art

And I beat me a billy from an old French horn

People who are more aware of their own heart-beat have superior time perception skills.

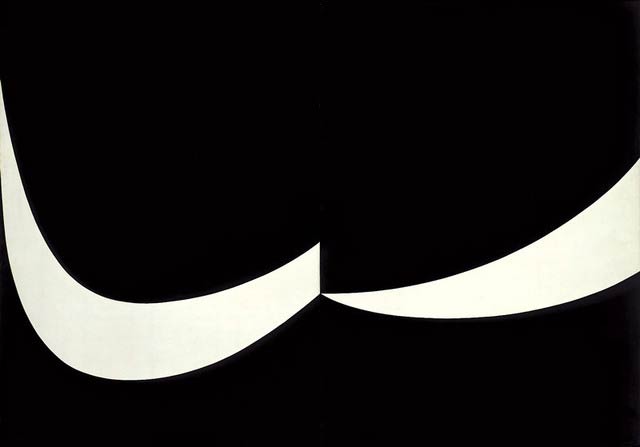

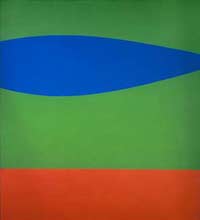

artwork { Ellsworth Kelly, Atlantic, 1956 | Oil on canvas on two panels }

On the dick like they heard I ghostwrite for P Diddy

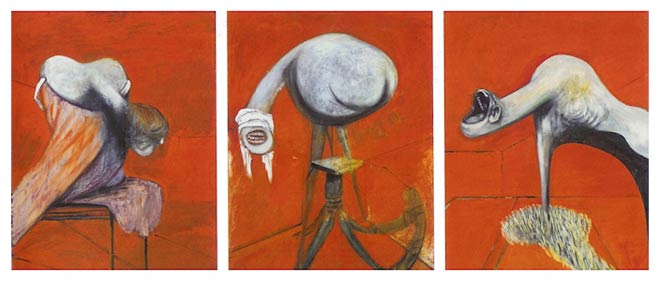

{ Francis Bacon, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, 1944 }

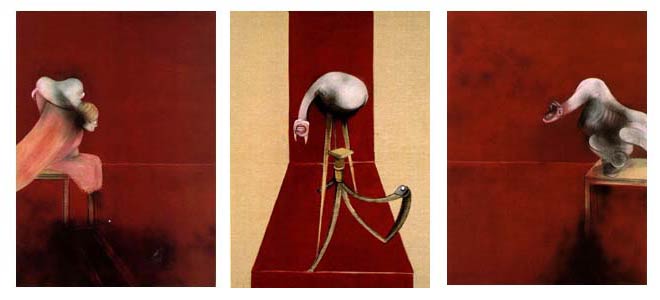

{ Francis Bacon, Second Version of Triptych 1944, 1988 }

Second Version of Triptych 1944 is a 1988 triptych painted by the Irish-born artist Francis Bacon. It is a reworking of Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, 1944, Bacon’s most widely known triptych, and the one which established his reputation as England’s foremost post-war painters. Bacon often painted second versions of his major paintings. In 1988, Bacon completed this near copy of the Three Studies. At 78 × 58 inches, this second version is over twice the size of the original, while the orange background has been replaced by a blood-red hue. His reason for creating this rework remain unclear, although Bacon did say to Richard Cook that he “always wanted to make a larger version of the first [Three Studies…]. I thought it could come off, but I think the first is better. I would have had to use the orange again so as to give a shock, that which red dissolves. But the tedium of doing it perhalps dissuaded me, because mixing that orange with pastel and then crushing it was an enormous job.”

Now I’ve got this real phat attitude because of all the hype

The American painter Barnett Newman once said that an artist gets from aesthetics what a bird gets from ornithology—nothing. (…)

There are things in our context that we readily recognize to be art because they are sufficiently like it in relevant respects—even though they may not “look like art” in every respect. What is this form of life in which this likeness can be seen? (…)

The notion that “vision itself has its history,” to use the words of Heinrich Wölfflin, has been one of the longest-lasting and deepest- seated principles of art history, even if it has sometimes been somewhat subterranean.

