Nothing stokes the flames of love like a vision of you

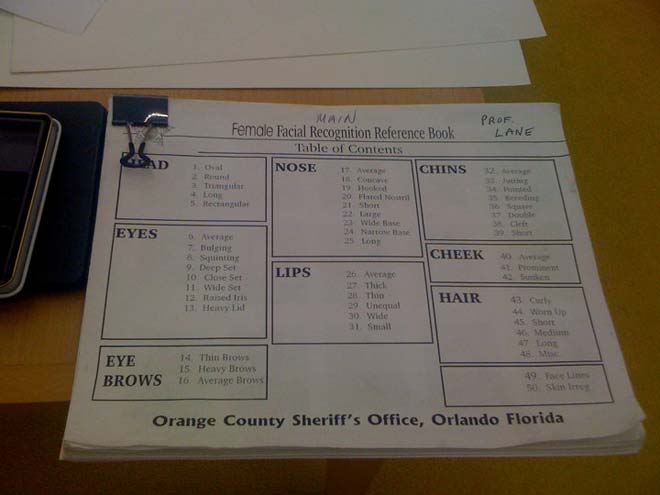

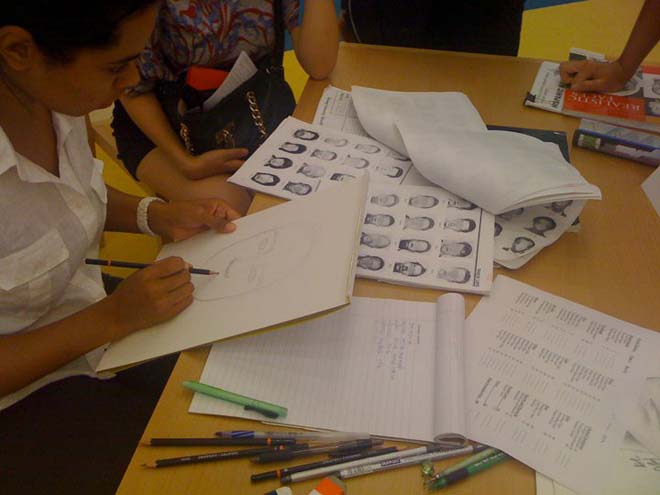

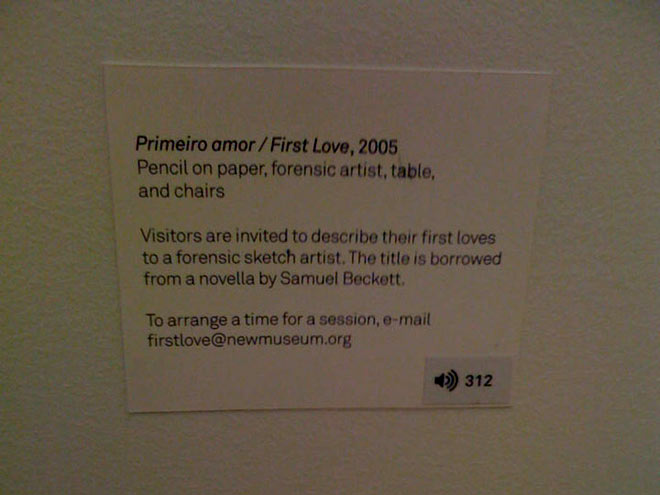

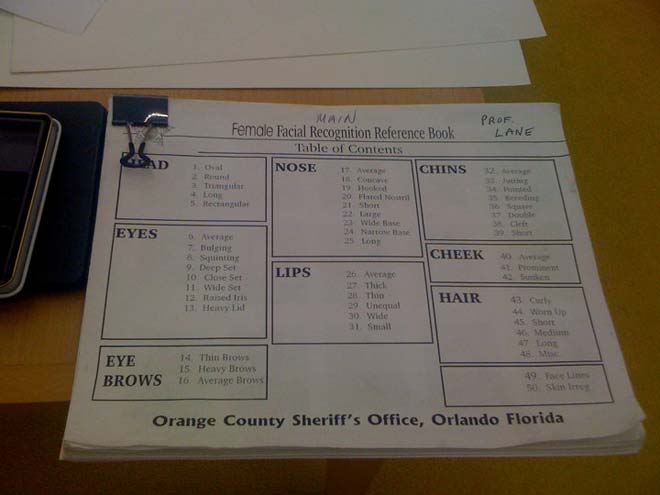

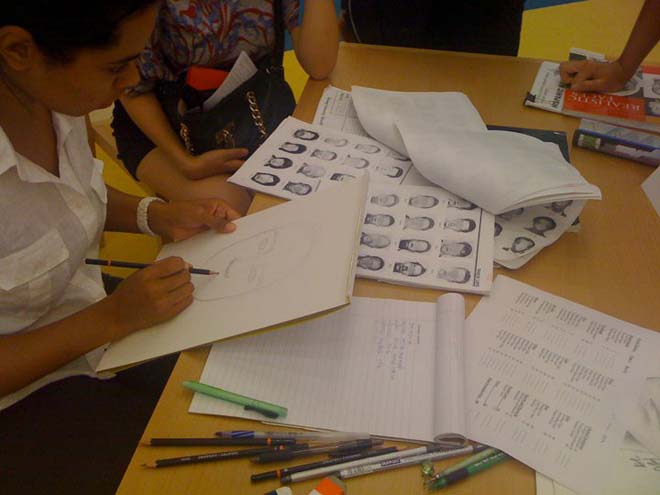

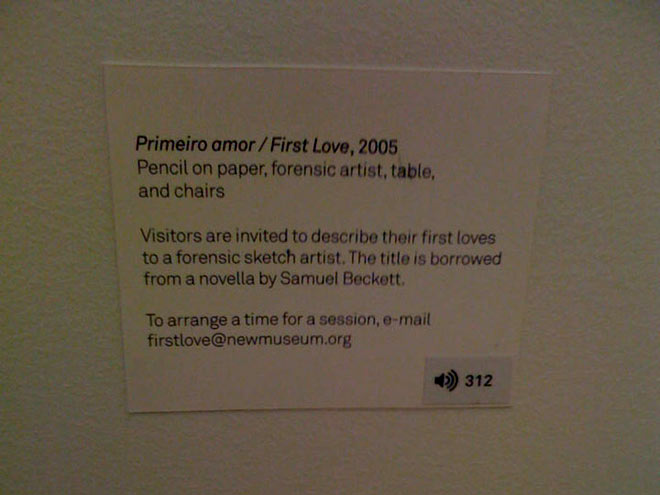

{ New Museum, NYC, Summer 2010 }

{ New Museum, NYC, Summer 2010 }

This article is based on a talk I gave at the recent John Cage exhibition in the Kettles Yard gallery in Cambridge. Cage is perhaps best known for his avant-garde music, particularly his silent 1952 composition 4′33″ but also for his use of randomness in aleatory music.

But Cage also used randomness in his art. The Kettles Yard exhibition featured wonderful film of assistants reading computer-generated random numbers off a list, which determined which of a row of stones were to be chosen, which brush to use, and the position of the stone on the paper; Cage finally paints around the stone, stands back and announces the results as “beautiful.” He also dictated the use of chance in the form of the exhibition, and Kettles Yard used computer-generated coordinates to determine the heights and positions of the pictures, removing and adding pieces during the exhibition using a random process.

Our brains appear to have an intrinsic response to “art for art’s sake,” researchers at Emory University School of Medicine have found.

Imaging research has revealed that the ventral striatum, a region of the brain involved in experiencing pleasure, decision-making and risk-taking, is activated more when someone views a painting than when someone views a plain photograph.

The images viewed by study participants included paintings from both unknown and well-known artists. (…)

The idea for the study was based on work by marketing experts Henrik Hagtvedt (now at Boston College) and Vanessa Patrick (now at the University of Houston). Hagtvedt and Patrick had investigated the “art infusion” effect, where the presence of a painting on a product’s advertising or packaging makes it more appealing.

The art world told us that anything could be art, so long as an artist said it was. Almost anyone who goes through a gallery door is likely to have heard about Duchamp and his urinal. The art world is less good at explaining how certain people get to be artists and decide what art is for the rest of us. This process of selection might not make aesthetic or philosophical sense, but it works anyway. It’s about power: whoever holds it gets to officiate and decide. The “art world” is a way of conserving, controlling and assigning this precious resource.

