science

When you really focus your attention on something, you’re said to be “in the present moment.” But a new piece of research suggests that the “present moment” is actually […] a sort of composite—a product mostly of what we’re seeing now, but also influenced by what we’ve been seeing for the previous 15 seconds or so. They call this ephemeral boundary the “continuity field.”

{ Quartz | Continue reading }

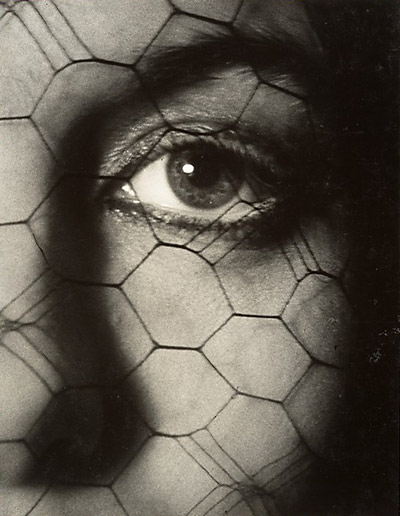

photo { Richard Sandler }

eyes, neurosciences | April 7th, 2014 3:20 pm

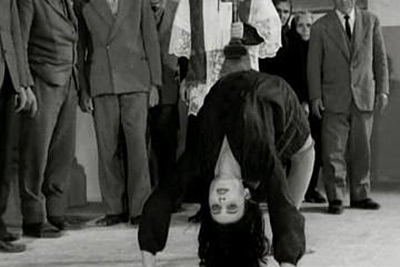

A fascinating paper asks what one man with no memory – and no regrets – can really teach us about time. […]

Researchers Carl Craver and colleagues describe the case of “KC”, a former “roadie for rock bands, prone to drinking and occasional rash behavior” who suffered extensive brain damage in a motorcycle crash. In particular, KC lost his hippocampus on both sides of the brain. This area is crucial for memory, so KC experiences profound amnesia. In fact, he’s one of the best known cases of the condition.

KC is unable to form any new long-term memories: he forgets everything that happens within a matter of minutes. He also, famously, cannot imagine anything happening in either the past or the future. Here’s a much-quoted conversation between him and neuroscientist Endel Tulving.

ET: What will you be doing tomorrow?

[15 second pause.]

KC: I don’t know.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

photo { Archana Rayamajhi }

memory | April 2nd, 2014 1:34 pm

People often believe they have more control over outcomes (particularly positive outcomes) than they actually do. Psychologists discovered this illusion of control in controlled experiments. […] People suffering from depression tend not to fall for this illusion. That fact, along with similar findings from depression, gave rise to the term depressive realism. Two recent studies now suggest that patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) may also represent contingency and estimate personal control differently from the norm. […] Their obsessions cause them distress and they perform compulsions in an effort to regain some sense of control over their thoughts, fears, and anxieties. Yet in some cases, compulsions (like sports fans’ superstitions) seem to indicate an inflated sense of personal control. Based on this conventional model of OCD, you might predict that people with the illness will either underestimate or overestimate their personal control over events. So which did the studies find? In a word: both.

{ Garden of the Mind | Continue reading }

psychology | March 28th, 2014 6:20 am

A recent paper has put a hole in another remnant of Freud’s influence, that suppressed memories are still active. Freud noticed that we can suppress unwelcome memories. He theorized that the suppressed memories continued to exist in the unconscious mind and could unconsciously affect behaviour. Uncovering these memories and their influence was a large part of psychoanalysis. Understanding whether this theory is valid is important for evaluating recovered memories of abuse and for dealing with post-traunatic stress disorder.

The question Gagnepain, Henson and Anderson set out to answer was whether successfully suppressed conscious memories were also suppressed unconsciously or whether they were still unconsciously active. […]

[T]he results do fit with a number of other findings about memory, so that it is now unwise to take the Freudian view of suppression as reliable.