{ Whitney Davis, A General Theory of Visual Culture | Continue reading | PDF }

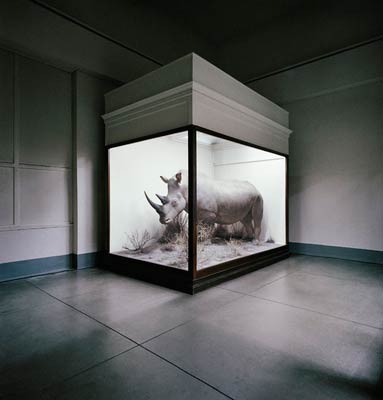

photo { Richard Ross, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, 1986 }

The lily at the end of the poem

{ Sandro Botticelli, Primavera, ca. 1482 | Enlarge/Zoom | There are 500 identified plant species depicted in the painting, with about 190 different flowers. Of the 190 different species of flowers depicted, at least 130 have been specifically named. | Wikipedia | Continue reading }

How’s your evening so far?

As of 2009 there were 3,020 museums in China, including 328 private museums (the American Association of Museums estimates 17,500 in the US). One hundred new museums are being added each year. In March the government made entry to museums of modern and contemporary art free. The torrid pace of museum development is part of a national drive to build cultural infrastructure and, as Cai Wu, the minister of culture, put it earlier this year in a published comment, “to establish a batch of world-famous cultural brands.”

“The next ten years should be a golden period for the development of every aspect of cultural industries in China,” said Ye Lang. “The country isn’t just satisfied with the economic achievements it had made,” the Xinhua news agency announced in January. “What it now needs is all-round cultural influence on an international scale.” The government backs these ambitions with a cultural outlay of $4.45bn in 2009, excluding construction costs.

photo { Mike Osborne }

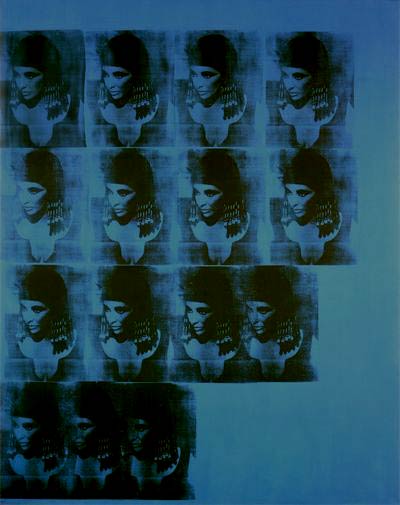

‘I’ve been married too many times. How terrible to change children’s affiliations, their affections — to give them the insecurity of placing their trust in someone when maybe that someone won’t be there next year.’ –Liz Taylor

{ Andy Warhol, Blue Liz As Cleopatra, 1963 | silkscreen ink and acrylic paint on canvas | Related: Jerry Saltz on Andy Warhol’s Portraits of Liz }

Queue de béton

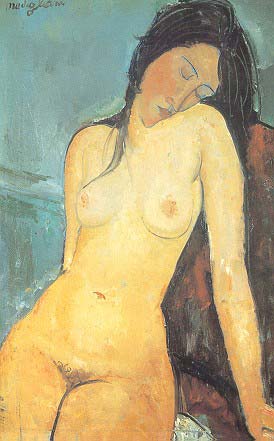

Among 20th-century artists, few can compare for sheer cinematic drama with the Italian painter and sculptor Amedeo Modigliani, “probably the most mythologized modern artist since Van Gogh,” according to the art historian Kenneth Silver. Scenes from the life of Modigliani might include “Modi” hobnobbing with Picasso in Montmartre, having a torrid affair with the married Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, and ending his long relationship with the English journalist Beatrice Hastings when her new lover drew a gun on him at a drunken party attended by Picasso, Matisse, and Juan Gris.

Modigliani drank heavily, used cocaine and hashish, and, a gorgeous hunk of a man despite his modest height of 5 feet 3 inches, fathered an indeterminate number of illegitimate children. (…)

“Sometimes, when drunk, he would begin undressing,” a friend reported in a typical account of Modigliani misbehaving, “under the eager eyes of the faded English and American girls who frequented the canteen … then display himself quite naked, slim and white, his torso arched.” When his life was cut short by tuberculosis at the age of 35, his final lover, Jeanne, eight months pregnant with their second child, threw herself out of a window.

