science

There is a motif, in fiction and in life, of people having wonderful things happen to them, but still ending up unhappy. We can adapt to anything, it seems—you can get your dream job, marry a wonderful human, finally get 1 million dollars or Twitter followers—eventually we acclimate and find new things to complain about.

If you want to look at it on a micro level, take an average day. You go to work; make some money; eat some food; interact with friends, family or co-workers; go home; and watch some TV. Nothing particularly bad happens, but you still can’t shake a feeling of stress, or worry, or inadequacy, or loneliness.

According to Dr. Rick Hanson, a neuropsychologist, our brains are naturally wired to focus on the negative, which can make us feel stressed and unhappy even though there are a lot of positive things in our lives. True, life can be hard, and legitimately terrible sometimes. Hanson’s book (a sort of self-help manual grounded in research on learning and brain structure) doesn’t suggest that we avoid dwelling on negative experiences altogether—that would be impossible. Instead, he advocates training our brains to appreciate positive experiences when we do have them, by taking the time to focus on them and install them in the brain. […]

The simple idea is that we we all want to have good things inside ourselves: happiness, resilience, love, confidence, and so forth. The question is, how do we actually grow those, in terms of the brain? It’s really important to have positive experiences of these things that we want to grow, and then really help them sink in, because if we don’t help them sink in, they don’t become neural structure very effectively. So what my book’s about is taking the extra 10, 20, 30 seconds to enable everyday experiences to convert to neural structure so that increasingly, you have these strengths with you wherever you go. […]

As our ancestors evolved, they needed to pass on their genes. And day-to-day threats like predators or natural hazards had more urgency and impact for survival. On the other hand, positive experiences like food, shelter, or mating opportunities, those are good, but if you fail to have one of those good experiences today, as an animal, you would have a chance at one tomorrow. But if that animal or early human failed to avoid that predator today, they could literally die as a result.

That’s why the brain today has what scientists call a negativity bias.[…] For example, negative information about someone is more memorable than positive information, which is why negative ads dominate politics. In relationships, studies show that a good, strong relationship needs at least a 5:1 ratio of positive to negative interactions.

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

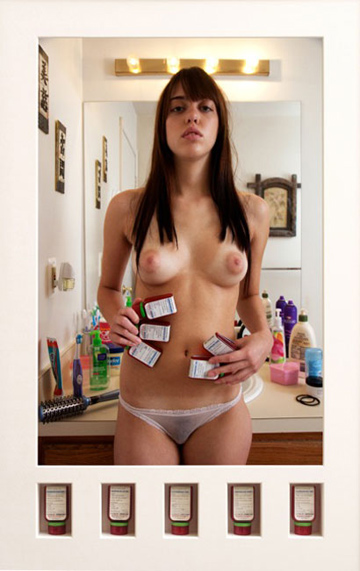

photo and pill bottles { Richard Kern }

brain, guide, psychology | October 25th, 2013 10:27 am

For all the subtlety of its characterization, the book doesn’t just provide a chilling psychological portrait, it conjures up an entire world. The clue is in the name: On some level we’re to imagine that the American Psychiatric Association is a body with real powers, that the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual” is something that might actually be used, and that its caricature of our inner lives could have serious consequences. Sections like those on the personality disorders offer a terrifying glimpse of a futuristic system of repression, one in which deviance isn’t furiously stamped out like it is in Orwell’s unsubtle Oceania, but pathologized instead. Here there’s no need for any rats, and the diagnostician can honestly believe she’s doing the right thing; it’s all in the name of restoring the sick to health. DSM-5 describes a nightmare society in which human beings are individuated, sick, and alone.

{ The New Inquiry | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology | October 23rd, 2013 1:56 pm

Can the experience of an emotion persist once the memory for what induced the emotion has been forgotten? We capitalized on a rare opportunity to study this question directly using a select group of patients with severe amnesia. […]

Our findings provide direct evidence that a feeling of emotion can endure beyond the conscious recollection for the events that initially triggered the emotion.