{ Neuro-patch | Continue reading }

memory | March 24th, 2014 1:26 pm

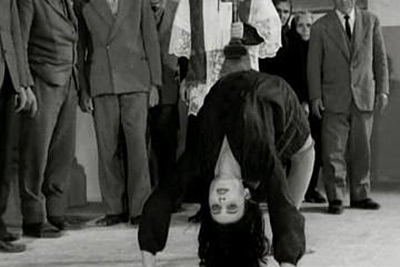

Male movements serve as courtship signals in many animal species, and may honestly reflect the genotypic and/or phenotypic quality of the individual. Attractive human dance moves, particularly those of males, have been reported to show associations with measures of physical strength, prenatal androgenization and symmetry. […]

By using cutting-edge motion-capture technology, we have been able to precisely break down and analyse specific motion patterns in male dancing that seem to influence women’s perceptions of dance quality. We find that the variability and amplitude of movements in the central body regions (head, neck and trunk) and speed of the right knee movements are especially important in signalling dance quality.

{ Biology Letters | PDF }

dance, psychology | March 22nd, 2014 11:01 am

At one end is our everyday consciousness, and at the other is total unconsciousness, as represented by coma. Actually, the term “coma” covers two very similar states: One is the kind of coma that results from a severe head injury or cardiac arrest, and the other is the state induced in a hospital setting by means of general anesthesia.

So anyone who has had general anesthesia has been in a coma?

Yes, general anesthesia is nearly identical to what we might call “natural” coma.

{ American Scientist | Continue reading }

brain, neurosciences | March 22nd, 2014 11:00 am

Your voice betrays your personality in a split second

[…]

They extracted the word “hello” and asked 320 people to rate the voices on a scale of 1 to 9 for one of 10 perceived personality traits – including trustworthiness, dominance and attractiveness. […] “We were surprised by just how similar people’s ratings were.” […] most people agreed very closely to what extent each voice represented each trait.

{ NewScientist | Continue reading }

related { How sound affects the taste of our food }

noise and signals, psychology | March 14th, 2014 12:33 pm

These fictional examples suggest that creativity and dishonesty often go hand-in-hand. Is there an actual link? Is there something about the creative process that triggers unethical behavior? Or does behaving in dishonest ways spur creative thinking? My research suggests that they both exist: Encouraging people to think outside the box can result in greater cheating, and crossing ethical boundaries can make people more creative in subsequent tasks.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology | March 11th, 2014 11:59 am

The arguments for ditching notes and coins are numerous, and quite convincing. In the US, a study by Tufts University concluded that the cost of using cash amounts to around $200 billion per year – about $637 per person. This is primarily the costs associated with collecting, sorting and transporting all that money, but also includes trivial expenses like ATM fees. Incidentally, the study also found that the average American wastes five and a half hours per year withdrawing cash from ATMs; just one of the many inconvenient aspects of hard currency.

While coins last decades, or even centuries, paper currency is much less durable. A dollar bill has an average lifespan of six years, and the US Federal Reserve shreds somewhere in the region of 7,000 tons of defunct banknotes each year.

Physical currency is grossly unhealthy too. Researchers in Ohio spot-checked cash used in a supermarket and found 87% contained harmful bacteria. Only 6% of the bills were deemed “relatively clean.” […]

Stockholm’s homeless population recently began accepting card payments. […]

Cash transactions worldwide rose just 1.75% between 2008 and 2012, to $11.6 trillion. Meanwhile, non traditional payment methods rose almost 14% to total $6.4 trillion.

{ TransferWise | Continue reading }

The anal stage is the second stage in Sigmund Freud’s theory of psychosexual development, lasting from age 18 months to three years. According to Freud, the anus is the primary erogenous zone and pleasure is derived from controlling bladder and bowel movement. […]

The negative reactions from their parents, such as early or harsh toilet training, can lead the child to become an anal-retentive personality. If the parents tried forcing the child to learn to control their bowel movements, the child may react by deliberately holding back in rebellion. They will form into an adult who hates mess, is obsessively tidy, punctual, and respectful to authority. These adults can sometimes be stubborn and be very careful over their money.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

related { Hackers Hit Mt. Gox Exchange’s CEO, Claim To Publish Evidence Of Fraud | Where are the 750k Bitcoins lost by Mt. Gox? }

economics, psychology, theory | March 10th, 2014 8:28 am

Two fields stand out as different within cognitive psychology. These are the study of reasoning, especially deductive reasoning and statistical inference, and the more broadly defined field of decision making. For simplicity I label these topics as the study of reasoning and decision making (RDM). What make RDM different from all other fields of cognitive psychology is that psychologists constantly argued with each other and with philosophers about whether the behavior of their participants is rational. The question I address here is why? What is so different about RDM that it attracts the interests of philosophers and compulsively engages experimental psychologists in judgments of how good or bad is the RDM they observe.

