Are you a strict t. t.? says Joe. Not taking anything between drinks, says I.

For 40 years, psychologists thought that humans and animals kept time with a biological version of a stopwatch. Somewhere in the brain, a regular series of pulses was being generated. When the brain needed to time some event, a gate opened and the pulses moved into some kind of counting device.

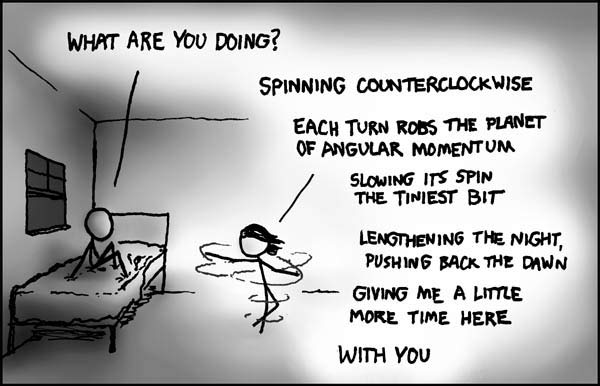

One reason this clock model was so compelling: Psychologists could use it to explain how our perception of time changes. Think about how your feeling of time slows down as you see a car crash on the road ahead, how it speeds up when you’re wheeling around a dance floor in love. Psychologists argued that these experiences tweaked the pulse generator, speeding up the flow of pulses or slowing it down.

But the fact is that the biology of the brain just doesn’t work like the clocks we’re familiar with. Neurons can do a good job of producing a steady series of pulses. They don’t have what it takes to count pulses accurately for seconds or minutes or more. The mistakes we make in telling time also raise doubts about the clock models. If our brains really did work that way, we ought to do a better job of estimating long periods of time than short ones. Any individual pulse from the hypothetical clock would be a little bit slow or fast. Over a short time, the brain would accumulate just a few pulses, and so the error could be significant. The many pulses that pile up over long stretches of time should cancel their errors out. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. As we estimate longer stretches of time, the range of errors gets bigger as well.