{ PNAS | Continue reading }

memory | October 22nd, 2013 3:53 pm

Everyone grows older, but scientists don’t really understand why. Now a UCLA study has uncovered a biological clock embedded in our genomes that may shed light on why our bodies age and how we can slow the process. […]

While earlier clocks have been linked to saliva, hormones and telomeres, the new research is the first to identify an internal timepiece able to accurately gauge the age of diverse human organs, tissues and cell types. Unexpectedly, the clock also found that some parts of the anatomy, like a woman’s breast tissue, age faster than the rest of the body.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

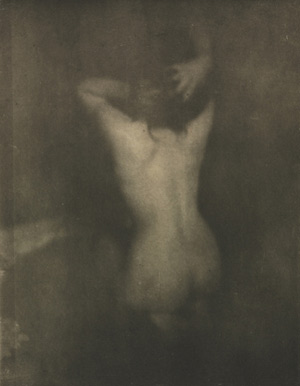

photo { Ray Metzker }

genes, time | October 21st, 2013 1:01 pm

Neurons communicate using electrical signals. They transmit these signals to neighboring cells via special contact points known as synapses. When new information needs processing, the nerve cells can develop new synaptic contacts with their neighboring cells or strengthen existing synapses. To be able to forget, these processes can also be reversed. The brain is consequently in a constant state of reorganization, yet individual neurons need to be prevented from becoming either too active or too inactive. The aim is to keep the level of activity constant, as the long-term overexcitement of neurons can result in damage to the brain.

Too little activity is not good either. “The cells can only re-establish connections with their neighbors when they are ‘awake’, so to speak, that is when they display a minimum level of activity”, explains Mark Hübener, head of the study. The international team of researchers succeeded in demonstrating for the first time that the brain is able to compensate even massive changes in neuronal activity within a period of two days, and can return to an activity level similar to that before the change. […]

In their study, they examined the visual cortex of mice that recently went blind. As expected, but never previously demonstrated, the activity of the neurons in this area of the brain did not fall to zero but to half of the original value. […] After just a few hours, they could clearly observe how the contact points between the affected neurons and their neighboring cells increased in size. When synapses get bigger, they also become stronger and signals are transmitted faster and more effectively. As a result of this synaptic upscaling, the activity of the affected network returned to its starting value after a period of between 24 and 48 hours.

{ Wired Cosmos | Continue reading }

photo { John Swannell }

brain, neurosciences | October 18th, 2013 1:22 pm

Amnesia comes in distinct varieties. In “retrograde amnesia,” a movie staple, victims are unable to retrieve some or all of their past knowledge—Who am I? Why does this woman say that she’s my wife?—but they can accumulate memories for everything that they experience after the onset of the condition. In the less cinematically attractive “anterograde amnesia,” memory of the past is more or less intact, but those who suffer from it can’t lay down new memories; every person encountered every day is met for the first time. In extremely unfortunate cases, retrograde and anterograde amnesia can occur in the same individual, who is then said to suffer from “transient global amnesia,” a condition that is, thankfully, temporary. Amnesias vary in their duration, scope, and originating events: brain injury, stroke, tumors, epilepsy, electroconvulsive therapy, and psychological trauma are common causes, while drug and alcohol use, malnutrition, and chemotherapy may play a part. […]

When you asked Molaison a question, he could retain it long enough to answer; when he was eating French toast, he could remember previous mouthfuls and could see the evidence that he had started eating it. His unimpaired ability to do these sort of things illustrated a distinction, made by William James, between “primary” and “secondary” memory. Primary memory, now generally known as working memory, evidently did not depend upon the structures that Scoville had removed. The domain of working memory is a hybrid of the instantaneous present and of what James referred to as the “just past.” The experienced present has duration; it is not a point but a plateau. For those few seconds of the precisely now and the just past, the present is unarchived, accessible without conscious search. Beyond that, we have to call up the fragments of past presents. The plateau of Molaison’s working memory was between thirty and sixty seconds long—not very different from that of most people—and this was what allowed him to eat a meal, read the newspaper, solve endless crossword puzzles, and carry on a conversation. But nothing that happened on the plateau of working memory stuck, and his past presents laid down no sediments that could be dredged up by any future presents.

{ The New Yorker | Continue reading }

incidents, memory | October 18th, 2013 1:17 pm

Over the past few years various researchers have made systematic attempts to replicate some of the more widely cited priming experiments. Many of these replications have failed. In April, for instance, a paper in PLoS ONE, a journal, reported that nine separate experiments had not managed to reproduce the results of a famous study from 1998 purporting to show that thinking about a professor before taking an intelligence test leads to a higher score than imagining a football hooligan.

