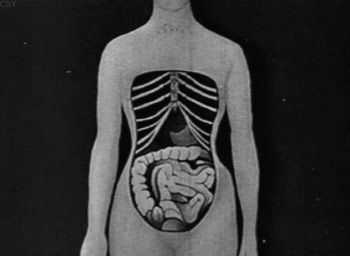

Last fall I had myself tested for 320 chemicals I might have picked up from food, drink, the air I breathe, and the products that touch my skin—my own secret stash of compounds acquired by merely living. It includes older chemicals that I might have been exposed to decades ago, such as DDT and PCBs; pollutants like lead, mercury, and dioxins; newer pesticides and plastic ingredients; and the near-miraculous compounds that lurk just beneath the surface of modern life, making shampoos fragrant, pans nonstick, and fabrics water-resistant and fire-safe.

The tests are too expensive for most individuals—National Geographic paid for mine, which would normally cost around $15,000—and only a few labs have the technical expertise to detect the trace amounts involved. I ran the tests to learn what substances build up in a typical American over a lifetime, and where they might come from. I was also searching for a way to think about risks, benefits, and uncertainty. […]

“In toxicology, dose is everything,” says Karl Rozman, a toxicologist at the University of Kansas Medical Center, “and these doses are too low to be dangerous.” […] Yet even though many health statistics have been improving over the past few decades, a few illnesses are rising mysteriously. From the early 1980s through the late 1990s, autism increased tenfold; from the early 1970s through the mid-1990s, one type of leukemia was up 62 percent, male birth defects doubled, and childhood brain cancer was up 40 percent. Some experts suspect a link to the man-made chemicals that pervade our food, water, and air. There’s little firm evidence. But over the years, one chemical after another that was thought to be harmless turned out otherwise once the facts were in. […]

PCBs, oily liquids or solids, can persist in the environment for decades. In animals, they impair liver function, raise blood lipids, and cause cancers. Some of the 209 different PCBs chemically resemble dioxins and cause other mischief in lab animals: reproductive and nervous system damage, as well as developmental problems. By 1976, the toxicity of PCBs was unmistakable; the United States banned them, and GE stopped using them. But until then, GE legally dumped excess PCBs into the Hudson, which swept them all the way downriver to Poughkeepsie, one of eight cities that draw their drinking water from the Hudson.

In 1984, a 200-mile (300 kilometers) stretch of the Hudson, from Hudson Falls to New York City, was declared a superfund site, and plans to rid the river of PCBs were set in motion. GE has spent 300 million dollars on the cleanup so far. […]

And that faint lavender scent as I shampoo my hair? Credit it to phthalates, molecules that dissolve fragrances, thicken lotions, and add flexibility to PVC, vinyl, and some intravenous tubes in hospitals. The dashboards of most cars are loaded with phthalates, and so is some plastic food wrap. Heat and wear can release phthalate molecules, and humans swallow them or absorb them through the skin. […]

My inventory of household chemicals also includes perfluorinated acids (PFAs)—tough, chemically resistant compounds that go into making nonstick and stain-resistant coatings. 3M also used them in its Scotchgard protector products until it found that the specific PFA compounds in Scotchgard were escaping into the environment and phased them out. In animals these chemicals damage the liver, affect thyroid hormones, and cause birth defects and perhaps cancer, but not much is known about their toxicity in humans. […]

And then there is mercury, a neurotoxin that can permanently impair memory, learning centers, and behavior. Coal-burning power plants are a major source of mercury, sending it out their stacks into the atmosphere, where it disperses in the wind, falls in rain, and eventually washes into lakes, streams, or oceans. There bacteria transform it into a compound called methylmercury, which moves up the food chain after plankton absorb it from the water and are eaten by small fish. Large predatory fish at the top of the marine food chain, like tuna and swordfish, accumulate the highest concentrations of methylmercury—and pass it on to seafood lovers.

I don’t eat much fish, and the levels of mercury in my blood were modest. But I wondered what would happen if I gorged on large fish for a meal or two. So one afternoon I bought some halibut and swordfish at a fish market in the old Ferry Building on San Francisco Bay. Both were caught in the ocean just outside the Golden Gate, where they might have picked up mercury from the old mines. That night I ate the halibut with basil and a dash of soy sauce; I downed the swordfish for breakfast with eggs (cooked in my nonstick pan).

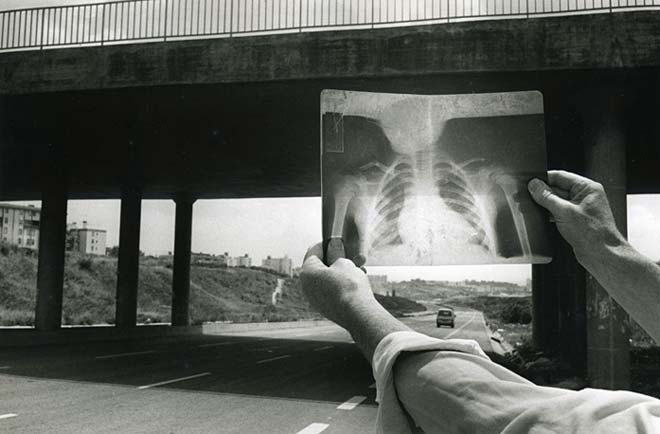

Twenty-four hours later I had my blood drawn and retested. My level of mercury had more than doubled, from 5 micrograms per liter to a higher-than-recommended 12. Mercury at 70 or 80 micrograms per liter is dangerous for adults, says Leo Trasande, and much lower levels can affect children. “Children have suffered losses in IQ at 5.8 micrograms.” He advises me to avoid repeating the gorge experiment.

{ National Geographic | Continue reading | Thanks Tim }