It is not surprising that theologians and artists clashed over the Last Supper. Common meals were the center of social life in Renaissance Europe, everywhere from ascetic, remote monasteries to bankers’ and cardinals’ lush gardens in the middle of Trastevere. And they were always a battleground of opposing ideals of austerity and consumption. (…)

But what should a Last Supper look like? What did Christ and the Apostles eat? And how much? When Jesus distributed pieces of bread, was it leavened or unleavened? What other foodstuffs had been on the table? Did the followers of Jesus eat lamb, as Jews normally did at Passover? Over the centuries—as an article in the International Journal of Obesity recently showed—artists made many different choices. Sometimes they put lamb on the table. But they also served fish, beef, and even pork in portions that grew over the centuries.

painting { Dirck van Baburen, Roman Charity, Cimon and Peres, ca. 1623 }

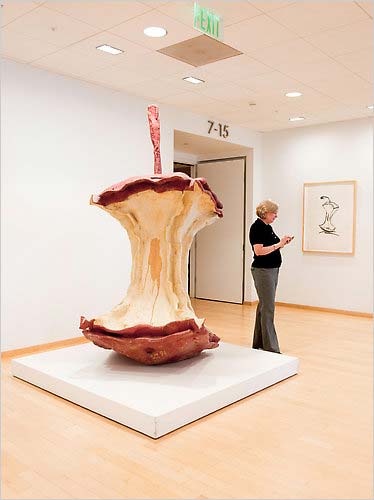

{ Our Imaging Services department is steadily building a comprehensive image archive of all works in the collection, while simultaneously managing more urgent photography requests, including those from outside the Museum. (…) Take a look at this sleek, smooth sculpture by Constantin Brancusi—a shimmering ovoid form seemingly floating in space. Would it ever strike you as one of the most difficult objects in our collection to photograph? Well, it is. | MoMA | full story }

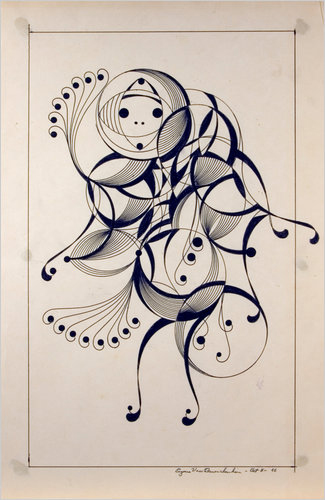

{ Von Bruenchenhein’s drawing made with ballpoint pens, rulers and French curves, 1965 | Von Bruenchenhein’s hyper-productive creative existence is receiving its first in-depth museum exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum. | NY Times | full story }

Casino-resort developer Steve Wynn is betting big on the art market this fall. Mr. Wynn has enlisted Christie’s to auction off a Roy Lichtenstein painting for at least $40 million at its major sale of contemporary art on Nov. 10 in New York.

The 1964 painting, “Ohhh…Alright…,” depicts a pixilated redheaded woman clutching a telephone. (…) Mr. Wynn bought the work from a New York gallery, Acquavella, a few years ago. Before that, the painting belonged to actor and writer Steve Martin. Mr. Martin confirmed he once owned the work; Mr. Wynn declined to comment.

“Ohh…Alright…” has never been auctioned off before, but it has been shown to collectors on the private marketplace, dealers say. Most notably, it was included in a not-for-sale show of the artist’s “Girls” series two years ago at New York’s Gagosian Gallery. (…)

At the market’s peak two years ago, Christie’s privately brokered the sale of another 1964 Lichtenstein redhead, “Happy Tears,” for roughly $35 million, up from the $7.1 million the auction house got for that same work six years earlier, according to Brett Gorvy, Christie’s international co-head of postwar and contemporary art.

{ Wall Street Journal | Continue reading }

No one except Wynn himself might have imagined it, but in the past two years, the Las Vegas resort mogul has become one of the world’s most successful art dealers/warehousers. Looking at the fruit of one large purchase Wynn made in March 1998 (just one of many acquisitions he or his company has made), he appears to be looking at a potential 40 percent to 50 percent appreciation on an investment of $50 million.

Beginning in November 1996, Mirage Resorts President and CEO Steve Wynn began collecting art for the opening of Bellagio, an upscale resort in Las Vegas. Yet even before Bellagio and the Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art opened in October 1998, Wynn had become an art dealer, trading the works he acquired.