The idea that the same experiments always get the same results, no matter who performs them, is one of the cornerstones of science’s claim to objective truth. If a systematic campaign of replication does not lead to the same results, then either the original research is flawed (as the replicators claim) or the replications are (as many of the original researchers on priming contend). Either way, something is awry.

{ The Economist | Continue reading }

buffoons, science | October 18th, 2013 12:23 pm

The prevalence of depression among those with migraine is approximately twice as high as for those without the disease (men: 8.4% vs. 3.4%; women 12.4% vs. 5.7%), according to a new study published by University of Toronto researchers. […]

Consistent with prior research, the prevalence of migraines was much higher in women than men, with one in every seven women, compared to one in every 16 men, reporting that they had migraines.

{ University of Toronto | Continue reading }

Being ostracized or spurned is just like slamming your hand in a door. To the brain, pain is pain, whether it’s social or physical.

{ Bloomberg Businessweek | Continue reading }

photo { Edward Steichen, Dolor, 1903 }

brain, neurosciences | October 18th, 2013 12:22 pm

The explosion in music consumption over the last century has made ‘what you listen to’ an important personality construct – as well as the root of many social and cultural tribes – and, for many people, their self-perception is closely associated with musical preference. We would perhaps be reluctant to admit that our taste in music alters - softens even - as we get older.

Now, a new study suggests that - while our engagement with it may decline - music stays important to us as we get older, but the music we like adapts to the particular ‘life challenges’ we face at different stages of our lives.

It would seem that, unless you die before you get old, your taste in music will probably change to meet social and psychological needs.

One theory put forward by researchers, based on the study, is that we come to music to experiment with identity and define ourselves, and then use it as a social vehicle to establish our group and find a mate, and later as a more solitary expression of our intellect, status and greater emotional understanding.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Olivia Locher }

music, photogs, psychology, time | October 15th, 2013 11:44 am

“Brain training makes you more intelligent.” – WRONG

There are two forms of activity that must be distinguished: working memory capacity and general fluid intelligence. The first one refers to the ability to keep information in mind or easily retrievable, particularly when we are performing various tasks simultaneously. The second implies the ability to do complex reasoning and solve problems. Most brain trainings are only directed at the first one: the working memory capacity. So yes, you can and should use these games or apps to improve your mental capacity of memorizing. But that won’t make you any better at solving math problems.

{ United Academics | Continue reading }

images { Matt Bower }

brain, guide | October 15th, 2013 11:24 am

Shoppers are more likely to buy a product from a different location when a pleasant sound coming from a particular direction draws attention to the item, according to a new study in the Journal of Consumer Research.

“Suppose that you are standing in a supermarket aisle, choosing between two packets of cookies, one placed nearer your right side and the other nearer your left. While you are deciding, you hear an in-store announcement from your left, about store closing hours,” write authors Hao Shen (Chinese University of Hong Kong) and Jaideep Sengupta (Hong Kong University of Science and Technology). “Will this announcement, which is quite irrelevant to the relative merits of the two packets of cookies, influence your decision?”

In the example above, most consumers would choose the cookies on the left because consumers find it easier to visually process a product when it is presented in the same spatial direction as the auditory signal, and people tend to like things they find easy to process.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

economics, noise and signals, psychology | October 15th, 2013 11:22 am

Physics | October 15th, 2013 11:15 am

Cursing, researchers say, is a human universal. Every language, dialect or patois ever studied, whether living or dead, spoken by millions or by a single small tribe, turns out to have its share of forbidden speech, some variant on comedian George Carlin’s famous list of the seven dirty words that are not supposed to be uttered on radio or television. […]

Researchers point out that cursing is often an amalgam of raw, spontaneous feeling and targeted, gimlet-eyed cunning. When one person curses at another, they say, the curser rarely spews obscenities and insults at random, but rather will assess the object of his wrath, and adjust the content of the “uncontrollable” outburst accordingly.

Because cursing calls on the thinking and feeling pathways of the brain in roughly equal measure and with handily assessable fervor, scientists say that by studying the neural circuitry behind it, they are gaining new insights into how the different domains of the brain communicate — and all for the sake of a well-venomed retort. […]

“Studies show that if you’re with a group of close friends, the more relaxed you are, the more you swear,” Burridge said.