Let us first consider the nature of cognitive psychology in general. It is branch of cognitive science, concerned with the empirical and theoretical study of cognitive processes in humans. It covers a wide collection of processes connected with perception, attention, memory, language, and thinking. However, only in the RDM subset of the psychology of thinking is rationality an issue. For sure, accuracy measures are used throughout cognitive psychology. We can measure whether participants detect faint signals, make accurate judgments of distances, recall words read to them correctly and so on. The study of non-veridical functions is also a part of wider cognitive psychology, for example the study of visual illusions, memory lapses, and cognitive failures in normal people as well as various pathological conditions linked to brain damage, such as aphasia. But in none of these cases are inaccurate responses regarded as irrational. Visual illusions are attributed to normally adaptive cognitive mechanisms that can be tricked under special circumstances; memory errors reflect limited capacity systems and pathological cognition to brain damage or clinical disorders. In no case is the person held responsible and denounced as irrational.

{ Frontiers | Continue reading }

photo { Slim Aarons }

ideas, psychology | March 9th, 2014 4:52 am

“Saying there are differences in male and female brains is just not true. There is pretty compelling evidence that any differences are tiny and are the result of environment not biology,” said Prof Rippon.

“You can’t pick up a brain and say ‘that’s a girls brain, or that’s a boys brain’ in the same way you can with the skeleton. They look the same.” […]

A women’s brain may therefore become ‘wired’ for multi-tasking simply because society expects that of her and so she uses that part of her brain more often. The brain adapts in the same way as a muscle gets larger with extra use.

{ Telegraph | Continue reading }

photo { John Gutmann, Freaky Faces Graffiti (Masks Graffiti), San Francisco, 1939 }

brain, genders, neurosciences | March 9th, 2014 4:48 am

Both men and women erred in estimating what the opposite sex would find attractive. Men thought women would like a heavier stature than females reported they like, and women thought men would like women thinner than men reported they like.

Results suggest that, overall, men’s perceptions serve to keep them satisfied with their figures, whereas women’s perceptions place pressure on them to lose weight.

{ APA/PsycNET | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships | March 7th, 2014 7:48 am

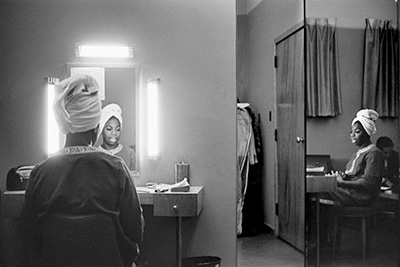

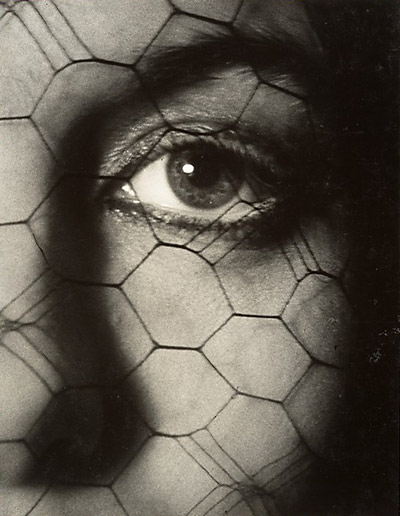

Our brains show more activity in their emotional regions when the music we are listening to is familiar, regardless of whether or not we actually like it.

