Alberto Giacometti’s six-foot-tall bronze Walking Man I sold at Sotheby’s London in February 2010 for the equivalent of $104.3 million, and was briefly (until overtaken this month by a Picasso) the most expensive artwork ever sold at auction. It remains, by far, the most expensive work available in multiple examples. The sculpture, cast by the artist himself in 1961, was reportedly bought by Lily Safra, widow of banker Edmund Safra. (…)

But by most people’s standards it is a very large sum of money; and in relation to the production cost of the sculpture it is an absurdly large sum of money. To make a copy of Walking Man I today (I am told by Morris Singer Foundry, which does much casting for artists in the UK) would cost in the region of $25,000, including the price of the bronze. If we allow for Giacometti’s time to make the piece, it does not substantially alter the enormity of the disparity between production cost and market price. Given that the sculpture exists in an edition of six, it would seem that, back in the early 1960s, Giacometti single-handedly created more than a half a billion dollars of goods, at today’s prices, in at most a few weeks. (…)

Writing about the Giacometti sale, the Australian journalist Andrew Frost posed the question that no doubt many people ask themselves even if they do not utter it out loud: “Since the material value of art is negligible, we’re paying for something — but what?”

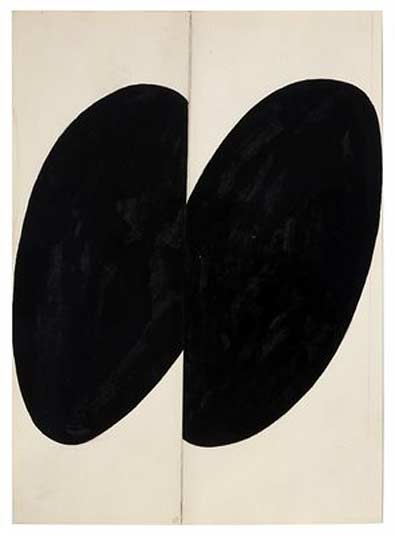

Pablo Picasso, legend has it, had an answer to this: you are paying for “a lifetime of experience.” But this explanation fails when we consider the market in work by Picasso himself. The most expensive works by Picasso that have been sold at auction are the 1932 Nude, Green Leaves and Bust, purchased recently for $106.5 million; and a 1905 Rose Period painting, Garcon a la Pipe, which was auctioned for $104.2 million in 2004. Allowing for inflation, the Garcon cost more in real terms than the Nude. Picasso, born in 1881, was roughly 24 years old when he painted it, and he eventually lived to 91: the art he produced in his old age, with a “lifetime of experience” behind him, is worth less, not more.

A sense of the disconnect between the production cost and market price of artworks has already become a part of modern consciousness. (…)

Recently a number of books have been published by economists who aim to reveal the mechanism that leads to the formation of staggering prices for art, especially modern art. As part of their analyses, these economists have attempted to define exactly what the quality or qualities are that collectors pay for. Among these books are Don Thompson’s The $12 Million Stuffed Shark, David W. Galenson’s Artistic Capital, and Olav Velthuis’s Talking Prices. Of course, theories of art can be more sophisticated than those proposed in the above books, but as a rule they don’t directly address the question “What are we paying for?” By applying the principle of Follow The Money, maybe we can arrive at an insight into art itself.

Thompson’s theory is that the price of the preserved shark to which his title alludes (a work by Damien Hirst) and of other expensive works of contemporary art is a reflection of “brand equity” produced by marketing and publicity. He compares explicitly the purchase of a “branded” artwork, i.e. one blessed by the gallery-auction-museum-press apparatus, to the purchase of a Louis Vuitton handbag, and suggests that branding is relied upon by buyers as a substitute for their own judgment, about which they feel insecure.

{ Matthew Bown | Continue reading }