{ Slate | Continue reading | More: Loving Modigliani thanks to Daniel }

artwork { Modigliani, Femme nue, 1916 }

no hair down there = gross

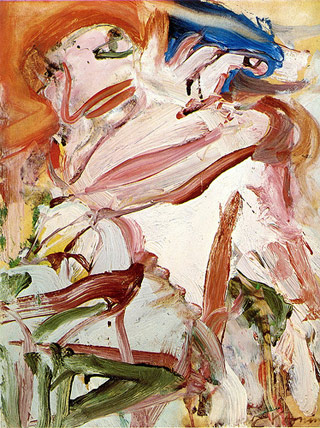

Does monocular viewing affect judgement of art? According to a 2008 paper by Finney and Heilman it does. The two researchers from the University of Florida inspired by previous studies investigating the effect of monocular viewing on performance on visual-spatial and verbal memory tasks, attempted to see what the results would be in the case of Art.

In particular, they recruited 8 right-eye dominant subjects (6 men and 2 women) with college education and asked them to view monocularly on a colour computer screen 10 painting with the right eye and another 10 with the left. None of the subjects was familiar with the presented paintings. Overall, each subject viewed 5 abstract expressionist and 5 impressionist paintings with each eye. (…)

Monocular viewing had significant effects only in paintings in the abstract expressionist style. Impressionist paintings yielded no differences.

painting { Willem de Kooning, Figure with Red Hair 1967 }

Per i fianchi, l’ho bloccata e ne ho fatto marmellata. Oh yeah.

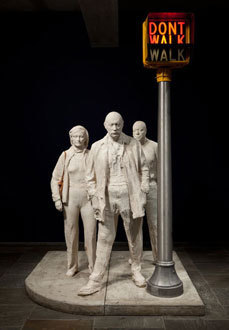

We know very well what sculpture is. And one of the things we know is that it is a historically bounded category and not a universal one. As is true of any other convention, sculpture has its own internal logic, its own set of rules, which, though they can be applied to a variety of situations, are not themselves open to very much change. The logic of sculpture, it would seem, is inseparable from the logic of the monument. By virtue of this logic a sculpture is a commemorative representation. It sits in a particular place and speaks in a symbolical tongue about the meaning or use of that place.

{ Rosalind Krauss, Sculpture in the Expanded Field, 1979 | Continue reading }

photo { Alvaro Sanchez-Montañes }

When you’ll next have the mind to retire to be wicked this is as dainty a way as any

The English language makes a distinction between blue and green, but some languages do not. Of these, quite a number, mostly in Africa, do not distinguish blue from black either, while there are a handful of languages that do not distinguish blue from black but have a separate term for green.

painting { Ellsworth Kelly, Blue Green Red, 1962–63 }

To persist in its own being

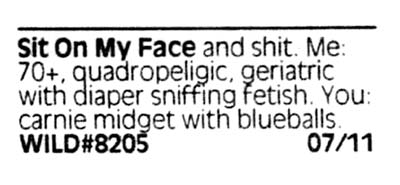

In his 1962 book “The Theory of the Avant-Garde” Renato Poggioli observed that “Like any artistic tradition, no matter how antitraditional it may be, the avant-garde also has its conventions.” The most conventional of modernist conventions has been the need to shock and offend, doing so, as the lingo has it, by “transgressing boundaries.” But once all the boundaries have been blurred, what’s left?

Since most folks are uncomfortable with explicit sexual conversation in public, obscenity laws limit such public conversation. But when artists create high quality and hence high status art with explicit sexual discussion, people are reluctant to let obscenity laws apply to it.

Something around your eyes, I don’t know

Cognition researchers should beware assuming that people’s mental faculties have finished maturing when they reach adulthood. So say Laura Germine and colleagues, whose new study shows that face learning ability continues to improve until people reach their early thirties.