{ Aeon | Continue reading }

related { Young Musicians Reap Long-Term Neuro Benefits }

and { By Licking These Electric Ice Cream Cones, You Can Make Music }

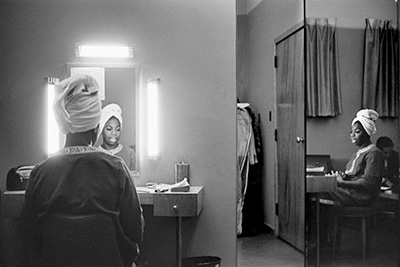

photo { Nina Simone by Alfred Wertheimer, December 1964 }

music, neurosciences | March 7th, 2014 7:48 am

psychology | March 7th, 2014 5:40 am

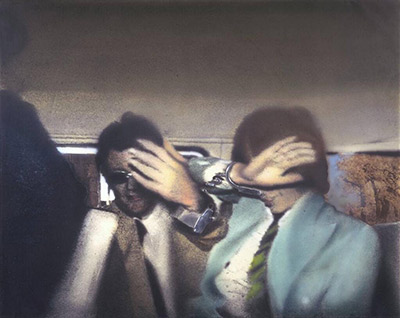

It’s a concept that had become universally understood: humans experience six basic emotions—happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, and surprise—and use the same set of facial movements to express them. What’s more, we can recognize emotions on another’s face, whether that person hails from Boston or Borneo.

The only problem with this concept, according to Northeastern University Distinguished Professor of Psychology Lisa Feldman Barrett, is that it isn’t true at all.

{ Northeastern | Continue reading }

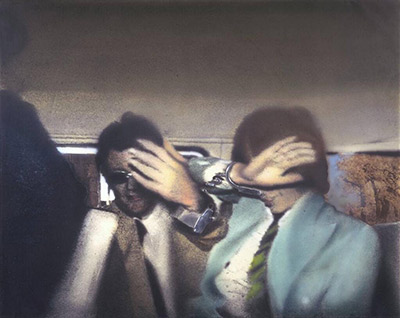

art { Richard Hamilton, Swingeing London 67 (f), 1968-9 | Acrylic paint, screenprint, paper, aluminium and metalised acetate on canvas }

faces, psychology | March 5th, 2014 9:33 am

Quantum physics is famously weird, counterintuitive and hard to understand; there’s just no getting around this. So it is very reassuring that many of the greatest physicists and mathematicians have also struggled with the subject. The legendary quantum physicist Richard Feynman famously said that if someone tells you that they understand quantum mechanics, then you can be sure that they are lying. And Conway too says that he didn’t understand the quantum physics lectures he took during his undergraduate degree at Cambridge.

The key to this confusion is that quantum physics is fundamentally different to any of the previous theories explaining how the physical world works. In the great rush of discoveries of new quantum theory in the 1920s, the most surprising was that quantum physics would never be able to exactly predict what was going to happen. In all previous physical theories, such as Newton’s classical mechanics or Einstein’s theories of special and general relativity, if you knew the current state of the physical system accurately enough, you could predict what would happen next. “Newtonian gravitation has this property,” says Conway. “If I take a ball and I throw it vertically upwards, and I know its mass and I know its velocity (suppose I’m a very good judge of speed!) then from Newton’s theories I know exactly how high it will go. And if it doesn’t do exactly as I expect then that’s because of some slight inaccuracy in my measurements.”

Instead quantum physics only offers probabilistic predictions: it can tell you that your quantum particle will behave in one way with a particular probability, but it could also behave in another way with another particular probability. “Suppose there’s this little particle and you’re going to put it in a magnetic field and it’s going to come out at A or come out at B,” says Conway, imagining an experiment, such as the Stern Gerlach experiment, where a magnetic field diverts an electron’s path. “Even if you knew exactly where the particles were and what the magnetic fields were and so on, you could only predict the probabilities. A particle could go along path A or path B, with perhaps 2/3 probability it will arrive at A and 1/3 at B. And if you don’t believe me then you could repeat the experiment 1000 times and you’ll find that 669 times, say, it will be at A and 331 times it will be at B.”

{ The Free Will Theorem, Part I | Continue reading | Part II | Part III }

Physics, theory | March 4th, 2014 4:26 pm

When a coin falls in water, its trajectory is one of four types determined by its dimensionless moment of inertia I∗ and Reynolds number Re: (A) steady; (B) fluttering; (C) chaotic; or (D) tumbling. The dynamics induced by the interaction of the water with the surface of the coin, however, makes the exact landing site difficult to predict a priori.

