else?”

In the language of psychiatry, this woman was ‘confabulating’. Chronic confabulation is a rare type of memory problem that affects a small proportion of brain-damaged people. In the literature it is defined as “the production of fabricated, distorted or misinterpreted memories about oneself or the world, without the conscious intention to deceive”. Whereas amnesiacs make errors of omission—there are gaps in their recollections they find impossible to fill—confabulators make errors of commission: they make things up. Rather than forgetting, they are inventing.

‘Everything in life is somewhere else, and you get there in a car.’ —E. B. White

Friday, August 12, 1988. On the sidewalk outside 57 Great Jones Street, the usual sad lineup of crack addicts slept in the burning sun. (…) In the months before his death, Basquiat claimed he was doing up to a hundred bags of heroin a day.

images { Odette England }