{ SF Gate/Natalie Angier | Continue reading }

Linguistics, neurosciences | October 11th, 2013 3:07 pm

When people want to direct the attention of others, they naturally do so by pointing, starting from a very young age. Now, researchers reporting in Current Biology, a Cell Press publication, on October 10 have shown that elephants spontaneously get the gist of human pointing and can use it as a cue for finding food. That’s all the more impressive given that many great apes fail to understand pointing when it’s done for them by human caretakers, the researchers say.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

images { 1 | 2 }

elephants, science | October 10th, 2013 2:38 pm

No one had previously looked specifically at the differing responses in the brain to poetry and prose.

In research published in the Journal of Consciousness Studies, the team found activity in a “reading network” of brain areas which was activated in response to any written material. But they also found that poetry aroused several of the regions in the brain which respond to music. These areas, predominantly on the right side of the brain, had previously been shown as to give rise to the “shivers down the spine” caused by an emotional reaction to music.

{ University of Exeter | Continue reading }

art { Bridget Riley, Arrest 3, 1965 }

music, neurosciences, poetry | October 10th, 2013 11:00 am

psychology, relationships | October 8th, 2013 3:15 pm

There are many theories about why humans cry ranging from the biophysical to the evolutionary. One of the most compelling hypotheses is Jeffrey Kottler’s, discussed at length in his 1996 book The Language of Tears. Kottler believes that humans cry because, unlike every other animal, we take years and years to be able to fend for ourselves. Until that time, we need a behavior that can elicit the sympathetic consideration of our needs from those around us who are more capable (read: adults). We can’t just yell for help though—that would alert predators to helpless prey—so instead, we’ve developed a silent scream: we tear up. […]

In a study published in 2000, Vingerhoets and a team of researchers found that adults, unlike children, rarely cry in public. They wait until they’re in the privacy of their homes—when they are alone or, at most, in the company of one other adult. On the face of it, the “crying-as-communication” hypothesis does not fully hold up, and it certainly doesn’t explain why we cry when we’re alone, or in an airplane surrounded by strangers we have no connection to. […]

In the same 2000 study, Vingerhoet’s team also discovered that, in adults, crying is most likely to follow a few specific antecedents. When asked to choose from a wide range of reasons for recent spells of crying, participants in the study chose “separation” or “rejection” far more often than other options, which included things like “pain and injury” and “criticism.” Also of note is that, of those who answered “rejection,” the most common subcategory selected was “loneliness.”

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

photo { Adrienne Grunwald }

eyes, psychology, water | October 8th, 2013 2:31 pm

When a healthy person watches a smoothly moving object (say, an airplane crossing the sky), she tracks the plane with a smooth, continuous eye movement to match its displacement. This action is called smooth pursuit. But smooth pursuit isn’t smooth for most patients with schizophrenia. Their eyes often fall behind and they make a series of quick, tiny jerks to catch up or even dart ahead of their target. For the better part of a century, this movement pattern would remain a mystery. But in recent decades, scientific discoveries have lead to a better understanding of smooth pursuit eye movements.

{ Garden of the Mind | Continue reading }

eyes, neurosciences | September 30th, 2013 6:57 pm

Animals living in marine environments keep to their schedules with the aid of multiple independent—and, in at least some cases, interacting—internal clocks. […] Multiple clocks—not just the familiar, 24-hour circadian clock—might even be standard operating equipment in animals.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Thomas Prior }

animals, photogs, science, time | September 26th, 2013 8:33 pm

Subjective experience of time is just that—subjective. Even individual people, who can compare notes by talking to one another, cannot know for certain that their own experience coincides with that of others. But an objective measure which probably correlates with subjective experience does exist. It is called the critical flicker-fusion frequency, or CFF, and it is the lowest frequency at which a flickering light appears to be a constant source of illumination. It measures, in other words, how fast an animal’s eyes can refresh an image and thus process information.

For people, the average CFF is 60 hertz (ie, 60 times a second). This is why the refresh-rate on a television screen is usually set at that value. Dogs have a CFF of 80Hz, which is probably why they do not seem to like watching television. To a dog a TV programme looks like a series of rapidly changing stills.

Having the highest possible CFF would carry biological advantages, because it would allow faster reaction to threats and opportunities. Flies, which have a CFF of 250Hz, are notoriously difficult to swat. A rolled up newspaper that seems to a human to be moving rapidly appears to them to be travelling through treacle.

{ The Economist | Continue reading }

photo { Paul Andrews }

animals, neurosciences, time | September 24th, 2013 1:51 pm