Here, we describe a carefully designed experiment in which a coin is dropped repeatedly in water to determine the probability density functions (pdf) associated with the landing positions for each of the four trajectory types, all of which are radially symmetric about the centre drop-line.

{ arXiv | PDF }

Physics, water | March 4th, 2014 10:45 am

Men want sex more than women do. (While I am sure that you can think of people who don’t fit this pattern, my colleagues and I have arrived at this conclusion after reviewing hundreds of findings. It is, on average, a very robust finding.) This difference is due in part to the fact that men, compared to women, focus on the rewards of sex. Women tend to focus on its costs because having sex presents them with bigger potential downsides, from physical (the toll of bearing a child) to social (stigma).

Accordingly, the average man’s sexual system gets activated fairly easily. When it does, it trips off a whole system in the brain focused on rewards. In fact, merely seeing a bra can propel men into reward mode, seeking immediate satisfaction in their decisions.

Most of the evidence suggests that women are different, that a sexy object would not cause them to shift into reward mode. This goes back to the notion that sex is rife with potential costs for women. Yet, at a basic biological level, the sexual system is directly tied to the reward system (through pleasure-giving dopaminergic reactions). This would seem to suggest a contrasting hypothesis that perhaps women will also shift into reward mode when their sexual system is activated. […] Women, more than men, connect sex to emotions. Festjens and colleagues therefore used a subtle, emotional cue to initiate sexual motivation – touch. Across three experiments, Festjens and colleagues found that women who touched sexy male clothing items, compared to nonsexual clothing items, showed evidence of being in reward mode.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

“If a stranger came up to a woman, grabbed her around the waist, and rubbed his groin against her in a university cafeteria or on a subway, she’d probably call the police. In the bar, the woman just tries to get away from him.”

[…]

“The current study was part of an evaluation of the Safer Bars program, a program we developed to reduce aggression in bars, primarily male-to-male aggression,” said Graham. “However, when we saw how much sexual aggression there was, we decided to conduct additional analyses. So these analyses of sexual aggression were in response to how much we observed – which was considerably more than we were expecting.”

{ ScienceNewsline | Continue reading }

photo { John Gutmann, Memory, 1939 }

psychology, relationships, sex-oriented | March 4th, 2014 10:00 am

The simplest type of human communication is non verbal signals: things like posture, facial expression, gestures, tone of voice. They are in effect contagious: if you are sad, I will feel a little sad, if I then cheer up, you may too. The signals are indications of emotional states and we tend to react to another’s emotional state by a sort of mimicry that puts us in sync with them. We can carry on a type of emotional conversation in this way. Music appears to use this emotional communication – it causes emotions in us without any accompanying semantic messages. It appears to cause that contagion with three aspects: the rhythmic rate, the sound envelope and the timbre of the sound. For example a happy musical message has a fairly fast rhythm, flat loudness envelop with sharp ends, lots of pitch variation and a simple timbre with few harmonics. Language seems to use the same system for emotion, or at least some emotion. The same rhythm, sound envelope and timbre is used in the delivery of oral language and it carries the same emotional signals. Whether it is music or language, this sound specification cuts right past the semantic and cognitive processes and goes straight to the emotional ones. Language seems to share these emotional signals with music but not the semantic meaning that language contains.

{ Neuro-patch | Continue reading }

music, neurosciences | March 3rd, 2014 9:18 am

Chefs have been using the sensation of chillies and other peppers to spice up their culinary experiments for centuries. But it is only in the last decade or so that scientists have begun to understand how we taste piquant foods. Now they have found the mechanism that not only explains the heat of chillies and wasabi, but also the soothing cooling of flavours like menthol.

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond cuisine. The same mechanisms build the body’s internal thermometer, and some animals even use them to see in the dark. Understand these pathways, and the humble chilli may open new avenues of research for conditions as diverse as chronic pain, obesity and cancer.

{ NewScientist | Continue reading }

food, drinks, restaurants, science | March 3rd, 2014 6:44 am