Although vocabulary and other forms of acquired knowledge grow throughout the life course, it’s generally accepted that the speed and efficiency of the cognitive faculties peaks in the early twenties before starting a steady decline. This study challenges that assumption.

painting { Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas (Spanish for “The Maids of Honour”), 1656 | Las Meninas has long been recognised as one of the most important paintings in Western art history. Foucault viewed the painting without regard to the subject matter, nor to the artist’s biography, technical ability, sources and influences, social context, or relationship with his patrons. Instead he analyses its conscious artifice, highlighting the complex network of visual relationships between painter, subject-model, and viewer. For Foucault, Las Meninas contains the first signs of a new episteme, or way of thinking, in European art. It represents a mid-point between what he sees as the two “great discontinuities” in art history. | Wikipedia }

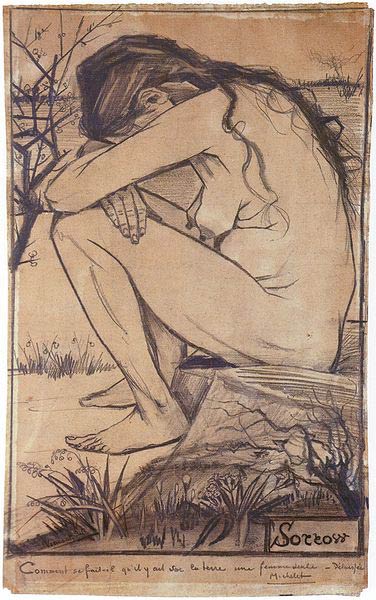

‘Love always brings difficulties, that is true, but the good side of it is that it gives energy.’ –Van Gogh

It’s hard to imagine some of Vincent van Gogh’s signature works without the vibrant strokes of yellow that brightened the sky in “Starry Night” and drenched his sunflowers in color. But the yellow hues in some of his paintings have mysteriously turned to brown — and now a team of European scientists has figured out why.

Using sophisticated X-ray machines, they discovered the chemical reaction to blame — one never before observed in paint. Ironically, Van Gogh’s decision to use a lighter shade of yellow paint mixed with white is responsible for the unintended darkening, according to a study published online Monday in the journal Analytical Chemistry.

“This is the kind of research that will allow art history to be rewritten,” because the colors we observe today are not necessarily the colors the artist intended, said Francesca Casadio, a cultural heritage scientist at the Art Institute of Chicago who was not involved in the work.

In a number of Van Gogh’s paintings, the yellow has dulled to coffee brown — and in about 10 cases, the discoloration is serious, said Koen Janssens, an analytical chemist at Antwerp University in Belgium who co-wrote the study.

drawing { Van Gogh, Sorrow, 1882 }

Your crutch, however, I am not. Thus spake Zarathustra.

{ Wallace Kirkland/LIFE | Robert Rauschenberg and His Wife Prepare Artwork, Circa 1951. Pete Wentz says: “Here Rauschenberg is at the forefront of what will become live art or street art. It’s interesting that he’s doing it inside, of course.” }

‘Life is uncertain. Eat dessert first.’ –Ernestine Ulmer

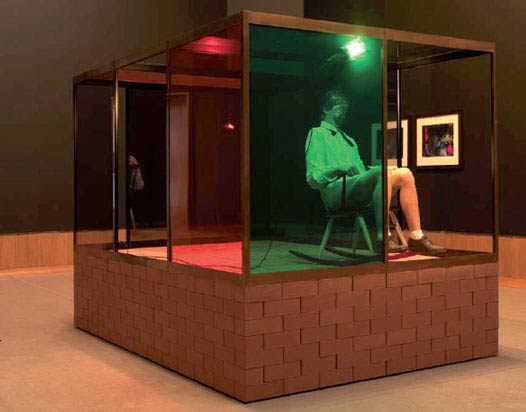

{ Andro Wekua, Wait to Wait, 2006 | 1 wax figure, 1 mechanized rocking chair, uncolored and colored glass, brazen aluminium, bricks, 4 collages, drawing | Andro Wekua interviewed by Maurizio Cattelan }

