‘Nothingness haunts being.’ –Jean-Paul Sartre

It was an invitation-only party (crabs, cocktails and a D.J. on a moonlit dock) thrown by Jane Street, a secretive E.T.F. trading firm that, after years of minting money in the shadows of Wall Street, is now pitching itself to some of the largest institutional investors in the world.

And the message was clear: Jane Street, which barely existed 15 years ago and now trades more than $1 trillion a year, was ready to take on the big boys.

Much of what Jane Street, which occupies two floors of an office building at the southern tip of Manhattan, does is not known. That is by design, as the firm deploys specialized trading strategies to capture arbitrage profits by buying and selling (using its own capital) large amounts of E.T.F. shares.

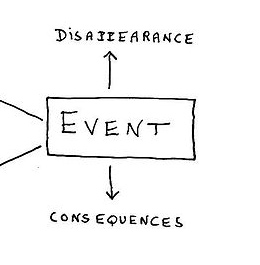

It’s a risky business.

As the popularity of E.T.F.s has soared — exchange-traded funds now account for a third of all publicly traded equities — the spreads, or margins, have narrowed substantially, making it harder to profit from the difference.

And in many cases, some of the most popular E.T.F.s track hard-to-trade securities like junk bonds, emerging-market stocks and a variety of derivative products, adding an extra layer of risk. […]While traders at large investment banks watched their screens in horror, at Jane Street, a bunch of Harvard Ph.D.s wearing flip-flops, shorts and hoodies, swung into action with a wave of buy orders. By the end of the day, the E.T.F. shares had retraced their sharp falls.

It is not only Jane Street, of course. Cantor Fitzgerald, the Knight Capital Group and the Susquehanna International Group have all capitalized on the E.T.F. explosion.

And as these firms have grown, so has the demand for a new breed of Wall Street trader — one who can build financial models and write computer code but who also has the guts to spot a market anomaly and bet big with the firm’s capital. […]

Here is a small sample of Jane Street’s main traders: Tao Wang (doctorate in philosophy and finance from the National University of Singapore), Min Zhu (master’s in chemistry, Columbia), Brett Harrison (master’s in computer science with a focus in artificial intelligence, Harvard) and Srihari Seshadri (bachelor’s in computer science, Carnegie Mellon).

oil on Masonite { Grant Wood, Birthplace of Herbert Hoover, 1931 }