While Wynn picked out art for his company to purchase, he also bought for himself. Most notable is a group of seven contemporary paintings for $50 million from New York dealer William Acquavella on March 9, 1998. The math (admittedly, somewhat speculative), shows that Wynn has sold three of the paintings for around $37 million and two others worth about $4 million for undisclosed prices. And he still owns two that are worth over a total of $20 million, easily. Here’s a list of the paintings in question and, where possible, information on what has become of them.

Robert Rauschenberg, Small Red Painting, 1954

Combine painting, ca. 28 x 21 x 5 in.

Wynn ‘98 valuation: $3.4 million

Sold after Bellagio opened

Buyer and sale price are unknownCy Twombly, Untitled, 1961

Acrylic, colored crayons and graphite on canvas, 40 x 58 in.

Wynn ‘98 valuation: $847,458

Sold before Bellagio opened

Buyer and price are unknownFranz Kline, August Day, 1957

Oil on canvas, 92 x 78 in.

Wynn ‘98 valuation: $2.5 million

Sold to PaceWildenstein, where it was for sale at $4 million

Presumed net to Wynn: around $3.2 millionRoy Lichtenstein, Torpedo…Los!, 1963

Oil on canvas, 68 x 80 in.

Wynn ‘98 valuation: $12.7 million

Sold spring ‘98 for around $14 million to Microsoft architect guru Charles SimonyiJasper Johns, Highway, 1959

Encaustic and collage on canvas, ca. 34 x 27 in.

Wynn ‘98 valuation: $9.3 million

Sold summer ‘99 for around $20 millionWillem de Kooning, Police Gazette, 1955

Mixed media on canvas, ca. 43 x 40 in.

Wynn ‘98 valuation: $11.9 million

Remains in Wynn’s collectionJackson Pollock, Frieze, 1953-55

Oil, enamel and aluminum paint on canvas, ca. 26 x 86 in.

Wynn ‘98 valuation: $9.3 million

Remains in Wynn’s collection

bonus:

videos { Wynn Las Vegas TV Commercial, 2005 | Encore Las Vegas TV Commercial, 2008 }

{ Yves Klein, Empreinte du fond d’une baignoire vide don’t l’eau avait été colorée de vermillion, COS 2, 1960 | Yves Klein Archives | Continue reading }

‘As I lay stretched upon the beach of Nice, I began to feel hatred for birds which flew back and forth across my blue sky, cloudless sky, because they tried to bore holes in my greatest and most beautiful work.’ –Yves Klein

Who is Yves Klein, and what’s the story behind his unearthly color? Lolling on a beach in 1947, a teenage Klein carved up the universe of art between him and two friends. Painter Arman Fernandez chose earth, Claude Pascal words, while Klein claimed the sky. (…)

Klein’s first public exhibit in 1954 featured monochrome canvases in several shades—orange, pink, yellow as well as blue—but the audience’s placid reception enraged him, as if it were “a new kind of bright, abstract interior decoration,” as Weitermeier puts it. Klein’s response was to double down exclusively on what he considered the world’s most limitless, enveloping color: blue [International Klein Blue].

With the help of Parisian paint dealer Edouard Adam, he suspended pure ultramarine pigment—the most-prized blue of the medieval period— in a synthetic resin called Rhodopas, which didn’t dull the pigment’s luminosity like traditional linseed oil suspensions. Their much-vaunted patent didn’t apply to the color proper, but rather protected Klein’s works made with the paint, which involved rolling naked ladies in the new hue and transferring their body-images to canvas.

Invitees to two simultaneous 1957 exhibits received an blue-drenched postcard in the mail, complete with an IKB postage stamp actually canceled by the French postal service (an authentic touch Klein probably bribed his postman for).

Photograph of a performance by Yves Klein at Rue Gentil-Bernard, Fontenay-aux-Roses, October 1960, by Harry Shunk

In one of the best-known photographs in art, the French artist Yves Klein projects himself confidently into space, seemingly as heavenbound as a Titian angel, while all unawares the banal figure of a cyclist goes about his earthbound business. The irony of Le saut dans le vide (Leap into the void, 1960) is that an image so faithful to Klein’s artistic quest should be a fake, a confection manufactured in the darkroom by him and the photographer who took the shot, Harry Shunk.

Klein’s performance, staged for a one-off newspaper he was planning, involved the taking of two pictures. First, Shunk photographed the street empty of all save the cyclist. Then Klein, a keen exponent of judo, climbed to the top of a wall and dived off it a dozen times — onto a pile of mats assembled by the members of his judo school across the road. The two elements were then melded to create the desired illusion.