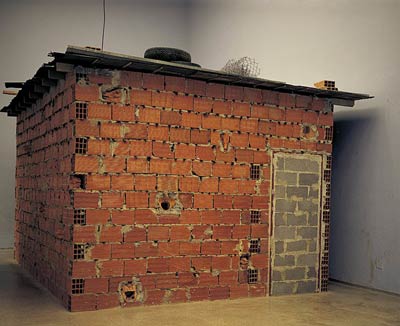

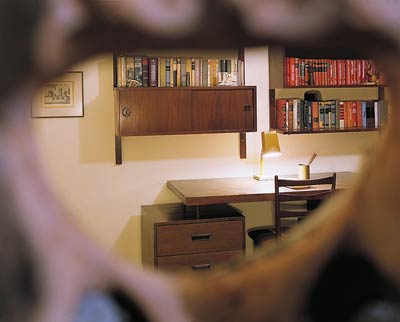

{ Meyer Vaisman, Green on the Outside, Red on the Inside, 1993 | Photos: Meyer Vaisman | Facebook }

‘Victory goes to those who will be able to create disorder without loving it.’ –Guy Debord

Jeff Koons, the creator of sculptures based on the image of a balloon dog, recently sent a cease-and-desist letter to a company selling bookends that represent a balloon dog and to the manufacturer of said dogs. It is doubtful Koons could win this one in court. We have all watched at a street fair as somebody twists long balloons into dogs or other animals. So what can Koons say is really his? The man has made his reputation as an appropriator—as an artist who borrows images and styles and ideas more or less wholesale from other more or less creative spirits. He himself has been sued for copyright violation four times, which may help to explain his eagerness to establish some legal precedent for appropriation as a form of creation. It is easy to make fun of Koons. But to the collectors, dealers, curators, critics, and historians who have invested time and in many cases considerable sums of money in his work and that of Warhol and other appropriators, the originality of the death of originality cannot be taken lightly. I think there is some concern that the artists will not finally escape what Sir Joshua Reynolds, in speaking about artists’ appropriations from other artists to the students at the Royal Academy in 1774, referred to as “the servility of plagiarism.” (…)

Jeff Koons, when accused of copyright infringement, tends to settle out of court. One has the impression that he prefers writing a check to actually discovering what a judge or a jury might have to say. But in his heart of hearts Koons probably feels that if Poussin became Poussin by stealing from Titian and Raphael, why on earth is he being bothered by questions of copyright and fair use?

{ The New Republic | Continue reading }

Balloon dogs everywhere can breathe a sigh of relief: SF’s Park Life store/gallery announced that artist Jeff Koons has dropped legal action against the sale of its balloon dog-shaped bookends.

{ Bay Citizen | Continue reading | Thanks JJ }

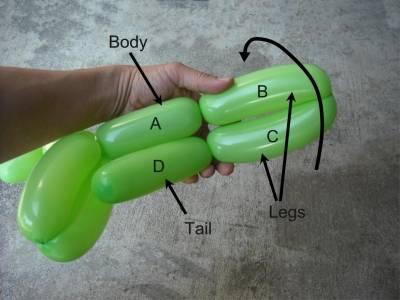

related { How to Make a Balloon Dog }

bonus:

The foolish one of the family is within. Haha! Huzoor, where’s he?

In the history of inkblots, the experiment of Hermann Rorschach [1884-1922] is the most famous moment: a controversial attempt to establish a scientific personality assessment based on ten standard Rorschach inkblots. Then comes Andy Warhol, who in the 1980s reconnects inkblots with the art that came before. He did these huge, very sexual, strange, hieratic paintings which he called ‘Rorschach Paintings’ - although they were, in fact, entirely of his own invention. At the opening a journalist asked him what they meant and Warhol - in that amazing, neutral, “I’m a mirror” way of his– said, “Oh, I made a mistake, I got that wrong. I thought the idea was that you make your own inkblots and the psychiatrist interprets them. If I’d known, I’d just have copied the originals!” (…)

there have been inkblot tests around for ages, but in the 19th century they took over from silhouettes as the parlour game, partly due to a German doctor and poet called Justinus Koerner, who was a friend of the German Romantics and was interested in the nascent science of psychology and such things. He’d write endless letters, and he doodled in them, and started playing around with inkblots. He was the one who worked out that you could make inkblots symmetrical by folding them over.

related { Rorschach Test – Psychodiagnostic Plates: The ten inkblots + Decryption }

image { John Waters, Director’s cuts }

I think flowers’ colors are brighter here than any place on earth and I don’t know whether it is the light that makes them seem so or whether they really are.

{ Carsten Höller, Soma | Museum Für Gegenwart, Berlin, until February 6th, 2011 | full story | more photos | designboom }