The image, which has had a lasting influence on performance art, was expressive of Klein’s intent to explore the metaphorical void central to his work, a neutral zone free of prior prejudices. It was also a criticism of Nasa’s space travel plans, for Klein the ultimate folly of an over-materialistic world. Yet though the montage was executed under his direction, the presence of Shunk — who became a rather forgotten figure — should not be ignored.

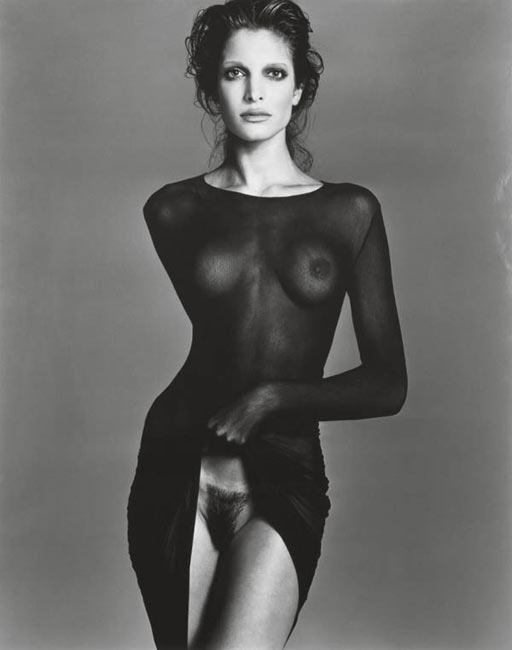

{ Richard Avedon, Stephanie Seymour, Model, New York City, 1992 | gelatin silver print, signed, numbered ‘5/5′ in pencil, copyright credit and reproduction title stamps (on the verso) 57¾ x 46in. (146.6 x 116.8cm.) | $182,500 | The stylist for this shoot was Polly Allen Mellon, the dress is by Comme des Garçons, Ms. Seymour’s hair is styled by Oribe, her make-up is by Kevin Aucoin. | Christie’s }

There is a contemporary art genre still under the radar of many collectors and dealers: performance art. Performance art is, however, finally coming in from the margins with a flood of prestigious exhibitions and museum initiatives that throw new light on a medium often seen as a relic of the 1970s. And anyway – how is it possible to speak of buying and selling, or collecting, an art form that has no object, only a process and an experience? (…)

At what point did acquiring performance art switch from owning objects associated with the actions, such as videos and photographs, to possessing the “idea” behind the piece? Berlin-based artist Tino Sehgal has evidently turned collecting criteria on their heads. He sells his performance art pieces by means of verbal transactions in the presence of a lawyer with no written contract. Instructions on how to re-enact his works are delivered literally by word-of-mouth, with collectors under strict orders never to photograph or video his “constructed situations”. Yet they sell in editions of four to six for $85,000 to $145,000 each, according to The Art Newspaper.

photo { Roy DeCarava, Dancers, 1956 }

{ It was just another day at the Gap, the clothing chain, where for many years much of the extraordinary art collection of the company’s founders, Don and Doris Fisher, has been hidden away in these ground-floor rooms. Although the collection includes more than 1,100 works, mostly from the 1960s on, they have been seen by relatively few people: Gap employees, the occasional museum tour group and those in the upper echelons of the art world who have the right connections. News media coverage has always been tightly restricted, and Mr. Fisher, who directed the Gap for more than 40 years until his death at 81 last September, refused to give interviews about his holdings for most of that time. | NY Times | Continue reading }

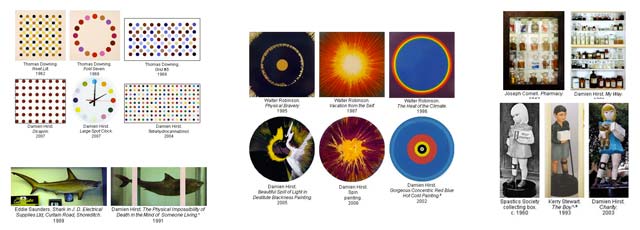

{ But who exactly bought what? Even Mr Hirst admits, “I’m still finding out.” Dealers acquired some works, but 81% of the buyers were private collectors purchasing directly. | How Damien Hirst grew rich at the expense of his investors | The Economist | full story }

{ The Art Damien Hirst Stole | more | Thanks Tim }